Evolutionary Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Anolis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla De Mona, P.R. by Ángel M

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla de Mona, P.R. by Ángel M. Nieves-Rivera, M.S. and Donald A. McFarlane, Ph.D. Isolobodon portoricensis, the extinct have been domesticated, and its abundant (14C) date was obtained on charcoal and Puerto Rican hutia (a large guinea-pig like remains in kitchen middens indicate that it bone fragments from Cueva Negra, rodent), was about the size of the surviving formed part of the diet for the early settlers associated with hutia bones (Frank, 1998). Hispaniolan hutia Plagiodontia (Rodentia: (Nowak, 1991; Flemming and MacPhee, This analysis yielded an uncorrected 14C age Capromydae). Isolobodon portoricensis was 1999). This species of hutia was extinct, of 380 ±60 before present, and a corrected originally reported from Cueva Ceiba (next apparently shortly after the coming of calendar age of 1525 AD, (1 sigma range to Utuado, P.R.) in 1916 by J. A. Allen (1916), European explorers, according to most 1480-1655 AD). This date coincides with the and it is known today only by skeletal remains historians. final occupation of Isla de Mona by the Taino from Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Haiti, The first person to take an interest in the Indians (1578 AD; Wadsworth 1977). The Île de la Gonâve, ÎIe de la Tortue), Puerto faunal remains of the caves of Isla de Mona purpose of this article is to report some new Rico (mainland, Isla de Mona, Caja de was mammalogist Harold E. Anthony, who paleontological discoveries of the Puerto Muertos, Vieques), the Virgin Islands (St. in 1926 collected the first Puerto Rican hutia Rican hutia in cave deposits of Isla de Mona Croix, St. -

Testing Sustainable Forestry Methods in Puerto Rico

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 141-148 (2015) (published online on 10 April 2015) Testing sustainable forestry methods in Puerto Rico: Does the presence of the introduced timber tree Blue Mahoe, Talipariti elatum, affect the abundance of Anolis gundlachi? Norman Greenhawk Abstract. The island of Puerto Rico has one of the highest rates of regrowth of secondary forests largely due to abandonment of previously agricultural land. The study was aimed at determining the impact of the presence of Talipariti elatum, a timber species planted for forest enrichment, on the abundance of anoles at Las Casas de la Selva, a sustainable forestry project located in Patillas, Puerto Rico. The trees planted around 25 years ago are fast-growing and now dominate canopies where they were planted. Two areas, a control area of second-growth forest without T. elatum and an area within the T. elatum plantation, were surveyed over an 18 month period. The null hypothesis that anole abundance within the study areas is independent of the presence of T. elatum could not be rejected. The findings of this study may have implications when designing forest management practices where maintaining biodiversity is a goal. Keywords. Anolis gundlachi, Anolis stratulus, Puerto Rican herpetofauna, introduced species, forestry Introduction The secondary growth forest represents a significant resource base for the people of Puerto Rico, and, if At the time of Spanish colonization in 1508, nearly managed properly, an increase in suitable habitat one hundred percent of Puerto Rico was covered in for forest-dwelling herpetofauna. Depending on the forest (Wadsworth, 1950). As a result of forest clearing management methods used, human-altered agro- for agricultural and pastureland, ship building, and fuel forestry plantations have potential conservation wood, approximately one percent of the land surface value (Wunderle, 1999). -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Chronology of Major Caribbean Earthquakes by Dr

Chronology of Major Caribbean Earthquakes By Dr. Frank J. Collazo February 4, 2010 Seismic Activity in the Caribbean Area The image above represents the earthquake activity for the past seven days in Puerto Rico (roughly Jan 8-15, 2010). As you can see there are quite a few recorded. In fact, the Puerto Rico Seismic Network has registered around 80 earthquake tremors in the first 15 days of 2010. Thankfully for Puerto Rico, these are usually on the lower end of the scale, but they are felt around the island. In fact, while being on the island, I actually felt two earthquakes, one of which was the 7.4 magnitude Martinique earthquake back in November 2007. The following is a chronology of the major earthquakes in the Caribbean basin: 1615: Earthquake in the Dominican Republic that caused damages in Puerto Rico. 1670: Damages in San Germán and San Juan (MJ). A strong earthquake, whose magnitude has not been determined, occurred in 1670, significantly affecting the area of San German District. 1692: Jamaica Fatalities 2,000. Level of damages is unknown. 1717: Church San Felipe in Arecibo and the parochial house in San Germán were destroyed (A). 1740: The Church of Guadalupe in Villa de Ponce was destroyed (A). Intensity VII, there is only information from Ponce that the earthquake was felt, absence of information of San Germán and the information of Yauco and Lajas suggest a superficial earthquake near to Ponce (G). 1787: Possibly the strongest earthquake that has affected Puerto Rico since the beginning of colonization. This was felt strongly throughout the Island and may have been as large as magnitude 8.0 on the Richter Scale. -

Phylogeny, Ecomorphological Evolution, and Historical Biogeography of the Anolis Cristatellus Series

