Architecture and Trauma in New York and Hiroshima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan's Historic Preservation Plan

Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Michigan’s state historic Preservation Plan 2014–2019 Governor Rick Snyder Kevin Elsenheimer, Executive Director, Michigan State Housing Development Authority Brian D. Conway, State Historic Preservation Officer Written by Amy L. Arnold, Preservation Planner, Michigan State Historic Preservation Office with assistance from Alan Levy and Kristine Kidorf Goaltrac, Inc. For more information on Michigan’s historic preservation programs visit michigan.gov/SHPo. The National Park Service (NPS), U. S. Department of the Interior, requires each State Historic Preservation Office to develop and publish a statewide historic preservation plan every five years. (Historic Preservation Fund Grants Manual, Chapter 6, Section G) As required by NPS, Michigan’s Five-Year Historic Preservation Plan was developed with public input. The contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. The activity that is the subject of this project has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. However, the contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Michigan State Housing Development Authority. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilita- tion Act of 1973 and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. -

Challenges and Achievements

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture NISEI ARCHITECTS: CHALLENGES AND ACHIEVEMENTS A Thesis in Architecture by Katrin Freude © 2017 Katrin Freude Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture May 2017 The Thesis of Katrin Freude was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alexandra Staub Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Advisor Denise Costanzo Associate Professor of Architecture Thesis Co-Advisor Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Architecture Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History Ute Poerschke Associate Professor of Architecture Director of Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Japanese-Americans and their culture have been perceived very ambivalently in the United States in the middle of the twentieth century; while they mostly faced discrimination for their ethnicity by the white majority in the United States, there has also been a consistent group of admirers of the Japanese art and architecture. Nisei (Japanese-Americans of the second generation) architects inherited the racial stigma of the Japanese minority but increasingly benefited from the new aesthetic light that was cast, in both pre- and post-war years, on Japanese art and architecture. This thesis aims to clarify how Nisei architects dealt with this ambivalence and how it was mirrored in their professional lives and their built designs. How did architects, operating in the United States, perceive Japanese architecture? How did these perceptions affect their designs? I aim to clarify these influences through case studies that will include such general issues as (1) Japanese-Americans’ general cultural evolution, (2) architects operating in the United States and their relation to Japanese architecture, and (3) biographies of three Nisei architects: George Nakashima, Minoru Yamasaki, and George Matsumoto. -

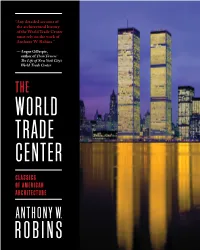

To Read Sample Pages

“ Any detailed account of the architectural history of the World Trade Center must rely on the work of Anthony W. Robins.” — Angus Gillespie, author of Twin Towers: Th e Life of New York City’s World Trade Center THE WORLD TRADE CENTER CLASSICS OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE ANTHONY W. ROBINS Originally published in 1987 while the Twin Towers still stood — brash and controversial, a new symbol of the city and the country — this book off ered the fi rst serious con- sideration of the planning and design of the World Trade Center. It benefi ted from interviews with fi gures still on the scene, and archival documents still available for study. Many of those interviewed, and many of the documents, are gone. But even if they remained available today, it would be impossible now to write this book from the same perspective. Too much has happened here. In this, the tenth anniversary year of the disaster, a new World Trade Center is rising on the site. We can fi nally begin to imagine life returning, with thousands of people streaming into the new build- ings to work or conduct business, and thousands more, from all over the world, coming to visit the new memorial. It is only natural, then, that we will fi nd ourselves thinking about what life was like in the original Center. Th is new edition of the book — expanded to include copies of some of the documents upon which the text was based — is off ered as a memory of the World Trade Center as it once was. -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

