Ancient Narrative Volume 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012.02.01 Jeffrey RUSTEN, the Birth of Comedy

CJ -Online, 2012.02.01 BOOK REVIEW The Birth of Comedy: Texts, Documents, and Art from Athenian Comic Competitions, 486–280 . Edited by Jeffrey RUSTEN . Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. Pp. xx + 794. Hardcover, $110.00/£57.00. ISBN 978-0- 8018-9448-0. The world of Greek comedy has always been a mysterious universe for amateurs. The naive enthusiasm of Renaissance intellectuals, who, immediately after the publication of the editio princeps of the eleven Aristophanic comedies, edited their complete translations (without footnotes!) in Latin (Andreas Divus) and Italian (the Rositini brothers), has decreased as time has passed. In contrast to the fate of Greek tragedies, Aristophanes’ and Menander’s comedies have always been rare- ly performed; even the most recent translations cannot refrain from using ex- planatory notes if they want their readers to understand the nuances of the Greek text. Apart from the two main authors, the other comic poets (Cratinus, Eupolis, Alexis, Diphilus, Philemon) are almost unknown, in spite of the good reputation they had in the ancient world. From this point of view the difference with tragedy is even greater: among the majority of people, the three tragic poets of the fifth century BCE enjoy a much wider popularity than the single representative of ancient Greek comedy; Menander’s popularity (a fairly recent one, based on the papyrological discoveries of the last century) cannot compete with that of his Roman followers, Plautus and Terence. But things are changing: since the end -

Roman Literature from Its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age

The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I by John Dunlop This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I Author: John Dunlop Release Date: April 1, 2011 [Ebook 35750] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. VOLUME I*** HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE, FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. IN TWO VOLUMES. BY John Dunlop, AUTHOR OF THE HISTORY OF FICTION. ivHistory of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I FROM THE LAST LONDON EDITION. VOL. I. PUBLISHED BY E. LITTELL, CHESTNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA. G. & C. CARVILL, BROADWAY, NEW YORK. 1827 James Kay, Jun. Printer, S. E. Corner of Race & Sixth Streets, Philadelphia. Contents. Preface . ix Etruria . 11 Livius Andronicus . 49 Cneius Nævius . 55 Ennius . 63 Plautus . 108 Cæcilius . 202 Afranius . 204 Luscius Lavinius . 206 Trabea . 209 Terence . 211 Pacuvius . 256 Attius . 262 Satire . 286 Lucilius . 294 Titus Lucretius Carus . 311 Caius Valerius Catullus . 340 Valerius Ædituus . 411 Laberius . 418 Publius Syrus . 423 Index . 453 Transcriber's note . 457 [iii] PREFACE. There are few subjects on which a greater number of laborious volumes have been compiled, than the History and Antiquities of ROME. -

Title Page Diss

Pre-Modern Iberian Fragments in the Present: Studies in Philology, Time, Representation and Value By Heather Marie Bamford A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Jesús Rodríguez-Velasco, Co-Chair Professor José Rabasa, Co-Chair Professor Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht Professor Ignacio Navarrete Professor David Hult Fall 2010 1 Abstract Pre-Modern Iberian Fragments in the Present: Studies in Philology, Time, Representation, and Value by Heather Marie Bamford Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Literatures and Languages University of California, Berkeley Professors Jesús Rodríguez-Velasco and José Rabasa, Co-Chairs This dissertation examines the uses of medieval and early-modern Iberian cultural objects in the present. It draws on the notion of fragment and actual fragmentary testimonies to study how pre- modern Iberian things and texts are reconstituted and used for various projects of personal, institutional, national and transnational reconstitution in the present. The corpus objects are necessarily diverse in chronological scope, with examples from the medieval, early-modern and modern periods, and touch upon works of many genres: chivalric romance, royal and personal correspondence, early-modern and modern historiography, Hispano-Arabic and Hispano-Hebrew lyric, inscriptions, pre-modern and modern biographies and 21st century book exhibitions. The dissertation proposes that Iberian fragments are engaged in various forms of reconstitution or production in the present and, at the same time, are held as timeless, unchanging entities that have the capability to allow users to connect with something genuinely old, truly Spanish and, indeed, eternal. -

