Rhesus Macaque Eradication to Restore the Ecological Integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhesus Macaque Sequencing

White Paper for Complete Sequencing of the Rhesus Macaque (Macaca mulatta) Genome Jeffrey Rogers1, Michael Katze 2, Roger Bumgarner2, Richard A. Gibbs 3 and George M. Weinstock3 I. Introduction Humans are members of the Order Primates and our closest evolutionary relatives are other primate species. This makes primate models of human disease particularly important, as the underlying physiology and metabolism, as well as genomic structure, are more similar to humans than are other mammals. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are the animals most similar to humans in overall DNA sequence, with interspecies sequence differences of approximately 1- 1.5% (Stewart and Disotell 1998, Page and Goodman 2001). The other apes, including gorillas and orangutans are nearly as similar to humans. The animals next most closely related to humans are Old World monkeys, superfamily Cercopithecoidea. This group includes the common laboratory species of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), baboon (Papio hamadryas), pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina) and African green monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops). The human evolutionary lineage separated from the ancestors of chimpanzees about 6-7 million years ago (MYA), while the human/ape lineage diverged from Old World monkeys about 25 MYA (Stewart and Disotell 1998), and from another important primate group, the New World monkeys, more than 35-40 MYA. In comparison, humans diverged from mice and other non- primate mammals about 65-85 MYA (Kumar and Hedges 1998, Eizirik et al 2001). In the evaluation of primate candidates for genome sequencing there should be more to selection of an organism than evolutionary considerations. The chimpanzee’s status as Closest Relative To Human has earned it an exemption from this consideration. -

A Stepwise Male Introduction Procedure to Prevent Inbreeding in Naturalistic Macaque Breeding Groups

animals Article A Stepwise Male Introduction Procedure to Prevent Inbreeding in Naturalistic Macaque Breeding Groups Astrid Rox 1,2, André H. van Vliet 1, Jan A. M. Langermans 1,3,* , Elisabeth H. M. Sterck 1,2 and Annet L. Louwerse 1 1 Biomedical Primate Research Centre, Animal Science Department, 2288 GJ Rijswijk, The Netherlands; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (A.H.v.V.); [email protected] (E.H.M.S.); [email protected] (A.L.L.) 2 Animal Behaviour & Cognition (Formerly Animal Ecology), Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Utrecht University, 3508 TB Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 Department Population Health Sciences, Division Animals in Science and Society, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, 3584 CM Utrecht, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-152-842-620 Simple Summary: Housing of primates in groups increases animal welfare; however, this requires management to prevent inbreeding. To this end, males are introduced into captive macaque breeding groups, mimicking the natural migration patterns of these primates. However, such male introduc- tions can be risky and unsuccessful. The procedure developed by the Biomedical Primate Research Centre (BPRC), Rijswijk, the Netherlands, to introduce male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) into naturalistic social groups without a breeding male achieves relatively high success rates. Males are stepwise familiarized with and introduced to their new group, while all interactions between the new male and the resident females are closely monitored. Monitoring the behaviour of the resident Citation: Rox, A.; van Vliet, A.H.; females and their new male during all stages of the introduction provides crucial information as to Langermans, J.A.M.; Sterck, E.H.M.; whether or not it is safe to proceed. -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta) Recognize Group Membership Via Olfactory Cues Alone

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2015) 69:2019–2034 DOI 10.1007/s00265-015-2013-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) recognize group membership via olfactory cues alone Stefanie Henkel 1,2 & Angelina Ruiz Lambides1,3,4 & Anne Berger5 & Ruth Thomsen1,6,7 & Anja Widdig1,3 Received: 9 April 2015 /Revised: 18 September 2015 /Accepted: 21 September 2015 /Published online: 31 October 2015 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract The ability to distinguish group members from con- paradigm to investigate whether rhesus macaques (Macaca specifics living in other groups is crucial for gregarious spe- mulatta) can discriminate between body odors of female cies. Olfaction is known to play a major role in group recog- group members and females from different social groups. nition and territorial defense in a wide range of mammalian We conducted the study on the research island Cayo Santiago, taxa. Although primates have been typically regarded as Puerto Rico, in the non-mating season and controlled for kin- microsmatic (having a poor sense of smell), increasing evi- ship and familiarity using extensive pedigree and demograph- dence suggests that olfaction may play a greater role in pri- ic data. Our results indicate that both males and females in- mates’ social life than previously assumed. In this study, we spect out-group odors significantly longer than in-group carried out behavioral bioassays using a signaler-receiver odors. Males licked odors more often than females, and older animals licked more often than younger ones. Furthermore, individuals tended to place their nose longer towards odors Communicated by E. Huchard when the odor donor’s group rank was higher than the rank of Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article their own group. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

