Challenges and Achievements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan's Historic Preservation Plan

Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Governor Rick Snyder Kevin Elsenheimer, Executive Director, Michigan State Housing Development Authority Brian D. Conway, State Historic Preservation Officer Written by Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner, Michigan State Historic Preservation Office with assistance from Alan Levy and Kristine Kidorf Goaltrac, Inc. For more information on Michigan’s historic preservation programs visit michigan.gov/SHPo. The National Park Service (NPS), U. S. Department of the Interior, requires each State Historic Preservation Office to develop and publish a statewide historic preservation plan every five years. (Historic Preservation Fund Grants Manual, Chapter 6, Section G) As required by NPS, Michigan’s Five-Year Historic Preservation Plan was developed with public input. The contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. The activity that is the subject of this project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. However, the contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilita- tion Act of 1973 and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

To Read Sample Pages

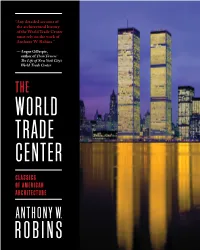

“ Any detailed account of the architectural history of the World Trade Center must rely on the work of Anthony W. Robins.” — Angus Gillespie, author of Twin Towers: Th e Life of New York City’s World Trade Center THE WORLD TRADE CENTER CLASSICS OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE ANTHONY W. ROBINS Originally published in 1987 while the Twin Towers still stood — brash and controversial, a new symbol of the city and the country — this book off ered the fi rst serious con- sideration of the planning and design of the World Trade Center. It benefi ted from interviews with fi gures still on the scene, and archival documents still available for study. Many of those interviewed, and many of the documents, are gone. But even if they remained available today, it would be impossible now to write this book from the same perspective. Too much has happened here. In this, the tenth anniversary year of the disaster, a new World Trade Center is rising on the site. We can fi nally begin to imagine life returning, with thousands of people streaming into the new build- ings to work or conduct business, and thousands more, from all over the world, coming to visit the new memorial. It is only natural, then, that we will fi nd ourselves thinking about what life was like in the original Center. Th is new edition of the book — expanded to include copies of some of the documents upon which the text was based — is off ered as a memory of the World Trade Center as it once was. -

GYO OBATA and the WORK of HOK: Renowned Designer to Address Design Conference by Steven C

GYO OBATA AND THE WORK OF HOK: Renowned Designer to Address Design Conference by Steven C. Yesner, AlA HELLMUTH, OBATA& KASSABAUM, familiarly known as HOK, is one of the five largest architectural design firms in the U.S., headquarteredin St. Louis, with offices in Dallas, Houston, Kansas City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Washing ton, D.C., Tampa, Denver, London and Hong Kong. It is recog nized internationallyfor the scope ofi ts projects and diversity of its practice, which includes architecture, engineering, interior design, landscape architecture, graphic design, facility pro gramming and computer-aided design . Gyo Obata, FAIA, is chairman, presidentand chiefexecutive officer of HOK, Inc. Beyond his administrative duties, he establishes the fundamental design direction for the finn, work ingclosely with the designers ofeach office to develop andrefine projects to their final form. Obata will give the keynote address at the 1988 Santa Fe Design Conference. While he is in New Mexico, he will undoubt edly take the opportunity to visit HOK's current project in Albuquerque, the BetaWest mixed-use development next to Civic Plaza. Growth of a Corporate Giant Obata comes from a long line of Japanese classical artists. His father, who was a professor of art at the University of Californiain Berkeley, introduced the traditional sumi-estyle of painting to the West Coast. His mother did the same thing for ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. Obata studied at Berkeley, Washington University in St . Louis and Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, completing degrees in architecture and urban design. After serving in the U.S. -

Modelsurvivor

CG Spring 04Fn5.cc 2/24/04 11:59 AM Page 10 GRANT SPOTLIGHT MODEL SURVIVOR Restoring an Architect’s Miniature Masterwork Though a prominent part of New York’s skyline—and a symbol of the city itself—the THE RESTORATION Twin Towers were originally viewed with skepticism. To win over the skeptics, architect WAS LED BY A MODEL Minoru Yamasaki expressed his vision with an elaborately detailed model, today the only MAKER WITH surviving three-dimensional representation of the World Trade Center. CONSERVATION The events of September 11, 2001, have imbued the model with significance that its creators could EXPERTISE AND THE never have imagined. Now part of the American Architectural Foundation’s prints and drawings col- FORMER CHIEF OF lection, the model has undergone a complete restoration thanks to the congressionally funded Save YAMASAKI’S MODEL America’s Treasures grant program of the National Park Service. SHOP, WHOSE The model was donated to the foundation’s collection in 1992, but little is known about its travels KNOWLEDGE OF THE over the past 30 years. What was immediately evident was the urgent need to arrest its worsening con- FIRM’S TECHNIQUES dition. The model is seven feet tall and eight by ten feet at its base; its size, weight, and difficult assem- bly (three hours minimum) did not work in its favor. FOR MODEL-BUILDING “An intriguing and complex period piece in very fragile condition,” is how the foundation described AT THE TIME WAS it. Delicate by nature, architectural models are easily damaged. Often kept in less-than-ideal condi- INVALUABLE. -