Uerpetological Monographs, 18, 2004, 90-126 © 2004 by The Herpetologists' League, Inc. PHYLOGENY, ECOMORPHOLOGICAL EVOLUTION, AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ANOLIS CRISTATELLUS SERIES MATTHEW C. BRANDLEY^''^'"' AND KEVIN DE QUEIROZ^ ^Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Zoology, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072, USA ^Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20,560, USA ABSTRACT: TO determine the evolutionary relationships within the Anolis cristatellus series, we employed phylogenetic analyses of previously published karyotype and allozyme data as well as newly collected morphological data and mitochondrial DNA sequences (fragments of the 12S RNA and cytochrome b genes). The relationships inferred from continuous maximum likelihood reanalyses of allozyme data were largely poorly supported. A similar analysis of the morphological data gave strong to moderate support for sister relationships of the two included distichoid species, the two trunk-crown species, the grass-bush species A. poncensis and A. pulchellus, and a clade of trunk-ground and grass-bush species. The results of maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses of the 12S, cyt b, and combined mtDNA data sets were largely congruent, but nonetheless exhibit some differences both with one another and with those based on the morphological data. We therefore took advantage of the additive properties of likelihoods to compare alternative phylogenetic trees and determined that the tree inferred from the combined 12S and cyt b data is also the best estimate of the phylogeny for the morphological and mtDNA data sets considered together. We also performed mixed-model Bayesian analyses of the combined morphology and mtDNA data; the resultant tree was topologically identical to the combined mtDNA tree with generally high nodal support. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

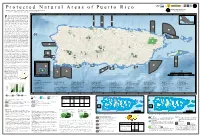

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

In the Face of Accelerating Habitat Loss and an Increasing Human

ABSTRACT Borkhataria, Rena Rebecca. Ecological and Political Implications of Conversion from Shade to Sun Coffee in Puerto Rico. (Under the direction of Jaime Collazo.) Recent studies have shown that biodiversity is greater in shaded plantations than in sun coffee plantations, yet many farmers are converting to sun coffee varieties to increase short-term yields or to gain access to economic incentives. Through conversion, ecosystem complexity may be reduced and ecological services rendered by inhabitants may be lost. I attempted to quantify differences in abundances and diversity of predators in sun and shade coffee plantations in Puerto Rico and to gain insight into the ecological services they might provide. I also interviewed coffee farmers to determine the factors influencing conversion to sun coffee in Puerto Rico and to examine their attitudes toward the conservation of wildlife. Avian abundances were significantly higher in shaded coffee than in sun (p = 0.01) as were the number of species (p = 0.09). Avian species that were significantly more abundant in shaded coffee tended to be insectivorous, whereas those in sun coffee were granivorous. Lizard abundances (all species combined) did not differ significantly between plantations types, but Anolis stratulus was more abundant in sun plantations and A. gundlachi and A. evermanni were present only in shaded plantations. Insect abundances (all species combined) were significantly higher in shaded coffee (p = 0.02). I used exclosures in a shaded coffee plantation to examine the effects of vertebrate predators on the arthropods associated with coffee, in particular the coffee leaf miner (Leucoptera coffeela) and the flatid planthopper Petrusa epilepsis, in a shaded coffee plantation in Puerto Rico. -

Predictability of Non-Phase-Locked Baroclinic Tides in the Caribbean Sea Edward D

Predictability of Non-Phase-Locked Baroclinic Tides in the Caribbean Sea Edward D. Zaron1 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon, USA Correspondence: E. D. Zaron ([email protected]) Abstract. The predictability of the sea surface height expression of baroclinic tides is examined with 96 hr forecasts pro- duced by the AMSEAS operational forecast model during 2013–2014. The phase-locked tide, both barotropic and baroclinic, is identified by harmonic analysis of the 2 year record and found to agree well with observations from tide gauges and satellite altimetry within the Caribbean Sea. The non-phase-locked baroclinic tide, which is created by time-variable mesoscale strati- 5 fication and currents, may be identified from residual sea level anomalies (SLAs) near the tidal frequencies. The predictability of the non-phase-locked tide is assessed by measuring the difference between a forecast – centered at T + 36 hr, T + 60 hr, or T + 84 hr – and the model’s later verifying analysis for the same time. Within the Caribbean Sea, where a baroclinic tidal sea level range of ±5 cm is typical, the forecast error for the non-phase-locked tidal SLA is correlated with the forecast error for the sub-tidal (mesoscale) SLA. Root-mean-square values of the former range from 0.5 cm to 2 cm, while the latter ranges from 10 1 cm to 6 cm, for a typical 84 hr forecast. The spatial and temporal variability of the forecast error is related to the dynamical origins of the non-phase-locked tide and is briefly surveyed within the model. -

Anidación De La Tortuga Carey (Eretmochelys Imbricata) En Isla De Mona, Puerto Rico

Anidación de la tortuga carey (Eretmochelys imbricata) en Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Carlos E. Diez 1, Robert P. van Dam 2 1 DRNA-PR PO Box 9066600 Puerta de Tierra San Juan, PR 00906 [email protected] 2 Chelonia Inc PO Box 9020708 San Juan, PR 00902 [email protected] Palabras claves: Reptilia, carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, anidación, tortugas marinas, marcaje, conservación, Caribe, Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Resumen El carey de concha, Eretmochelys imbricata, es la especie de tortuga marina más abundante en nuestras playas y costas. Sin embargo está clasificada como una especie en peligro de extinción por leyes estatales y federales además de estar protegida a nivel internacional. Uno de los lugares más importantes del Caribe para la reproducción de esta especie es en la Isla de Mona, Puerto Rico. Los resultados del monitoreo de la actividad de anidaje en la Isla de Mona han demostrado un incremento siginificativo en el números de nidos de la tortuga carey depositado en la isla durante los últimos años. En el año 2005 se contó un total de 1003 nidos de carey depositados en todas las playas de Isla de Mona durante 116 días de monitoreo, lo cual es una cantidad mayor que durante cualquier censo en años anteriores (en 1994 se contaron 308 nidos depositados en 114 días). De igual manera, el Índice de Actividades de Anidaje cual esta basado en conteos precisos durante 60 dias aumento a partir de su estableciemiento en el 2003 con 298 nidos de carey con 18% a 353 nidos en 2004 y resultando en 368 nidos en el 2005.