Cannabis Use During Methadone Maintenance Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCSS Guidance: Transfer from Methadone to Buprenorphine

PCSS Guidance Topic: Transfer from Methadone to Buprenorphine Original Author: Paul P. Casadonte, M.D. Last Updated: 12/5/13 (Maria A. Sullivan, M.D., Ph.D.) Guideline Coverage: TIP #40, Treatment Protocols: Patients dependent on long-acting opioids (pgs. 52-54) Clinical Questions: 1. Which patients receiving methadone should be considered good candidates for transfer to buprenorphine? 2. How should I transition a patient from methadone to buprenorphine? Background: Patients receiving methadone may seek transfer to buprenorphine treatment. There are a large number of clinical scenarios that would cause a patient receiving methadone to seek induction onto buprenorphine. It is incumbent upon the physician to weigh the clinical issues carefully prior to agreeing to assist in the transfer. If a patient is stable on methadone, it is generally not advisable to agree to transfer to buprenorphine without a careful evaluation of the factors motivating the desire to transfer. However, if in the physician's medical judgment, buprenorphine treatment is appropriate and the patient is well-informed of the risks and benefits, transfer may be a reasonable option. Among the potential benefits of transfer to buprenorphine include lower risk of overdose or sedation, lower risk of QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias, less severe withdrawal if a dose is missed, the capacity to obtain medication at a local pharmacy and the option of treatment in a doctor's office. A number of factors might motivate a patient's request to transfer from methadone. These -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 Mg, 10 Mg Rx Only

ROXANE LABORATORIES, INC. Columbus, OH 43216 DOLOPHINE® HYDROCHLORIDE CII (Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 mg, 10 mg Rx Only Deaths, cardiac and respiratory, have been reported during initiation and conversion of pain patients to methadone treatment from treatment with other opioid agonists. It is critical to understand the pharmacokinetics of methadone when converting patients from other opioids (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Particular vigilance is necessary during treatment initiation, during conversion from one opioid to another, and during dose titration. Respiratory depression is the chief hazard associated with methadone hydrochloride administration. Methadone's peak respiratory depressant effects typically occur later, and persist longer than its peak analgesic effects, particularly in the early dosing period. These characteristics can contribute to cases of iatrogenic overdose, particularly during treatment initiation and dose titration. In addition, cases of QT interval prolongation and serious arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) have been observed during treatment with methadone. Most cases involve patients being treated for pain with large, multiple daily doses of methadone, although cases have been reported in patients receiving doses commonly used for maintenance treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone treatment for analgesic therapy in patients with acute or chronic pain should only be initiated if the potential analgesic or palliative care benefit of treatment with methadone is considered and outweighs the risks. Conditions For Distribution And Use Of Methadone Products For The Treatment Of Opioid Addiction Code of Federal Regulations, Title 42, Sec 8 Methadone products when used for the treatment of opioid addiction in detoxification or maintenance programs, shall be dispensed only by opioid treatment programs (and agencies, practitioners or institutions by formal agreement with the program sponsor) certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and approved by the designated state authority. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Methadone Therapy for Opioid Dependence LAURIE LIMPITLAW KRAMBEER, PH.D., WILLIAM VON MCKNELLY, JR., M.D., WILLIAM F

Methadone Therapy for Opioid Dependence LAURIE LIMPITLAW KRAMBEER, PH.D., WILLIAM VON MCKNELLY, JR., M.D., WILLIAM F. GABRIELLI, JR., M.D., PH.D. and ELIZABETH C. PENICK, PH.D. University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas The 1999 Federal regulations extend the treatment options of methadone-maintained opi- oid-dependent patients from specialized clinics to office-based opioid therapy (OBOT). OBOT allows primary care physicians to coordinate methadone therapy in this group with ongo- ing medical care. This patient group tends to be poorly understood and underserved. Methadone maintenance therapy is the most widely known and well-researched treatment for opioid dependency. Goals of therapy are to prevent abstinence syndrome, reduce nar- cotic cravings and block the euphoric effects of illicit opioid use. In the first phase of methadone treatment, appropriately selected patients are tapered to adequate steady-state dosing. Once they are stabilized on a satisfactory dosage, it is often possible to address their other chronic medical and psychiatric conditions. The maintenance phase can be used as a long-term therapy until the patient demonstrates the qualities required for successful detox- ification. Patients who abuse narcotics have an increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus infection, hepatitis, tuberculosis and other conditions contributing to increased mor- bidity and mortality. Short- or long-term pain management problems and surgical needs are also common concerns in opioid-dependent patients and are generally treatable in conjunc- tion with methadone maintenance. (Am Fam Physician 2001;63:2404-10.) pioid dependence is a chronic, point in time.2,6,7 Gender differences exist, See editorial on page 2335. -