Blue Cross Likes That Mutual Feeling

20150309-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 3/6/2015 5:50 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 31, No. 10 MARCH 9 – 15, 2015 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2015 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved One year into life LOOKING BACK Minoru Page 3 as a nonprofit Yamasaki was hired mutual, to design Brookfield Office Honigman hires Carl Levin expect more to design Brookfield Office change, Blue Cross Park, a high-end complex to advise on government CEO Loepp in Farmington Hills says. At Roush Industries, theme park biz ups, downs are OK likes that 2 Cobo events allow young innovators to see the D CRAIN’S MICHIGAN BUSINESS COURTESY OF BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD OF MICHIGAN mutual feeling Hotel demand raises supply – that’s good, maybe, Page 15 has garnered more than Insurer uses its 100,000 subscribers and ar- guably forced competitors to lower prices. new nonprofit “We have the opportu- nity to grow nationally as we are now a nonprofit mutual status to mutual,” Loepp said. “We are in a spot where we are COURTESY OF ETKIN LLC looking” at possible in- Brookfield Office Park (above) was one of the final chart growth works of Minoru Yamasaki but one of many local Loepp vestments in health com- buildings he designed, including Temple Beth El. BY JAY GREENE panies or joint ventures CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS with other Blues plans, he said. For example, Loepp said, the Accident Fund Dan Loepp says there have been many Insurance Co. of America, a Blue Cross for- changes at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan profit subsidiary that sells workers’ com- The new Crainsdetroit.com: during its first full year as a nonprofit mutu- pensation insurance, “now has the ability to Yamasaki’s al health insurance company. -

Nasa Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Oral History Transcript

NASA JOHNSON SPACE CENTER ORAL HISTORY PROJECT ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT FAROUK EL-BAZ INTERVIEWED BY REBECCA WRIGHT BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS – NOVEMBER 2, 2009 WRIGHT: Today is November 2, 2009. This oral history interview is being conducted with Dr. Farouk El-Baz in Boston, Massachusetts, for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Interviewer is Rebecca Wright, assisted by Jennifer Ross-Nazzal. We certainly would like to start by telling you thank you. We know you‘re a very busy person with a very busy schedule, so thank you for finding time for us today. EL-BAZ: You‘re welcome to come here, because this is part of the history of the United States. It‘s important that we all chip in. WRIGHT: We‘re glad to hear that. We know your work with NASA began as early as 1967 when you became employed by Bellcomm [Incorporated]. Could you share with us how you learned about that opportunity and how you made that transition into becoming an employee there? EL-BAZ: Just the backdrop, I finished my PhD here in the US. First job offer was from Germany. It was in June 1964; I was teaching there [at the University of Heidelberg] until December 1965. I went to Egypt then, tried to get a job in geology. I was unable for a whole year, so I came back to the US as an immigrant in the end of 1966. For the first three months of 1967, I began to search for a job. When I arrived in the winter, most of the people that I knew 2 November 2009 1 Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Farouk El-Baz were at universities, and most universities had hired the people that would teach during the year. -

Symbolism and the City: from Towers of Power to 'Ground Zero'

Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays (Vol: 15) Symbolism and the city: From towers of power to ‘Ground Zero’ Robert Patrick University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada Amy MacDonald University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Canada Abstract This paper explores the symbolism of New York City’s World Trade Center (WTC) before and after the devastating attack of September 11, 2001. The many metaphors captured in the built space of the WTC site are interrogated from ‘Ground Zero’ to the symbolic significance of the new ‘Freedom Tower’ now nearing completion (2014). In fulfilling the intended symbolism of American economic power, the WTC towers became pop-culture symbols of New York City, and the Unit- ed States. The WTC towers stood as twin icons of western economic dominance along with ‘Wall Street’ and ‘Dow Jones’ reflecting the American ethos of freedom and opportunity. However, the WTC also imbued negative, albeit unintended, symbolism such as the coldness of modernist architecture, social class disparities across urban America, and global domina- tion. Plans for redeveloping the WTC site predominantly highlight the intended positive symbolic connotations of the for- mer Twin Towers, including freedom and opportunity. This article points to the symbolic significance of urban built form and the potential negative consequences that are associated with iconic structures, including the new Freedom Tower. Keywords: symbolism, iconic architecture, New York City, World Trade Center Introduction tions leading to positive and negative actions of individuals and On September 11, 2001 a terrorist attack of horrific propor- groups. Indeed, there is a long fascination among geographers tions destroyed the New York World Trade Center and surround- and planners to the symbolic functions of ‘architectural gigan- ing structures. -

