IN PORTUGAL Br the SAME AUTHOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Elements Are Simple

THE ELEMENTS ARE SIMPLE Rigid, lightweight panels are 48 inches wide and 6 ft, 8 ft, 10 ft, 12 ft, 14 ft long and can be installed either vertically, horizontally, wall mounted or freestanding. In addition to the standard panel, the greenscreen® system of green facade wall products includes the Column Trellis, customized Crimp-to-Curve shapes, panel trims and a complete selection of engineered attachment solutions. Customiziation and adaptation to unique project specifications can easily become a part of your greenscreen® project. The panels are made from recycled content, galvanized steel wire and finished with a baked on powder coat for durability. National Wildlife Federation Headquarters - Reston, VA basic elements greenscreen® is a three-dimensional, welded wire green facade wall system. The distinctive modular trellis panel is the building block of greenscreen.® Modular Panels Planter Options Custom Use for covering walls, Planter options are available for a Using our basic panel as the building freestanding fences, screens variety of applications and panel block, we are always available to and enclosures. heights. Standard 4 ft. wide fiberglass discuss creative options. Panels planter units support up to 6' tall can be notched, cut to create a Standard Sizes: screens, and Column planters work taper, mitered and are available in width: 48” wide with our standard diameter Column crimped-to-curve combinations. length: 6’, 8’, 10’, 12’, 14’ Trellis. Our Hedge-A-Matic family of thickness: 3" standard planters use rectangle, curved and Custom dimensions available in 2" Colors square shapes with shorter screens, increments, length and width. for venues like patios, restaurants, Our standard powder coated colors See our Accessory Items, Mounting entries and decks. -

Inspired by Arne Maynard

Inspired by Arne Maynard N ENGLISHMAN’S HOME IS HIS CASTLE, AND any manor house calls for well maintained gardens designed in harmony with the architectural style. A Arne Maynard is the landscape architect who is commissioned to uphold the heritage. He was a garden designer for the landscaped park at Cottisbrooke Hall, a grand Queen Anne mansion in Northamptonshire. He was commissioned to design the grounds at Dyrham Park for the National Trust, and gardens at the medieval manor house, Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. Arne has an unmistakable design signature, creating a quintessentially English country house garden. His sense of capturing the history of a place sets his gardens apart, so that one steps into its timelessness. Almost, but not quite effortless. The tall herbaceous borders of wildflowers are breezy but never overgrown, held in check by the trimmed box shaping the flowerbeds. It’s a finely tuned instinct to get the balance right between evoking a timeless meadow of wildflowers or a wilderness of overgrown flowers. Rambling roses trail purposefully around doorways and window frames. Arne brings a sense of order, with parterre topiary box hedging shaping the expanse, while pollarded trees stand like sentinels. Photos Britt Willoughby Dyer 65 INSPIRED BY His sense of structure is honed by a background in architecture. “I chose to study architecture, probably because I didn’t think I could make much of a career out of gardens, but I didn’t ever settle into my course,” he admits. His first and foremost love was gardening. “I love buildings, but it is their relationship with the landscape around them that excites me. -

Trellis & Fountain

rellis and Fountain T Ah, the sound of water on a summer’s day seems to cool everything down while also soothing the soul. The combination of trellis and fountain is an easy way to add a water feature to your outdoor living area without huge expense. Choose a statuary that fits in your garden and build the trellis yourself. 1 Materials § 26 linear feet of 4 x 4 pine § 17 linear feet of 2 x 2 pine § 18 linear feet of 1 x 4 pine § 4’ x 8’ sheet of privacy lattice § 6 linear feet of 2 x 4 pine Hardware § 50, 2-1/2” wood screws § 20, 1-5/8” wood screws § 30, 1” wire brads § 2, 5” lag screws § Fountain statuary piece* § Fountain pump § Plastic hose (sized to connect the statuary piece to the pump) § Galvanized bucket, approximately 3’ x 4’ x 2’ Special Tools and Techniques § Miter *Notes on Materials This trellis will work with any statuary fountain piece. Most lawn and garden stores sell a variety of designs. Or you can convert a wall plaque into a fountain piece by drilling a hold through the plaque to accommodate the plastic pump hose. Be sure to purchase a pump large enough to pump the water from the tank up the height of your fountain piece. Check the pump manufacturer’s specifications to be sure. Cutting List Code Description Qty. Materials Dimensions A Side 2 4 x 4 pine 120” long B Side Supports 2 2 x 2 pine 96” long C Connectors 4 1 x 4 pine 48” line D Trellis 1 Lattice 4’ x 8’ sheet E Top 2 2 x 4 pine 26” long 2 F Ledge 1 4 x 4 pine 55” long Building the Frame 1. -

Landscape Vines for Southern Arizona Peter L

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1606 October 2013 LANDSCAPE VINES FOR SOUTHERN ARIZONA Peter L. Warren The reasons for using vines in the landscape are many and be tied with plastic tape or plastic covered wire. For heavy vines, varied. First of all, southern Arizona’s bright sunshine and use galvanized wire run through a short section of garden hose warm temperatures make them a practical means of climate to protect the stem. control. Climbing over an arbor, vines give quick shade for If a vine is to be grown against a wall that may someday need patios and other outdoor living spaces. Planted beside a house painting or repairs, the vine should be trained on a hinged trellis. wall or window, vines offer a curtain of greenery, keeping Secure the trellis at the top so that it can be detached and laid temperatures cooler inside. In exposed situations vines provide down and then tilted back into place after the work is completed. wind protection and reduce dust, sun glare, and reflected heat. Leave a space of several inches between the trellis and the wall. Vines add a vertical dimension to the desert landscape that is difficult to achieve with any other kind of plant. Vines can Self-climbing Vines – Masonry serve as a narrow space divider, a barrier, or a privacy screen. Some vines attach themselves to rough surfaces such as brick, Some vines also make good ground covers for steep banks, concrete, and stone by means of aerial rootlets or tendrils tipped driveway cuts, and planting beds too narrow for shrubs. -

With Sketches of Spain and Portugal

iiiiUiLuiiiiiiuiHuiiiiiniiiffniiniriiiifiminiiii! ITALY; WITH SKETCHES OF SPAIN AND PORTUGAL. VOL. II. : LONDON PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY, Dorset Street, Fleet Street. ITALY; WITH SKETCHES OF SPAIN AND PORTUGAL. BY THE AUTHOR OF "VATHEK." SECOND EDITION, REVISED. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. n. LONDON; RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET, 3Piiblt)Si)fr in (©rtimary to W^ iMajetitg. 1834. — CONTENTS THE SECOND VOLUME. PORTUGAL. LETTER I. Detained at Falmouth.—Navigation at a stop.—An even- ing ramble. ..... Page 5 LETTER IL Mines in the parish of Gwynnap.—Piety and gin.—Rapid progress of Methodism.—Freaks of fortune. —Pernicious extravagance. — Minerals. — Mr. Beauchamp's mansion. — still Beautiful lake.—The wind contrary. 8 LETTER IIL A lovely morning. — Antiquated mansion,—Its lady.—An- cestral effigies.—Collection of animals.—Serene evening. Owls.—Expected dreams. .12 LETTER IV. A blustering night. —Tedium of the language of the compass.—Another excursion to Trefusis. 16 VOL. II. b VI CONTENTS. LETTER V. Regrets produced by contrasts. .19 LETTER VL Still no prospect of embarkation.—Pen-dennis Castle. —Luxuriant vegetation—A serene day. —Anticipations of the voyage. 21 LETTER VIL Portugal. —Excursion to Pagliavam.—The villa. —Dismal labyrinths in the Dutch style. — Roses.—Anglo-Portuguese Master of the Horse— Interior of the Palace. — Furniture in petticoats. —Force of education.—Royalty without power. —Return from the Palace. .23 LETTER VIIL Glare of the climate in Portugal.—Apish luxury. —Bo- tanic Gardens.— A9afatas. —Description of the Gardens and Terraces. .... 29 LETTER IX. Consecration of the Bishop of Algarve.—Pathetic Music. —Valley of Alcantara. — Enormous Aqueduct.—Visit to the Marialva Palace.—Its much revered Masters. -

Tours Around the Algarve

BARLAVENTO BARLAVENTO Região de Turismo do Algarve SAGRES TOUR SAGRES SAGRES TOUR SAGRES The Algarve is the most westerly part of mainland Europe, the last harbouring place before entering the waters of the Atlantic, a region where cultures have mingled since time immemorial. Rotas & Caminhos do Algarve (Routes and Tours of the Algarve) aims to provide visitors with information to help them plan a stay full of powerful emotions, a passport to adventure, in which the magic of nature, excellent hospitality, the grandeur of the Algarve’s cultural heritage, but also those luxurious and cosmopolitan touches all come together. These will be tours which will lure you into different kinds of activity and adventure, on a challenge of discovery. The hundreds of beaches in the Algarve seduce people with their white sands and Atlantic waters, which sometimes surge in sheets of spray and sometimes break on the beaches in warm waves. These are places to relax during lively family holidays, places for high-energy sporting activity, or for quiet contemplation of romantic sunsets. Inland, there is unexplored countryside, with huge areas of nature reserves, where you can follow the majestic flight of eagles or the smooth gliding of the storks. Things that are always mentioned about the people of the Algarve are their hospitality and their prowess as story-tellers, that they are always ready to share experiences, and are open to CREDITS change and diversity. The simple sophistication of the cuisine, drawing inspiration from the sea and seasoned with herbs, still Property of the: Algarve Tourism Board; E-mail: [email protected]; Web: www.visitalgarve.pt; retains a Moorish flavour, in the same way as the traditional Head Office: Av. -

Arbor, Trellis, Or Pergola—What's in Your Garden?

ENH1171 Arbor, Trellis, or Pergola—What’s in Your Garden? A Mini-Dictionary of Garden Structures and Plant Forms1 Gail Hansen2 ANY OF THE garden features and planting Victorian era (mid-nineteenth century) included herbaceous forms in use today come from the long and rich borders, carpet bedding, greenswards, and strombrellas. M horticultural histories of countries around the world. The use of garden structures and intentional plant Although many early garden structures and plant forms forms originated in the gardens of ancient Mesopotamia, have changed little over time and are still popular today, Egypt, Persia, and China (ca. 2000–500 BC). The earliest they are not always easy to identify. Structures have been gardens were a utilitarian mix of flowering and fruiting misidentified and names have varied over time and by trees and shrubs with some herbaceous medicinal plants. region. Read below to find out more about what might be in Arbors and pergolas were used for vining plants, and your garden. Persian gardens often included reflecting pools and water features. Ancient Romans (ca. 100) were perhaps the first to Garden Structures for People plant primarily for ornamentation, with courtyard gardens that included trompe l’oeil, topiary, and small reflecting Arbor: A recessed or somewhat enclosed area shaded by pools. trees or shrubs that serves as a resting place in a wooded area. In a more formal garden, an arbor is a small structure The early medieval gardens of twelfth-century Europe with vines trained over latticework on a frame, providing returned to a more utilitarian role, with culinary and a shady place. -

Bambuco, Tango and Bolero: Music, Identity, and Class Struggles in Medell´In, Colombia, 1930–1953

BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 by Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado B.S. in Music (harpsichord), Ponti¯cia Universidad Javeriana, 1997 M.A. in Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Music in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2006 BAMBUCO, TANGO AND BOLERO: MUSIC, IDENTITY, AND CLASS STRUGGLES IN MEDELL¶IN, COLOMBIA, 1930{1953 Carolina Santamar¶³aDelgado, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This dissertation explores the articulation of music, identity, and class struggles in the pro- duction, reception, and consumption of sound recordings of popular music in Colombia, 1930- 1953. I analyze practices of cultural consumption involving records in Medell¶³n,Colombia's second largest city and most important industrial center at the time. The study sheds light on some of the complex connections between two simultaneous historical processes during the mid-twentieth century, mass consumption and socio-political strife. Between 1930 and 1953, Colombian society experienced the rise of mass media and mass consumption as well as the outbreak of La Violencia, a turbulent period of social and political strife. Through an analysis of written material, especially the popular press, this work illustrates the use of aesthetic judgments to establish social di®erences in terms of ethnicity, social class, and gender. Another important aspect of the dissertation focuses on the adoption of music gen- res by di®erent groups, not only to demarcate di®erences at the local level, but as a means to inscribe these groups within larger imagined communities. -

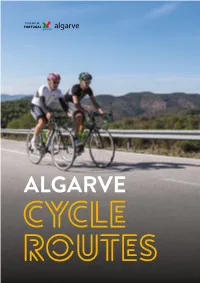

Algarve, Cycle Routes .PDF

contents 06 The easTern algarve rouTes 08 Level 1 13 Level 2 16 Level 3 18 Level 4 22 The CenTral algarve rouTes 24 Level 1 31 Level 2 33 Level 3 35 Level 4 38 The WesTern algarve rouTes 40 Level 1 45 Level 2 47 Level 3 49 Level 4 52 sporTs Training rouTes 54 Level 3 58 Level 4 62 uphill areas 64 Eastern Algarve 68 Central Algarve 72 Western Algarve 76 geographiCal CharacterisaTion 78 ClimaTiC CharacterisaTion Cycle RoutEs | INTRODUCTION the algarve The AlgArve offers ouTstanding condiTions for All sorTs of cycling. The geogrAphicAl And orogrAphic chArAcTerisTics of The region, The climate, The quAliTy And diversiTy of The roAds, TrAcks And TrAils, The weAlTh of hisTory And culTure, And The wonderful people All combine To mAke This A fAbulous desTination for An AcTiviTy That is becoming increAsingly populAr All over The world. Cycle RoutEs | INTRODUCTION Boasting a vast array of natural attractions, the Algarve’s authentic charm wins over residents and visitors alike. the enchanting coast is lined with long, golden sandy beaches and modern towns and cities; and inland, there are delightful and welcoming villages waiting to be discovered. From the sophisticated coastal resorts to the old country trails through the barrocal, along roads that wind their way through abundant nature and forests, or open up on to wide valleys and hills, there are endless opportunities in this sunny region for unforgettable outings at any time of year. Promoting this leading destination and its appeal in terms of leisure activities is the aim of the first Algarve Cycle Routes. -

Planta Silves.Cdr

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 São Marcos da Serra São Bartolomeu de Messines 1 Lisboa Enxerim A E A 5 B B 6 9 Fragura C 1 C 2 3 10 B 8 4 Alcantarilha Armação de Pêra B Faro A22 D Portimão D Monchique A 7 N 0 50 100m W E Escala 1:5 000 silves E S Portimão Lagoa Faro © Região de Turismo do Algarve. É expressamente proibida a reprodução, mesmo parcial, para todo e qualquer fim sem a prévia autorização escrita do proprietário. A22 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mapa Turístico de Tourist Map Carte Touristique de SILVES Touristischer Stadtplan PATRIMÓNIO GUARDA NACIONAL REPUBLICANA PORTO DE CRUZEIROS PISCINAS Guardia Nacional Republicana / Gendarmerie Nationale Puerto de Cruceros / Port de Croisière Piscinas / Piscines National Republican Guard (Police) / Republikanische Nationalgarde Cruise Ship Harbour / Kreuzfahrthafen Swimming-Pools / Schwimmbad 1 C 4 Sé Velha C 4 Igreja da Misericórdia CENTRO DE SAÚDE CÂMARA MUNICIPAL CAMPO DE GOLFE 2 Centro de salud / Centre de santé Ayuntamiento / Mairie Campo de golf / Terrain de golf 3 C 3 Capela de Na. Sra. dos Mártires Health center / Gesundheitsamt City Hall / Rathaus Golf course / Golfplatz 4 D 4 Pelourinho FARMÁCIA POSTO DE TURISMO ZONA VINÍCOLA Farmacia / Pharmacie Oficina de Turismo / Office du Tourisme Zona Vinícola / Zone Vinicole 5 A 6 Cruz de Portugal Chemist / Apotheke Tourist Office / Tourismusbüro Wine-growing area / Weinanbaugebiet 6 C 4 Castelo BOMBEIROS ESTAÇÃO DOS CORREIOS PRAIA 7 D 4 Ponte Romana Bomberos / Pompiers Correos / Bureau de Poste Playa / Plage Fire brigade / Feuerwehr Post Office / Postamt Beach / Strand 8 C 4 Museu de Arqueologia ESTAÇÃO FERROVIÁRIA MERCADO MUNICIPAL RIO, BARRAGEM 9 C 5 Museu da Cortiça Estación de Tren / Gare des Trains Mercado / Marché Río, embalse / Fleuve, barrage Railway Station / Zugbahnhof Market / Markt River, dam / Fluss, Damm 10 C 4 Centro de Interpretação do Património Islâmico Algarb TRIBUNAL FONTES TAXIS Tribunal / Tribunal Fuentes / Fontaines Concelho / Municipio / Canton / Municipality / Bezirk 11 Igreja Matriz (Pêra) Court House / Gericht Fountains / Springbrunnen Igreja da Ordem Terceira de S. -

Ferragudo-Albufeira

Sistemas Aquíferos de Portugal Continental SISTEMA AQUÍFERO: FERRAGUDO – ALBUFEIRA (M4) Figura M4.1 – Enquadramento litoestratigráfico do sistema aquífero Ferragudo-Albufeira Sistema Aquífero: Ferragudo-Albufeira (M4) 466 Sistemas Aquíferos de Portugal Continental Identificação Unidade Hidrogeológica: Orla Meridional Bacia Hidrográfica: Ribeiras do Sotavento e Arade Distrito: Faro Concelhos: Albufeira, Lagoa e Silves Enquadramento Cartográfico Folhas 594, 595, 603, 604 e 605 da Carta Topográfica na escala 1:25 000 do IGeoE Folhas 49-C, 49-D, 52-A e 52-B do Mapa Corográfico de Portugal na escala 1:50 000 do IPCC Folhas 52-A e 52-B da Carta Geológica de Portugal na escala 1:50 000 do IGM SILVES 49D LOULÉ 49C PORTIMÃO 595 596 594 LAGOA LAGOS ALBUFEIRA 603 604 605 52A 52B Figura M4.2 – Enquadramento geográfico do sistema aquífero Ferragudo-Albufeira Enquadramento Geológico Estratigrafia e Litologia As formações aquíferas dominantes são os Arenitos de Sobral (Cretácico), os Calcários e Margas com Palorbitolina (Cretácico), a Formação Carbonatada de Lagos-Portimão (Miocénico) e as Areias e Cascalheiras de Faro-Quarteira (Quaternário). Os Arenitos de Sobral, do Berriasiano, são constituídos por bancadas de arenitos siliciosos com calhaus de quartzo e por siltes ocres a violáceos, com cerca de 30 metros de espessura (Rey, 1983). Os Calcários e Margas com Palorbitolina são constituídos por alternâncias de margas amarelas e acastanhadas com nódulos calcários, calcários esparíticos com calciclastos e oólitos, e algumas bancadas dolomíticas ou finamente -

Alan Lomax in Asturias

ALAN LOMAX IN ASTURIAS November 1952 Aurelia de Caso, en Cabrales, mostrando el vexigu de mazar la manteca / Una colaboración del Association for Cultural Equity y del Muséu del Pueblu Aurelia de Caso, in Cabrales, with vexigu. d’Asturies. / A collaboration of the Association for Cultural Equity and the Muséu del Pueblu d’Asturies. Cover image: El / !e Corri-Corri: 2010 Odyssey Productions, Inc. for !e Estate of Alan Lomax. Trinidad Gutiérrez Butillo, Fernánda Ardinez García, Angela Mestas López, www.culturalequity.org Josefa Moradiellos Cifuentes, y / and Leonor Cuervo. Arenas de Cabrales. ALAN LOMAX IN ASTURIAS SIERO, CABRALES, LLANES Alan Lomax (1915–2002). “Los vientos y los arroyos de Asturias se oyen al fondo…” DE LA RESPONSABLE GENERAL DE LAS GRABACIONES HECHAS POR ALAN LOMAX EN ESPAÑA “!e sounds of the winds and the streams of Asturias can be heard in the background…” Con este CD doble, empezamos un nuevo nivel de colaboración con nuestros —Alan Lomax, colegas en España. Fernando Ornosa y sus compañeros del Muséu del Pueblu Notas a la edición en disco / notes to the Spanish recordings on LP, d’Asturies y la “Association for Cultural Equity” de Nueva York hemos trabajado Westminster 12021, 1950s. juntos para preparar las grabaciones históricas que hizo Alan Lomax en Asturias en octubre y noviembre del año 1952. Quisiera también agradecer a Eliseo Parra, que me sugirió la posibilidad de trabajar con Fernando Ornosa y nos puso en contacto. En el verano de 2003, visité Asturias como parte del jurado del concurso de Na- velgas (Tinéu), y entrevisté algunos de los cantantes de estas grabaciones.