Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit: Opioid Use Disorder Facts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Safety Notice 009/20 Acetylfentanyl and Fentanyl In

Safety Notice 009/20 Acetylfentanyl and fentanyl in non-opioid illicit drugs 16 October 2020 Background Distributed to: A cluster of hospitalisations due to unexpected opioid toxicity recently occured on • Chief Executives the Central Coast of NSW. Acetylfentanyl and fentanyl are circulating in NSW and • Directors of Clinical Governance may be misrepresented as or be adulterants in illicit cocaine or ketamine. • Director Regulation and Acetylfentanyl has a similar potency to fentanyl, both may cause serious harm and Compliance Unit death. People who do not use opioids regularly (‘opioid naïve’) may be unintentionally exposed and are at high risk of overdose. Even people who Action required by: regularly use opioids are at risk due to the relatively high potency of fentanyl and • Chief Executives acetylfentanyl. • Directors of Clinical Changes in illicit drug use in 2020, as well as variations in purity and alternative Governance ingredients, may be associated with unusual presentations and overdose. • Director Regulation and Compliance Unit Case management • We recommend you also Have a high index of suspicion for illicit fentanyl and fentanyl analogues in inform: suspected opioid overdose. This includes people who deny opioid use or • Drug and Alcohol Directors report use of other non-opioid illicit drugs including ketamine or stimulants and staff such as cocaine, but who present clinically with signs of an opioid • All Service Directors overdose. • Emergency Department • Intensive Care Unit • Airway management, oxygenation, and ventilation support take precedence • Toxicology Units over naloxone, where appropriate. • Ambulance • Cases may require titrated doses of naloxone with a higher total dose of • All Toxicology Staff 800 micrograms or more. -

What Are the Treatments for Heroin Addiction?

How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse? See page 3. from the director: Research Report Series Heroin is a highly addictive opioid drug, and its use has repercussions that extend far beyond the individual user. The medical and social consequences of drug use—such as hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, fetal effects, crime, violence, and disruptions in family, workplace, and educational environments—have a devastating impact on society and cost billions of dollars each year. Although heroin use in the general population is rather low, the numbers of people starting to use heroin have been steadily rising since 2007.1 This may be due in part to a shift from abuse of prescription pain relievers to heroin as a readily available, cheaper alternative2-5 and the misperception that highly pure heroin is safer than less pure forms because it does not need to be injected. Like many other chronic diseases, addiction can be treated. Medications HEROIN are available to treat heroin addiction while reducing drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms, improving the odds of achieving abstinence. There are now a variety of medications that can be tailored to a person’s recovery needs while taking into account co-occurring What is heroin and health conditions. Medication combined with behavioral therapy is particularly how is it used? effective, offering hope to individuals who suffer from addiction and for those around them. eroin is an illegal, highly addictive drug processed from morphine, a naturally occurring substance extracted from the seed pod of certain varieties The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has developed this publication to Hof poppy plants. -

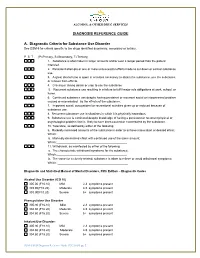

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Brain Injury and Opioid Overdose

Brain Injury and Opioid Overdose: Acquired Brain Injury is damage to the brain 2.8 million brain injury related occurring after birth and is not related to congenital or degenerative disease. This includes anoxia and hospital stays/deaths in 2013 hypoxia, impairment (lack of oxygen), a condition consistent with drug overdose. 70-80% of hospitalized patients are discharged with an opioid Rx Opioid Use Disorder, as defined in DSM 5, is a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment, manifested by meaningful risk 63,000+ drug overdose-related factors occurring within a 12-month period. deaths in 2016 Overdose is injury to the body (poisoning) that happens when a drug is taken in excessive amounts “As the number of drug overdoses continues to rise, and can be fatal. Opioid overdose induces respiratory doctors are struggling to cope with the increasing number depression that can lead to anoxic or hypoxic brain of patients facing irreversible brain damage and other long injury. term health issues.” Substance Use and Misuse is: The frontal lobe is • Often a contributing factor to brain injury. History of highly susceptible abuse/misuse is common among individuals who to brain oxygen have sustained a brain injury. loss, and damage • Likely to increase for individuals who have misused leads to potential substances prior to and post-injury. loss of executive Acute or chronic pain is a common result after brain function. injury due to: • Headaches, back or neck pain and other musculo- Sources: Stojanovic et al 2016; Melton, C. Nov. 15,2017; Devi E. skeletal conditions commonly reported by veterans Nampiaparampil, M.D., 2008; Seal K.H., Bertenthal D., Barnes D.E., et al 2017; with a history of brain injury. -

SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention TOOLKIT

SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention TOOLKIT Opioid Use Disorder Facts Five Essential Steps for First Responders Information for Prescribers Safety Advice for Patients & Family Members Recovering From Opioid Overdose TABLE OF CONTENTS SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit Opioid Use Disorder Facts.................................................................................................................. 1 Scope of the Problem....................................................................................................................... 1 Strategies to Prevent Overdose Deaths.......................................................................................... 2 Resources for Communities............................................................................................................. 4 Five Essential Steps for First Responders ........................................................................................ 5 Step 1: Evaluate for Signs of Opioid Overdose ................................................................................ 5 Step 2: Call 911 for Help .................................................................................................................. 5 Step 3: Administer Naloxone ............................................................................................................ 6 Step 4: Support the Person’s Breathing ........................................................................................... 7 Step 5: Monitor the Person’s Response .......................................................................................... -

Examining Opioid and Heroin-Related Drug Overdose In

health Center for Health and Environmental Data watch November 2016 No. 100 Office of eHealth and Data • Health Surveys & Evaluation Branch Examining Opioid and Heroin-Related Drug • Public Health Overdose in Colorado Informatics Branch Allison Rosenthal, MPH • Registries and Vital SAMHSA/CSTE Applied Epidemiology Fellow, Violence and Injury Prevention Statistics Branch - Mental Health Promotion Branch; Kirk Bol, MSPH Registries and Vital Statistics Branch; Barbara Gabella, MSPH Violence and Injury Prevention - Mental Health Promotion Branch. Background Nationally and in Colorado, opioid use disorders have emerged as a significant public health concern. Starting in the 1990s, opioid prescriptions (or, pain medications such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and their combination with acetaminophen) began to rise nationwide partially due to the promotion of extended-release tablets and a change in prescriber culture to recognize the needs of patients with chronic pain (Okie, 2010). The dramatic increase in use has been associated with dependency, addiction, and other adverse health events including, but not limited to: heroin use disorders, spread of hepatitis infections and HIV, and fatal drug overdose (Bonhert et al, 2011; Garland et al, 2014; Paulozzi et al, 2006; Peters et al, 2016; Suryaprasad et al, 2014; and Young & Havens, 2011). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates that from 2013-2014, 4.9 percent of the Colorado population of ages 12 years and older used prescription pain relievers non-medically (95% CI: 4.0-6.1%), which is similar to the national rate (4.1%, 95% CI: 3.9-4.2%). The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is monitoring the severity of the epidemic using a variety of available data, including mortality data from death certificates registered in Colorado. -

Risk of Death Associated with Kratom Use Compared to Opioids T ⁎ Jack E

Preventive Medicine 128 (2019) 105851 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Preventive Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ypmed Risk of death associated with kratom use compared to opioids T ⁎ Jack E. Henningfielda,b, , Oliver Grundmannc, Jane K. Babind, Reginald V. Fanta, Daniel W. Wanga, Edward J. Conea,b a PInneyAssociates, Bethesda, MD, United States of America b The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, United States of America c College of Pharmacy, Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States of America d The Law Office of Jane K. Babin, PC, San Diego, CA, J.D. University of San Diego School of Law, J.D. Law, Purdue University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Kratom use appears to be increasing across the United States, increasing attention to deaths in which kratom use Kratom was detected. Most such deaths have been ascribed to fentanyl, heroin, benzodiazepines, prescription opioids, Mitragynine cocaine and other causes (e.g., homicide, suicide and various preexisting diseases). Because kratom has certain Opioids opioid-like effects (e.g., pain relief), and is used by some people as a substitute for opioids for pain or addiction, Mortality risk kratom has been compared to “narcotic-like opioids” (e.g., morphine) with respect to risk of death despite Opioid epidemic evidence that its primary alkaloid, mitragynine, carries little of the signature respiratory depressing effects of morphine-like opioids. This commentary summarizes animal toxicology data, surveys and mortality data asso- ciated with opioids and kratom to provide a basis for estimating relative mortality risk. Population-level mor- tality estimates attributed to opioids as compared to kratom, and the per user mortality risks of opioids as compared to kratom are provided. -

