HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage Reduction Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background to the Celebration of Herbert D. Kleber (1904 -2018) by Thomas A

1 Background to the Celebration of Herbert D. Kleber (1904 -2018) by Thomas A. Ban By the mid-1990s the pioneering generation in neuropsychopharmacology was fading away. To preserve their legacy the late Oakley Ray (1931-2007), at the time Secretary of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP), generated funds from Solway Pharmaceuticals for the founding of the ACNP-Solway Archives in Neuropsychopharmacology. Ray also arranged for the videotaping of interviews (mainly by their peers) with the pioneers, mostly at annual meetings, to be stored in the archives. Herbert Kleber was interviewed by Andrea Tone, a medical historian at the Annual Meeting of the College held in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on December 7, 2003 (Ban 2011a; Kleber 2011a). The endeavor that was to become known as the “oral history project” is based on 235 videotaped interviews conducted by 66 interviewers with 213 interviewees which, on the basis of their content, were divided and edited into a 10-volume series produced by Thomas A. Ban, in collaboration with nine colleagues who were to become volume editors. One of them, Herbert Kleber, was responsible for the editing of Volume Six, dedicated to Addiction (Kleber 2011b). The series was published by the ACNP with the title “An Oral History of Neuropsychopharmacology Peer Interviews The First Fifty Years” and released at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the College in 2011 (Ban 2011b). Herbert Daniel Kleber was born January 19, 1934, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His family’s father’s side was from Vilnius, Lithuania, and the Mother’s side was from Germany. Both families came to the United State during the first decade of the 20th century. -

Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction

Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction a, a b Walter Ling, MD *, Larissa Mooney, MD , Li-Tzy Wu, ScD KEYWORDS • Addiction treatment • Depot naltrexone • Opioid dependence • Relapse KEY POINTS • The major problem with oral naltrexone is noncompliance. Administration of naltrexone as an intramuscular injection may be less onerous and improve compliance because it occurs only once a month (ie, extended-release depot naltrexone). • To initiate treatment with extended-release depot naltrexone, steps should be taken to ensure that the patient is sufficiently free from physical dependence on opioids (eg, detoxification). • Research on naltrexone in combination with other medications suggests many opportu- nities for studying mixed receptor activities in the treatment of opioid and other drug addictions. PERSPECTIVE ON OPIOID ANTAGONIST TREATMENT FOR ADDICTION Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist derived from the analgesic oxymorphone, was synthesized as EN-1639A by Blumberg and colleagues in 1967. Four years later, in 1971, naltrexone was selected for high-priority development as a treatment for opioid addiction by the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, an office created by President Nixon and put under the leadership of Dr Jerome Jaffe. Extinction Model The rationale for the antagonist approach to treating opioid addiction had been advanced by Dr Abraham Wikler a decade earlier, based largely on the extinction model explored in animal behavioral studies. It was believed that by blocking the euphorogenic effects of opioids at the opioid receptors, opiate use would become Disclosures: Dr Ling has served as a consultant to Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals and to Alkermes, Inc. Dr Mooney and Dr Wu report no relationships with commercial companies with any interest in the article’s subject matters. -

Flashbacks and HPPD: a Clinical-Oriented Concise Review

Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci - Vol. 51 - No 4 (2014) Flashbacks and HPPD: A Clinical-oriented Concise Review Arturo G. Lerner, MD,1-2 Dmitri Rudinski, MD,1 Oren Bor, MD,1 and Craig Goodman, PhD1 1 Lev Hasharon Mental Health Medical Center, Pardessya, Israel 2 Sackler School Of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel INTRODUCTION ABSTRACT Hallucinogens encompass a group of naturally occurring A unique characteristic of LSD, LSD-like and substances and synthetic substances (1) which may trigger a transient with hallucinogenic properties is the recurrence of some and generally reversible state of intoxication characterized or all the hallucinogenic symptoms which had appeared by perceptual disturbances primarily visual in nature, often during the intoxication after the immediate effects of the referred to as “trips” (2, 3). A unique characteristic of LSD substance had worn off. This recurring syndrome, mainly (lysergic acid diethylamide) and LSD-like substances is the visual, is not clearly understood. The terms Flashback total or partial recurrence of perceptual disturbances which and Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) appeared during previous intoxication and reappeared in have been used interchangeably in the professional the absence of voluntarily or involuntarily recent use (1-3). literature. We have observed at least two different This syndrome is still poorly understood (2, 3). LSD is the recurrent syndromes, the first Flashback Type we refer prototype of synthetic hallucinogenic substances and it is to as HPPD I, a generally short-term, non-distressing, probably the most investigated hallucinogen associated benign and reversible state accompanied by a pleasant with the etiology of this condition. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Novel Algorithms for the Prophylaxis and Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndromes–Beyond Benzodiazepines

