ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Report Reporting Period: June 2019 Reference: MR/6/2019 Date: 13 July 2019

Monthly Report Reporting Period: June 2019 Reference: MR/6/2019 Date: 13 July 2019 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bvirecovery.vg Third Floor, Ritter House, Wickham’s Cay II, Tortola VG1110, Virgin Islands Table of Acronyms BOQ Bill of Quantities BVI-EC British Virgin Islands Electricity Corporation DWM Department of Waste Management ITT Invitation to Tender JVD Jost Van Dyke MECYAFA Ministry of Education, Culture, Youth Affairs, Fisheries & Agriculture MTWU Ministry of Transportation, Works & Utilities MHSD Ministry of Health and Social Development MNRLI Ministry of Natural Resources, Labour and Immigration RE Renewable Energy RDA Recovery and Development Agency RDP Recovery to Development Plan RVIPF Royal Virgin Islands Police Force SoR Statement of Requirement ToR Terms of Reference Monthly Report – June 2019 bvirecovery.vg 0 Table of Contents Project Status Update.................................................................................................................................... 2 Communications ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Fundraising .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Annex I: Project Updates ............................................................................................................................. 12 Annex II: Completed Projects ..................................................................................................................... -

Testing Sustainable Forestry Methods in Puerto Rico

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 141-148 (2015) (published online on 10 April 2015) Testing sustainable forestry methods in Puerto Rico: Does the presence of the introduced timber tree Blue Mahoe, Talipariti elatum, affect the abundance of Anolis gundlachi? Norman Greenhawk Abstract. The island of Puerto Rico has one of the highest rates of regrowth of secondary forests largely due to abandonment of previously agricultural land. The study was aimed at determining the impact of the presence of Talipariti elatum, a timber species planted for forest enrichment, on the abundance of anoles at Las Casas de la Selva, a sustainable forestry project located in Patillas, Puerto Rico. The trees planted around 25 years ago are fast-growing and now dominate canopies where they were planted. Two areas, a control area of second-growth forest without T. elatum and an area within the T. elatum plantation, were surveyed over an 18 month period. The null hypothesis that anole abundance within the study areas is independent of the presence of T. elatum could not be rejected. The findings of this study may have implications when designing forest management practices where maintaining biodiversity is a goal. Keywords. Anolis gundlachi, Anolis stratulus, Puerto Rican herpetofauna, introduced species, forestry Introduction The secondary growth forest represents a significant resource base for the people of Puerto Rico, and, if At the time of Spanish colonization in 1508, nearly managed properly, an increase in suitable habitat one hundred percent of Puerto Rico was covered in for forest-dwelling herpetofauna. Depending on the forest (Wadsworth, 1950). As a result of forest clearing management methods used, human-altered agro- for agricultural and pastureland, ship building, and fuel forestry plantations have potential conservation wood, approximately one percent of the land surface value (Wunderle, 1999). -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

VISR Template Letter 0709

Virgin Islands Shipping Registry Sebastian’s Building, PO Box 4751, Road Town, Tortola, British Virgin Islands, VG1110 Tel: +1 284 468 2902/2903 Fax: +1 284 468 2913 Duty Officer: +1 284 468 9646 Website: www.vishipping.gov.vg General Email: [email protected] SAFETY ALERT NOTICE TO MARINERS No.2/2015 Applicability: All vessels in Virgin Islands waters Date of Issue: 06 February 2015 North Coast Virgin Gorda - Transiting North Sound and Eustatia Sound In the North Coast of Virgin Gorda, in the North Sound and Eustatia Sound there are a number of resorts. The area is considered as one of BVI’s “Natures Little Secrets” and is a playground for recreational activities such as swimming, snorkelling, stand up paddle boarding, windsurfing, kite boarding etc. The Blunder Bay area from the Anguilla Point to Little Leverick Bay and the buoyed channel between North Sound and Eustatia Sound is a NO WAKE ZONE and has SPEED LIMIT 5 Knots. It has been brought to our attention that many vessels in transit ignore these restrictions and proceed at very high speed. The wake created by these large vessels and speeding powerboats is eroding the beaches and making water based recreational activities dangerous. It is important to note that the vessels MUST transit the area at such a speed that NO WAKE is generated by them. This means that larger vessels with higher draught and displacement such as cargo ships, barges and mega yachts may have to proceed at a speed lower than 5 Knots in order to create NO WAKE during their passage. -

Caribbean Anolis Lizards

Animal Behaviour 85 (2013) 1415e1426 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Convergent evolution in the territorial communication of a classic adaptive radiation: Caribbean Anolis lizards Terry J. Ord a,*, Judy A. Stamps b, Jonathan B. Losos c a Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, and School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia b Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA, U.S.A. c Museum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A. article info To demonstrate adaptive convergent evolution, it must be shown that shared phenotypes have evolved Article history: independently in different lineages and that a credible selection pressure underlies adaptive evolution. Received 11 December 2012 There are a number of robust examples of adaptive convergence in morphology for which both these Initial acceptance 4 February 2013 criteria have been met, but examples from animal behaviour have rarely been tested as rigorously. Final acceptance 15 March 2013 Adaptive convergence should be common in behaviour, especially behaviour used for communication, Available online 3 May 2013 because the environment often shapes the evolution of signal design. In this study we report on the origins MS. number: A12-00933 of a shared design of a territorial display among Anolis species of lizards from two island radiations in the Caribbean. These lizards perform an elaborate display that consists of a complex series of headbobs and Keywords: dewlap extensions. The way in which these movements are incorporated into displays is generally species adaptation specific, but species on the islands of Jamaica and Puerto Rico also share fundamental aspects in display Anolis lizard design, resulting in two general display types. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards

Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046431 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards A dissertation presented by Ambika Kamath to The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2017 © 2017 Ambika Kamath All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Jonathan Losos Ambika Kamath Phenotypic Variation and the Behavioral Ecology of Lizards Abstract Behavioral ecology is the study of how animal behavior evolves in the context of ecology, thus melding, by definition, investigations of how social, ecological, and evolutionary forces shape phenotypic variation within and across species. Framed thus, it is apparent that behavioral ecology also aims to cut across temporal scales and levels of biological organization, seeking to explain the long-term evolutionary trajectory of populations and species by understanding short-term interactions at the within-population level. In this dissertation, I make the case that paying attention to individuals’ natural history— where and how individual organisms live and whom and what they interact with, in natural conditions—can open avenues into studying the behavioral ecology of previously understudied organisms, and more importantly, recast our understanding of taxa we think we know well. -

Phylogeny, Ecomorphological Evolution, and Historical Biogeography of the Anolis Cristatellus Series

Uerpetological Monographs, 18, 2004, 90-126 © 2004 by The Herpetologists' League, Inc. PHYLOGENY, ECOMORPHOLOGICAL EVOLUTION, AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ANOLIS CRISTATELLUS SERIES MATTHEW C. BRANDLEY^''^'"' AND KEVIN DE QUEIROZ^ ^Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Zoology, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072, USA ^Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20,560, USA ABSTRACT: TO determine the evolutionary relationships within the Anolis cristatellus series, we employed phylogenetic analyses of previously published karyotype and allozyme data as well as newly collected morphological data and mitochondrial DNA sequences (fragments of the 12S RNA and cytochrome b genes). The relationships inferred from continuous maximum likelihood reanalyses of allozyme data were largely poorly supported. A similar analysis of the morphological data gave strong to moderate support for sister relationships of the two included distichoid species, the two trunk-crown species, the grass-bush species A. poncensis and A. pulchellus, and a clade of trunk-ground and grass-bush species. The results of maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses of the 12S, cyt b, and combined mtDNA data sets were largely congruent, but nonetheless exhibit some differences both with one another and with those based on the morphological data. We therefore took advantage of the additive properties of likelihoods to compare alternative phylogenetic trees and determined that the tree inferred from the combined 12S and cyt b data is also the best estimate of the phylogeny for the morphological and mtDNA data sets considered together. We also performed mixed-model Bayesian analyses of the combined morphology and mtDNA data; the resultant tree was topologically identical to the combined mtDNA tree with generally high nodal support. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

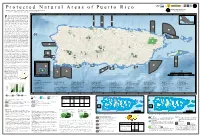

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

(A) PUERTO RICO - Large Scale Characteristics

(a) PUERTO RICO - Large scale characteristics Although corals grow around much of Puerto Rico, physical conditions result in only localized reef formation. On the north coast, reef development is almost non-existent along the western two-thirds possibly as a result of one or more of the following factors: high rainfall; high run-off rates causing erosion and silt-laden river waters; intense wave action which removes suitable substrate for coral growth; and long shore currents moving material westward along the coast. This coast is steep, with most of the island's land area draining through it. Reef growth increases towards the east. On the wide insular shelf of the south coast, small reefs are found in abundance where rainfall is low and river influx is small, greatest development and diversity occurring in the southwest where waves and currents are strong. There are also a number of submerged reefs fringing a large proportion of the shelf edge in the south and west with high coral cover and diversity; these appear to have been emergent reefs 8000-9000 years ago which failed to keep pace with rising sea levels (Goenaga in litt. 7.3.86). Reefs on the west coast are limited to small patch reefs or offshore bank reefs and may be dying due to increased sediment influx, water turbidity and lack of strong wave action (Almy and Carrión-Torres, 1963; Kaye, 1959). Goenaga and Cintrón (1979) provide an inventory of mainland Puerto Rican coral reefs and the following is a brief summary of their findings. On the basis of topographical, ecological and socioeconomic characteristics, Puerto Rico's coastal perimeter can be divided into eight coastal sectors -- north, northeast, southeast, south, southwest, west, northwest, and offshore islands. -

British Virgin Islands

THE NATIONAL REPORT EL REPORTE NACIONAL FOR THE COUNTRY OF POR EL PAIS DE BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVE / REPRESENTANTE NACIONAL LOUIS WALTERS Western Atlantic Turtle Symposium Simposio de Tortugas del Atlantico Occidental 17-22 July / Julio 1983 San José, Costa Rica BVI National Report, WATS I Vol 3, pages 70-117 WESTERN ATLANTIC TURTLE SYMPOSIUM San José, Costa Rica, July 1983 NATIONAL REPORT FOR THE COUNTRY OF BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL REPORT PRESENTED BY Louis Walters The National Representative Address: Permanent Secretary, Ministry of National Resources and Environment Tortola, British Virgin Islands NATIONAL REPORT PREPARED BY John Fletemeyer DATE SUBMITTED: 2 June 1983 Please submit this NATIONAL REPORT no later than 1 December 1982 to: IOC Assistant Secretary for IOCARIBE ℅ UNDP, Apartado 4540 San José, Costa Rica BVI National Report, WATS I Vol 3, pages 70-117 With a grant from the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, WIDECAST has digitized the data- bases and proceedings of the Western Atlantic Turtle Symposium (WATS) with the hope that the revitalized documents might provide a useful historical context for contemporary sea turtle management and conservation efforts in the Western Atlantic Region. With the stated objective of serving “as a starting point for the identification of critical areas where it will be necessary to concentrate all efforts in the future”, the first Western Atlantic Turtle Sym- posium convened in Costa Rica (17-22 July 1983), and the second in Puerto Rico four years later (12-16 October 1987). WATS I featured National Reports from 43 political jurisdictions; 37 pre- sented at WATS II.