Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics for Digital Journalists

ETHICS FOR DIGITAL JOURNALISTS The rapid growth of online media has led to new complications in journalism ethics and practice. While traditional ethical principles may not fundamentally change when information is disseminated online, applying them across platforms has become more challenging as new kinds of interactions develop between jour- nalists and audiences. In Ethics for Digital Journalists , Lawrie Zion and David Craig draw together the international expertise and experience of journalists and scholars who have all been part of the process of shaping best practices in digital journalism. Drawing on contemporary events and controversies like the Boston Marathon bombing and the Arab Spring, the authors examine emerging best practices in everything from transparency and verifi cation to aggregation, collaboration, live blogging, tweet- ing, and the challenges of digital narratives. At a time when questions of ethics and practice are challenged and subject to intense debate, this book is designed to provide students and practitioners with the insights and skills to realize their potential as professionals. Lawrie Zion is an Associate Professor of Journalism at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, and editor-in-chief of the online magazine upstart. He has worked as a broadcaster with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and as a fi lm journalist for a range of print publications. He wrote and researched the 2007 documentary The Sounds of Aus , which tells the story of the Australian accent. David Craig is a Professor of Journalism and Associate Dean at the University of Oklahoma in the United States. A former newspaper copy editor, he is the author of Excellence in Online Journalism: Exploring Current Practices in an Evolving Environ- ment and The Ethics of the Story: Using Narrative Techniques Responsibly in Journalism . -

The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe

MIT 2002 The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe Martha Stone, Jan Bierhoff Introduction The media landscape worldwide is changing rapidly. In the 1980s, the “traditional” mass media players were in control: TV, newspapers and radio. Newspaper readers consumed the paper at a specified time of the day, in the morning, over breakfast or after work. Radio was listened to on the way to and from work. Television news was watched in the morning mid-day and/or evening. Fast forward to 2002, and the media landscape is fragmented. The consumption of news has changed dramatically. News information is all around, on mobile phones, newspapers, PDAs, TV, Interactive TV, cable, Internet, teletext, kiosks, radio, video screens in hotel elevators, video programming for airlines and much more. Meanwhile, also the concept of news has changed to be more personalised, more service-oriented and less institutional. The sweeping market changes have forced media companies to adapt. This new challenge explains why Dow Jones Company, owner of the Wall Street Journal, now considers itself “a news provider of any news, all the time, everywhere.” In the frame of the MUDIA project (see annex 1), an international team of researchers has taken stock of the present situation concerning media and newsroom convergence in Europe. The various routes taken to this ideal have been mapped in a number of case studies. In total 24 leading European media (newspapers, broadcasters, netnative newscasters) were approached with a comprehensive questionnaire and later visited to interview key representatives of the editorial and commercial departments (see annex 2). The study zoomed in on four countries: the United Kingdom, Spain, France and Sweden; viewpoints from other media elsewhere in Europe were added on the basis of existing literature, and throughout the study a comparison with the USA is made where possible and relevant. -

Spring 2019 Umass Journalism Courses Confirm Classes, Time and Location on SPIRE

Spring 2019 UMass Journalism Courses Confirm classes, time and location on SPIRE. This is a guide, and courses may change. Journal 201: Introduction to Journalism (4 cr.) Cap. 100 Open to first-year and sophomores of any major. Gen Ed: SB DU TTH 8:30 a.m. - 9:45 a.m. Sibii ILC S140 Introduction to Journalism is a survey class that covers the basic principles and practices of contemporary journalism. By studying fundamentals like truth telling, fact checking, the First Amendment, diversity, being a watchdog to the powerful and public engagement, students will explore the best of what journalists do in a democratic society. Students will also assess changes in the production, distribution, and consumption of journalism as new technologies are introduced to newsrooms. Toward the end of the semester, students look at case studies across the media and learn how different audiences, mediums, and perspectives affect the news. Journal 250: News Literacy (4 cr.) Cap. 40 Open to any major. Gen Ed: SB TTh 10:00 a.m. - 11:15 a.m. Fox ILC N255 What is fact? What is fiction? Can we even tell the difference anymore? Today’s 24-hour news environment is saturated with a wide array of sources ranging from real-time citizen journalism reports, government propaganda and corporate spin to real-time blogging, photos, and videos from around the world, as well as reports from the mainstream media. In this class, students will become more discerning consumers of news. Students will use critical-thinking skills to develop the tools needed to determine what news sources are reliable in the digital world. -