Novel Algorithms for the Prophylaxis and Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndromes–Beyond Benzodiazepines José R. Maldonado, MD KEYWORDS Alcohol withdrawal Withdrawal prophylaxis Benzodiazepines Anticonvulsant agents Alpha-2 agonists Delirium tremens KEY POINTS Ethanol affects multiple cellular targets and neural networks; and abrupt cessation results in generalized brain hyper excitability, due to unchecked excitation and impaired inhibition. In medically ill, hospitalized subjects, most AWS cases (80%) are relatively mild and un- complicated, requiring only symptomatic management. The incidence of complicated AWS among patients admitted to medical or critical care units, severe enough to require pharmacologic treatment, is between 5% and 20%. Despite their proven usefulness in the management of complicated AWS, the use of BZDP is fraught with potential complications. A systematic literature review revealed that there are pharmacologic alternatives, which are safe and effective in the management of all phases of complicated AWS. BACKGROUND Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are maladaptive patterns of alcohol consumption mani- fested by symptoms leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.1 Ethanol is the second most commonly abused psychoactive substance (second to caffeine) and AUD is the most serious drug abuse problem in the United States2 and worldwide.3 The lifetime prevalences of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,4thedi- tion, alcohol abuse and dependence were 17.8% and 12.5%, respectively; the total life- time prevalence for any AUD was 30.3%.4 Alcohol consumption-related problems are the Psychosomatic Medicine Service, Emergency Psychiatry Service, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, 401 Quarry Road, Suite 2317, Stan- ford, CA 94305-5718, USA E-mail address: [email protected] Crit Care Clin 33 (2017) 559–599 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2017.03.012 criticalcare.theclinics.com 0749-0704/17/ª 2017 Elsevier Inc. -

ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update

The ASAM NATIONAL The ASAM National Practice Guideline 2020 Focused Update Guideline 2020 Focused National Practice The ASAM PRACTICE GUIDELINE For the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder 2020 Focused Update Adopted by the ASAM Board of Directors December 18, 2019. © Copyright 2020. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for commercial, advertising or promotional purposes, and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the fi rst page. Republication, systematic reproduction, posting in electronic form on servers, redistribution to lists, or other uses of this material, require prior specifi c written permission or license from the Society. American Society of Addiction Medicine 11400 Rockville Pike, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20852 Phone: (301) 656-3920 Fax (301) 656-3815 E-mail: [email protected] www.asam.org CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update 2020 Focused Update Guideline Committee members Kyle Kampman, MD, Chair (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD Chinazo Cunningham, MD, MS, FASAM Ben Nordstrom, MD, PhD Mark J. Edlund, MD, PhD David Oslin, MD Marc Fishman, MD, DFASAM George Woody, MD Adam J. Gordon, MD, MPH, FACP, DFASAM Tricia Wright, MD, MS Hendre´e E. Jones, PhD Stephen Wyatt, DO Kyle M. Kampman, MD, FASAM, Chair 2015 ASAM Quality Improvement Council (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD John Femino, MD, FASAM Marjorie Meyer, MD Margaret Jarvis, MD, FASAM, Chair Sandra Springer, MD, FASAM Margaret Kotz, DO, FASAM George Woody, MD Sandrine Pirard, MD, MPH, PhD Tricia E. -