Kratom Science Brief Columbus Ohio Public Hearing by Jack E

Kratom Science Brief Columbus Ohio Public Hearing By Jack E. Henningfield, PhD Vice President, Research, Health Policy and Abuse Liability PinneyAssociates, Bethesda, Maryland Professor, Adjunct, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine January 28, 2020 I would like to provide some background on the current state of kratom science, its place in public health, and the opioid epidemic in particular. I’d also like to review how our current knowledge can help determine the most appropriate way to regulate kratom in order to minimize risks to kratom consumers, while contributing to their health and wellbeing, as well as to the public health. During the 1980s and 1990s I headed the Clinical Pharmacology laboratory of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and led research across a wide range of substances including opioids, cannabis, cocaine and other stimulants, and a myriad of other drugs. I also worked NIDA, FDA and DEA on drug scheduling issues. I have published nearly 450 papers on these topics and contribute to numerous federal and international reports. I consult on pharmaceutical development and have contributed to the research and/or approval of for most treatments approved for drug, alcohol and nicotine addiction since the 1980s and have advised NIDA, CDC, FDA, the World Health Organization, and other organizations since then. I advise the American Kratom Association on kratom science. That began as a pro bono effort when DEA proposed placing kratom in Schedule I in 2016. My efforts were focused on setting the record straight because my colleagues and I at PinneyAssociates (a team with extensive opioid and other drug experience) believed that DEA and FDA were wrong on the science and policy, and worse, that banning kratom would result in the quick establishment of a deadly kratom black market. -

OXYCONTIN Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION day, 25 mg oral oxymorphone per day, 60 mg oral hydrocodone per day, or These highlights do not include all the information needed to use an equianalgesic dose of another opioid. (2.1) ® OXYCONTIN safely and effectively. See full prescribing information • Use the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration consistent with for OXYCONTIN. individual patient treatment goals (2.1). OXYCONTIN® (oxycodone hydrochloride) extended-release tablets, for • Individualize dosing based on the severity of pain, patient response, prior oral use, CII analgesic experience, and risk factors for addiction, abuse, and misuse. Initial U.S. Approval: 1950 (2.1) • Instruct patients to swallow tablets intact and not to cut, break, chew, crush, WARNING: ADDICTION, ABUSE AND MISUSE; LIFE- or dissolve tablets (risk of potentially fatal dose). (2.1, 5.1) THREATENING RESPIRATORY DEPRESSION; ACCIDENTAL • Instruct patients to take tablets one at a time, with enough water to ensure INGESTION; NEONATAL OPIOID WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME; complete swallowing immediately after placing in mouth. (2.1, 5.10) CYTOCHROME P450 3A4 INTERACTION; and RISKS FROM • Do not abruptly discontinue OXYCONTIN in a physically dependent CONCOMITANT USE WITH BENZODIAZEPINES AND OTHER patient. (2.9) CNS DEPRESSANTS See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. Adults: For opioid-naïve and opioid non-tolerant patients, initiate with 10 mg • OXYCONTIN exposes users to risks of addiction, abuse and misuse, tablets orally every 12 hours. See full prescribing information for instructions which can lead to overdose and death. Assess patient’s risk before on conversion from opioids to OXYCONTIN, titration and maintenance of prescribing and monitor regularly for these behaviors and conditions. -

Opioid Use Disorders

AD APTING YOUR PRACTIC E Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders Opioid Use Disorders March 2014 ADAPTING YOUR PRACTICE Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network March 2014 Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network Adapting Your Practice: Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders was developed with support from the Bureau of Primary Health Care, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. All material in this document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission. Citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Suggested citation: Meges D, Zevin B, Cookson E, Bascelli L, Denning P, Little J, Doe-Simkins M, Wheeler E, Watlov Phillips S, Bhalla P, Nance M, Cobb G, Tankanow J, Williamson J, Post P (Ed.). Adapting Your Practice: Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders. 102 pages. Nashville: Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians' Network, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc., 2014. DISCLAIMER This publication was made possible by grant number U30CS09746 from the Health Resources & Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Health Resources & Services Administration. i ADAPTING YOUR PRACTICE Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network PREFACE Clinicians experienced in homeless health care routinely adapt their practice to foster better outcomes for their patients. -

HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage Reduction Or

This HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Analgesics provides advice to clinicians who are contemplating or initiating a reduction in opioid dosage or discontinuation Appropriate Dosage Reduction of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. In each case the clinician should review the risks and benefits of the or Discontinuation of current therapy with the patient, and decide if tapering is appropriate based on individual circumstances. Long-Term Opioid Analgesics After increasing every year for more than a decade, annual needs.2,3,4 Coordination across the health care team is critical. opioid prescriptions in the United States peaked at 255 million in Clinicians have a responsibility to provide or arrange for 2012 and then decreased to 191 million in 2017.i More judicious coordinated management of patients’ pain and opioid-related opioid analgesic prescribing can benefit individual patients as problems, and they should never abandon patients.2 More well as public health when opioid analgesic use is limited to specific guidance follows, compiled from published guidelines situations where benefits of opioids are likely to outweigh risks. (the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain2 At the same time opioid analgesic prescribing changes, such and the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy as dose escalation, dose reduction or discontinuation of long- for Chronic Pain3) and from practices endorsed in the peer- term opioid analgesics, have potential to harm or put patients at reviewed literature. risk if not made in a thoughtful, deliberative, collaborative, and measured manner.