Abhinaya in Bharatanatyam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rukmini Devi Arundale January 6, 2021 Rukmini Devi Arundale(1904 – 1986) “I was very intuitive from an early age. I responded to people just as I responded to art – through an inner feeling which is difficult to explain. I just felt some things were right and some were not…” Rukmini Devi was born on 29 February 1904 in Madurai of Tamilnadu. She was the first woman in Indian history to be nominated a member of the Rajya Sabha. Rukmini Devi Arundale was an Indian theosophist, dancer, and choreographer of the Indian classical dance form of Bharatnatyam, and an activist for Animal welfare. The most important revivalist of Bharatanatyam from its original ‘sadhir’ style prevalent amongst the temple dancers, the Devadasis, she also worked for the re- establishment of traditional Indian arts and crafts. She was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1956 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 1967. In January 1936, she along with her husband established Kalakshetra, an academy of dance and music, built around the ancient Indian Gurukul system, at Adyar, at Chennai. Today the academy is a deemed university under the Kalakshetra Foundation. She also became very close to Annie Besant and helped her with her work. She went on to become the President of the Theosophical Society after Dr. Besant’s passing and Rukmini Devi herself was an active member of the Theosophical movement. She gave her first performance at the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the Theosophical Society in 1935. Theosophists hailed her as the World Mother, to her family in Kalakshetra she is Athai (paternal aunt). -

USER MANUAL Artiste: M.S

248. Anu Dinamunu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Ramanathapuram Srinivasa Iyengar 249. Naraveshabhushana Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Traditional Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 250. Manju Nihar Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Annamalai Reddiar 251. Muzhudai Unarndavar USER MANUAL Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Athma visit www.saregama.com/carvaanmini to download the entire songlist 44 239. Sirai Aarum Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Thirugnana Sambandar 240. Sada Saranga Nayane Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Mysore H. Yoganarasimham 241. Vanajaakshi 1. Overview - Buttons and Ports 3 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Traditional 242. Tum Ho Jag Ke 2. Modes 5 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Ustad Mohd. Dilshad Khan Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 3. Playback Status Light 8 243. Ko Va Rago Vadito Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Mysore H Yoganarasimham 4. Battery 8 Music Director: Gurunanak Shabad, P.S.Srinivasa Rao 244. Mere To Giridhar Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Gowri Ramanarayanan 5. Safety Handling 8 Composer: Meera 245. Varuga Varugave 6. Warranty Overview 10 Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Ambujam Krishna 246. Sai Charan Ma 7. Song List 18 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Suresh Dalal Music Director: Ashit Desai 247. Dinudanenu Devuduvu Nivu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Annamacharya 2 43 231. Oru Thram Saravana Bhava Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Overview - Buttons and Ports Lyricist: Traditional Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 232. Maanilathai Vaazha Vaika Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Kalki R.Krishnamurthy Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 233. Nee Saati Daivamu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Previous Composer: Muthuswami Dikshitar 234. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

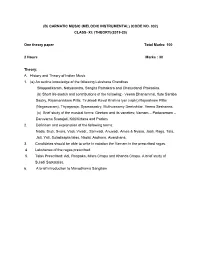

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

Senior School Curriculum 2017-18

SENIOR SCHOOL CURRICULUM 2017-18 VOLUME - III Music and Dance for Class XII Central Board of Secondary Education “Shiksha Sadan”, 17, Rouse Avenue, New Delhi – 110 002 / Telephone : +91-11-23237780 /Website : www.cbseacademic.in Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE Senior School Curriculum 2017 - 18 Volume - III CBSE, Delhi – 110092 March, 2017 Copies: Price: ` This book or part thereof may not be reproduced by any person or Agency in any manner Published by: The Secretary, CBSE Printed by: Multi Graphics, 8A/101, WEA Karol Bagh, New Delhi – 110 005, Phone: 25783846 Printed by: II Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE CONTENTS Page No. Music and Dance Syllabus (i) Carnatic Music 1 (a) Carnatic Music (Vocal) 2 (b) Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrument) 6 (c) Carnatic Music (Percussion Instrumental) 10 (ii) Hindustani Music 15 (a) Hindustani Music (Vocal) 16 (b) Hindustani Music (Melodic Instrument) 19 (c) Hindustani Music (Percussion Instrumental) 22 (iii) (a) Dances 25 (a) Kathak 27 (b) Bharatnatyam 32 (c) Kuchipudi 36 (d) Odissi 38 (e) Manipuri 42 (f) Kathakali 46 (g) Mohiniyattam 49 III Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE SENIOR SCHOOL CURRICULUM 2017-18 VOLUME III (i) Carnatic Music Effective from the academic session 2017–2018 for Classes–XI and XII 1 Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE (A) CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL): (CODE NO. 031) CLASS–XII (2017-18): (THEORY) One Theory Paper Total Marks: 100 3 Hours Marks: 30 72 Periods Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) Brief history of Carnatic music with special reference to Sangita Saramrita, Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini, Svaramelakalanidhi, Raga Vibodham, Brihaddesi. -

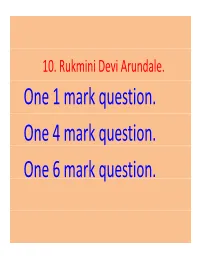

One 1 Mark Question. One 4 Mark Question. One 6 Mark Question

10. Rukmini Devi Arundale. One 1 mark question. One 4 mark question. One 6 mark question. Content analysis About Rukmini Devi Arundale. Born on 29‐02‐1904 Father Neelakantha StiSastri Rukmini Devi Arundale Rukmini Devi Liberator of classical dance. India’s cultural queen. Rukmini Devi Fearless crusader for socilial c hange. Champion of vegetarianism. Andhra art of vegetable-dyed Kalmakari Textile crafts like weaving silk an d cotton a la (as prepared in) Kanchipuram Banyan tree at Adyar Rukmini Devi The force that shaped the future of Rukmini Devi Anna Pavlova Anna Pavlova Wraith-like ballerina (Wraith-like =otherworldly) Her meeting with Pavlova. First meeting : In 1924, in London at the Covent Gardens. Her meeting with Pavlova. Second meeting: Time : At the time of annual Theosophical Convention at Banaras. Place : Bombay - India. The warm tribute of Pavlova Rukmini Devi: I wish I could dance like you, but I know I never can. The warm tribute of Pavlova Anna Pavlova:NonoYoumust: No, no. You must never say that. You don’t have to dance, for if you just walk across the stage, it will be enouggph. People will come to watch you do just that. Learning Sadir. She learnt Sadir, the art of Devadasis . Hereditary guru : Meenakshisundaram Pillai. Duration: Two years. First performance At the International Theosophical Conference Under a banyan tree In 1935. reaction Orthodox India was shocked . The first audience adored her revelatory debut. The Bishop of Madras confessed that he felt like he had attended a benediction. Liberating the Classical dance. Changes made to Sadir. Costume and jewellery were of good taste. -

Visionary Craft

Chennai • CITY EDITION • FEBRUARY 28, 2020 Arts | Dance | Music | Movies www.thehindu.com/FridayReview Theatre | Review | History & Culture | Faith Lakshmi Viswanathan CCCCCCCCCCCCCCC of the soul to the Highest. It needs the sential feature of India’s art is that it is same devotion, the same great flights A leap year child, founded on a spiritual outlook,” she et me begin by paying my of imagination that produces reli Rukmini Devi said. She often emphasised that “ homage to the founder of gious feeling. Added to these are the spirituality” was above religion. “In Kalakshetra, Rukmini De creative spirit which, blossoming out Arundale was also a India there is no religion apart from vi Arundale. I knew her, of the artist produces great works of nonpolitical activist our daily lives.” interacted with her, and art. Think of some of the great tem in my own modest way, ples and the bronze images of South and a woman known Path-breaking experiments Lhelped her with some of her thought India. These were not made by so for her refined Such clear thinking moulded her ful ventures like the Kalakshetra Jour- phisticated people… they may not vision for dance and thus was born nal. I admired her as a leader of In even be able to speak to us about ab aesthetic sense the institution Kalakshetra. She was dian culture, a thinker and a creative stract philosophy… nevertheless they the first to understand the value of a artiste. She knew that the arts have to were the people who created master school for dance. -

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

The Journal of the Music Academy Madras Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

The Journal of Music Academy Madras ISSN. 0970-3101 Publication by THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar (Tamil) Part I, II & III each 150.00 Part – IV 50.00 Part – V 180.00 The Journal Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar of (English) Volume – I 750.00 Volume – II 900.00 The Music Academy Madras Volume – III 900.00 Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Volume – IV 650.00 Volume – V 750.00 Vol. 89 2018 Appendix (A & B) Veena Seshannavin Uruppadigal (in Tamil) 250.00 ŸÊ„¢U fl‚ÊÁ◊ flÒ∑ȧá∆U Ÿ ÿÊÁªNÔUŒÿ ⁄UflÊÒ– Ragas of Sangita Saramrta – T.V. Subba Rao & ◊jQÊ— ÿòÊ ªÊÿÁãà ÃòÊ ÁÃDÊÁ◊ ŸÊ⁄UŒH Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in English) 50.00 “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; Lakshana Gitas – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman 50.00 (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra The Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin 50.00 (Sanskrit Text with supplement) E Krishna Iyer Centenary Issue 25.00 Professor Sambamoorthy, the Visionary Musicologist 150.00 By Brahma EDITOR Sriram V. Raga Lakshanangal – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in Tamil) Volume – I, II & III each 150.00 VOL. 89 – 2018 VOL. COMPUPRINT • 2811 6768 Published by N. Murali on behalf The Music Academy Madras at New No. 168, TTK Road, Royapettah, Chennai 600 014 and Printed by N. Subramanian at Sudarsan Graphics Offset Press, 14, Neelakanta Metha Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 014. Editor : V. Sriram. THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS ISSN. -

FINE ARTS ART and CULTURE ‡ Bhangra (Punjab) - Folk Dance of Harvest Season, Coinciding with the Festival of Baisakhi

78 FINE ARTS ART AND CULTURE ‡ Bhangra (Punjab) - folk dance of harvest season, coinciding with the festival of Baisakhi. ‡ Lalit Kala Academy was set up in 1954 at New Delhi. ‡ Tamasha (Maharashtra) - Nautanki (U.P.), Garba ‡ Sangeet natak Academy was established in 1953 at (Gujarat), Chhow (Orissa, Bihar). New Delhi. Its function is to conduct survey ‡ There are two forms of music in India - Carnatic and research of different art forms in India. Hindustani. ‡ Sahitya Academy was established in 1954 at New ‡ Sama Veda deals with music. Delhi. Its aim is to encourage production of high ‡ Purandaradas gave shape and form to Carnatic class literature in several languages of India. music. ‡ The National Book Trust of India was set up in ‡ The trinity of Carnatic music is Thyagaraja, Syama 1957. Shastri and Muthuswami Dikshitar. ‡ ASI - Archaeological Survey of India - was established in 1861. Its headquarters is in New Names Associated with Indian Music: Delhi. ‡ Ustad Alla Rakha - A master of the Tabla. ‡ Indian Council for Cultural Relations was established ‡ Bala Murali Krishna - A singer of Carnatic music. in 1950, and it strives to promote and to strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between ‡ Bhim Sen Joshi - A Hindustani singer. India and other countries. The Council administers ‡ Pt. Hari Prasad Chaurasya - Flute player. the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for the promotion of ‡ Pt. Jasraj - Famous singer of Hindustani music. peace and international understanding. ‡ Parveen Sulthana - Hindustan style singer. ‡ NSD - National School of Drama - was set up in 1959 in Delhi. ‡ Neralathu Ramapothuval - Sopanam. ‡ Dances : There are two main branches of Indian ‡ M.S.Subha Lakshmi - Carnatic music.