What Drives Hyper-Partisan News Sharing: Exploring the Role of Source, Style, and Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics for Digital Journalists

ETHICS FOR DIGITAL JOURNALISTS The rapid growth of online media has led to new complications in journalism ethics and practice. While traditional ethical principles may not fundamentally change when information is disseminated online, applying them across platforms has become more challenging as new kinds of interactions develop between jour- nalists and audiences. In Ethics for Digital Journalists , Lawrie Zion and David Craig draw together the international expertise and experience of journalists and scholars who have all been part of the process of shaping best practices in digital journalism. Drawing on contemporary events and controversies like the Boston Marathon bombing and the Arab Spring, the authors examine emerging best practices in everything from transparency and verifi cation to aggregation, collaboration, live blogging, tweet- ing, and the challenges of digital narratives. At a time when questions of ethics and practice are challenged and subject to intense debate, this book is designed to provide students and practitioners with the insights and skills to realize their potential as professionals. Lawrie Zion is an Associate Professor of Journalism at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, and editor-in-chief of the online magazine upstart. He has worked as a broadcaster with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and as a fi lm journalist for a range of print publications. He wrote and researched the 2007 documentary The Sounds of Aus , which tells the story of the Australian accent. David Craig is a Professor of Journalism and Associate Dean at the University of Oklahoma in the United States. A former newspaper copy editor, he is the author of Excellence in Online Journalism: Exploring Current Practices in an Evolving Environ- ment and The Ethics of the Story: Using Narrative Techniques Responsibly in Journalism . -

The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe

MIT 2002 The State of Multimedia Newsrooms in Europe Martha Stone, Jan Bierhoff Introduction The media landscape worldwide is changing rapidly. In the 1980s, the “traditional” mass media players were in control: TV, newspapers and radio. Newspaper readers consumed the paper at a specified time of the day, in the morning, over breakfast or after work. Radio was listened to on the way to and from work. Television news was watched in the morning mid-day and/or evening. Fast forward to 2002, and the media landscape is fragmented. The consumption of news has changed dramatically. News information is all around, on mobile phones, newspapers, PDAs, TV, Interactive TV, cable, Internet, teletext, kiosks, radio, video screens in hotel elevators, video programming for airlines and much more. Meanwhile, also the concept of news has changed to be more personalised, more service-oriented and less institutional. The sweeping market changes have forced media companies to adapt. This new challenge explains why Dow Jones Company, owner of the Wall Street Journal, now considers itself “a news provider of any news, all the time, everywhere.” In the frame of the MUDIA project (see annex 1), an international team of researchers has taken stock of the present situation concerning media and newsroom convergence in Europe. The various routes taken to this ideal have been mapped in a number of case studies. In total 24 leading European media (newspapers, broadcasters, netnative newscasters) were approached with a comprehensive questionnaire and later visited to interview key representatives of the editorial and commercial departments (see annex 2). The study zoomed in on four countries: the United Kingdom, Spain, France and Sweden; viewpoints from other media elsewhere in Europe were added on the basis of existing literature, and throughout the study a comparison with the USA is made where possible and relevant. -

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Taking Down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, Not Collaboration, Please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017

Taking down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, not collaboration, please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017 In the US there are already effective Trump boycotts seeking to delegitimise his political agenda. Internationally, protesters will be out wherever he goes. And from Africa, there are sound arguments to play a catalytic role, mainly because the most serious threat to humanity and environment is Trump’s climate change denialism. Consider two contrasting strategies to deal with the latest mutation of US imperialism: we should protest Donald Trump and Trumpism at every opportunity as a way to contribute to the unity of the world’s oppressed people, and now more urgently link our intersectional struggles; or we should somehow take advantage of his presidency to promote the interests of the ‘left’ or the ‘Global South’ where there is overlap in weakening Washington’s grip (such as in questioning exploitative world trading regimes). The latter position is now rare indeed, although before the election Hillary Clinton’s commitment to militaristic neoliberalism generated so much opposition that to some, the anticipated ‘paleo-conservatism’ of an isolationist-minded Trump appeared attractive. One international analyst of great reknown, Boris Kagarlitsky, makes this same argument this week largely because Trump is questioning pro-corporate ‘free trade’ deals. But the argument for selective cooperation with Trump was best articulated in Pambazuka as part of a series of otherwise compelling reflections by the Ugandan writer and former South Centre director Yash Tandon. Tandon might re-examine the ‘space’ he can ‘seize’ with Trump, the ‘fraud’ Since more than any other individual Tandon helped make the 1999 Seattle and Cancun World Trade Organisation summits a profound disaster for world elites, I take him very seriously. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Spring 2019 Umass Journalism Courses Confirm Classes, Time and Location on SPIRE

Spring 2019 UMass Journalism Courses Confirm classes, time and location on SPIRE. This is a guide, and courses may change. Journal 201: Introduction to Journalism (4 cr.) Cap. 100 Open to first-year and sophomores of any major. Gen Ed: SB DU TTH 8:30 a.m. - 9:45 a.m. Sibii ILC S140 Introduction to Journalism is a survey class that covers the basic principles and practices of contemporary journalism. By studying fundamentals like truth telling, fact checking, the First Amendment, diversity, being a watchdog to the powerful and public engagement, students will explore the best of what journalists do in a democratic society. Students will also assess changes in the production, distribution, and consumption of journalism as new technologies are introduced to newsrooms. Toward the end of the semester, students look at case studies across the media and learn how different audiences, mediums, and perspectives affect the news. Journal 250: News Literacy (4 cr.) Cap. 40 Open to any major. Gen Ed: SB TTh 10:00 a.m. - 11:15 a.m. Fox ILC N255 What is fact? What is fiction? Can we even tell the difference anymore? Today’s 24-hour news environment is saturated with a wide array of sources ranging from real-time citizen journalism reports, government propaganda and corporate spin to real-time blogging, photos, and videos from around the world, as well as reports from the mainstream media. In this class, students will become more discerning consumers of news. Students will use critical-thinking skills to develop the tools needed to determine what news sources are reliable in the digital world. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Trumpism on College Campuses

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Trumpism on College Campuses Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1d51s5hk Journal QUALITATIVE SOCIOLOGY, 43(2) ISSN 0162-0436 Authors Kidder, Jeffrey L Binder, Amy J Publication Date 2020-06-01 DOI 10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Qualitative Sociology (2020) 43:145–163 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-020-09446-z Trumpism on College Campuses Jeffrey L. Kidder1 & Amy J. Binder 2 Published online: 1 February 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract In this paper, we report data from interviews with members of conservative political clubs at four flagship public universities. First, we categorize these students into three analytically distinct orientations regarding Donald Trump and his presidency (or what we call Trumpism). There are principled rejecters, true believers, and satisficed partisans. We argue that Trumpism is a disunifying symbol in our respondents’ self- narratives. Specifically, right-leaning collegians use Trumpism to draw distinctions over the appropriate meaning of conservatism. Second, we show how political clubs sort and shape orientations to Trumpism. As such, our work reveals how student-led groups can play a significant role in making different political discourses available on campuses and shaping the types of activism pursued by club members—both of which have potentially serious implications for the content and character of American democracy moving forward. Keywords Americanpolitics.Conservatism.Culture.Highereducation.Identity.Organizations Introduction Donald Trump, first as a candidate and now as the president, has been an exceptionally divisive force in American politics, even among conservatives who typically vote Republican. -

Citizen Breitbart Polarizing and Profane, Andrew Breitbart Is Fast Becoming the Most Powerful Right-Wing Force on the Web by STEVE ONEY

´+$>&!7¨ ´+$>&!7¨ PROFILE Citizen Breitbart Polarizing and profane, Andrew Breitbart is fast becoming the most powerful right-wing force on the Web BY STEVE ONEY ndrew breitbart sits in an Aeron chair at an iMac com- puter gazing out the sliding glass door of his Los Angeles home office. On the patio, a hulaA hoop and a portable basketball rim await his children’s return from school. Breitbart, 41, dressed on this late-winter day in his standard work uniform of a dirty oxford-cloth shirt and grungy khaki shorts, looks more like a surf bum than one of the most divisive figures in Amer- ica’s political and culture wars. Then his BlackBerry rings. The woman at the other end of the line, conservative fulminator Ann Coulter, is among Breitbart’s staunchest allies, and they soon are engaged in a spirited at- tack on liberals. “Their entire structure is writhing in diseased agony on the side of the road, and they don’t even realize it,” Breitbart says. But the left isn’t the only object of disdain. “I’m sick of this effete GOP nothing sandwich,” he adds, grow- ing more animated. “As long as everyone is so pristine and socially registered, we’re going to lose.” Shortly before signing off, Breitbart says, “The second I realized I liked being hated more than I liked being liked—that’s when the game began.” It’s a game he plays extraordinarily well. Breitbart has become the Web’s most com- bative conservative impresario—part new- media mogul, part Barnumesque scamp. -