Opioids and Nicotine Dependence in Planarians

Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 112 (2013) 9–14 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharmbiochembeh Opioid receptor types involved in the development of nicotine physical dependence in an invertebrate (Planaria)model Robert B. Raffa a,⁎, Steve Baron a,b, Jaspreet S. Bhandal a,b, Tevin Brown a,b,KevinSongb, Christopher S. Tallarida a,b, Scott M. Rawls b a Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Temple University School of Pharmacy, Philadelphia, PA, USA b Department of Pharmacology & Center for Substance Abuse Research, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA article info abstract Article history: Recent data suggest that opioid receptors are involved in the development of nicotine physical dependence Received 18 May 2013 in mammals. Evidence in support of a similar involvement in an invertebrate (Planaria) is presented using Received in revised form 18 September 2013 the selective opioid receptor antagonist naloxone, and the more receptor subtype-selective antagonists CTAP Accepted 21 September 2013 (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH )(μ, MOR), naltrindole (δ, DOR), and nor-BNI (norbinaltorphimine) Available online 29 September 2013 2 (κ, KOR). Induction of physical dependence was achieved by 60-min pre-exposure of planarians to nicotine and was quantified by abstinence-induced withdrawal (reduction in spontaneous locomotor activity). Known MOR Keywords: Nicotine and DOR subtype-selective opioid receptor antagonists attenuated the withdrawal, as did the non-selective Abstinence antagonist naloxone, but a KOR subtype-selective antagonist did not. An involvement of MOR and DOR, but Withdrawal not KOR, in the development of nicotine physical dependence or in abstinence-induced withdrawal was thus Physical dependence demonstrated in a sensitive and facile invertebrate model. -

What Are the Treatments for Heroin Addiction?

How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse? See page 3. from the director: Research Report Series Heroin is a highly addictive opioid drug, and its use has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug use—such as hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments—have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year. Although heroin use in the general population is rather low, the numbers of people starting to use heroin have been steadily rising since 2007.1 This may be due in part to a shift from abuse of prescription pain relievers to heroin as a readily available, cheaper alternative2-5 and the misperception that highly pure heroin is safer than less pure forms because it does not need to be injected. Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Medications HEROIN are available to treat heroin addiction while reducing drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms, improving the odds of achieving abstinence. There are now a variety of medications that can be tailored to a person’s recovery needs while taking into account co-occurring What is heroin and health conditions. Medication combined with behavioral therapy is particularly how is it used? effective, offering hope to individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. eroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to Hof poppy plants. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

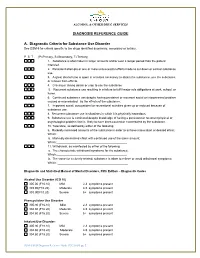

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder for Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families UPDATED 2020 TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT PROTOCOL TIP 63 Please share your thoughts about this publication by completing a brief online survey at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/KAPPFS The survey takes about 7 minutes to complete and is anonymous. Your feedback will help SAMHSA develop future products. TIP 63 MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER Treatment Improvement Protocol 63 For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families This TIP reviews three Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid use disorder treatment—methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine—and the other strategies and services needed to support people in recovery. TIP Navigation Executive Summary For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 1: Introduction to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 2: Addressing Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical Settings For healthcare professionals Part 3: Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare professionals Part 4: Partnering Addiction Treatment Counselors With Clients and Healthcare Professionals For healthcare and addiction professionals Part 5: Resources Related to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER TIP 63 Contents -

Myrtle Beach, SC May 24, 2019 New Drug Update 2019* *Presentation

New Drug Update 2019* *Presentation by Daniel A. Hussar, Ph.D. Dean Emeritus and Remington Professor Emeritus Philadelphia College of Pharmacy University of the Sciences Objectives: After attending this program, the participant will be able to: 1. Identify the new therapeutic agents and explain their appropriate use. 2. Identify the indications and mechanisms of action of the new drugs. 3. Identify the most important adverse events and other risks of the new drugs. 4. State the route of administration for each new drug and the most important considerations regarding dosage and administration. 5. Compare the new therapeutic agents with older medications to which they are most similar in properties and/or use, and identify the most important advantages and disadvantages of the new drugs. New Drug Comparison Rating (NDCR) system 5 = important advance 4 = significant advantage(s) (e.g., with respect to use/effectiveness, safety, administration) 3 = no or minor advantage(s)/disadvantage(s) 2 = significant disadvantage(s) (e.g., with respect to use/effectiveness, safety, administration) 1 = important disadvantage(s) Additional information The Pharmacist Activist monthly newsletter: www.pharmacistactivist.com Myrtle Beach, SC May 24, 2019 Erenumab-aooe (Aimovig – Amgen; Novartis) Agent for Migraine 2018 New Drug Comparison Rating (NDCR) = Indication: Administered subcutaneously for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults Comparable drugs: Beta-adrenergic blocking agents (e.g., propranolol); (fremanezumab [Ajovy] and galcanezumab [Emgality]