Minoru Yamasaki Interview, [Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan's Historic Preservation Plan

Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Governor Rick Snyder Kevin Elsenheimer, Executive Director, Michigan State Housing Development Authority Brian D. Conway, State Historic Preservation Officer Written by Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner, Michigan State Historic Preservation Office with assistance from Alan Levy and Kristine Kidorf Goaltrac, Inc. For more information on Michigan’s historic preservation programs visit michigan.gov/SHPo. The National Park Service (NPS), U. S. Department of the Interior, requires each State Historic Preservation Office to develop and publish a statewide historic preservation plan every five years. (Historic Preservation Fund Grants Manual, Chapter 6, Section G) As required by NPS, Michigan’s Five-Year Historic Preservation Plan was developed with public input. The contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. The activity that is the subject of this project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. However, the contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilita- tion Act of 1973 and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. -

Challenges and Achievements

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture NISEI ARCHITECTS: CHALLENGES AND ACHIEVEMENTS A Thesis in Architecture by Katrin Freude © 2017 Katrin Freude Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture May 2017 The Thesis of Katrin Freude was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alexandra Staub Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Advisor Denise Costanzo Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Co-Advisor Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Architecture Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History Ute Poerschke Associate Professor of Architecture Director of Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Japanese-Americans and their culture have been perceived very ambivalently in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century; while they mostly faced discrimination for their ethnicity by the white majority in the United States, there has also been a consistent group of admirers of the Japanese art and architecture. Nisei (Japanese-Americans of the second generation) architects inherited the racial stigma of the Japanese minority but increasingly benefited from the new aesthetic light that was cast, in both pre- and post-war years, on Japanese art and architecture. This thesis aims to clarify how Nisei architects dealt with this ambivalence and how it was mirrored in their professional lives and their built designs. How did architects, operating in the United States, perceive Japanese architecture? How did these perceptions affect their designs? I aim to clarify these influences through case studies that will include such general issues as (1) Japanese-Americans’ general cultural evolution, (2) architects operating in the United States and their relation to Japanese architecture, and (3) biographies of three Nisei architects: George Nakashima, Minoru Yamasaki, and George Matsumoto. -

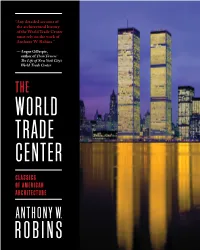

To Read Sample Pages

“ Any detailed account of the architectural history of the World Trade Center must rely on the work of Anthony W. Robins.” — Angus Gillespie, author of Twin Towers: Th e Life of New York City’s World Trade Center THE WORLD TRADE CENTER CLASSICS OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE ANTHONY W. ROBINS Originally published in 1987 while the Twin Towers still stood — brash and controversial, a new symbol of the city and the country — this book off ered the fi rst serious con- sideration of the planning and design of the World Trade Center. It benefi ted from interviews with fi gures still on the scene, and archival documents still available for study. Many of those interviewed, and many of the documents, are gone. But even if they remained available today, it would be impossible now to write this book from the same perspective. Too much has happened here. In this, the tenth anniversary year of the disaster, a new World Trade Center is rising on the site. We can fi nally begin to imagine life returning, with thousands of people streaming into the new build- ings to work or conduct business, and thousands more, from all over the world, coming to visit the new memorial. It is only natural, then, that we will fi nd ourselves thinking about what life was like in the original Center. Th is new edition of the book — expanded to include copies of some of the documents upon which the text was based — is off ered as a memory of the World Trade Center as it once was. -

Modelsurvivor

CG Spring 04Fn5.cc 2/24/04 11:59 AM Page 10 GRANT SPOTLIGHT MODEL SURVIVOR Restoring an Architect’s Miniature Masterwork Though a prominent part of New York’s skyline—and a symbol of the city itself—the THE RESTORATION Twin Towers were originally viewed with skepticism. To win over the skeptics, architect WAS LED BY A MODEL Minoru Yamasaki expressed his vision with an elaborately detailed model, today the only MAKER WITH surviving three-dimensional representation of the World Trade Center. CONSERVATION The events of September 11, 2001, have imbued the model with significance that its creators could EXPERTISE AND THE never have imagined. Now part of the American Architectural Foundation’s prints and drawings col- FORMER CHIEF OF lection, the model has undergone a complete restoration thanks to the congressionally funded Save YAMASAKI’S MODEL America’s Treasures grant program of the National Park Service. SHOP, WHOSE The model was donated to the foundation’s collection in 1992, but little is known about its travels KNOWLEDGE OF THE over the past 30 years. What was immediately evident was the urgent need to arrest its worsening con- FIRM’S TECHNIQUES dition. The model is seven feet tall and eight by ten feet at its base; its size, weight, and difficult assem- bly (three hours minimum) did not work in its favor. FOR MODEL-BUILDING “An intriguing and complex period piece in very fragile condition,” is how the foundation described AT THE TIME WAS it. Delicate by nature, architectural models are easily damaged. Often kept in less-than-ideal condi- INVALUABLE. -