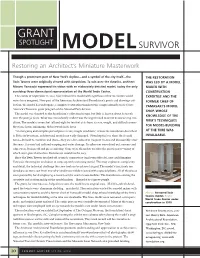

Modelsurvivor

CG Spring 04Fn5.cc 2/24/04 11:59 AM Page 10 GRANT SPOTLIGHT MODEL SURVIVOR Restoring an Architect’s Miniature Masterwork Though a prominent part of New York’s skyline—and a symbol of the city itself—the THE RESTORATION Twin Towers were originally viewed with skepticism. To win over the skeptics, architect WAS LED BY A MODEL Minoru Yamasaki expressed his vision with an elaborately detailed model, today the only MAKER WITH surviving three-dimensional representation of the World Trade Center. CONSERVATION The events of September 11, 2001, have imbued the model with significance that its creators could EXPERTISE AND THE never have imagined. Now part of the American Architectural Foundation’s prints and drawings col- FORMER CHIEF OF lection, the model has undergone a complete restoration thanks to the congressionally funded Save YAMASAKI’S MODEL America’s Treasures grant program of the National Park Service. SHOP, WHOSE The model was donated to the foundation’s collection in 1992, but little is known about its travels KNOWLEDGE OF THE over the past 30 years. What was immediately evident was the urgent need to arrest its worsening con- FIRM’S TECHNIQUES dition. The model is seven feet tall and eight by ten feet at its base; its size, weight, and difficult assem- bly (three hours minimum) did not work in its favor. FOR MODEL-BUILDING “An intriguing and complex period piece in very fragile condition,” is how the foundation described AT THE TIME WAS it. Delicate by nature, architectural models are easily damaged. Often kept in less-than-ideal condi- INVALUABLE. -

Akaa2007 Final 01-65:Akdn 2007

AKAA2007_FINAL_130-192:AKDN 2007 24/7/07 16:02 Page 181 180 AKAA2007_FINAL_130-192:AKDN 2007 24/7/07 16:02 Page 182 Aga Khan Award for Architecture Aga Khan Award for Architecture Retrospective 1977 – 2007 Over the past 30 years, the Aga Khan Award has recognised outstanding architectural achievements in some 32 countries. It has held seminars, conferences and exhibitions to explore and discuss the crucial issues of the built environment, and published the proceedings to bring these subjects to a wider audience. It has brought together the architectural community and policy-makers to celebrate the prize-winning projects of 10 award cycles in important historical and architectural settings, and has invited the leading thinkers and practitioners of the day to frame the discourse 10 th on architectural excellence within the context of successive master juries and steering committees. Cycle 1st Cycle 6th Cycle Award Award Ceremony Ceremony Pakistan 1980 Indonesia 1995 2nd Cycle 7th Cycle Award Award Ceremony Ceremony Turkey 1983 Spain 1998 3rd Cycle 8th Cycle Award Award Ceremony Ceremony Morocco 1986 Syria 2001 4th Cycle 9th Cycle Award Award Ceremony Ceremony Egypt 1989 India 2004 Building for Change With an introduction by Homi K. Bhabha 5th Cycle Samir Kassir Square Beirut Lebanon 10th Cycle Award Rehabilitation of the City of Shibam Yemen Award Ceremony Central Market Koudougou Burkina Faso Ceremony 182 183 Uzbekistan 1992 University of Technology Petronas Bandar Seri Iskandar Malaysia Malaysia 2007 Restoration of the Amiriya Complex -

Xx January 2017

The Japanese House Architecture and Life after 1945 Barbican Art Gallery, Barbican Centre 23 March – 25 June 2017 Media View, Wednesday 22 March, 10am –1pm #thejapanesehouse The exhibition is co-organised and co-produced by the Japan Foundation Sponsored by Kajima, Japan Centre, Shiseido and Natrium Capital With additional support from Japan Airlines, The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation Media Partner: Elle Decoration The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945 is the first major UK exhibition to focus on Japanese domestic architecture from the end of the Second World War to now, a field which has consistently produced some of the most influential and extraordinary examples of modern and contemporary design. The exhibition features over 40 architects, ranging from renowned 20th century masters and internationally celebrated contemporary architects such as Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito, Kazuyo Sejima (SANAA) and Kenzo Tange; to exciting figures little known outside of Japan including Osamu Ishiyama, Kazunari Sakamoto and Kazuo Shinohara, and young rising stars such as Hideyuki Nakayama and Chie Konno. The Japanese House presents some of the most ground- breaking architectural projects of the last 70 years, many of which have never before been exhibited in the UK. The exhibition also incorporates film and photography in order to cast a new light on the role of the house in Japanese culture. The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945 opens at Barbican Art Gallery on 23 March 2017. Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts said “I couldn’t be more delighted that we are able to now stage this pioneering, timely exhibition that forefronts some of the most astounding work by Japanese architects in the post-war period. -

Blue Cross Likes That Mutual Feeling

20150309-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 3/6/2015 5:50 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 31, No. 10 MARCH 9 – 15, 2015 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2015 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved One year into life LOOKING BACK Minoru Page 3 as a nonprofit Yamasaki was hired mutual, to design Brookfield Office Honigman hires Carl Levin expect more to design Brookfield Office change, Blue Cross Park, a high-end complex to advise on government CEO Loepp in Farmington Hills says. At Roush Industries, theme park biz ups, downs are OK likes that 2 Cobo events allow young innovators to see the D CRAIN’S MICHIGAN BUSINESS COURTESY OF BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD OF MICHIGAN mutual feeling Hotel demand raises supply – that’s good, maybe, Page 15 has garnered more than Insurer uses its 100,000 subscribers and ar- guably forced competitors to lower prices. new nonprofit “We have the opportu- nity to grow nationally as we are now a nonprofit mutual status to mutual,” Loepp said. “We are in a spot where we are COURTESY OF ETKIN LLC looking” at possible in- Brookfield Office Park (above) was one of the final chart growth works of Minoru Yamasaki but one of many local Loepp vestments in health com- buildings he designed, including Temple Beth El. BY JAY GREENE panies or joint ventures CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS with other Blues plans, he said. For example, Loepp said, the Accident Fund Dan Loepp says there have been many Insurance Co. of America, a Blue Cross for- changes at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan profit subsidiary that sells workers’ com- The new Crainsdetroit.com: during its first full year as a nonprofit mutu- pensation insurance, “now has the ability to Yamasaki’s al health insurance company. -

Symbolism and the City: from Towers of Power to 'Ground Zero'

Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays (Vol: 15) Symbolism and the city: From towers of power to ‘Ground Zero’ Robert Patrick University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada Amy MacDonald University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Canada Abstract This paper explores the symbolism of New York City’s World Trade Center (WTC) before and after the devastating attack of September 11, 2001. The many metaphors captured in the built space of the WTC site are interrogated from ‘Ground Zero’ to the symbolic significance of the new ‘Freedom Tower’ now nearing completion (2014). In fulfilling the intended symbolism of American economic power, the WTC towers became pop-culture symbols of New York City, and the Unit- ed States. The WTC towers stood as twin icons of western economic dominance along with ‘Wall Street’ and ‘Dow Jones’ reflecting the American ethos of freedom and opportunity. However, the WTC also imbued negative, albeit unintended, symbolism such as the coldness of modernist architecture, social class disparities across urban America, and global domina- tion. Plans for redeveloping the WTC site predominantly highlight the intended positive symbolic connotations of the for- mer Twin Towers, including freedom and opportunity. This article points to the symbolic significance of urban built form and the potential negative consequences that are associated with iconic structures, including the new Freedom Tower. Keywords: symbolism, iconic architecture, New York City, World Trade Center Introduction tions leading to positive and negative actions of individuals and On September 11, 2001 a terrorist attack of horrific propor- groups. Indeed, there is a long fascination among geographers tions destroyed the New York World Trade Center and surround- and planners to the symbolic functions of ‘architectural gigan- ing structures. -

Kenzo Tange, Tokyo Bay Project (1960)

Kenzo Tange, Tokyo Bay Project (1960). Kenzo Tange, Tokyo Bay Project (1960) Top: Design for Caen-Herouville by Shadrach Woods of Team X, published in Urbanism Is Everybody's Business (Stuttgart: Karl Krämer, 1968) Bottom: A new urban structure imposed upon an older fabric. Based on a drawing by Yona Friedman in L'Architecture Mobile (Tournai, Belgium: Casterman, 1970.) 1 Kenzo Tange, Tokyo Bay Project (1960); transit network and housing quarters The 1933 rendering of Plan Obus for Algiers demonstrates Le Corbusier's superimposition of modern forms: the long arching roadway that includes housing- his viaduct city- connecting central Algiers to its suburbs and the curvilinear complex of housing in the heights that accesses the waterfront business district via an elevated highway bypassing the Casbah. http://www.bidoun. com/issues/issue_ 6/05_all.html Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan Expressway project, 1970, and Hans Hollein (Austrian), Aircraft Carrier (original title is “Flugzeugträger,” 1964) 2 The Nimitz-class nuclear-powered aircraft carrier “Ronald Reagan” is 1,092 feet long, towering 20 stories above the waterline, home to 6,000 sailors, carrying more than 80 aircraft, with a 4.5 acre flight deck and a cruising speed in excess of 30 knots (34.5 mph). Archigram, Project for “A Walking City,” 1964 . 3 Peter Cook in 2004, with “Plug-In City” project and issue #4, “Archigram 4” . Archigram, “The Cushicle,” an portable, inflatable environment, 1965 4 Kisho Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower, 1972: 140 detachable spatial units joined to a central core for services and circulation Peter Cook, Museum of Contemporary Art, Graz, Austria, 2003 . -

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71St Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians

Papers Delivered in the Thematic Sessions of the 71st Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Saint Paul, Minnesota, 18–22 April 2018 All Ado About Bomarzo Architecture of Diplomacy and Defense Anatole Tchikine, Dumbarton Oaks, USA, Session Chair Cynthia G. Falk, State University of New York at Oneonta, USA, and Lisa P. Davidson, HABS—National Park Service, USA, “Landscape Architecture without Architects: Bomarzo and the Vernac- Session Co-Chairs ular,” Katherine Coty, University of Washington, USA “Cannibals, Grottoes and Vicino Orsini’s Sacro Bosco,” Luke Mor- “Building and Abandoning U.S. Naval Station Tutuila,” Kelema gan, Monash University, Australia Moses, Occidental College, USA “Botanicals and Symbolism in the Landscape of Bomarzo,” John “Border Stakes: Architecture as Diplomatic Tool in Contested Inter- Garton, Clark University, USA war Italo-Yugoslav Territories,” Matthew Worsnick, Institute of “‘Impressions so alien’: The Postwar Afterlife of the Sacro Fine Arts (NYU), USA Bosco,” Thalia Allington-Wood, University College “Architectural Mechanism of the Frontier Villages at the Korean London, UK Border,” Alex Young Il Seo, University of Cambridge, UK “Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden and the Legacies of Bomarzo,” “The Architecture of Peace in the Middle East,” Neta Feniger, John Beardsley, Dumbarton Oaks, USA Te c h n i o n —Israel Institute of Technology The Architecture of Commercial Networks, 1500–1900 Life to Architecture: Uncovering Women’s Narratives Katie Jakobiec, University of Oxford, -

Top Japanese Architects

TOP JAPANESE ARCHITECTS CURRENT VIEW OF JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE by Judit Taberna To be able to understand modern Japanese architecture we must put it into its historic context, and be aware of the great changes the country has undergone. Japan is an ancient and traditional society and a modern society at the same time. The explanation for this contradiction lies in the rapid changes resulting from the industrial and urban revolutions which began in Japan in the Meiji period and continued with renewed force in the years after the second world war. At the end of the nineteenth century, during the Meiji period, the isolation of the country which had lasted almost two centuries came abruptly to an end; it was the beginning of a new era for the Japanese who began to open up to the world. They began to study European and American politics and culture. Many Japanese architects traveled to Europe and America, and this led to the trend of European modernism which soon became a significant influence on Japanese architecture. With the Second World War the development in modern Japanese architecture ground to a halt, and it was not until a number of years later that the evolution continued. Maekawa and Sakura, the most well known architects at the time, worked with Le Corbusier and succeeded in combining traditional Japanese styles with modern architecture. However Kenzo Tange, Maekawa's disciple, is thought to have taken the first step in the modern Japanese movement. The Peace Center Memorial Museum at Hiroshima 1956, is where we can best appreciate his work.