Macaca Fascicularis) in Thailand

The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University 8(2): 185-204, October 2008 ©2008 by Chulalongkorn University Current Situation and Status of Long-tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Thailand SUCHINDA MALAIVIJITNOND1* AND YUZURU HAMADA2 1Primate Research Unit, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand. 2Section of Morphology, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Inuyama, Japan. ABSTRACT.– Long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) are the most frequently encountered primate in Thailand. They are currently considered at low risk for extinction, however, they are threatened by habitat fragmentation or loss, inbreeding or outbreeding depression and hybridization. At present, no management measures have been taken and updated information on their situation and status are urgently needed. We sent questionnaires throughout Thailand to a total of 7,410 sub-districts, and received 1,417 (19.12%) replies. We traveled to the sub-districts from which the positive replies to questionnaires on macaques were obtained, from December 2002 to December 2007 and found long-tailed macaques in 74 locations which ranged from the lower northern and northeastern (ca. 16° 30´ N) to the southernmost part (ca. 6° 30´ N) of Thailand. The distribution of long-tailed macaques at present is similar to that reported 30 years ago, but their habitats have changed from natural forests to temples or recreation parks. On average, 200 monkeys per location were counted and some populations had more than 1,000 individuals. In some locations they were regarded as pests. Local authorities took short-term management measures such as translocation and contraception. Although many troops of Thai long- tailed macaques have inflated population densities, some local troops exhibited morphological, genetic and behavioural uniqueness that may be important to conserve. -

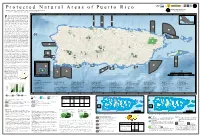

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

A Decade of Theory of Mind Research on Cayo Santiago: Insights Into Rhesus Macaque Social Cognition

American Journal of Primatology REVIEW ARTICLE A Decade of Theory of Mind Research on Cayo Santiago: Insights Into Rhesus Macaque Social Cognition LINDSEY A. DRAYTON* AND LAURIE R. SANTOS Psychology Department, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Over the past several decades, researchers have become increasingly interested in understanding how primates understand the behavior of others. One open question concerns whether nonhuman primates think about others’ behavior in psychological terms, that is, whether they have a theory of mind. Over the last ten years, experiments conducted on the free-ranging rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) living on Cayo Santiago have provided important insights into this question. In this review, we highlight what we think are some of the most exciting results of this body of work. Specifically we describe experiments suggesting that rhesus monkeys may understand some psychological states, such as what others see, hear, and know, but that they fail to demonstrate an understanding of others’ beliefs. Thus, while some aspects of theory of mind may be shared between humans and other primates, others capacities are likely to be uniquely human. We also discuss some of the broader debates surrounding comparative theory of mind research, as well as what we think may be productive lines for future research with the rhesus macaques of Cayo Santiago. Am. J. Primatol. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Key words: theory of mind; social cognition; rhesus macaques INTRODUCTION following a discussion of some of our own work, we Few people can observe nonhuman primates for examine some of the broader debates that surround any length of time without being struck by the this area of study and suggest what we believe will be richness of their social lives. -

4944941.Pdf (742.8Kb)

Phylogeny and History of the Lost SIV from Crab-Eating Macaques: SIVmfa The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McCarthy, Kevin R., Welkin E. Johnson, and Andrea Kirmaier. 2016. “Phylogeny and History of the Lost SIV from Crab- Eating Macaques: SIVmfa.” PLoS ONE 11 (7): e0159281. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0159281. Published Version doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159281 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:29002415 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA RESEARCH ARTICLE Phylogeny and History of the Lost SIV from Crab-Eating Macaques: SIVmfa Kevin R. McCarthy1,2☯¤, Welkin E. Johnson2, Andrea Kirmaier2☯* 1 Program in Virology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States of America, 2 Biology Department, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, United States of America ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ¤ Current address: Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, United States of America * [email protected] a11111 Abstract In the 20th century, thirteen distinct human immunodeficiency viruses emerged following independent cross-species transmission events involving simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) from African primates. In the late 1900s, pathogenic SIV strains also emerged in the United Sates among captive Asian macaque species following their unintentional infection OPEN ACCESS with SIV from African sooty mangabeys (SIVsmm). -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Fishes of the Western and Southwestern Coasts of Puerto Rico

Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 52(1), 1985, pp. 85-94 Digenetic Trematodes of Marine Fishes of the Western and Southwestern Coasts of Puerto Rico WILLIAM G. DYER,' ERNEST H. WILLIAMS, JR.,2 AND LUCY BUNKLEY WiLLiAMS2 1 Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 and 2 Department of Marine Science, University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico 00708 ABSTRACT: A comprehensive study was made in coastal waters of western and southwestern Puerto Rico from 1974 to 1984 to inventory the digenetic flukes of marine fishes. A total of 1,019 fishes representing 76 families, 155 genera, and 252 species were examined. Nineteen families of digenetic flukes representing 52 genera and 66 species were recorded, including 11 digenea not previously known from Puerto Rico. Four new host records were established. Most infections were of a single species and although prevalence and intensity were low, host specificity was high. Major contributions to knowledge of the di- The 66 species of flukes detected represented 19 genetic flukes of marine fishes of Puerto Rico families and 52 genera (Table 1). Of the 70 species stem from the early studies of Cable (1954a, b, of fishes that were infected, 56 (80%) harbored 1956a, b), LeZotte (1954), and the more recent 1 species of digenetic fluke, 8 species (11.4%) 2, comprehensive report by Siddiqi and Cable and 2 species (2.9%) with 3 to a maximum of 5 (1960). species of flukes. Fish negative for digeneans are Between April 1974 and January 1984 addi- listed in Appendix 1. tional data were obtained from examining 1,019 The intensity of a given species ranged from marine fishes representing 69 families of bony 1 to 100 flukes per host.