Benzodiazepine Taper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal Abstract

Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care CLINICAL REPORT Neonatal Drug Withdrawal Mark L. Hudak, MD, Rosemarie C. Tan, MD,, PhD, THE abstract COMMITTEE ON DRUGS, and THE COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND Maternal use of certain drugs during pregnancy can result in transient NEWBORN neonatal signs consistent with withdrawal or acute toxicity or cause KEY WORDS opioid, methadone, heroin, fentanyl, benzodiazepine, cocaine, sustained signs consistent with a lasting drug effect. In addition, hos- methamphetamine, SSRI, drug withdrawal, neonate, abstinence pitalized infants who are treated with opioids or benzodiazepines to syndrome provide analgesia or sedation may be at risk for manifesting signs ABBREVIATIONS of withdrawal. This statement updates information about the clinical CNS—central nervous system — presentation of infants exposed to intrauterine drugs and the thera- DTO diluted tincture of opium ECMO—extracorporeal membrane oxygenation peutic options for treatment of withdrawal and is expanded to include FDA—Food and Drug Administration evidence-based approaches to the management of the hospitalized in- 5-HIAA—5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid fant who requires weaning from analgesics or sedatives. Pediatrics ICD-9—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision — – NAS neonatal abstinence syndrome 2012;129:e540 e560 SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor INTRODUCTION This document is copyrighted and is property of the American fi Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors Use and abuse of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco contribute signi cantly have filed conflict of interest statements with the American to the health burden of society. The 2009 National Survey on Drug Use Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through and Health reported that recent (within the past month) use of illicit a process approved by the Board of Directors. -

Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW

Guideline Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW Summary To provide the most up-to-date knowledge and current level of best practice for the treatment of withdrawal from alcohol and other drugs such as heroin, and other opioids, benzodiazepines, cannabis and psychostimulants. Document type Guideline Document number GL2008_011 Publication date 04 July 2008 Author branch Centre for Alcohol and Other Drugs Branch contact (02) 9424 5938 Review date 18 April 2018 Policy manual Not applicable File number 04/2766 Previous reference N/A Status Active Functional group Clinical/Patient Services - Pharmaceutical, Medical Treatment Population Health - Pharmaceutical Applies to Area Health Services/Chief Executive Governed Statutory Health Corporation, Board Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Affiliated Health Organisations, Affiliated Health Organisations - Declared Distributed to Public Health System, Ministry of Health, Public Hospitals Audience All groups of health care workers;particularly prescribers of opioid treatments Secretary, NSW Health Guideline Ministry of Health, NSW 73 Miller Street North Sydney NSW 2060 Locked Mail Bag 961 North Sydney NSW 2059 Telephone (02) 9391 9000 Fax (02) 9391 9101 http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/ space space Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Clinical Practice Guidelines - NSW space Document Number GL2008_011 Publication date 04-Jul-2008 Functional Sub group Clinical/ Patient Services - Pharmaceutical Clinical/ Patient Services - Medical Treatment Population Health - Pharmaceutical -

Substance Abuse and Dependence

9 Substance Abuse and Dependence CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE CLASSIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE-RELATED THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 310–316 Residential Approaches DISORDERS 291–296 Biological Perspectives Psychodynamic Approaches Substance Abuse and Dependence Learning Perspectives Behavioral Approaches Addiction and Other Forms of Compulsive Cognitive Perspectives Relapse-Prevention Training Behavior Psychodynamic Perspectives SUMMING UP 325–326 Racial and Ethnic Differences in Substance Sociocultural Perspectives Use Disorders TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Pathways to Drug Dependence AND DEPENDENCE 316–325 DRUGS OF ABUSE 296–310 Biological Approaches Depressants Culturally Sensitive Treatment Stimulants of Alcoholism Hallucinogens Nonprofessional Support Groups TRUTH or FICTION T❑ F❑ Heroin accounts for more deaths “Nothing and Nobody Comes Before than any other drug. (p. 291) T❑ F❑ You cannot be psychologically My Coke” dependent on a drug without also being She had just caught me with cocaine again after I had managed to convince her that physically dependent on it. (p. 295) I hadn’t used in over a month. Of course I had been tooting (snorting) almost every T❑ F❑ More teenagers and young adults die day, but I had managed to cover my tracks a little better than usual. So she said to from alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents me that I was going to have to make a choice—either cocaine or her. Before she than from any other cause. (p. 297) finished the sentence, I knew what was coming, so I told her to think carefully about what she was going to say. It was clear to me that there wasn’t a choice. I love my T❑ F❑ It is safe to let someone who has wife, but I’m not going to choose anything over cocaine. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