Terence's Plays

chapter 2 Terence’s Plays: Commentary and Illustration from Manuscript to Print 2.1 Terence as an Educational Classic: Text and Commentary from Antiquity to Medieval and Renaissance Europe Publius Terentius Afer, or Terence, was the author of six plays which premiered in Rome between 166 and 160 bc— Andria, Heauton timorumenos, Eunuchus, Phormio, Hecyra, and Adelphoe. Some information on the circumstances of the production of each play can be obtained from the didascaliae,1 while the prologues reveal that they were produced in a vibrant and at times vitriolic literary environment. A biographical tradition concerning Terence only devel- oped much later; in the early second century ad Suetonius wrote a Life, which was subsequently supplemented and attached to the commentary of Aelius Donatus (for which see below), while in Late Antiquity it appears that another very brief Life, known as the Vita Ambrosiana, was composed, which provides a few facts independent of the Life found in Donatus.2 In these traditions, we are told that Terence came originally from Carthage in Northern Africa (hence his cognomen, Afer, or ‘the African’); that he was taken to Rome at a young age as a slave, and was adopted and freed there by a senator, Terentius Lucanus, from whom he took his name, and by whom he was educated; that he subsequently was befriended by some of the leading figures in Roman society associated with Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (185/ 4– 129 bc); and that he died young on a trip to Greece, where he had gone in order to purchase more comedies to translate. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D

CHAPTER 6 • OBJECTIVE Ancient Rome and Early Trace the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, and analyze its impact on Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 culture, government, and religion. Previewing Main Ideas Previewing Main Ideas Urge students to look for connections POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers between the three main ideas. For exam- called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. ple, point out that Rome’s rise to an Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch empire led to the spread of Christianity. from east to west? Emphasize the universality of human EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three desires for power and authority, as well continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought as for a spiritual connection. peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? Accessing Prior Knowledge RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, Ask students to list any ancient Romans or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of that they can name (Possible Answers: Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Julius Caesar, Mark Antony) and discuss Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the what they already know about them. spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? Invite students to share their knowledge of early Christianity and Judaism. Tell them that Christianity comes from the INTERNET RESOURCES Greek word christos, meaning “messiah” • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: or “savior.” • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice Geography Answers • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz POWER AND AUTHORITY The Roman Empire stretched about 3,500 miles from east to west. -

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in Their Contexts and As Evidence of His World Map

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in their Contexts and as Evidence of his World Map Christopher B. Krebs American Journal of Philology, Volume 139, Number 1 (Whole Number 553), Spring 2018, pp. 93-122 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ajp.2018.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687618 Access provided at 25 Oct 2019 22:25 GMT from Stanford Libraries THE WORLD’S MEASURE: CAESAR’S GEOGRAPHIES OF GALLIA AND BRITANNIA IN THEIR CONTEXTS AND AS EVIDENCE OF HIS WORLD MAP CHRISTOPHER B. KREBS u Abstract: Caesar’s geographies of Gallia and Britannia as set out in the Bellum Gallicum differ in kind, the former being “descriptive” and much indebted to the techniques of Roman land surveying, the latter being “scientific” and informed by the methods of Greek geographers. This difference results from their different contexts: here imperialist, there “cartographic.” The geography of Britannia is ultimately part of Caesar’s (only passingly and late) attested great cartographic endeavor to measure “the world,” the beginning of which coincided with his second British expedition. To Tony Woodman, on the occasion of his retirement as Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia, in gratitude. IN ALEXANDRIA AT DINNER with Cleopatra, Caesar felt the sting of curiosity. He inquired of “the linen-wearing Acoreus” (linigerum . Acorea, Luc. 10.175), a learned priest of Isis, whether he would illuminate him on the lands and peoples, gods and customs of Egypt. Surely, Lucan has him add, there had never been “a visitor more capable of the world” than he (mundique capacior hospes, 10.183). -

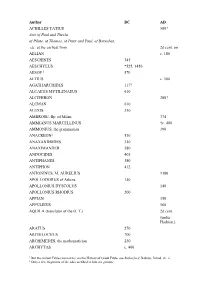

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Document Resume Ed 047 563 Fl 002 036 Author Title Institution Pub Date