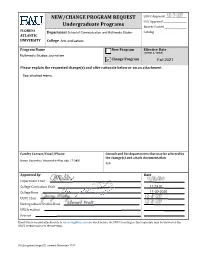

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST Undergraduate Programs

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST UUPC Approval _________________ UFS Approval ___________________ Undergraduate Programs Banner Posted __________________ FLORIDA Department School of Communication and Multimedia Studies Catalog __________________________ ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY College Arts and Letters Program Name New Program Effective Date (TERM & YEAR) Multimedia Studies Journalism ✔ Change Program Fall 2021 Please explain the requested change(s) and offer rationale below or on an attachment See attached memo. Faculty Contact/Email/Phone Consult and list departments that may be affected by the change(s) and attach documentation Aaron Veenstra / [email protected] / 7-3851 N/A Approved by Date Department Chair College Curriculum Chair 11.23.20 College Dean 11-30-2020 UUPC Chair Undergraduate Studies Dean UFS President Provost Email this form and attachments to [email protected] one week before the UUPC meeting so that materials may be viewed on the UUPC website prior to the meeting. FAUprogramchangeUG, created December 2017 Memo for Multimedia Journalism Program Changes: 1. In an effort the streamline the curriculum, decrease time to degree, and maintain curricular rigor, the MMSJ program proposes several changes. We will reduce the required number of credits from 50 credits to a minimum of 38 (can be more depending on focus courses selected). 2. We are also dividing the MMSJ Curriculum into three parallel streams: Core (13 required credits), Production (13 required credits), Focus (12 required credits minimum). This entails renaming: a. the “Disciplinary Core” into “Core,” b. renaming the “Performance and Production” category to “Production” and, c. remove/collapse all remaining current sections, Focus, Theory/History/Criticism, and Performance and Production Emphasis”, to “Focus” resulting the categories as listed below: Core The following courses are required (13 credits): MMC 1540 Introduction to Multimedia Studies (3 credits) JOU 4004 U.S. -

University of Calicut Board of Studies (Ug) In

[Type text] UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT BOARD OF STUDIES (UG) IN JOURNALISM Restructured Curriculum and Syllabi as per CBCSSUG Regulations 2019 (2019 Admission Onwards) PART I B.A. Journalism and Mass Communication PART II Complementary Courses in 1. Journalism, 2. Electronic Media 3. Mass Communication (for BA West Asian Studies) 4. Complementary Courses in Media Practices for B.A LRP Programmes in Visual Communication, Multimedia, and Film and Television for Non-Journalism UG Programmes [Type text] GENERAL SCHEME OF THE PROGRAMME Sl No Course No of Courses Credits 1 Common Courses (English) 6 22 2 Common Courses (Additional Language) 4 16 3 Core Courses 15 61 4 Project (Linked to Core Courses) 1 2 5 Complementary Courses 2 16 6 Open Courses 1 3 Total 120 Audit course 4 16 Extra Credit Course 1 4 Total 140 [Type text] PART I B.A. JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Distribution of Courses A - Common Courses B - Core Courses C - Complementary Courses D - Open Courses Ability Enhancement Course/Audit Course Extra Credit Activities [Type text] A. Common Courses Sl. No. Code Title Semester 1 A01 Common English Course I I 2 A02 Common English Course II I 3 A03 Common English Course III II 4 A04 Common English Course IV II 5 A05 Common English Course V III 6 A06 Common English Course VI IV 7 A07 Additional language Course I I 8 A08 Additional language Course II II 9 A09 Additional language Course III III 10 A10 Additional language Course IV IV Total Credit 38 [Type text] B. Core Courses Sl. No. Code Title Contact hrs Credit Semester 11 JOU1B01 Fundamentals -

What Drives Hyper-Partisan News Sharing: Exploring the Role of Source, Style, and Content

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Department Faculty Publication Series Communication 2020 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content Weiai Wayne Xu Yoonmo Sang Christopher Kim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_faculty_pubs 1 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content Weiai Wayne Xu Assistant Professor N334 Integrative Learning Center, Department of Communication University of Massachusetts – Amherst Amherst, MA 01003-1100 Phone: +001-(414)688-3059 Email: [email protected] Yoonmo Sang Assistant Professor Faculty of Arts & Design University of Canberra Email: [email protected] Christopher Kim Ph.D. Candidate Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra Email: [email protected] 2 A growing number of hyper-partisan alternative media outlets have sprung up online to challenge mainstream journalism. However, research on news sharing in this particular media environment is lacking. Based on the virality of sixteen partisan outlets’ coverage of immigration and using the latest computational linguistic algorithm, the present study probes how hyper- partisan news sharing is related to source transparency, content styles, and moral framing. The study finds that the most shared articles reveal author names, but not necessarily other types of author information. The study uncovers a salient link between moral frames and virality. In particular, audiences are more sensitive to moral frames that emphasize authority/respect, fairness/reciprocity, and harm/care. Keywords: news sharing, news diffusion, partisan media, Facebook, social media, moral framing, moral foundations theory 3 What drives hyper-partisan news sharing: Exploring the role of source, style, and content The 2016 U.S. -

Journalism (JOUR) 1

Journalism (JOUR) 1 JOUR 2712. Intermediate Print Reporting. (4 Credits) JOURNALISM (JOUR) This is an intermediate reporting course which focuses on developing investigative skills through the use of human sources and computer- JOUR 1701. Introduction to Multimedia Journalism With Lab. (4 Credits) assisted reporting. Students will develop beat reporting skills, source- A course designed to introduce the student to various fundamentals building and journalism ethics. Students will gather and report on actual of journalism today, including writing leads; finding and interviewing news events in New York City. Four-credit courses that meet for 150 sources; document, database and digital research; and story minutes per week require three additional hours of class preparation per development and packaging. The course also discusses the intersection week on the part of the student in lieu of an additional hour of formal of journalism with broader social contexts and questions, exploring the instruction. changing nature of news, the shifting social role of the press and the Attribute: JWRI. evolving ethical and legal issues affecting the field. The course requires a JOUR 2714. Radio and Audio Reporting. (4 Credits) once weekly tools lab, which introduces essential photo, audio, and video A survey of the historical styles, formats and genres that have been used editing software for digital and multimedia work. This class is approved for radio, comparing these to contemporary formats used for commercial to count as an EP1 seminar for first-year students; students need to and noncommercial stations, analyzing the effects that technological, contact their class dean to have the attribute applied. Note: Credit will not social and regulatory changes have had on the medium. -

Journalism (JOUR) San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021

Journalism (JOUR) San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021 JOUR 300GW Reporting - GWAR (Units: 3) JOURNALISM (JOUR) Prerequisites: Restricted to upper-division Journalism majors and minors; GE Area A2; JOUR 205* and JOUR 221* or equivalents with grades of C or JOUR 205 Social Impact of Journalism (Units: 3) better. History, organization, social role and function of journalism. A grade of C or better required for Journalism majors and minors. Advanced concepts of news gathering, interviewing, and writing. Cover Course Attributes: San Francisco and Oakland neighborhoods. A grade of C or better is required for Journalism majors and minors. (ABC/NC grading only) • C2: Humanities Course Attributes: JOUR 221 Newswriting (Units: 3) • Graduation Writing Assessment Prerequisites: GE Areas A2 and A3. Typing speed of 25 wpm or better. JOUR 304 Cultural Diversity and News Media (Units: 3) Development of news judgment and clear writing skills. A grade of C or Prerequisites: Restricted to upper-division standing; GE Area A2*. better required for Journalism majors and minors. (Plus-minus letter grade only) Exploration of how the practice of newsgathering influences social reality. Exploration of issues facing U.S. news media as they struggle to JOUR 222 Newswriting Lab (Unit: 1) understand an increasingly diverse society. Historical overview of the Prerequisites: GE Areas A2 and A3. problem and discussion on current obstacles facing journalists' efforts to Associated Press style writing, English grammar, and punctuation. A improve coverage and newsroom representation. A grade of C or better grade of C or better required for Journalism majors and minors. (Plus- required for Journalism majors and minors. -

Multimedia Journalism Brochure

WESTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Multimedia Journalism Department of Broadcasting & Journalism, College of Fine Arts & Communication Program of Study The Department of Broadcasting and Journalism offers a Bachelor of Arts in Broadcasting and Journalism. The curriculum is designed to provide a comprehensive program for students wanting to work in today’s media. All of our students have a foundation in basic media history, production, and delivery before focusing in sports broadcasting, multimedia journalism, broadcast production, and advertising/public relations. They also receive valuable hands-on experience and mentorship in our program. Students produce programming for ESPN and wiutv3 using state-of-the-art, high-definition television facilities and operate an FM broadcast station, WIUS. Graduates of the program enter various careers in television, radio, sports broadcasting, advertising, public relations and post-production operations, including directing, producing, reporting, on-air talent programming, sales, advertising, sports and post-production. Our students are winning state, regional and national competitions and receiving important recognition that separates them from others seeking internships and jobs. Multimedia Journalism The multimedia journalism option prepares students for careers in all aspects of news production. Our students learn to tell stories and report information that will be distributed on multiple platforms. Students can apply their skills to our student-produced newscast, NEWS3. Students will learn to interview newsmakers, gather audio and video footage, edit news reports and produce half-hour live television newscasts that reach Macomb and McDonough County viewers. Students can apply to work at the award-winning NPR affiliate located on the WIU campus, Tri States Public Radio. Students will also learn to write for print and digital-based media. -

Public Media Journalism

Public Media Journalism With its enduring reputation as a trusted source of high-quality journalism, public media is a major source of fact-based news, meeting the information needs of communities across the country. As steward of the federal appropriation for public media, CPB supports multimedia journalism that is fair, accurate, balanced, objective, and transparent, and created in a manner consistent with local stations’ and producers’ editorial independence. In addition to supporting more than 1,500 public media stations across the country, CPB seeks to increase the capacity of public media to create diverse, high-quality and engaging journalism by supporting public media collaborations. CPB supports initiatives such as America Amplified, a public media collaborative network producing innovative journalism from community engagement efforts, and Every 30 Seconds, a public media collaboration among PRX’s “The World” and public radio stations to track the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond. CPB also supports national news organizations including PBS NewsHour, which launched NewsHour West in Phoenix in 2019; FRONTLINE, which is developing investigative journalism projects with local news organizations through the Local Journalism Project; and NPR, which maintains its 17 international bureaus with CPB support. CPB has supported public media journalism collaborations since 2009 to add editorial staff, encourage pooled coverage and other efficiencies, and support enterprise reporting. They have helped develop a collaborative culture to strengthen local journalism across the public media system. Journalism Collaborations Through years of strategic focus on digital innovation, diversity and dialogue, CPB has cultivated a network of local and regional public media news organizations that, in partnership with national producers, strengthens public media’s role as a trusted and relevant news source. -

Inside the Changing Newsroom: Journalists' Responses to Media

Inside the changing newsroom: journalists’ responses to media convergence Konstantinos Saltzis Department of Media and Cultural Production, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK [email protected] Roger Dickinson Department of Media and Communication, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK [email protected] Abstract Purpose - This article reports on research conducted inside British national media organizations. Interviews were conducted with journalists working in newsrooms at the BBC, Sky News, The Guardian and the Financial Times. The research was designed to investigate the impact on the working practices of journalists of the process of production convergence – the trend towards news reporting in more than one medium in formerly single-medium organizations. The article describes the changes that are taking place and the ways journalists are reacting to them. Methodology/approach - Interviews were conducted with 20 journalists during 2002 and 2003. Findings - The data shows that while multimedia news is becoming well-established, the multimedia journalist has been slow to arrive. This is because of the pressures that multi-media working add to the journalist’s daily routine and a concern over the impact on the quality of output. Research limitations/implications - The media environment is evolving rapidly and research findings on this topic quickly go out of date, but the findings presented here offer valuable insights into the news production processes operating in British national media organizations and the ways journalists are adapting to, and are likely to continue to adapt to, changes in production technologies and changed systems of working. Originality/value - The research reported here is the first to focus on journalistic practice in a converging media environment. -

FUTURE ACTION ITEM #1 Establishment of Murrow College of Communication Departments (Daniel J

FUTURE ACTION ITEM #1 Establishment of Murrow College of Communication Departments (Daniel J. Bernardo) TO ALL MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS SUBJECT: Establishment of Edward R. Murrow College of Communication Departments PROPOSED: That the Board of Regents establish the following three departments within the Edward R. Murrow College of Communication: • Department of Journalism and Media Production • Department of Communication and Society • Department of Strategic Communication SUBMITTED BY: Daniel J. Bernardo, Provost and Executive Vice President SUPPORTING INFORMATION: Recently, the Murrow College of Communication requested, and received approval by the WSU Board of Regents and Faculty Senate, to realign degree plans and degree names. The Bachelor of Arts in Communication has been renamed as separate degrees in Journalism and Media Production, Communication and Society, and Strategic Communication. These changes were requested for the following beneficial reasons: 1. Differentiation between degrees: The three degrees (which were identical to the current three Majors) shared only 13 credits, including college pre-requisites, a one credit orientation course and six credits of college core courses. Thus, each degree contained additional credits (24-30) unique to each degree. 2. Accreditation: The College intends to pursue accreditation from the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (ACEJMC). Dividing the communication degree into three separate degrees improved its ability to achieve accreditation by seeking accreditation for only Strategic Communication and Journalism and Media Production. Communication and Society falls outside the parameters of ACEJMC as an accrediting body. 3. Industry demand: The previous degree designation of “communication” was generally applied to programs that offer a theoretically focused approach to the field of communication and Research and Academic Affairs Committee R-4 January 26-27, 2017 Page 1 of 3 its impact on society.