International Standards for the Treatment of Drug Use Disorders

"*+,-.*--- -!"#$%&-'",()0"ÿ23 45 "6789!"7(@&A($!7,0B"67$!C#+D"%"*+,9779C&B"!7%EE F33"*+,-.*--- -!"#$%&-'",()0" International standards for the treatment of drug use disorders REVISED EDITION INCORPORATING RESULTS OF FIELD-TESTING International standards for the treatment of drug use disorders: revised edition incorporating results of field-testing ISBN 978-92-4-000219-7 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-000220-3 (print version) © World Health Organization and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO or UNODC endorses any specific organization, products or services. The unauthorized use of the WHO or UNODC names or logos is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO) or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Neither WHO nor UNODC are responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the license shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization F10 - F19 Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use Overview of this block F10. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol F11. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of opioids F12. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cannabinoids F13. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of sedative hypnotics F14. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of cocaine F15. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other stimulants, including caffeine F16. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of hallucinogens F17. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of tobacco F18. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of volatile solvents F19. – Mental and behavioural disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances Four- and five-character codes may be used to specify the clinical conditions, as follows: F1x.0 Acute intoxication .00 Uncomplicated .01 With trauma or other bodily injury .02 With other medical complications .03 With delirium .04 With perceptual distortions .05 With coma .06 With convulsions .07 Pathological intoxication F1x.1 Harmful use F1x.2 Dependence syndrome .20 Currently abstinent .21 Currently abstinent, but in a protected environment .22 Currently on a clinically supervised maintenance or replacement regime [controlled dependence] .23 Currently abstinent, but receiving treatment with -

What Are the Treatments for Heroin Addiction?

How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse? See page 3. from the director: Research Report Series Heroin is a highly addictive opioid drug, and its use has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug use—such as hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments—have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year. Although heroin use in the general population is rather low, the numbers of people starting to use heroin have been steadily rising since 2007.1 This may be due in part to a shift from abuse of prescription pain relievers to heroin as a readily available, cheaper alternative2-5 and the misperception that highly pure heroin is safer than less pure forms because it does not need to be injected. Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Medications HEROIN are available to treat heroin addiction while reducing drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms, improving the odds of achieving abstinence. There are now a variety of medications that can be tailored to a person’s recovery needs while taking into account co-occurring What is heroin and health conditions. Medication combined with behavioral therapy is particularly how is it used? effective, offering hope to individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. eroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to Hof poppy plants. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

DEMAND REDUCTION a Glossary of Terms

UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.00.XI.9 ISBN: 92-1-148129-5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was prepared by the: United Nations International Drug Control Programme (UNDCP), Vienna, Austria, in consultation with the Commonwealth of Health and Aged Care, Australia, and the informal international reference group. ii Contents Page Foreword . xi Demand reduction: A glossary of terms . 1 Abstinence . 1 Abuse . 1 Abuse liability . 2 Action research . 2 Addiction, addict . 2 Administration (method of) . 3 Adverse drug reaction . 4 Advice services . 4 Advocacy . 4 Agonist . 4 AIDS . 5 Al-Anon . 5 Alcohol . 5 Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) . 6 Alternatives to drug use . 6 Amfetamine . 6 Amotivational syndrome . 6 Amphetamine . 6 Amyl nitrate . 8 Analgesic . 8 iii Page Antagonist . 8 Anti-anxiety drug . 8 Antidepressant . 8 Backloading . 9 Bad trip . 9 Barbiturate . 9 Benzodiazepine . 10 Blood-borne virus . 10 Brief intervention . 11 Buprenorphine . 11 Caffeine . 12 Cannabis . 12 Chasing . 13 Cocaine . 13 Coca leaves . 14 Coca paste . 14 Cold turkey . 14 Community empowerment . 15 Co-morbidity . 15 Comprehensive Multidisciplinary Outline of Future Activities in Drug Abuse Control (CMO) . 15 Controlled substance . 15 Counselling and psychotherapy . 16 Court diversion . 16 Crash . 16 Cross-dependence . 17 Cross-tolerance . 17 Custody diversion . 17 Dance drug . 18 Decriminalization or depenalization . 18 Demand . 18 iv Page Demand reduction . 19 Dependence, dependence syndrome . 19 Dependence liability . 20 Depressant . 20 Designer drug . 20 Detoxification . 20 Diacetylmorphine/Diamorphine . 21 Diuretic . 21 Drug . 21 Drug abuse . 22 Drug abuse-related harm . 22 Drug abuse-related problem . 22 Drug policy . 23 Drug seeking . 23 Drug substitution . 23 Drug testing . 24 Drug use . -