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 047 563 FL 002 036 AUTHOR Willcock, M. M. TITLE The Present State of Homeric Studies. INSTITUTION Joint Association of Classical Teachers, Oxford (England). PUB DATE 67 NOTE 11p. JOURNAL CIT Didaskalos; v2 n2 p59-69 1967 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Classical Literature, *Epics, *Greek, *Greek Literature, Historical Reviews, Humanism, Literature Reviews, Oral Reading, *Poetry, *Surveys, World Literature IDENTIFIEIAS *Homer, Iliad, Odyssey ABSTRACT A personal point of view concerning various aspects of Homerica characterizes this brief state-of-the-art report. Commentary is directed to:(1) first readers; (2) the Parry-Lord approach to the study of the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey" as representatives of a type of oral, formulaic, poetry;(3) analysts, unitarians, and neo-analysts; (4) recent publications by British scholars;(5) archaeology and history; (6) language and meter; and (7) the "Odyssey". (RL) fromDidaskalos; v2 n2 p59-69 1967 The present state of Homeric studies teN 1111 m.M. WILL COCK U.S. DEPARTMENT OF MOH. EDUCATION d WELFARE Nft OFFICE OF EDUCATION ".74P THIS DOCUMENT HAS BUN REPRODUCED EAACTLYAS RECEIVED ROM THE VIcV4 OD OPoivs PERSON OR ORGANIZAME eRI43!!th!!!!r:!I . V.1.14TI OF EDUCATION Ca STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE Um, POSITION OR POLICY. A select reading-list of Homerica, with a running com- Introduction mentary, cannot fail to be invidious. There is little chance that one person can fairly survey the vast fieldAll that I can offer is my own view-point, more literary than archaeological or linguistic. As to the limits of the survey, I have endeavoured to go far enough back in each separate aspect to clarify the present situation. -

Chapter 4: the Self-Governing Cities: Elements and Rhythms of Urbanization

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/66262 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Pellegrino, F. Title: The urbanization of the North-Western provinces of the Roman Empire : a juridical and functional approach to town life in Roman Gaul, Germania inferior and Britain Issue Date: 2018-10-17 CHAPTER 4: THE SELF-GOVERNING CITIES: ELEMENTS AND RHYTHMS OF URBANIZATION Introduction Provincial civitas capitals, as had been the case with the cities in the Italian peninsula, required structures that would allow the cives to participate in public and political life. This does not translate into the Romans forcing indigenous communities to develop civic spaces.423 Rather, as Emilio Gabba would say, the Roman government was expecting and encouraging these new semi-autonomous centres and their elites to provide the citizens with suitable areas and buildings where they could fulfil their newly acquired rights and obligations.424 In this sense, we can understand why the process of urbanization in the north-western provinces followed some common lines, consequential to their political integration in the Empire.425 At the same time, it is important to remember that this process took place over decades and even centuries. For example, in Belgica, a large majority of cities were not equipped with public buildings until a considerable time had elapsed after they were conquered and annexed to the Roman Empire. Most of the public structures began to be built from AD 50 onwards. In Flavian times construction of imposing infrastructure for public use began on an unprecedented scale. It would reach its full dimensions only in the mid-2nd century AD.426 The relatively slow pace of urbanization that characterized the early years of the north-western provinces suggests that sustainable revenues were essential to the development and progress of cities. -

An Iliad by Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare Based on Homer’S the Iliad, Translated by Robert Fagles

AN ILIAD BY LISA PETERSON AND DENIS O’HARE BASED ON HOMER’S THE ILIAD, TRANSLATED BY ROBERT FAGLES DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. AN ILIAD Copyright © 2013, Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of AN ILIAD is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Authors’ agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for AN ILIAD are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. -

Theopompus' Homer

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications Classics 2020 Theopompus’ Homer: Paraepic in Old and Middle Comedy Matthew C. Farmer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/classics_facpubs THEOPOMPUS’ HOMER: PARAEPIC IN OLD AND MIDDLE COMEDY MATTHEW C. FARMER T IS A STRIKING FACT that, out of the twenty titles preserved for the late fifth- and early fourth-century comic poet Theopompus, three directly reference I Homer’s Odyssey: Odysseus, Penelope, and Sirens. In one fragment (F 34) preserved without title but probably belonging to one of these plays, Odysseus himself is the speaking character; he quotes the text of the Odyssey, approv- ingly.1 Another fragment (F 31), evidently drawn from a comedy with a more contemporary focus, mocks a politician in a run of Homeric hexameters. Theo- pompus was, it seems, a comic poet with a strong interest in paraepic comedy, that is, in comedy that generates its humor by parodying, quoting, or referring to Homeric epic poetry. In composing paraepic comedy, Theopompus was operating within a long tra- dition. Among the earliest known Homeric parodies, Hipponax provides our first certain example, a fragment in which the poet invokes the muse and deploys Homeric language to mock a glutton (F 128). The Margites, a poem composed in a mixture of hexameters and trimeters recounting the story of a certain fool in marked Homeric language, may have been composed as early as the seventh cen- tury BCE, but was certainly known in Athens by the fifth or fourth.2 In the late