UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan's Historic Preservation Plan

Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Governor Rick Snyder Kevin Elsenheimer, Executive Director, Michigan State Housing Development Authority Brian D. Conway, State Historic Preservation Officer Written by Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner, Michigan State Historic Preservation Office with assistance from Alan Levy and Kristine Kidorf Goaltrac, Inc. For more information on Michigan’s historic preservation programs visit michigan.gov/SHPo. The National Park Service (NPS), U. S. Department of the Interior, requires each State Historic Preservation Office to develop and publish a statewide historic preservation plan every five years. (Historic Preservation Fund Grants Manual, Chapter 6, Section G) As required by NPS, Michigan’s Five-Year Historic Preservation Plan was developed with public input. The contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. The activity that is the subject of this project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. However, the contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilita- tion Act of 1973 and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Challenges and Achievements

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture NISEI ARCHITECTS: CHALLENGES AND ACHIEVEMENTS A Thesis in Architecture by Katrin Freude © 2017 Katrin Freude Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture May 2017 The Thesis of Katrin Freude was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alexandra Staub Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Advisor Denise Costanzo Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Co-Advisor Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Architecture Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History Ute Poerschke Associate Professor of Architecture Director of Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Japanese-Americans and their culture have been perceived very ambivalently in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century; while they mostly faced discrimination for their ethnicity by the white majority in the United States, there has also been a consistent group of admirers of the Japanese art and architecture. Nisei (Japanese-Americans of the second generation) architects inherited the racial stigma of the Japanese minority but increasingly benefited from the new aesthetic light that was cast, in both pre- and post-war years, on Japanese art and architecture. This thesis aims to clarify how Nisei architects dealt with this ambivalence and how it was mirrored in their professional lives and their built designs. How did architects, operating in the United States, perceive Japanese architecture? How did these perceptions affect their designs? I aim to clarify these influences through case studies that will include such general issues as (1) Japanese-Americans’ general cultural evolution, (2) architects operating in the United States and their relation to Japanese architecture, and (3) biographies of three Nisei architects: George Nakashima, Minoru Yamasaki, and George Matsumoto. -

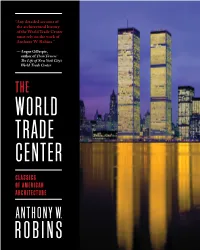

To Read Sample Pages

“ Any detailed account of the architectural history of the World Trade Center must rely on the work of Anthony W. Robins.” — Angus Gillespie, author of Twin Towers: Th e Life of New York City’s World Trade Center THE WORLD TRADE CENTER CLASSICS OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE ANTHONY W. ROBINS Originally published in 1987 while the Twin Towers still stood — brash and controversial, a new symbol of the city and the country — this book off ered the fi rst serious con- sideration of the planning and design of the World Trade Center. It benefi ted from interviews with fi gures still on the scene, and archival documents still available for study. Many of those interviewed, and many of the documents, are gone. But even if they remained available today, it would be impossible now to write this book from the same perspective. Too much has happened here. In this, the tenth anniversary year of the disaster, a new World Trade Center is rising on the site. We can fi nally begin to imagine life returning, with thousands of people streaming into the new build- ings to work or conduct business, and thousands more, from all over the world, coming to visit the new memorial. It is only natural, then, that we will fi nd ourselves thinking about what life was like in the original Center. Th is new edition of the book — expanded to include copies of some of the documents upon which the text was based — is off ered as a memory of the World Trade Center as it once was. -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. Cover Photography © Mike Billick Issue 44 The Rustic Majesty of the Wilderness Lodge 42 Contents Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News ...........................................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................16 Darling Daughters: Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett ......................................................................18 Diane & Sharon Disney 52 Shutters & Lenses by Tim Devine .........................................................................20 Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................24 Disney Cuisine by Allison Jones ......................................................................26 Disney Touring Tips by Carrie Hurst .......................................................................28 -

Modelsurvivor

CG Spring 04Fn5.cc 2/24/04 11:59 AM Page 10 GRANT SPOTLIGHT MODEL SURVIVOR Restoring an Architect’s Miniature Masterwork Though a prominent part of New York’s skyline—and a symbol of the city itself—the THE RESTORATION Twin Towers were originally viewed with skepticism. To win over the skeptics, architect WAS LED BY A MODEL Minoru Yamasaki expressed his vision with an elaborately detailed model, today the only MAKER WITH surviving three-dimensional representation of the World Trade Center. CONSERVATION The events of September 11, 2001, have imbued the model with significance that its creators could EXPERTISE AND THE never have imagined. Now part of the American Architectural Foundation’s prints and drawings col- FORMER CHIEF OF lection, the model has undergone a complete restoration thanks to the congressionally funded Save YAMASAKI’S MODEL America’s Treasures grant program of the National Park Service. SHOP, WHOSE The model was donated to the foundation’s collection in 1992, but little is known about its travels KNOWLEDGE OF THE over the past 30 years. What was immediately evident was the urgent need to arrest its worsening con- FIRM’S TECHNIQUES dition. The model is seven feet tall and eight by ten feet at its base; its size, weight, and difficult assem- bly (three hours minimum) did not work in its favor. FOR MODEL-BUILDING “An intriguing and complex period piece in very fragile condition,” is how the foundation described AT THE TIME WAS it. Delicate by nature, architectural models are easily damaged. Often kept in less-than-ideal condi- INVALUABLE. -