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2019-4766-HCM ENV-2019-4767-CE HEARING DATE: September 5, 2019 Location: 2421-2425 North Silver Ridge Avenue TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 13 – O’Farrell PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Silver Lake – Echo Park – 200 N. Spring Street Elysian Valley Los Angeles, CA 90012 Area Planning Commission: East Los Angeles Neighborhood Council: Silver Lake Legal Description: Tract 6599, Lots 15-16 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HAWK HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property an Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Bryan Libit APPLICANT: 2421 Silver Ridge Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90039 PREPARER: Jenna Snow PO Box 5201 Sherman Oaks, CA 91413 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as an Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Melissa Jones, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachment: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2019-4766-HCM 2421-2425 Silver Ridge Avenue Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The Hawk House is a two-story single-family residence and detached garage located on Silver Ridge Avenue in Silver Lake. Constructed in 1939, it was designed by architect Harwell Hamilton Harris (1903-1990) in the Early Modern architectural style for Edwin “Stan” Stanton and Ethyle Hawk. -

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71St Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71st Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Saint Paul, Minnesota, 18–22 April 2018 All Ado About Bomarzo Architecture of Diplomacy and Defense Anatole Tchikine, Dumbarton Oaks, USA, Session Chair Cynthia G. Falk, State University of New York at Oneonta, USA, and Lisa P. Davidson, HABS—National Park Service, USA, “Landscape Architecture without Architects: Bomarzo and the Vernac- Session Co-Chairs ular,” Katherine Coty, University of Washington, USA “Cannibals, Grottoes and Vicino Orsini’s Sacro Bosco,” Luke Mor- “Building and Abandoning U.S. Naval Station Tutuila,” Kelema gan, Monash University, Australia Moses, Occidental College, USA “Botanicals and Symbolism in the Landscape of Bomarzo,” John “Border Stakes: Architecture as Diplomatic Tool in Contested Inter- Garton, Clark University, USA war Italo-Yugoslav Territories,” Matthew Worsnick, Institute of “‘Impressions so alien’: The Postwar Afterlife of the Sacro Fine Arts (NYU), USA Bosco,” Thalia Allington-Wood, University College “Architectural Mechanism of the Frontier Villages at the Korean London, UK Border,” Alex Young Il Seo, University of Cambridge, UK “Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden and the Legacies of Bomarzo,” “The Architecture of Peace in the Middle East,” Neta Feniger, John Beardsley, Dumbarton Oaks, USA Te c h n i o n —Israel Institute of Technology The Architecture of Commercial Networks, 1500–1900 Life to Architecture: Uncovering Women’s Narratives Katie Jakobiec, University of Oxford, -

Los Angeles City Planning Department

RALPH JOHNSON HOUSE 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane CHC-2016-508-HCM ENV-2016-509-CE Agenda packet includes 1. Final Staff Recommendation Report 2. Categorical Exemption 3. Under Consideration Staff Recommendation Report 4. Nomination Please click on each document to be directly taken to the corresponding page of the PDF. Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2016-508-HCM ENV-2016-509-CE Location: 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane HEARING DATE: April 21, 2016 Council District: 5 TIME: 9:00 AM Community Plan Area: Bel-Air Beverly Crest PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Area Planning Commission: West 200 N. Spring Street Neighborhood Council: Bel-Air Beverly Crest Los Angeles, CA 90012 Legal Description: TR 1033, Block 31, Lot 15, 16, EXPIRATION DATE: May 17, 2016 53, 54, and 55 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the RALPH JOHNSON HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Viet-Nu Nguyen APPLICANT: 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane Los Angeles, CA 90077 PREPARER: Anna Marie Brooks 1109 4th Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90019 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the subject property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7. 2. Adopt the staff report and findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2016-508-HCM 10261 Chrysanthemum Lane Page 2 of 4 FINDINGS The Ralph Johnson House "embodies the distinguishing characteristics of an architectural-type specimen, inherently valuable for study of a period, style or method of construction” as an example of the Mid-Century Modern style with heavy Craftsman influences. -

EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Eames House Other Name/Site Number: Case Study House #8 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 203 N Chautauqua Boulevard Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Pacific Palisades Vicinity: N/A State: California County: Los Angeles Code: 037 Zip Code: 90272 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): x Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing: Noncontributing: 2 buildings sites structures objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: None Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria.