Survival Analysis of Two Endemic Lizard Species Before, During and After a Rat Eradication Attempt on Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predation on Ameiva Ameiva (Squamata: Teiidae) by Ardea Alba (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae) in the Southwestern Brazilian Amazon

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 1073-1075 (2021) (published online on 10 August 2021) Predation on Ameiva ameiva (Squamata: Teiidae) by Ardea alba (Pelecaniformes: Ardeidae) in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon Raul A. Pommer-Barbosa1,*, Alisson M. Albino2, Jessica F.T. Reis3, and Saara N. Fialho4 Lizards and frogs are eaten by a wide range of wetlands, being found mainly in lakes, wetlands, predators and are a food source for many bird species flooded areas, rivers, dams, mangroves, swamps, in neotropical forests (Poulin et al., 2001). However, and the shallow waters of salt lakes. It is a species predation events are poorly observed in nature and of diurnal feeding habits, but its activity peak occurs hardly documented (e.g., Malkmus, 2000; Aguiar and either at dawn or dusk. This characteristic changes Di-Bernardo, 2004; Silva et al., 2021). Such records in coastal environments, where its feeding habit is are certainly very rare for the teiid lizard Ameiva linked to the tides (McCrimmon et al., 2020). Its diet ameiva (Linnaeus, 1758) (Maffei et al., 2007). is varied and may include amphibians, snakes, insects, Found in most parts of Brazil, A. ameiva is commonly fish, aquatic larvae, mollusks, small crustaceans, small known as Amazon Racerunner or Giant Ameiva, and birds, small mammals, and lizards (Martínez-Vilalta, it has one of the widest geographical distributions 1992; Miranda and Collazo, 1997; Figueroa and among neotropical lizards. It occurs in open areas all Corales Stappung, 2003; Kushlan and Hancock 2005). over South America, the Galapagos Islands (Vanzolini We here report a predation event on the Ameiva ameiva et al., 1980), Panama, and several Caribbean islands by Ardea alba in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon. -

Helminths from Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) at the Cerrado of Goiás State, Brazil Author(S): Robson W

Helminths from Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) at the Cerrado of Goiás State, Brazil Author(s): Robson W. Ávila, Manoela W. Cardoso, Fabrício H. Oda, and Reinaldo J. da Silva Source: Comparative Parasitology, 78(1):120-128. 2011. Published By: The Helminthological Society of Washington DOI: 10.1654/4472.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1654/4472.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Comp. Parasitol. 78(1), 2011, pp. 120–128 Helminths from Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) at the Cerrado of Goia´s State, Brazil 1,4 2 3 1 ROBSON W. A´ VILA, MANOELA W. CARDOSO, FABRI´CIO H. ODA, AND REINALDO J. DA SILVA 1 Departamento de Parasitologia, Instituto de Biocieˆncias, UNESP, Distrito de Rubia˜o Jr., CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, SP, Brazil, 2 Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, CEP 20940- 040, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, and 3 Universidade Federal de Goia´s–UFG, Laborato´rio de Comportamento Animal, Instituto de Cieˆncias Biolo´gicas, Campus Samambaia, Conjunto Itatiaia, CEP 74000-970. -

FOOD HABITS of the LIZARD Ameiva Ameiva (LINNAEUS, 1758) (SAURIA: TEIIDAE) in a TROPOPHIC FOREST of SUCRE STATE, VENEZUELA

Acta Biol. Venez.Vol. 28 (2): 53-59. Junio-Diciembre, 2008 FOOD HABITS OF THE LIZARD Ameiva ameiva (LINNAEUS, 1758) (SAURIA: TEIIDAE) IN A TROPOPHIC FOREST OF SUCRE STATE, VENEZUELA. HÁBITOS ALIMENTARIOS DEL LAGARTO Ameiva ameiva (LINNAEUS, 1758) (SAURIA: TEIIDAE) EN UN BOSQUE TROPÓFILO DEL ESTADO SUCRE, VENEZUELA. Luis Alejandro González S. 1-2, Jenniffer Velásquez2, Hernán Ferrer3, James García1, Francia Cala1 and José Peñuela1 1- Departamento de Biología, Laboratorio de Ecología Animal, Universidad de Oriente, Cumaná, Venezuela. ([email protected]); 2. Posgrado de Zoología, Instituto de Zoología Tropical, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Central de Venezuela ([email protected]); 3. Gerencia de Investigación y Desarrollo, Jardín Botánico de Caracas, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela ([email protected]). ABSTRACT Food habits among sexes of Ameiva ameiva were evaluated by the frequency of occurrence, trophic dominance, and diet similarity methods during periods of rain and drought in a tropophic forest in La Llanada Vieja, Sucre State, Venezuela. 431 prey items were identified in 20 stomachs analyzed. Diet for both periods showed a high frequency for Coleoptera, plant material, Isoptera, Nematoda, Araneae, and reptilian rests. Males and females showed differences in diet during the climatic periods analyzed. Females showed higher stomach volumes values than males. Results suggest the species is mainly insectivorous. RESUMEN Se evaluaron los hábitos alimentarios de Ameiva ameiva, mediante el método de frecuencia de aparición, dominancia trófica y similitud de la dieta entre sexos, abarcando los periodos de lluvia y sequía. La captura se realizó en un bosque tropófilo de los alrededores de la Llanada Vieja, estado Sucre, Venezuela. -

