Vitis International Variety Catalogue \(VIVC\)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

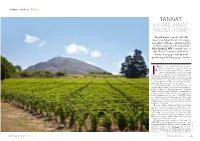

Tannat: Home Away from Home

feature / vinifera / Tannat TANNAT: HOME AWAY FROM HOME From Tannat’s contested South American debut, back to its origins in southwest France, and forward to its latest outposts in New Zealand, Julia Harding MW charts the rise of this climate-sensitive and terroir- transparent grape variety, now producing a thrilling range of wines orget the tango and dulce de leche, the competitive debate now simmering concerns Tannat’s first home in South America. Those waving the Argentine flag claim that the variety was brought to their country toward the end of the 19th century byF the Basque farmer Juan Jáuregui (born in Irouleguy in 1812), who traveled from Bordeaux to Montevideo in 1835, moving north to Salto before crossing the River Uruguay and settling in Concordia in the province of Entre Ríos in southern Argentina, immediately opposite the Uruguayan town of Salto. According to Alberto Moroy, a specialist in Argentinian and Uruguayan history, writing in Uruguay’s national newspaper El Pais in March 2016, Jáuregui planted the first Tannat cuttings in Concepción in 1861, brought over from France by his nephew Pedro Jáuregui. They apparently came via his paternal grandfather from the estate of Louis XVI. (Moroy’s account is based on a book by Frenchman Alexis Pierre Louis Edouard Peiret, A visit to the Colonies of the Argentine Republic, published in Buenos Airesin 1889.) Jáuregui was also the first to make wine in Concordia. The story continues with another Basque, Don Pascual Harriague (1819–94), who emigrated from Lapurdi (Labourd) to Uruguay in 1838 and settled in Montevideo. In 1840 he moved north to Salto, which is where he became interested in farming and eventually in grape-growing. -

WINE Talk: October 2016

Licence No 58292 30 Salamanca Square, Hobart GPO Box 2160, Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Australia Telephone +61 3 6224 1236 [email protected] www.livingwines.com.au WINE Talk: October 2016 The newsletter of Living Wines: Edition 65 Since the last newsletter we have travelled to Melbourne and Geelong to conduct wine tastings and also to Sydney to attend the high-energy Mental Notes event which, this year, was held at the Paddington Town Hall – an excellent venue for an event of this type. We also joined with a number of our other colleagues from this event to hold a trade tasting at The Bentley Bar and Restaurant on the Monday following Mental Notes. We are now gearing up for the other two major events on the natural wine calendar – Rootstock in Sydney and Soul For Wine in Melbourne. We are delighted that both Tony and Philippe Bornard will be attending Rootstock this year. To celebrate their visit we will be holding two very special events. The first will be a late lunch in Hobart at Franklin Restaurant and the second will be a dinner at the wonderful Bar Brosé in Sydney which will be cooked by Analeise Gregory as described below. And now to the special packs. We have a rather long story on the Côte de Beaune and a 6 pack of wines selected from that region of Burgundy. We have a special dozen comprised of wines that include very rare grape varieties that we like to seek out from the hidden corners of France. There is a pack of wines from our winemaker of the month, namely Domaine les Grandes Vignes from the Loire Valley. -

1. from the Beginnings to 1000 Ce

1. From the Beginnings to 1000 ce As the history of French wine was beginning, about twenty-five hundred years ago, both of the key elements were missing: there was no geographi- cal or political entity called France, and no wine was made on the territory that was to become France. As far as we know, the Celtic populations living there did not produce wine from any of the varieties of grapes that grew wild in many parts of their land, although they might well have eaten them fresh. They did cultivate barley, wheat, and other cereals to ferment into beer, which they drank, along with water, as part of their daily diet. They also fermented honey (for mead) and perhaps other produce. In cultural terms it was a far cry from the nineteenth century, when France had assumed a national identity and wine was not only integral to notions of French culture and civilization but held up as one of the impor- tant influences on the character of the French and the success of their nation. Two and a half thousand years before that, the arbiters of culture and civilization were Greece and Rome, and they looked upon beer- drinking peoples, such as the Celts of ancient France, as barbarians. Wine was part of the commercial and civilizing missions of the Greeks and Romans, who introduced it to their new colonies and later planted vine- yards in them. When they and the Etruscans brought wine and viticulture to the Celts of ancient France, they began the history of French wine. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Fps Grape Program Newsletter