Blue Cross Likes That Mutual Feeling

20150309-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 3/6/2015 5:50 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 31, No. 10 MARCH 9 – 15, 2015 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2015 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved One year into life LOOKING BACK Minoru Page 3 as a nonprofit Yamasaki was hired mutual, to design Brookfield Office Honigman hires Carl Levin expect more to design Brookfield Office change, Blue Cross Park, a high-end complex to advise on government CEO Loepp in Farmington Hills says. At Roush Industries, theme park biz ups, downs are OK likes that 2 Cobo events allow young innovators to see the D CRAIN’S MICHIGAN BUSINESS COURTESY OF BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD OF MICHIGAN mutual feeling Hotel demand raises supply – that’s good, maybe, Page 15 has garnered more than Insurer uses its 100,000 subscribers and ar- guably forced competitors to lower prices. new nonprofit “We have the opportu- nity to grow nationally as we are now a nonprofit mutual status to mutual,” Loepp said. “We are in a spot where we are COURTESY OF ETKIN LLC looking” at possible in- Brookfield Office Park (above) was one of the final chart growth works of Minoru Yamasaki but one of many local Loepp vestments in health com- buildings he designed, including Temple Beth El. BY JAY GREENE panies or joint ventures CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS with other Blues plans, he said. For example, Loepp said, the Accident Fund Dan Loepp says there have been many Insurance Co. of America, a Blue Cross for- changes at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan profit subsidiary that sells workers’ com- The new Crainsdetroit.com: during its first full year as a nonprofit mutu- pensation insurance, “now has the ability to Yamasaki’s al health insurance company. -

Symbolism and the City: from Towers of Power to 'Ground Zero'

Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays (Vol: 15) Symbolism and the city: From towers of power to ‘Ground Zero’ Robert Patrick University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada Amy MacDonald University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Canada Abstract This paper explores the symbolism of New York City’s World Trade Center (WTC) before and after the devastating attack of September 11, 2001. The many metaphors captured in the built space of the WTC site are interrogated from ‘Ground Zero’ to the symbolic significance of the new ‘Freedom Tower’ now nearing completion (2014). In fulfilling the intended symbolism of American economic power, the WTC towers became pop-culture symbols of New York City, and the Unit- ed States. The WTC towers stood as twin icons of western economic dominance along with ‘Wall Street’ and ‘Dow Jones’ reflecting the American ethos of freedom and opportunity. However, the WTC also imbued negative, albeit unintended, symbolism such as the coldness of modernist architecture, social class disparities across urban America, and global domina- tion. Plans for redeveloping the WTC site predominantly highlight the intended positive symbolic connotations of the for- mer Twin Towers, including freedom and opportunity. This article points to the symbolic significance of urban built form and the potential negative consequences that are associated with iconic structures, including the new Freedom Tower. Keywords: symbolism, iconic architecture, New York City, World Trade Center Introduction tions leading to positive and negative actions of individuals and On September 11, 2001 a terrorist attack of horrific propor- groups. Indeed, there is a long fascination among geographers tions destroyed the New York World Trade Center and surround- and planners to the symbolic functions of ‘architectural gigan- ing structures. -