Alcohol Dependence, Withdrawal, and Relapse

Alcohol Dependence, Withdrawal, and Relapse Howard C. Becker, Ph.D. Continued excessive alcohol consumption can lead to the development of dependence that is associated with a withdrawal syndrome when alcohol consumption is ceased or substantially reduced. This syndrome comprises physical signs as well as psychological symptoms that contribute to distress and psychological discomfort. For some people the fear of withdrawal symptoms may help perpetuate alcohol abuse; moreover, the presence of withdrawal symptoms may contribute to relapse after periods of abstinence. Withdrawal and relapse have been studied in both humans and animal models of alcoholism. Clinical studies demonstrated that alcoholdependent people are more sensitive to relapse provoking cues and stimuli than nondependent people, and similar observations have been made in animal models of alcohol dependence, withdrawal, and relapse. One factor contributing to relapse is withdrawalrelated anxiety, which likely reflects adaptive changes in the brain in response to continued alcohol exposure. These changes affect, for example, the body’s stress response system. The relationship between withdrawal, stress, and relapse also has implications for the treatment of alcoholic patients. Interestingly, animals with a history of alcohol dependence are more sensitive to certain medications that impact relapselike behavior than animals without such a history, suggesting that it may be possible to develop medications that specifically target excessive, uncontrollable alcohol consumption. KEY WORDS: Alcoholism; alcohol dependence; alcohol and other drug (AOD) effects and consequences; neuroadaptation; AOD withdrawal syndrome; AOD dependence relapse; pharmacotherapy; human studies; animal studies he development of alcohol expectations about the consequences of drinking (Koob and Le Moal 2008). dependence is a complex and alcohol use. -

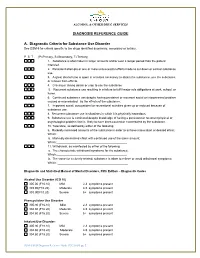

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Can Tobacco Dependence Provide Insights Into Other Drug Addictions? Joseph R

DiFranza BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:365 DOI 10.1186/s12888-016-1074-4 DEBATE Open Access Can tobacco dependence provide insights into other drug addictions? Joseph R. DiFranza Abstract Within the field of addiction research, individuals tend to operate within silos of knowledge focused on specific drug classes. The discovery that tobacco dependence develops in a progression of stages and that the latency to the onset of withdrawal symptoms after the last use of tobacco changes over time have provided insights into how tobacco dependence develops that might be applied to the study of other drugs. As physical dependence on tobacco develops, it progresses through previously unrecognized clinical stages of wanting, craving and needing. The latency to withdrawal is a measure of the asymptomatic phase of withdrawal, extending from the last use of tobacco to the emergence of withdrawal symptoms. Symptomatic withdrawal is characterized by a wanting phase, a craving phase, and a needing phase. The intensity of the desire to smoke that is triggered by withdrawal correlates with brain activity in addiction circuits. With repeated tobacco use, the latency to withdrawal shrinks from as long as several weeks to as short as several minutes. The shortening of the asymptomatic phase of withdrawal drives an escalation of smoking, first in terms of the number of smoking days/ month until daily smoking commences, then in terms of cigarettes smoked/day. The discoveries of the stages of physical dependence and the latency to withdrawal raises the question, does physical dependence develop in stages with other drugs? Is the latency to withdrawal for other substances measured in weeks at the onset of dependence? Does it shorten over time? The research methods that uncovered how tobacco dependence emerges might be fruitfully applied to the investigation of other addictions.