Translation and Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

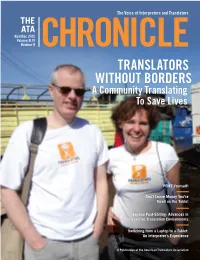

TRANSLATORS WITHOUT BORDERS a Community Translating to Save Lives

The Voice of Interpreters and Translators THE ATA Nov/Dec 2015 Volume XLIV Number 9 CHRONICLE TRANSLATORS WITHOUT BORDERS A Community Translating To Save Lives PEMT Yourself! Don't Leave Money You're Owed on the Table! Beyond Post-Editing: Advances in Interactive Translation Environments Switching from a Laptop to a Tablet: An Interpreter’s Experience A Publication of the American Translators Association CAREERS at the NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY inspiredTHINKING When in the office, NSA language analysts develop new perspectives NSA has a critical need for individuals with the on the dialect and nuance of foreign language, on the context and following language capabilities: cultural overtones of language translation. • Arabic • Chinese We draw our inspiration from our work, our colleagues and our lives. • Farsi During downtime we create music and paintings. We run marathons • Korean and climb mountains, read academic journals and top 10 fiction. • Russian • Spanish Each of us expands our horizons in our own unique way and makes • And other less commonly taught languages connections between things never connected before. APPLY TODAY At the National Security Agency, we are inspired to create, inspired to invent, inspired to protect. U.S. citizenship is required for all applicants. NSA is an Equal Opportunity Employer and abides by applicable employment laws and regulations. All applicants for employment are considered without regard to age, color, disability, genetic information, national origin, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, or status as a parent. Search NSA to Download WHERE INTELLIGENCE GOES TO WORK® 14CNS-10_8.5x11(live_8x10.5).indd 1 9/16/15 10:44 AM Nov/Dec 2015 Volume XLIV CONTENTS Number 9 FEATURES 19 Beyond Post-Editing: Advances in Interactive 9 Translation Environments Translators without Borders: Post-editing was never meant A Community Translating to be the future of machine to Save Lives translation. -

Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain

Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain by Catherine Fleming A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Catherine Fleming 2018 Translation, Reputation, and Authorship in Eighteenth-Century Britain Catherine Fleming Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis explores the reputation-building strategies which shaped eighteenth-century translation practices by examining authors of both translations and original works whose lives and writing span the long eighteenth century. Recent studies in translation have often focused on the way in which adaptation shapes the reception of a foreign work, questioning the assumptions and cultural influences which become visible in the process of transformation. My research adds a new dimension to the emerging scholarship on translation by examining how foreign texts empower their English translators, offering opportunities for authors to establish themselves within a literary community. Translation, adaptation, and revision allow writers to set up advantageous comparisons to other authors, times, and literary milieux and to create a product which benefits from the cachet of foreignness and the authority implied by a pre-existing audience, successful reception history, and the standing of the original author. I argue that John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Eliza Haywood, and Elizabeth Carter integrate this legitimizing process into their conscious attempts at self-fashioning as they work with existing texts to demonstrate creative and compositional skills, establish kinship to canonical authors, and both ii construct and insert themselves within a literary canon, exercising a unique form of control over their contemporary reputation. -

Living Currency, Pierre Klossowski, Translated by Vernon Cisney, Nicolae Morar and Daniel

LIVING CURRENCY ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY How to Be a Marxist in Philosophy, Louis Althusser Philosophy for Non-Philosophers, Louis Althusser Being and Event, Alain Badiou Conditions, Alain Badiou Infinite Thought, Alain Badiou Logics of Worlds, Alain Badiou Theoretical Writings, Alain Badiou Theory of the Subject, Alain Badiou Key Writings, Henri Bergson Lines of Flight, Félix Guattari Principles of Non-Philosophy, Francois Laruelle From Communism to Capitalism, Michel Henry Seeing the Invisible, Michel Henry After Finitude, Quentin Meillassoux Time for Revolution, Antonio Negri The Five Senses, Michel Serres Statues, Michel Serres Rome, Michel Serres Geometry, Michel Serres Leibniz on God and Religion: A Reader, edited by Lloyd Strickland Art and Fear, Paul Virilio Negative Horizon, Paul Virilio Althusser’s Lesson, Jacques Rancière Chronicles of Consensual Times, Jacques Rancière Dissensus, Jacques Rancière The Lost Thread, Jacques Rancière Politics of Aesthetics, Jacques Rancière Félix Ravaisson: Selected Essays, Félix Ravaisson LIVING CURRENCY Followed by SADE AND FOURIER Pierre Klossowski Edited by Vernon W. Cisney, Nicolae Morar and Daniel W. Smith Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Collection first published in English 2017 © Copyright to the collection Bloomsbury Academic, 2017 Vernon W. Cisney, Nicolae Morar, and Daniel W. Smith have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

John Steinbeck in East European Translation

John Steinbeck in East European Translation John Steinbeck in East European Translation: A Bibliographical and Descriptive Overview By Danica Čerče John Steinbeck in East European Translation: A Bibliographical and Descriptive Overview By Danica Čerče This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Danica Čerče All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7324-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7324-6 Cover image by Borut Bončina TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Luchen Li Chapter One ................................................................................................. 5 Steinbeck and East European Publishers Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 21 A Catalogue of Steinbeck Translations in the Languages of Eastern Europe -

The Status of the Translation Profession in the European Union 7/2012

Studies on translation and multilingualism The Status of the Translation Profession in the European Union 7/2012 Translation Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 Manuscript completed in January 2012 ISBN 978-92-79-25021-7 doi:10.2782/63429 © European Union, 2012 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium PRINTED ON CHLORINE-FREE BLEACHED PAPER The status of the translation profession in the European Union (DGT/2011/TST) Final Report 24 July 2012 Anthony Pym, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, European Society for Translation Studies François Grin, Université de Genève Claudio Sfreddo, Haute école spécialisée de Suisse occidentale Andy L. J. Chan, Hong Kong City University TST project site: http://isg.urv.es/publicity/isg/projects/2011_DGT/tst.html Disclaimer: This report has been funded by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Translation. It nevertheless reflects the views of the authors only, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for the nature of use of the information contained herein. 1 2 Executive summary This report is a study of the mechanisms by which the status of translators is signalled in the European Union in 2011-12, with comparisons with the United States, Canada and Australia. -

Propuesta De Didactización De Contenidos De Historia De La Traducción Para La Formación Del Traductor” by Pilar Martino Alba

A PROPOSAL FOR A COURSE ON THE HISTORY OF TRANSLATION FOR A HUMANISTIC TRANSLATOR TRAINING1 Pilar Martino Alba [email protected] Universidad Rey Juan Carlos Susi Herrero Díaz (Translation) Abstract History of Translation should be considered a fundamental issue and one of the founding areas in the formative years of a translator. Within the teaching–learning process, the prospective translator has the opportunity to expand his/her worldview and learn how to handle the tapestry of encyclopedic knowledge which will allow weaving the texts with artistic skills and real craftsmanship. This constitutes the main objective of my proposal. The approach I take here extends beyond the introduction of chronological distribution divided into major historical periods. In each of them, I analyze the historical, sociological and political contexts based on texts and biographies which enable highlighting the real actors of the translation process. Finally, this approach leads toward the analysis and comments on the texts, those being the product of reflections on the translators‟ work. Thus, I propose a circular vision of the History of Translation, starting with a debate on the iconographic symbols which show clearly the translator´s activity and, subsequently, drawing the circle mentioned previously, across the areas of context, actor and text. Resumen La formación humanística inherente al traductor tiene uno de sus pilares en el conocimiento de la historia de la disciplina. En el proceso de enseñanza–aprendizaje, el futuro traductor tiene la oportunidad de ampliar su cosmovisión y aprender a manejar la lanzadera del telar de conocimiento enciclopédico que le permitirá tramar sus textos con artesanal y artística destreza, siendo éste uno de los objetivos de nuestra propuesta. -

Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974 Copyright © 2004 Semiotext(E) All Rights Reserved

Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974 Copyright © 2004 Semiotext(e) All rights reserved. © 2002 Les editions de Minuit, 7, rue Bernard-Palissy, 75006 Paris. Semiotext(e) 2571 W. Fifth Street 501 Philosophy Hall Los Angeles, CA 90057 Columbia University www.semiotexte.org New York, NY 10027 Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England Special thanks to fellow translators in this volume: Christopher Bush, Charles Stivale and Melissa McMahon, Alexander Hickox, Teal Eich. Other translations are indebted to David L. Sweet, Jarred Baker, and Jeanine Herman's versions previously published in Felix Guattari's Chaosophy (NewYork: Semiotext(e), 1995). Lysa Hochroth's first translations of Deleuze's articles on Hume, Kant, and Bergson, subsequently reviewed by Elie During, were also invaluable. Special thanks to Giancarlo Ambrosino, Eric Eich, Teal Eich, Ames Hodges, Patricia Ferrell, Janet Metcalfe for their close reading and suggestions. The Index was established by Giancarlo Ambrosino. Cover Photo: Jean-Jacques Lebel. © Jean-Jacques Lebel archive, Paris Design: Hedi El Kholti ISBN: 1-58435-018-0 Printed in the United States of America Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974 Gilles Deleuze Edited by David Lapoujade Translated by Michael Taormina SEMIOTEXT(E) FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES Contents 7 Introduction 9 Desert Islands 15 Jean Hyppolite's Logic and Existence 19 Instincts and Institutions 22 Bergson, 1859-1941 32 Bersson's Conception of Difference 52 Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Precursor of Kafka, Celine, and Ponse 56 The Idea -

Dethroning Dante Skopostheorie in Action

Dethroning Dante Skopostheorie in Action Tim N. Smith Thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Literary Translation Studies 2016 3 4 Quel sorriso m’ha salvato da pianti e da dolori… 5 6 Table of Contents Abstract iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations in the Present Work vi CHAPTER 1 1 Introduction CHAPTER 2 7 Skopostheorie and Its Critics 2.1 An Introduction to Skopostheorie 7 2.2 A Note on ‘Rival’ Theories 15 2.3 Criticisms and Responses 18 2.3.1 Basic Criticisms 19 2.3.2 Ethics 20 2.3.3 Is Skopostheorie Descriptive or Prescriptive? 24 2.3.4 Skopostheorie and Literary Translation 28 2.3.5 How to Spot a Skopos 32 2.3.6 Translation Quality Assessment 34 2.4 Afterword 39 CHAPTER 3 40 Recent Translations of the Inferno: A Functionalist Analysis 3.1 Towards a Practical Retrospective Application for Skopostheorie 40 3.2 Why Skopostheorie Matters 43 3.3 Trends in Translating Dante: In Search of the “Spirit” of the Original 48 3.4 Three Translations of Inferno I 52 3.4.1 Dante Astray: Seamus Heaney’s Poem–Translation (1993) 52 3.4.2 Steve Ellis: Abbreviation and Familiarization (1994) 63 3.4.3 Robert M. Durling: Understanding the Muse or the Philosopher? 70 (1996) 3.5 Some Concluding Remarks on Translations of Dante 79 CHAPTER 4 83 Conclusion Appendix 90 Table of Translators 90 Graph: Mean translations per year 98 Inferno I: A prose translation by Tim N. -

Proceedings of the XVII World Congress International Federation of Translators

FIT 2005 Congres Mondial World Congress Proceedings of the XVII World Congress International Federation of Translators Aetes du XVI ,e Congres mondial Federation Internationale des Tradueteurs Edited by / Edites par Leena Salmi & Kaisa Koskinen D Hosted by the Finnish Association of Translators and Interpreters U Accueilli par l'Association finlandaise des tradudeurs et interpretes Proceedings of the XVII World Congress International Federation of Translators Actes du XVlle Congres mondial Federation Internationale des Traducteurs Tampere, Finland, 4-7 August 2005 Tampere, Finlande, du 4 au 7 aout 2005 Published by / Editeur : International Federation of Translators - Federation Internationale des Traducteurs (FIT) Paris, France Editorial Board / Comite de redaction: Lea Heinonen-Eerola Sheryl Hinkkanen Kaisa Koskinen Leena Salmi Layout / Mise en page : Piia Keljo Tmi, Tampere Printed by / Imprimeur : Offset Ulonen Oy, Tampere Copyright © FIT 2005 All rights reserved. Tous droits reserves. No editorial Intervention was undertaken unless absolutely necessary. The Editorial Board's task was to solicit contributions, to arrange them thematically, and to format them according to the Proceedings style guidelines. The Editorial Board cannot be held liable in any manner for any editorial intervention or for any errors, omissions. or additions to the papers published herein. Le mandat du Comite de redaction a consiste it solliciter des communications, it les organiser selon une logique thematique et it formater leur mise en page selon les regles enoncees dans les directives concernant les Actes. Le Comite de redaction ne saurait etre tenu responsable d'aucune intervention d'ordre redactionnel ni d'aucune erreur, omission ou addition aux communications publiees dans les presents Actes. -