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71St Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71st Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Saint Paul, Minnesota, 18–22 April 2018 All Ado About Bomarzo Architecture of Diplomacy and Defense Anatole Tchikine, Dumbarton Oaks, USA, Session Chair Cynthia G. Falk, State University of New York at Oneonta, USA, and Lisa P. Davidson, HABS—National Park Service, USA, “Landscape Architecture without Architects: Bomarzo and the Vernac- Session Co-Chairs ular,” Katherine Coty, University of Washington, USA “Cannibals, Grottoes and Vicino Orsini’s Sacro Bosco,” Luke Mor- “Building and Abandoning U.S. Naval Station Tutuila,” Kelema gan, Monash University, Australia Moses, Occidental College, USA “Botanicals and Symbolism in the Landscape of Bomarzo,” John “Border Stakes: Architecture as Diplomatic Tool in Contested Inter- Garton, Clark University, USA war Italo-Yugoslav Territories,” Matthew Worsnick, Institute of “‘Impressions so alien’: The Postwar Afterlife of the Sacro Fine Arts (NYU), USA Bosco,” Thalia Allington-Wood, University College “Architectural Mechanism of the Frontier Villages at the Korean London, UK Border,” Alex Young Il Seo, University of Cambridge, UK “Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden and the Legacies of Bomarzo,” “The Architecture of Peace in the Middle East,” Neta Feniger, John Beardsley, Dumbarton Oaks, USA Te c h n i o n —Israel Institute of Technology The Architecture of Commercial Networks, 1500–1900 Life to Architecture: Uncovering Women’s Narratives Katie Jakobiec, University of Oxford, -

APC WTC Thesis V8 090724

A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao B.S. Civil Engineering, 2001 Wentworth Institute of Technology Submitted to the Center for Real Estate in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2009 ©2009 Alberto P. Cailao All rights reserved. The author hereby grants MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author________________________________________________________________________ Center for Real Estate July 24, 2009 Certified by_______________________________________________________________________________ David Geltner Professor of Real Estate Finance, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________________________ Brian A. Ciochetti Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao Submitted to the Center for Real Estate on July 24, 2009 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development Abstract This thesis will apply the past research and methodologies of Real Options to Tower 2 and Tower 3 of the World Trade Center redevelopment project in New York, NY. The qualitative component of the thesis investigates the history behind the stalled development of Towers 2 and 3 and examines a potential contingency that could have mitigated the market risk. The quantitative component builds upon that story and creates a hypothetical Real Options case as a framework for applying and valuing building use flexibility in a large-scale, politically charged, real estate development project. -

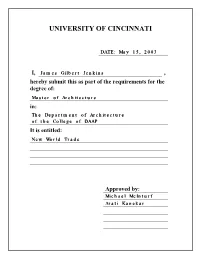

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 15, 2003 I, James Gilbert Jenkins , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: The Department of Architecture of the College of DAAP It is entitled: New World Trade Approved by: Michael McInturf Arati Kanekar NEW WORLD TRADE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the Department of Architecture Of the College of Design, Art, Architecture, and Planing 2003 by James G. Jenkins B.S., University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee Chair : Michael Mcinturf Abstract In these Modern Times, “facts” and “proofs” seem necessary for achieving any credibility in a field where there is a client. To arrive at a “truth,” many architects quickly turn to a dictionary for the final “truth” of a word, such as “privacy” or to a road map to find the “truth” in site conditions, or to a census count for the “truth” of people migration. It is, of coarse, part of the Modern Crisis that many feel the need to go with the way of technology, for fear that Architecture might otherwise fall by the wayside because of its perceived irrelevancy or frivolousness. Following this action, with time, could very well reduce Architecture to a form of methodology and inevitably end with the replacement or removal of the profession from its importance- as creators of a “Truth.” The following thesis is a serious reclamation. The body of work moves to take back for Architecture its power, and specifically it holds up and praises the most important thing we have, but in modern times have been giving away: Life. -

Chapter 5. Historic Resources 5.1 Introduction

CHAPTER 5. HISTORIC RESOURCES 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 CONTEXT Lower Manhattan is home to many of New York City’s most important historic resources and some of its finest architecture. It is the oldest and one of the most culturally rich sections of the city. Thus numerous buildings, street fixtures and other structures have been identified as historically significant. Officially recognized resources include National Historic Landmarks, other individual properties and historic districts listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, properties eligible for such listing, New York City Landmarks and Historic Districts, and properties pending such designation. National Historic Landmarks (NHL) are nationally significant historic places designated by the Secretary of the Interior because they possess exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. All NHLs are included on the National Register, which is the nation’s official list of historic properties worthy of preservation. Historic resources include both standing structures and archaeological resources. Historically, Lower Manhattan’s skyline was developed with the most technologically advanced buildings of the time. As skyscraper technology allowed taller buildings to be built, many pioneering buildings were erected in Lower Manhattan, several of which were intended to be— and were—the tallest building in the world, such as the Woolworth Building. These modern skyscrapers were often constructed alongside older low buildings. By the mid 20th-century, the Lower Manhattan skyline was a mix of historic and modern, low and hi-rise structures, demonstrating the evolution of building technology, as well as New York City’s changing and growing streetscapes. -