Blue Cross Likes That Mutual Feeling

20150309-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 3/6/2015 5:50 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 31, No. 10 MARCH 9 – 15, 2015 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2015 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved One year into life LOOKING BACK Minoru Page 3 as a nonprofit Yamasaki was hired mutual, to design Brookfield Office Honigman hires Carl Levin expect more to design Brookfield Office change, Blue Cross Park, a high-end complex to advise on government CEO Loepp in Farmington Hills says. At Roush Industries, theme park biz ups, downs are OK likes that 2 Cobo events allow young innovators to see the D CRAIN’S MICHIGAN BUSINESS COURTESY OF BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD OF MICHIGAN mutual feeling Hotel demand raises supply – that’s good, maybe, Page 15 has garnered more than Insurer uses its 100,000 subscribers and ar- guably forced competitors to lower prices. new nonprofit “We have the opportu- nity to grow nationally as we are now a nonprofit mutual status to mutual,” Loepp said. “We are in a spot where we are COURTESY OF ETKIN LLC looking” at possible in- Brookfield Office Park (above) was one of the final chart growth works of Minoru Yamasaki but one of many local Loepp vestments in health com- buildings he designed, including Temple Beth El. BY JAY GREENE panies or joint ventures CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS with other Blues plans, he said. For example, Loepp said, the Accident Fund Dan Loepp says there have been many Insurance Co. of America, a Blue Cross for- changes at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan profit subsidiary that sells workers’ com- The new Crainsdetroit.com: during its first full year as a nonprofit mutu- pensation insurance, “now has the ability to Yamasaki’s al health insurance company. -

Present and Future Market Value of Fiesta Texas

University of Central Florida STARS Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers Digital Collections 9-1-1994 Present and Future Market Value of Fiesta Texas Harrison Price Company Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Harrison Price Company, "Present and Future Market Value of Fiesta Texas" (1994). Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 163. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/163 PRESENT AND FUTURE MARKET VALUE OF FIESTA TEXAS San Antonio, Texas Prepared for La Cantera Development Company September 1994 Prepared by HARRISON PRICE COMPANY 222 West 6th Street, Suite 1000, San Pedro, CA 90731 PHONE (310) 521-1300 FAX (310) 521-1305 PRESENT AND FUTURE MARKET VALUE OF FIESTA TEXAS San Antonio, Texas Prepared for La Cantera Development Company September 1994 Prepared by HARRISON PRICE COMPANY 222 West 6th Street, Suite 1000, San Pedro, CA 90731 PHONE (310) 521-1300 FAX (310) 521-1305 HARRISON PRICE COMPANY September21, 1994 Mr. Sam Mitts, CPA Assistant Vice President Finance and Operations La Cantara Development Company 9800 Fredericksburg Road San Antonio, Texas 78288-0385 Dear Mr. Mitts: Enclosed is our appraisal of the present market value. of Fiesta Texas defined as the value a willing buyer with a strong interest in the San Antonio market would likely pay for the park assets including its land. -

CUSS Newsletter

American Sociological Association Volume 28 Number 3 Community & Urban Sociology Section Summer 2016 CUSS Newsletter INSIDE THIS ISSUE: CONFERENCE FEATURE: URBAN CASCADIA Ryan Centner ure 1), including innova- London School tions and inequalities. of Economics Cascadia, to begin, is a somewhat contested term For those of you at- (Helm 1993; Smith 2008; tending the Seattle annu- Abbott 2009). As a re- -Editor’s Note 3 al meetings: Welcome to gional moniker, clearly it -News & Notes 4 the northwestern edge of references the Cascade -Calls for Submissions the Americas – Range of mountains that “Cascadia” – a region I run from northern Califor- The Seattle skyline is in the mid- -CUSS Election Results 5 am proud to call home, nia up to southern British dle of the Cascadia Corridor along -New Dissertations -New Books 6 even though I currently Columbia. Its vernacular I-5. live some 5,000 miles origins derive from popu- Conference Features: away in an increasingly lar depictions of the Pa- -Climate Change, Trau- 15 wash of winds and wa- ma, and Coastal Cities provincial archipelago cific Northwest as a kind ters. As a distinct region, -Glimpse of Seattle 19 known as the British of “ecotopia” (Callenbach Cascadia arises from Isles. If this is your first 1975; Garreau 1981), both a natural integrity encounter with the Pacific reflecting both a unique (e.g., landforms and -2016 ASA CUSS Panels 24 Northwest, you may be landscape and unusual & Roundtables earth-plates, weather pat- -2016 CUSS Awards 25 scratching your head. society-environment rela- terns and ocean currents, -2016 ASA CUSS 28 What is Cascadia? And tionship. -