A Guide to Translation Project Management

A Guide to Translation Project Management David Russi – UCAR/COMET Rebecca Schneider – Meteorological Service of Canada Published by The COMET® Program with support from NOAA’s National Weather Service International Activities Office and the Meteorological Service of Canada Version 1.0 ©Copyright 2016 The COMET® Program All Rights Reserved Legal Notice: https://www.meted.ucar.edu/about_legal_es.php Preface This Guide to Translation Project Management provides a set of written guidelines meant to assist organizations around the world wishing to produce quality translations. Although it was designed primarily as a resource for National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) interested in translating instructional materials to support their training and professional development efforts, the general concepts are relevant to any agency or organization desiring to distribute information in other languages. Translation is a complex endeavor, requiring the active collaboration of multiple participants in order to produce a quality product. This guide explains the process involved, describes some possible pitfalls and ways to avoid them, and offers guidance in creating a translation team, including the selection of a translation company or independent translators. It also touches on aspects such as translation and distribution formats, rates, tools, resources, and best practices that can contribute to a good outcome. Finally, the guide includes sample checklists, guidelines and instruction sheets that can be customized for use in various stages of the translation process. This guide was developed as a collaboration project by The COMET Program and the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC). Many thanks to Corinne McKay for her many excellent suggestions, and to Bruce Muller, for editing. -

Slavfile Winter 2011

Spring 2011 Vol. 20, No. 2 SLAVIC LANGUAGES DIVISION AMERICAN TRANSLATORS ASSOCIATION SlavFileSlavFile www.ata-divisions.org/SLD/slavfile.htm 2010 ATA CONFERENCE PRESENTATION REVIEW CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAN: Enhanced Vocabulary, Endangered Syntax Presented by Elizabeth Macheret Reviewed by Galina Palyvian In a presentation entitled “Contemporary Russian: En- A number of words used in the hanced Vocabulary, Endangered Syntax,” Elizabeth Mach- past are now coming back to life eret addressed important topics such as recent changes in without semantic change (e.g., Reviewer Galina Palyvian the modern Russian language on the semantic, morphologi- визитная карточка [visiting/ cal, and syntactic levels. The examples were taken from the business card], биржа [stock market]). In addition, forgot- actual work of professional translators, grant applications ten words are now acquiring new semantic content (e.g., written by Russian college students (majoring in linguistics визитка [short for visiting/business card, instead of the and foreign languages), and from Internet sources. meaning of cutaway coat – a men’s clothing item used in th th Elizabeth started off by quoting three lines from Eugene the 19 and early 20 centuries for morning visits]). Onegin by Alexander Pushkin, which nowadays are often An especially interesting section of the presentation used to excuse one’s linguistic errors: “Как уст румяных included examples of the influence of slang and vernacu- без улыбки, / Без грамматической ошибки / Я русской lar on the development of Russian vocabulary, e.g.: речи не люблю” [“Like rosy lips severe, unsmiling, / To me • знаковый – this was introduced as a semiotic term no Russian sounds beguiling, / Without a grammar gaffe meaning related to signs or symbols, e.g., знаковые or two.” LRS]. -

Hybridity As Epistemology in the Work of Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, and in the Rhetorical Legacy of The

FROM ATHENS (VIA ALEXANDRIA) TO BAGHDAD: HYBRIDITY AS EPISTEMOLOGY IN THE WORK OF AL- KINDI, AL-FARABI, AND IN THE RHETORICAL LEGACY OF THE MEDIEVAL ARABIC TRANSLATION MOVEMENT Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Baddar, Maha Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 14:23:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196136 1 FROM ATHENS (VIA ALEXANDRIA) TO BAGHDAD: HYBRIDITY AS EPISTEMOLOGY IN THE WORK OF AL-KINDI, AL-FARABI, AND IN THE RHETORICAL LEGACY OF THE MEDIEVAL ARABIC TRANSLATION MOVEMENT By Maha Baddar ________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY With A Major IN RHETORIC, COMPOSITION, AND THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Maha Baddar entitled From Athens (via Alexandria) to Baghdad: Hybridity as Epistemology in the Work of Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, and in the Rhetorical Legacy of the Medieval Arabic Translation Movement and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling