Opioid Use Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

What Are the Treatments for Heroin Addiction?

How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse? See page 3. from the director: Research Report Series Heroin is a highly addictive opioid drug, and its use has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug use—such as hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments—have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year. Although heroin use in the general population is rather low, the numbers of people starting to use heroin have been steadily rising since 2007.1 This may be due in part to a shift from abuse of prescription pain relievers to heroin as a readily available, cheaper alternative2-5 and the misperception that highly pure heroin is safer than less pure forms because it does not need to be injected. Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Medications HEROIN are available to treat heroin addiction while reducing drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms, improving the odds of achieving abstinence. There are now a variety of medications that can be tailored to a person’s recovery needs while taking into account co-occurring What is heroin and health conditions. Medication combined with behavioral therapy is particularly how is it used? effective, offering hope to individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. eroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to Hof poppy plants. -

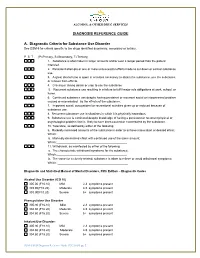

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

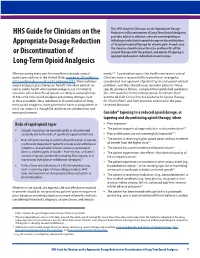

HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage Reduction Or

This HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Analgesics provides advice to clinicians who are contemplating or initiating a reduction in opioid dosage or discontinuation Appropriate Dosage Reduction of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. In each case the clinician should review the risks and benefits of the or Discontinuation of current therapy with the patient, and decide if tapering is appropriate based on individual circumstances. Long-Term Opioid Analgesics After increasing every year for more than a decade, annual needs.2,3,4 Coordination across the health care team is critical. opioid prescriptions in the United States peaked at 255 million in Clinicians have a responsibility to provide or arrange for 2012 and then decreased to 191 million in 2017.i More judicious coordinated management of patients’ pain and opioid-related opioid analgesic prescribing can benefit individual patients as problems, and they should never abandon patients.2 More well as public health when opioid analgesic use is limited to specific guidance follows, compiled from published guidelines situations where benefits of opioids are likely to outweigh risks. (the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain2 At the same time opioid analgesic prescribing changes, such and the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy as dose escalation, dose reduction or discontinuation of long- for Chronic Pain3) and from practices endorsed in the peer- term opioid analgesics, have potential to harm or put patients at reviewed literature. risk if not made in a thoughtful, deliberative, collaborative, and measured manner. -

Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit: Opioid Use Disorder Facts

SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention TOOLKIT Opioid Use Disorder Facts TABLE OF CONTENTS SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit Opioid Use Disorder Facts .................................................................................................................. 1 Scope of the Problem....................................................................................................................... 1 Strategies to Prevent Overdose Deaths ........................................................................................... 2 Resources for Communities ............................................................................................................. 4 References ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... 6 ii OPIOID USE DISORDER FACTS individuals who use opioids and combine SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM them with benzodiazepines, other pioid overdose continues to be a major public health sedative hypnotic agents, or alcohol, all of 2 problem in the United States. It has contributed which cause respiratory depression. significantly to overdose deaths among those who WHO IS AT RISK? Anyone who uses Ouse or misuse illicit and prescription opioids. In fact, all U.S. opioids for long-term management of overdose deaths involving opioids (i.e., unintentional, chronic pain is at risk for opioid -

Screening for Illicit Drug Use, Including Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs: an Updated Systematic Review for the U.S

Evidence Synthesis Number 186 Screening for Illicit Drug Use, Including Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs: An Updated Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. HHSA-290-2015-00007-I-EPC5, Task Order No. 2 Prepared by: Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Portland, OR Investigators: Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, MPH Leslie A. Perdue, MPH Megan Rushkin, MPH Elizabeth A. O’Connor, PhD AHRQ Publication No. 19-05255-EF-1 August 2019 This report is based on research conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. HHSA-290-2015-00007-I). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents, and do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for the application of clinical judgment. Anyone who makes decisions concerning the provision of clinical care should consider this report in the same way as any medical reference and in conjunction with all other pertinent information, i.e., in the context of available resources and circumstances presented by individual patients. -