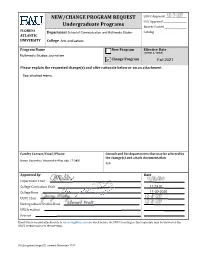

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST Undergraduate Programs

NEW/CHANGE PROGRAM REQUEST UUPC Approval _________________ UFS Approval ___________________ Undergraduate Programs Banner Posted __________________ FLORIDA Department School of Communication and Multimedia Studies Catalog __________________________ ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY College Arts and Letters Program Name New Program Effective Date (TERM & YEAR) Multimedia Studies Journalism ✔ Change Program Fall 2021 Please explain the requested change(s) and offer rationale below or on an attachment See attached memo. Faculty Contact/Email/Phone Consult and list departments that may be affected by the change(s) and attach documentation Aaron Veenstra / [email protected] / 7-3851 N/A Approved by Date Department Chair College Curriculum Chair 11.23.20 College Dean 11-30-2020 UUPC Chair Undergraduate Studies Dean UFS President Provost Email this form and attachments to [email protected] one week before the UUPC meeting so that materials may be viewed on the UUPC website prior to the meeting. FAUprogramchangeUG, created December 2017 Memo for Multimedia Journalism Program Changes: 1. In an effort the streamline the curriculum, decrease time to degree, and maintain curricular rigor, the MMSJ program proposes several changes. We will reduce the required number of credits from 50 credits to a minimum of 38 (can be more depending on focus courses selected). 2. We are also dividing the MMSJ Curriculum into three parallel streams: Core (13 required credits), Production (13 required credits), Focus (12 required credits minimum). This entails renaming: a. the “Disciplinary Core” into “Core,” b. renaming the “Performance and Production” category to “Production” and, c. remove/collapse all remaining current sections, Focus, Theory/History/Criticism, and Performance and Production Emphasis”, to “Focus” resulting the categories as listed below: Core The following courses are required (13 credits): MMC 1540 Introduction to Multimedia Studies (3 credits) JOU 4004 U.S. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

University of Calicut Board of Studies (Ug) In

[Type text] UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT BOARD OF STUDIES (UG) IN JOURNALISM Restructured Curriculum and Syllabi as per CBCSSUG Regulations 2019 (2019 Admission Onwards) PART I B.A. Journalism and Mass Communication PART II Complementary Courses in 1. Journalism, 2. Electronic Media 3. Mass Communication (for BA West Asian Studies) 4. Complementary Courses in Media Practices for B.A LRP Programmes in Visual Communication, Multimedia, and Film and Television for Non-Journalism UG Programmes [Type text] GENERAL SCHEME OF THE PROGRAMME Sl No Course No of Courses Credits 1 Common Courses (English) 6 22 2 Common Courses (Additional Language) 4 16 3 Core Courses 15 61 4 Project (Linked to Core Courses) 1 2 5 Complementary Courses 2 16 6 Open Courses 1 3 Total 120 Audit course 4 16 Extra Credit Course 1 4 Total 140 [Type text] PART I B.A. JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION Distribution of Courses A - Common Courses B - Core Courses C - Complementary Courses D - Open Courses Ability Enhancement Course/Audit Course Extra Credit Activities [Type text] A. Common Courses Sl. No. Code Title Semester 1 A01 Common English Course I I 2 A02 Common English Course II I 3 A03 Common English Course III II 4 A04 Common English Course IV II 5 A05 Common English Course V III 6 A06 Common English Course VI IV 7 A07 Additional language Course I I 8 A08 Additional language Course II II 9 A09 Additional language Course III III 10 A10 Additional language Course IV IV Total Credit 38 [Type text] B. Core Courses Sl. No. Code Title Contact hrs Credit Semester 11 JOU1B01 Fundamentals