Methadone and the Anti-Medication Bias in Addiction Treatment

White, W. & Coon, B. (2003). Methadone and the anti-medication bias in addiction treatment. Counselor 4(5): 58-63. Methadone and the Anti-medication Bias in Addiction Treatment William L. White, MA and Brian F. Coon, MA, CADC An Introductory Note: This article is long overdue. Like many addiction counselors personally and professionally rooted in the therapeutic community and Minnesota model programs of the 1960s and 1970s, I exhibited a rabid animosity toward methadone and protected these beliefs in a shell of blissful ignorance. That began to change in the late 1970s when a new mentor, Dr. Ed Senay, gently suggested that the great passion I expressed on the subject of methadone seemed to be in inverse proportion to my knowledge about methadone. I hope this article will serve as a form of amends for that ignorance and arrogance. (WLW) There is a deeply entrenched anti-medication bias within the field of addiction treatment. This bias is historically rooted in the iatrogenic insults that have resulted from attempts to treat drug addiction with drugs. The most notorious of these professional practices includes: coaching alcoholics to substitute wine and beer for distilled spirits, treating alcoholism and morphine addiction with cocaine and cannabis, switching alcoholics from alcohol to morphine, failing repeatedly to find an alcoholism vaccine, employing aversive agents that linked alcohol or morphine to the experience of suffocation and treating alcoholism with drugs that later emerged as problems in their own right, e.g., barbiturates, amphetamines, tranquilizers, and LSD. A history of harm done in the name of good culturally and professionally imbedded a deep distrust of drugs in the treatment of alcohol and other drug addiction (White, 1998). -

ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update

The ASAM NATIONAL The ASAM National Practice Guideline 2020 Focused Update Guideline 2020 Focused National Practice The ASAM PRACTICE GUIDELINE For the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder 2020 Focused Update Adopted by the ASAM Board of Directors December 18, 2019. © Copyright 2020. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for commercial, advertising or promotional purposes, and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the fi rst page. Republication, systematic reproduction, posting in electronic form on servers, redistribution to lists, or other uses of this material, require prior specifi c written permission or license from the Society. American Society of Addiction Medicine 11400 Rockville Pike, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20852 Phone: (301) 656-3920 Fax (301) 656-3815 E-mail: [email protected] www.asam.org CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update 2020 Focused Update Guideline Committee members Kyle Kampman, MD, Chair (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD Chinazo Cunningham, MD, MS, FASAM Ben Nordstrom, MD, PhD Mark J. Edlund, MD, PhD David Oslin, MD Marc Fishman, MD, DFASAM George Woody, MD Adam J. Gordon, MD, MPH, FACP, DFASAM Tricia Wright, MD, MS Hendre´e E. Jones, PhD Stephen Wyatt, DO Kyle M. Kampman, MD, FASAM, Chair 2015 ASAM Quality Improvement Council (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD John Femino, MD, FASAM Marjorie Meyer, MD Margaret Jarvis, MD, FASAM, Chair Sandra Springer, MD, FASAM Margaret Kotz, DO, FASAM George Woody, MD Sandrine Pirard, MD, MPH, PhD Tricia E. -

Significantly More Intense Pain in Methadone-Maintained Patients Who Are Addicted to Nicotine

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 36), pp: 60576-60580 Clinical Research Paper Significantly more intense pain in methadone-maintained patients who are addicted to nicotine Lian-Zhong Liu1,*, Lin-Xiang Tan2,*, Yan-Min Xu1, Xue-Bing Liu1, Wen-Cai Chen1, Jun-Hong Zhu1, Jin Lu3 and Bao-Liang Zhong1 1Affiliated Wuhan Mental Health Center (The Ninth Clinical School), Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China 2Mental Health Education Center, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan Province, China 3Department of Psychiatry, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, Yunnan Province, China *These authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: Xue-Bing Liu, email: [email protected] Jin Lu, email: [email protected] Bao-Liang Zhong, email: [email protected] Keywords: pain, smoking, nicotine dependence, heroin dependence, methadone Received: May 30, 2017 Accepted: June 29, 2017 Published: July 13, 2017 Copyright: Liu et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Pain and cigarette smoking are very common in heroin-dependent patients (HDPs) receiving methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and both have substantial negative effects on HDPs’ physical and mental health. Nevertheless, very few studies have assessed the relationship between the two in HDPs. This study examined the association between pain intensity and smoking in Chinese methadone-maintained HDPs. A total of 603 HDPs were consecutively recruited from three MMT clinics in Wuhan, China, and administered with a socio-demographic and drug use questionnaire, a smoking questionnaire concerning average number of cigarettes smoked daily and Heaviness of Smoking Index, and Zung’s Self-rating Depression Scale. -

What Are the Treatments for Heroin Addiction?

How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse? See page 3. from the director: Research Report Series Heroin is a highly addictive opioid drug, and its use has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug use—such as hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments—have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year. Although heroin use in the general population is rather low, the numbers of people starting to use heroin have been steadily rising since 2007.1 This may be due in part to a shift from abuse of prescription pain relievers to heroin as a readily available, cheaper alternative2-5 and the misperception that highly pure heroin is safer than less pure forms because it does not need to be injected. Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Medications HEROIN are available to treat heroin addiction while reducing drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms, improving the odds of achieving abstinence. There are now a variety of medications that can be tailored to a person’s recovery needs while taking into account co-occurring What is heroin and health conditions. Medication combined with behavioral therapy is particularly how is it used? effective, offering hope to individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. eroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to Hof poppy plants. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

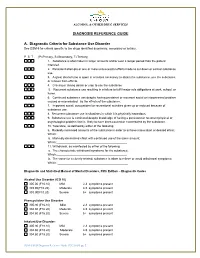

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b.