FPS GRAPE PROGRAM NEWSLETTER fps.ucdavis.edu OCT O BER 2012 From the Director: A Fruitful Year of Expansion by Deborah Golino On May 4, 2012, Foundation An ongoing major initiative for Plant Services supporters the FPS grapevine program is celebrated the dedication of the new Foundation Vineyard the Trinchero Family Estates at Russell Ranch. On page Building. We greatly enjoyed 14, Mike Cunningham details having so many stakeholders the vineyard preparations, join us for this special event. vine training and impressive Dean Neal Van Alfen welcomed numbers of qualified grapevines our guests; among them were added in 2012. Such progress Bob and Roger Trinchero In Progress: Trinchero Family Estates Building at FPS attests to the close cooperation representing the Trinchero Photo by Justin Jacobs of each person at FPS across family, donor Francis Mahoney, every function. Funding for this and the family of Pete Christensen, late Viticulture Foundation Vineyard was provided by the National Clean Specialist in the Department of Viticulture and Enology. Plant Network, a major new USDA program that benefits Having this event timed between the National Clean Plant clean plant centers for specialty crops at public institutions. Network Tier II Grapes annual meeting and Rose Day This is the final year of NCPN funding from the current allowed many distant guests to attend, including State farm bill. We hope that this program will continue to back and Federal regulatory officials, scientists from around us up as we fulfill our role as the foundation of registered the country, and many of our client nurseries. Photos of grapevine plants for growers and nurseries. -

Vitis Vinifera L.)

Theor Appl Genet (2013) 126:401–414 DOI 10.1007/s00122-012-1988-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Large-scale parentage analysis in an extended set of grapevine cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) Thierry Lacombe • Jean-Michel Boursiquot • Vale´rie Laucou • Manuel Di Vecchi-Staraz • Jean-Pierre Pe´ros • Patrice This Received: 19 June 2012 / Accepted: 15 September 2012 / Published online: 27 September 2012 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2012 Abstract Inheritance of nuclear microsatellite markers cultivars, (2) 100 full parentages confirming results estab- (nSSR) has been proved to be a powerful tool to verify or lished with molecular markers in prior papers and 32 full uncover the parentage of grapevine cultivars. The aim of the parentages that invalidated prior results, (3) 255 full paren- present study was to undertake an extended parentage analysis tages confirming pedigrees as disclosed by the breeders and using a large sample of Vitis vinifera cultivars held in the (4) 126 full parentages that invalidated breeders’ data. Second, INRA ‘‘Domaine de Vassal’’ Grape Germplasm Repository incomplete parentages were determined in 1,087 cultivars due (France). A dataset of 2,344 unique genotypes (i.e. cultivars to the absence of complementary parents in our cultivar without synonyms, clones or mutants) identified using 20 sample. Last, a group of 276 genotypes showed no direct nSSR was analysed with FAMOZ software. Parentages relationship with any other cultivar in the collection. Com- showing a logarithm of odds score higher than 18 were vali- piling these results from the largest set of parentage data dated in relation to the historical data available. The analysis published so far both enlarges and clarifies our knowledge of first revealed the full parentage of 828 cultivars resulting in: the genetic constitution of cultivated V. -

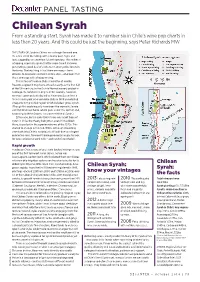

Chilean Syrah from a Standing Start, Syrah Has Made It to Number Six in Chile’S Wine Pop Charts in Less Than 20 Years

PANEL TASTING Chilean Syrah From a standing start, Syrah has made it to number six in Chile’s wine pop charts in less than 20 years. And this could be just the beginning, says Peter Richards MW The sTory of syrah in Chile is not a straightforward one. It’s a tale still in the telling, with a murky past, highs and lows, capped by an uncertain future trajectory. This makes it intriguing, especially given that for some time it has been generating a good deal of excitement among wine lovers in the know. The key thing is that there are many – from drinkers to producers and wine critics alike – who hope that this is one saga with a happy ending. The history of syrah in Chile is a matter of debate. records suggest it may have arrived as early as the first half of the 19th century, in the Quinta Normal nursery project in santiago. Its commercial origins in the country, however, are most commonly attributed to Alejandro Dussaillant, a french immigrant who arrived in Chile in 1874 and planted vineyards in the Curicó region which included ‘gross syrah’. (Though this could equally have been the aromatic savoie variety Mondeuse Noire, which goes under this epithet and, according to Wine Grapes, is a close relative of syrah.) either way, by the early 1990s there was scant trace of syrah in Chile, the theory being that, even if it had been there, it was lost in the agrarian reforms of the 1970s. This started to change in the mid-1990s. -