Ketamine Blocks Morphine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.22.915728; this version posted April 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Ketamine blocks morphine-induced conditioned place preference and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Authors: Greer McKendrick1,3, Hannah Garrett3,6, Holly E. Jones2,3,6, Dillon S. McDevitt2,3, Sonakshi Sharma3, Yuval Silberman4, Nicholas M. Graziane5* Author Affiliations: 1 Neuroscience graduate program, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA 2 Summer Undergraduate Research Internship Program, Penn State College of Medicine 3Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA 4Department of Neural and Behavioral Sciences, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA 5Departments of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine and Pharmacology, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA 6These authors contributed equally: Hannah Garrett and Holly E. Jones. * Correspondence: Nicholas Graziane, Ph.D. E-mail: [email protected] Address: Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Mail Code H187 Pennsylvania State College of Medicine 500 University Drive Hershey, PA 17033 Telephone: 717-531-0003 X-329159 Fax: 717-531-6221 Running title: Ketamine effects on morphine-induced CPP bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.22.915728; this version posted April 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Congress of the United States House of Representatives

FRED UPTON, MICHIGAN FRANK PALLONE, JR., NEW JERSEY CHAIRMAN RANKING MEMBER ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS Congress of the United States House of Representatives COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE 2125 RAYBURN HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING WASHINGTON, DC 20515-6115 Majority (202) 225-2927 Minority (202) 225-3641 MEMORANDUM April 19, 2016 To: Subcommittee on Health Democratic Members and Staff Fr: Committee on Energy and Commerce Democratic Staff Re: Subcommittee on Health Markup of Twelve Opioid Bills On Wednesday, April 20, 2016, the Subcommittee on Health will convene at 1:30 p.m. in room 2322 of the Rayburn House Office Building to hold a markup of the following twelve bills: H.R. 4641, a bill to provide for the establishment of an inter-agency task force to review, modify, and update best practices for pain management and prescribing pain medication; H.R. 3250, the DXM Abuse Prevention Act of 2015; H.R. 3680, the Co-Prescribing to Reduce Overdose Act of 2015; H.R. 3691, the Improving Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women Act of 2015; H.R. __, the Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Expansion and Modernization Act; H.R. 1818, the Veteran Emergency Medical Technician Support Act of 2015; GAO Study on Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome; H.R. 4599, the Reducing Unused Medications Act of 2016; H.R. 4976, the Opioid Review Modernization Act; H.R. 4586, a bill to provide for a grant program to develop standing orders for naloxone prescriptions; H.R. 4969, a bill to direct the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to provide informational materials to educate and prevent addiction in teenagers and adolescents who are injured playing youth sports and subsequently prescribed an opioid; and H.R. -

National Judicial Opioid Task Force Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder

National Judicial Opioid Task Force Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder This document is designed to further educate justice system professionals about Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) and call attention to key issues surrounding medication assisted treatment (MAT), the evidence that underlies treatment types, best practices, and legal implications. Medication Assisted Treatment: Evidence-Based and Best Practices Drug or alcohol use disorders result in long-term No scientific basis exists for concluding that any one physiological changes to regions of the brain that medication is superior to another in reducing influence motivation, decision-making, and behavior, unauthorized opioid use. One exception is that particularly around using or seeking drugs. Cessation of buprenorphine is superior to methadone for use by drug use alone does not return the brain to normal and pregnant women, as fetal outcomes are better. relapses are to be expected. Naltrexone has not been studied, and therefore is not recommended for use by pregnant women or women Medication assisted treatment (MAT) combines the use of who are expecting to become pregnant. counseling and behavioral therapies with Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications to treat Referrals for treatment services are routinely ordered by opioid use disorder (OUD). Under federal law, persons courts. Those who receive both medications and therapy receiving medications for OUD must also be offered are receiving MAT (MAT = Medication + Therapy). counseling (though they are not required to accept it). Medication use in conjunction with behavioral health therapy is optimal; however, research suggests that the Methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone have been medications are the more effective aspect of the associated with significantly reduced use of unauthorized treatment. -

Use of Naloxone for the Prevention of Opioid Overdose Deaths

Public Policy Statement on the Use of Naloxone for the Prevention of Opioid Overdose Deaths Background Drug-related overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the US. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 70,630 drug-related overdose deaths in 2019. Deaths from opioid overdose accounted for 70.6% of those fatalities.1 Provisional estimates indicate that more than 93,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States in the 12-months ending in December 2020, with synthetic opioids as the primary driver for the increase over the period.2,3 Naloxone is a mu-opioid antagonist with well-established safety and efficacy that can reverse opioid-related respiratory arrest and prevent fatalities. Naloxone treatment of opioid overdose has been in use in hospital settings for decades. Over the last several years and in response to the overdose epidemic in the US, training and distribution of naloxone has been expanded to include emergency medical technicians, police officers, firefighters, correctional officers, and others who might experience or witness opioid overdose such as individuals who use opioids and their families.4 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) supports the use of naloxone for the treatment of opioid overdose by bystanders in their Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit.5 Naloxone is a remarkably effective, inexpensive and safe medication. It acts quickly, has no addictive potential, may be dispensed by injection (preferably intramuscular) or intranasally, and has mild side effects (other than precipitating opioid withdrawal) when used at the lowest effective dosage for reversal. -

DSM 5 Diagnostic Codes Related to Substance Use Disorders Published on Buppractice (

DSM 5 Diagnostic Codes Related to Substance Use Disorders Published on BupPractice (http://www.buppractice.com) DSM 5 Diagnostic Codes Related to Substance Use Disorders [1] Description: DSM-IV and DSM 5 Diagnostic Codes Related to Substance Use Disorders (*Note: DSM 5 was released in May 2013 and includes significant changes to diagnosis. For example, it does away with separate "dependence" and "abuse" diagnoses and combines them into "substance use disorder.") The ICD-10 compliance date is October 1, 2015. This is a table listing the diagnostic codes for substance use disorders. DSM-IV Diagnostic DSM-5 Diagnostic Codes (ICD-10-CM) Substance Use Codes (ICD-9-CM) Disorder 303.00 F10.129 Alcohol Intoxication F10.229 F10.929 (Selected code depends on presence and severity of comorbid alcohol use disorder) 305.00 - Alcohol F10.10 Alcohol Use Disorder Abuse F10.20 303.90 - Alcohol Dependence (Selected code depends on number of symptoms present) 304.00 - Opioid F11.10 Opioid Use Disorder Dependence F11.20 305.50 - Opioid Abuse (Selected code depends on number of symptoms present) 292.89 For opioid intoxication without perceptual Opioid Intoxication disturbances: F11.129 (with comorbid mild opioid use disorder) F11.229 (with comorbid moderate or severe opioid use disorder) F11.929 (with no comorbid opioid use disorder) Page 1 of 3 DSM 5 Diagnostic Codes Related to Substance Use Disorders Published on BupPractice (http://www.buppractice.com) For opioid intoxication with perceptual disturbances: F11.122 (with comorbid mild opioid use disorder) -

Committee's Conclusions

CONCLUSIONS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES COMMITTEE 1. Opioid use disorder is a treatable chronic brain disease. Opioid use disorder is a treatable chronic brain disease resulting from the changes in neural structure and function that are caused over time by repeated opioid use. The behavioral and social contexts are critically important both to its development and treatment. Stopping opioid misuse is extremely difficult. Medications are intended to normalize brain structure and function. 2. FDA-approved medications to treat opioid use disorder are effective and save lives. FDA-approved medications to treat opioid use disorder—methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release naltrexone—are effective and save lives. The most appropriate medication varies by individual and may change over time. To stem the opioid crisis, it is critical for all FDA-approved options to be available for all people with opioid use disorder. At the same time, as with all medical disorders, continued research on new medications, approaches, and formulations that will expand the options for patients is needed. 3. Long-term retention on medication for opioid use disorder is associated with improved outcomes. There is evidence that retention on medication for the long term is associated with improved outcomes and that discontinuing medication often leads to relapse and overdose. There is insufficient evidence regarding how the medications compare over the long term. 4. A lack of availability or utilization of behavioral interventions is not a sufficient justification to withhold medications to treat opioid use disorder. Behavioral interventions, in addition to medical management, do not appear to be necessary as treatment in all cases.