AMERICAN ARCHITECTS DIRECTORY KABATNIK B

AMERICAN ARCHITECTS DIRECTORY KABATNIK b. Brooklyn, N.Y, Nov. 29, 37. Educ: B.A, Wesleyan Univ, 59; B.Arch, Mass. JUSTER/BROSMITH/LEVINE. (Sue. to: Howard H. Juster & Partners), Inst. Technol, 61; M.Arch. & M.C.P, Univ. Pa, 64; Rotch Prize, Mass. Inst t 45 E. 51st St, New York, N.Y. 10022. Prins: Howard H. Juster, Bert Technol, 61; Tau Beta Pi, 61; Ecole Americaine des Beaux Arts scholar, 61. Brosmith, Robert H. Levlne, Norton Juster. Pres. Firm: Partner, Ueland & Junker, org. 67, joined firm, 67. Reg: N.J, Pa; NCARB Cert. Prin. Wks: Montgomery Co. Urban Design Study, 68; JUSTESEN, KENNETH ELWOOD. AIA 68. New Jersey Society of Architects Urban Dwelling Syst, Gen. Elec. Co.(study only), Phila, 69; Flaxenburg Arthur Rigolo, Rt. 46 at Grove St, Clifton, N.J. 07013. House, Pine Swamp, Pa, 70; Plan for South Ardmore Commun, 70; Infill Home Add: 19 Winifred Dr, Totowa Boro, N.J. 07512. Housing Syst, Phila, 70. Hon. Awards: Phila. Chap, AIA honor award, 69 & b. Newark, N.J, Mar. 7, 21. Educ: Inst. Design & Construct, Brooklyn, N.Y, Progressive Mech. design award, 70, both for Montgomery Co. Urban De 55-61. Pres. Firm: Proj. mgr, Arthur Rigolo, Clifton, N.J, joined firm, 66. sign Study. Pub. Serv: Mem. housing cmt, Phila. Citizens Coun. City Plan Reg: N.J. Govt. Serv: U.S.A. Inf, 1st Lt, 40-44. ning, 67-69, mem. sch. cmt, 69. JUSTICE, C. C* AIA 44. Virginia Chapter JUNKER, D. J.* AIA 67. Cincinnati Chapter 530 E. Main St. 600, Richmond, Va. -

Architects We Knew Discussion Series on Detroit Architecture at Historical Center WWW ORG

Michigan Bridging Communities And Ideas Humanities A Publication of the Michigan Humanities Council - September 2004 ...Reflecting And Celebrating 30 Years 30th Anniversary In 2004, the forward to the next 30 years of serving just Celebration UMANITIES H Michigan such a vision of civil life. THE FOR Humanities Council is The 30th Anniversary Celebration at The NDOWMENT E pleased to share Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn provides ATIONAL N with you 30 the opportunity to reflect on the past 30 years of public years and look forward to the future. The humanities Council thanks Governor Jennifer programming in Granholm for serving as the event’s Michigan. Honorary Chair and Bruce Cole, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Throughout its Humanities (NEH), for his willingness to life, the share in our celebration and present the Michigan Council’s new We the People grant award NEH Chairman Bruce Cole will provide Humanities winners. Thanks also to jazz musician remarks and will also announce Michigan Humanities Council’s We the People grant Council has Marcus Belgrave and to WDIV-TV morning Master Sponsors award winners understood that show host Guy Gordon. The Michigan the humanities teach us what it means to Humanities Council also appreciates noted Marc Barron be human. They illuminate the lessons of sculptor Stephen Kosinski of Ann Arbor for Marcus Belgrave the past, the ideas that motivate us, the creating the awards for the awards The Dick & Betsy DeVos principles that guide us, and the questions ceremony. Foundation that perplex us. For 30 years, the Council Landon Development Group, LLC has served a central idea: that democracy Thank You Sponsors Jeff & Kathy Padden/Public Policy depends upon educated and thoughtful Associates citizens who fully participate in civic life.