University of Central Florida Libraries, Annual Report 2011-2012

University of Central Florida STARS Libraries' Documents 2012 University of Central Florida Libraries, Annual Report 2011-2012 UCF Libraries University of Central Florida Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/lib-docs University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Report is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Libraries' Documents by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Libraries, UCF, "University of Central Florida Libraries, Annual Report 2011-2012" (2012). Libraries' Documents. 127. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/lib-docs/127 Libraries Annual Report 2011-2012 Table of Contents Director’s Overview ............................................................... 1 Administrative Services Administrative Services ............................................. 6 Curriculum Materials Center ...................................... 9 Regional Campus Libraries ....................................... 12 Universal Orlando Foundation Library ..................... 14 Collections & Technical Services ....................................................... 19 Acquisitions & Collections Services ......................... 21 Cataloging Services .................................................. 30 Public Services, Associate Director’s Summary .................. 36 Circulation Services ................................................. 37 Information Literacy & Outreach ............................ -

You're on Stage at Disney World: an Analysis of Main

YOU’RE ON STAGE AT DISNEY WORLD: AN ANALYSIS OF MAIN STREET, USA IN THE MAGIC KINGDOM by MARISA N. SCALERA (Under the Direction of Henry Methvin) ABSTRACT This thesis explores the image and physical characteristics of Main Street, USA in the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, Florida. The first chapter explores the questions: What thematic roles does Main Street, USA play within the Magic Kingdom, within our collective national consciousness, and across the world? The second chapter asks: How does the visitor relate to Main Street, USA? How do these interactions change throughout the course of a day? The third chapter asks: What are the defining physical characteristics of Main Street, USA? How do these characteristics influence the experience of the visitor? All three chapters use the metaphor of a show that takes place daily on the Main Street, USA stage and in which visitors are both audience and actors. Through this examination both reader and author will gain a better understanding of the composition of Main Street, USA and insight into this undeniable design force. INDEX WORDS: Magic Kingdom; Disney World; Theme Parks – Florida; American Architecture; 20th Century Architecture YOU’RE ON STAGE AT DISNEY WORLD: AN ANALYSIS OF MAIN STREET, USA IN THE MAGIC KINGDOM by MARISA N. SCALERA B.A., Agnes Scott College, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 © 2002 Marisa N. Scalera All Rights Reserved YOU’RE ON STAGE AT DISNEY WORLD: AN ANALYSIS OF MAIN STREET, USA IN THE MAGIC KINGDOM by MARISA N. -

The Brave $Tatement Issue 5 Autumn 2000

The Brave $tatement Issue 5 Autumn 2000 Theme Parks Capex Management - Searching for Predictability Theme Parks Capex Page 1 The Forgotten Guest Page 4 The dream had some basis in truth. In the ‘50s and ‘60s Walt was ploughing almost all the profits from Disneyland back into the park. His brother Roy was worried. Roy sensed there ought to be some kind of rational limit on reinvestment and he hoped he was approaching it because Walt was spending all the profits - literally. Roy had actually asked me for a study defining rational reinvestment levels. At the time, I couldn’t think of how to do that. Our industry was too new. There just wasn’t enough data In the Winter edition, with our USA associates, available. Harrison Price Company, PKFCA examined examples of why the attraction business deserves Then it hit me! In my dream the ghost of Roy had public support. come back to get his report now, because 35 years later the data was available. After performing 3,000+ This issue carries the theme (no pun) forward. Based studies over the last 48 years, I had what I needed. on our work together on several theme park projects, we have asked Harrison (Buzz) Price) to prepare this I mumbled “Thank you, Roy”, and, wide awake, I article. Buzz carried out the first feasibility study for dove into my half-century accumulation of paper. Walt Disney in the ‘50s - another one the bankers Everyone agrees you need to reinvest that if you said would never work. Buzz deals with the critical issue of capital reinvestment and its impact on don’t freshen your product the public will stop theme park attendance.