Two New Scorpions from the Puerto Rican Island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae)

Two new scorpions from the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, Greater Antilles (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Carlos J. Santos September 2015 — No. 208 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Us Caribbean Regional Coral Reef Fisheries Management Workshop

Caribbean Regional Workshop on Coral Reef Fisheries Management: Collaboration on Successful Management, Enforcement and Education Methods st September 30 - October 1 , 2002 Caribe Hilton Hotel San Juan, Puerto Rico Workshop Objective: The regional workshop allowed island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to identify successful coral reef fishery management approaches. The workshop provided the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force with recommendations by local, regional and national stakeholders, to develop more effective and appropriate regional planning for coral reef fisheries conservation and sustainable use. The recommended priorities will assist Federal agencies to provide more directed grant and technical assistance to the U.S. Caribbean. Background: Coral reefs and associated habitats provide important commercial, recreational and subsistence fishery resources in the United States and around the world. Fishing also plays a central social and cultural role in many island communities. However, these fishery resources and the ecosystems that support them are under increasing threat from overfishing, recreational use, and developmental impacts. This workshop, held in conjunction with the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force Meeting, brought together island resource managers, fisheries educators and enforcement personnel to compare methods that have been successful, including regulations that have worked, effective enforcement, and education to reach people who can really effect change. These efforts were supported by Federal fishery managers and scientists, Puerto Rico Sea Grant, and drew on the experience of researchers working in the islands and Florida. The workshop helped develop approaches for effective fishery management strategies in the U.S. Caribbean and recommended priority actions to the U.S. -

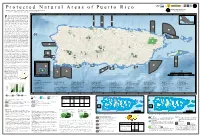

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Ameiva Ameiva (Zandolie Or Jungle Runner)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Ameiva ameiva (Zandolie or Jungle Runner) Family: Teiidae (Tegus and Whiptails) Order: Squamata (Lizards and Snakes) Class: Reptilia (Reptiles) Fig. 1. Zandolie, Ameiva ameiva. [https://c2.staticflickr.com/4/3804/13311081294_c5a2cfcfc8_b.jpg, downloaded 29 March 2015] TRAITS. Ameiva ameiva lizards are large bodied, streamlined in shape, their heads are pointed and their tongues are slightly forked. Their legs are short and their hind legs are very muscular (Fig. 1). These lizards display sexual dimorphism. The female body length is approximately 49cm and the male 56 cm (ttfnc.org, 2006). The males are larger than the females in size, their backs are dull green and their flanks are colourful, whereas the females are quite similar but they have much brighter green backs (Kenny, 2008). The males also have relatively larger heads than the females (Colli and Vitt, 1994). Juveniles have relatively large heads for their body size. Ameiva ameiva is also called the jungle runner or giant ameiva (Myfwc.com, 2015). DISTRIBUTION. According to Animal Diversity Web (2014), Ameiva ameiva is found in Central and South America and in some parts of the Caribbean. Countries include; Brazil, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Colombia and many others. UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. They are diurnal, found in open tropical forests, woodlands and agricultural land (Anapsid.org, 1995), in open, sunny, grassy areas. Biazquez (1996) says that both adults and juveniles liked sunny areas and they spend most of their time foraging and basking. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Rhesus Macaque Eradication to Restore the Ecological Integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico

C.C. Hanson, T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell Hanson, C.C.; T.J. Hall, A.J. DeNicola, S. Silander, B.S. Keitt and K.J. Campbell. Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico Rhesus macaque eradication to restore the ecological integrity of Desecheo National Wildlife Refuge, Puerto Rico C.C. Hanson¹, T.J. Hall¹, A.J. DeNicola², S. Silander³, B.S. Keitt¹ and K.J. Campbell1,4 ¹Island Conservation, 2100 Delaware Ave. Suite 1, Santa Cruz, California, 95060, USA. <chad.hanson@ islandconservation.org>. ²White Buff alo Inc., Connecticut, USA. ³U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Caribbean Islands› NWR, P.O. Box 510 Boquerón, 00622, Puerto Rico. 4School of Geography, Planning & Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia. Abstract A non-native introduced population of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) was targeted for removal from Desecheo Island (117 ha), Puerto Rico. Macaques were introduced in 1966 and contributed to several plant and animal extirpations. Since their release, three eradication campaigns were unsuccessful at removing the population; a fourth campaign that addressed potential causes for previous failures was declared successful in 2017. Key attributes that led to the success of this campaign included a robust partnership, adequate funding, and skilled fi eld staff with a strong eradication ethic that followed a plan based on eradication theory. Furthermore, the incorporation of modern technology including strategic use of remote camera traps, monitoring of radio-collared Judas animals, night hunting with night vision and thermal rifl e scopes, and the use of high-power semi-automatic fi rearms made eradication feasible due to an increase in the probability of detection and likelihood of removal. -

Mjie,Ianjfuseum

MJie,ianJfuseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1934 APRIL 22, 1959 Taxonomic Notes on a Collection of Venezuelan Reptiles in the American Museum of Natural History BY JANIS A. ROZE1 INTRODUCTION While visiting museums2 in the United States in an effort to prepare a monographic study of the Venezuelan snake fauna, I had the privi- lege of examining an unidentified reptile collection in the American Museum of Natural History. It contained 72 specimens, representing 25 species and subspecies, two of which proved to be undescribed. Notes on specimens from the United States National Museum (U.S.N.M.), Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh (C.M.), and Museo de Biologia, Univer- sidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela (M.B.U.C.V.), are added. At present the state of our knowledge concerning the systematic position of the amphibians and reptiles, or, indeed, the flora and fauna, of South America in general and Venezuela in particular leaves much to be desired. The situation here is similar to the one existing about 50 to 70 years ago in Europe or North America; thus every speci- men collected contributes to our understanding of the various popula- tions within a given area, or discloses the existence of taxa not pre- ' Escuela de Biologia, Universidad Central de Venezuela. 2 The trip was financed by the Fundaci6n Creole, Caracas, Venezuela, and the Council Research Fund of the American Museum of Natural History. 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. 1934 viously recognized. Not until rather exhaustive taxonomic studies have been completed can the zoogeographical and ecological problems be fully appreciated and worked out in detail. -

Haematozoan Parasites of the Lizard Ameiva Ameiva (Teiidae) from Amazonian Brazil: a Preliminary Note Ralph Lainson+, Manoel C De Souza, Constância M Franco

Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 98(8): 1067-1070, December 2003 1067 Haematozoan Parasites of the Lizard Ameiva ameiva (Teiidae) from Amazonian Brazil: a Preliminary Note Ralph Lainson+, Manoel C de Souza, Constância M Franco Departamento de Parasitologia, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Av. Almirante Barroso 492, 66090-000 Belém, PA, Brasil Three different haematozoan parasites are described in the blood of the teiid lizard Ameiva ameiva Linn. from North Brazil: one in the monocytes and the other two in erythrocytes. The leucocytic parasite is probably a species of Lainsonia Landau, 1973 (Lankesterellidae) as suggested by the presence of sporogonic stages in the internal organs, morphology of the blood forms (sporozoites), and their survival and accumulation in macrophages of the liver. One of the erythrocytic parasites produces encapsulated, stain-resistant forms in the peripheral blood, very similar to gametocytes of Hemolivia Petit et al., 1990. The other is morphologically very different and characteristically adheres to the host-cell nucleus. None of the parasites underwent development in the mosquitoes Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti and their behaviour in other haematophagous hosts is under investigation. Mixed infections of the parasites commonly occur and this often creates difficulties in relating the tissue stages in the internal organs to the forms seen in the blood. Concomitant infections with a Plasmodium tropiduri-like malaria parasite were seen and were sometimes extremely heavy. Key words: Ameiva ameiva - lizards - haematozoa - haemogregarines - Lainsonia - Hemolivia - tissue stages - Brazil Species of Ameiva (Reptilia: Squamata: Teiidae) are number of tissue stages seen in the viscera which offer common terrestrial lizards, widely distributed in Central an indication regarding the taxonomy of two of the pa- and South America and the Antilles.