Red Winegrape Varieties for Long Island Vineyards

Strengthening Families & Communities • Protecting & Enhancing the Environment • Fostering Economic Development • Promoting Sustainable Agriculture Red Winegrape Varieties for Long Island Vineyards Alice Wise, Extension Educator, Viticulturist, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County February, 2013; rev. March, 2020 Contemplation of winegrape varieties is a fascinating and challenging process. We offer this list of varieties as potential alternative to the red wine varieties widely planted in the eastern U.S. – Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir. Properly sited and well-managed, these four varieties are capable of producing high quality fruit. Some regions have highlighted one of these varieties, such as Merlot and Cabernet Franc on Long Island and Cabernet Franc in the Finger Lakes. However, many industry members have expressed an interest in diversifying their vineyards. Clearly, there is room for exploration and by doing so, businesses can distinguish themselves from a marketing and stylistic viewpoint. The intent of this article is to introduce a selection of varieties that have potential for Long Island. This is by no means an exhaustive list. These suggestions merit further investigation by the winegrower. This could involve internet/print research, tasting wines from other regions and/or correspondence with fellow winegrowers. Even with a thoughtful approach, it is important to acknowledge that vine performance may vary due to site, soil type and management practices. Fruit quality and quantity will also vary from season to season. That said, a successful variety will be capable of quality fruit production despite seasonal variation in temperature and rainfall. The most prominent features of each variety are discussed based on industry experience, observations and results from the winegrape variety trial at the Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center, Riverhead, NY (cited as ‘LIHREC vineyard’). -

Vitis International Variety Catalogue Passport Data

Vitis International Variety Catalogue www.vivc.de Passport data Prime name PINOT BLANC Color of berry skin BLANC Variety number VIVC 9272 Country or region of origin of the variety FRANCE Species VITIS VINIFERA LINNÉ SUBSP. VINIFERA Pedigree as given by breeder/bibliography PINOT NOIR MUTATION Pedigree confirmed by markers Full pedigree NO Prime name of parent 1 Prime name of parent 2 Parent - offspring relationship Offspring YES Breeder Breeder institute code Breeder contact address Year of crossing Year of selection Year of protection Formation of seeds COMPLETE Sex of flowers HERMAPHRODITE Taste NONE Chlorotype A Photos of the cultivar 13 SSR-marker data YES Loci for resistance Degree of resistance YES Loci of traits Table of accession names YES Table of area YES Registered in the European Catalogue YES Links to: - Bibliography - Remarks to prime names and institute codes September 25, 2021 © Institute for Grapevine Breeding - Geilweilerhof 1 Julius Kühn-Institut Vitis International Variety Catalogue www.vivc.de Synonyms: 99 AG PINO ARBST WEISS ARNAISON BLANC ARNOISON AUVERNAS AUVERNAT AUVERNAT BLANC AUXERROIS BELI PINOT BEYAZ BURGUNDER BIELA KLEVANJKA BIJELI PINO BLANC DE CHAMPAGNE BON BLANC BORGOGNA BIANCA BORGOGNA BIANCO BORGOGNINO BORGONA BLANCO BORGONJA BELA MALA BORONJA MALO ZRNO BURGUNDA BURGUNDAC BURGUNDAC BELI BURGUNDAC BIJELI BURGUNDER BLANC BURGUNDER WEISS BURGUNDER WEISSER BURGUNDI FEHER BURGUNDI KISFEHER BURGUNDISCHE BURGUNDSKE BIELI BURGUNDSKE BILE XIMENESTRAUBE CHARDONNET PINOT BLANC CLAEVNER CLEVNER DAUNE EPINETTE EPINETTE -

European Commission

29.9.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union C 321/47 OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to the product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (2020/C 321/09) This notice is published in accordance with Article 17(5) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (1). COMMUNICATION OF A STANDARD AMENDMENT TO THE SINGLE DOCUMENT ‘VAUCLUSE’ PGI-FR-A1209-AM01 Submitted on: 2.7.2020 DESCRIPTION OF AND REASONS FOR THE APPROVED AMENDMENT 1. Description of the wine(s) Additional information on the colour of wines has been inserted in point 3.3 ‘Evaluation of the products' organoleptic characteristics’ in order to add detail to the description of the various products. The details in question have also been added to the Single Document under the heading ‘Description of the wine(s)’. 2. Geographical area Point 4.1 of Chapter I of the specification has been updated with a formal amendment to the description of the geographical area. It now specifies the year of the Geographic Code (the national reference stating municipalities per department) in listing the municipalities included in each additional geographical designation. The relevant Geographic Code is the one published in 2019. The names of some municipalities have been corrected but there has been no change to the composition of the geographical area. This amendment does not affect the Single Document. 3. Vine varieties In Chapter I(5) of the specification, the following 16 varieties have been added to those listed for the production of wines eligible for the ‘Vaucluse’ PGI: ‘Artaban N, Assyrtiko B, Cabernet Blanc B, Cabernet Cortis N, Floreal B, Monarch N, Muscaris B, Nebbiolo N, Pinotage N, Prior N, Soreli B, Souvignier Gris G, Verdejo B, Vidoc N, Voltis B and Xinomavro N.’ (1) OJ L 9, 11.1.2019, p. -

French Wine Scholar

French Wine Scholar Detailed Curriculum The French Wine Scholar™ program presents each French wine region as an integrated whole by explaining the impact of history, the significance of geological events, the importance of topographical markers and the influence of climatic factors on the wine in the the glass. No topic is discussed in isolation in order to give students a working knowledge of the material at hand. FOUNDATION UNIT: In order to launch French Wine Scholar™ candidates into the wine regions of France from a position of strength, Unit One covers French wine law, grape varieties, viticulture and winemaking in-depth. It merits reading, even by advanced students of wine, as so much has changed-- specifically with regard to wine law and new research on grape origins. ALSACE: In Alsace, the diversity of soil types, grape varieties and wine styles makes for a complicated sensory landscape. Do you know the difference between Klevner and Klevener? The relationship between Pinot Gris, Tokay and Furmint? Can you explain the difference between a Vendanges Tardives and a Sélection de Grains Nobles? This class takes Alsace beyond the basics. CHAMPAGNE: The champagne process was an evolutionary one not a revolutionary one. Find out how the method developed from an inexpert and uncontrolled phenomenon to the precise and polished process of today. Learn why Champagne is unique among the world’s sparkling wine producing regions and why it has become the world-class luxury good that it is. BOURGOGNE: In Bourgogne, an ancient and fractured geology delivers wines of distinction and distinctiveness. Learn how soil, topography and climate create enough variability to craft 101 different AOCs within this region’s borders! Discover the history and historic precedent behind such subtle and nuanced fractionalization. -

Download Tasting Notes

Retail Savings $16.99 $30.00 43% NV Jean Vullien Méthode Traditionelle Roséproduct-timed-pdf - Vin de Savoie, France - Only 40 Cases in the U.S. Why We're Drinking It In the far eastern corner of France next to the Alps sits the AOC of Vin de Savoie. Known for their own particular style and even varietals, this is an off-the-beaten-path appellation forward-looking wine lovers go to find that are particularly interesting, and typically difficult to find. Case in point, this gem here: the NV Jean Vullien Méthode Traditionelle Brut Rosé. With only 40 cases imported to the U.S., it's the definition of under-the-radar sparkling rosé that may have otherwise slipped by unnoticed had we not originally tasted it in Paris in a small, private tasting of Savoie. Crafted with a unique blend of 50% Gamay, 30% Pinot Noir, and 20% Mondeuse, it shows bubbles so fine and elegant, it literally has the palate lost – forgetting the fact it was grown outside of Champagne. Leading with a nose that features orange blossoms, candied fruit, and fresh pastries, it transcends the palate with fresh wild strawberries that play against the perfect amount of acidity. Finishing fresh and light, with a hint of ripe cherries, it leaves Sparkling lovers with the sentiment: “the greatest wines are those you don’t fine en masse”. Inside Fact: Mondeuse Noire is a red wine grape that is grown primarily in the Savoy region of France. In Savoie, the grape is used in blending with Gamay, Pinot Noir, and Poulsard where it contributes its dark color and high acid levels to the wine that allow the wines to age well.