Chaim Waxman American Jewish Philanthropy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing a Dvar Torah

PREPARING A DVAR TORAH GUIDELINES AND RESOURCES Preparing a dvar Torah 1 Preparing a dvar Torah 2 Preparing a dvar Torah 1 MANY PEOPLE WHO ARE ASKED TO GIVE a dvar Torah don't know where to begin. Below are some simple guidelines and instructions. It is difficult to provide a universal recipe because there are many different divrei Torah models depending on the individual, the context, the intended audience and the weekly portion that they are dealing with! However, regardless of content, and notwithstanding differences in format and length, all divrei Torah share some common features and require similar preparations. The process is really quite simple- although the actual implementation is not always so easy. The steps are as follows: Step One: Understand what a dvar Torah is Step Two: Choose an issue or topic (and how to find one) Step Three: Research commentators to explore possible solutions Step Four: Organize your thoughts into a coherent presentation 1Dvar Torah: literallly, 'a word of Torah.' Because dvar means 'a word of...' (in the construct form), please don't use the word dvar without its necessary connected direct object: Torah. Instead, you can use the word drash, which means a short, interpretive exposition. Preparing a dvar Torah 3 INTRO First clarify what kind of dvar Torah are you preparing. Here are three common types: 1. Some shuls / minyanim have a member present a dvar Torah in lieu of a sermon. This is usually frontal (ie. no congregational response is expected) and may be fifteen to twenty minutes long. 2. Other shuls / minyanim have a member present a dvar Torah as a jumping off point for a discussion. -

Judaism 2.0: Identity

ph A ogr N Judaism 2.0: identity, ork Mo philanthrophy W and the Net S new media der N u F h S i W A Je 150 West 30th Street, Suite 900 New York, New York 10001 212.726.0177 Fax 212.594.4292 [email protected] www.jfunders.org BY Gail Hyman ph A the (JFN) Jewish Funders network ogr is an international organization N udaism 2.0: of family foundations, public J philanthropies, and individual identity, ork Mo funders dedicated to advancing the W philanthrophy quality and growth of philanthropy and the Net rooted in Jewish values. JFN’s S new media members include independent der N philanthropists, foundation trustees u F and foundation professionals— h S a unique community that seeks i W to transform the nature of Jewish giving in both thought and action. A Je special acknowledgement the Jewish Funders network thanks the andrea and charles Bronfman philanthropies for its support of this Judaism 2.0: identity, philanthrophy and the new media. we are very grateful to Jeffrey solomon and roger Bennett, of ACBp, who were instrumental in conceiving the project, offering guidance, critique and encouragement along the way. we also thank Jos thalheimer, who provided research support throughout the project. we are also grateful that the Jewish Funders network was given the opportunity to publish this monograph and share its important insights about the role of the Jewish BY Gail Hyman community in the emerging digital communications age. JUDAISm 2.0: iDEnTiTy, PHILANTHROPHy a JEWiSH FUnders network AND THE nEW mEDIA mOnograph 2007 According to the pew internet future, and yet they, like most of the philanthropic world, are Adoption rate Survey, internet penetration among American falling behind when it comes to the new media. -

In the Educational Philosophy of Limmud

INDIVIDUALS PRACTISING COMMUNITY: THE CENTRAL PLACE OF INTERACTION IN THE EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY OF LIMMUD JONATHAN BOYD, BA (HaNS), MA THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION APRIL2013 ABSTRACT In light of growing evidence of exogamy among Jews and diminishing levels of community engagement, the question of how to sustain and cultivate Jewish identity has become a major preoccupation in the Jewish world since the early 1990s. Among the numerous organisations, programmes and initiatives that have been established and studied in response, Limmud, a week-long annual festival of Jewish life and learning in the UK that attracts an estimated 2,500 people per annum and has been replicated throughout the world, remains decidedly under-researched. This study is designed to understand its educational philosophy. Based upon qualitative interviews with twenty Limmud leaders, and focus group sessions with Limmud participants, it seeks to explore the purposes of the event, its content, its social and educational processes, and contextual environment. It further explores the importance of relationships in Limmud's philosophy, and the place of social capital in its practice. The study demonstrates that Limmud's educational philosophy is heavily grounded in the interaction of competing tensions, or polarities, on multiple levels. Major categorical distinctions drawn in educational philosophy and practice, and Jewish and general sociology, are both maintained and allowed to interact. This interaction takes place in a "hospitable and charged" environment - one that is simultaneously safe, respectful and comfortable, whilst also edgy, powerful and challenging - that allows the individual freedom to explore and navigate the contours of Jewish community, and the Jewish community opportunity to envelope and nurture the experience of the individual. -

REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed?

The iEngage Project of The Shalom Hartman Institute Jerusalem, Israel | June 2013 REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed? Jewish journalists and the media they work for are at a crossroads. As both their audiences and the technologies they use are changing rapidly, Jewish media journalists remain committed and optimistic, yet they face challenges as great as any in the 300-year history of the Jewish press. ALAN D. ABBEY REPORTING JEWISH: Do Journalists Have the Tools to Succeed? ALAN D. ABBEY The iEngage Project of the Shalom Hartman Institute http://iengage.org.il http://hartman.org.il Jerusalem, Israel June 2013 The iEngage Project of The Shalom Hartman Institute TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………........…………………..4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………….....……………………...…...6 Key Findings………………………………………………………………………………..……6 Key Recommendations………………………………………………………………………….7 HISTORY OF THE JEWISH MEDIA……………………...……………………….8 Journalists and American Jews – Demographic Comparisons………………………………….12 JEWISH IDENTITY AND RELIGIOUS PRACTICE…………………………….14 Journalism Experience and Qualifications…………………………………………………….15 HOW JOURNALISTS FOR JEWISH MEDIA VIEW AND ENGAGE WITH ISRAEL……………………………………………….16 Knowledge of Israel and Connection to Israel…………………………………………...…….18 Criticism of Israel: Is It Legitimate?………………….………….…………………………..…….19 Issues Facing Israel…………………………………………………….…………………...….21 Journalism Ethics and the Jewish Journalist………………………………………..…….22 Activism and Advocacy among Jewish Media Journalists...…….......………………….26 -

Reinventing American Jewish Identity Through Hip Hop

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2009-2010: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Connections Research Fellows 4-2010 Sampling the Shtetl: Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop Meredith R. Aska McBride University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2010 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Aska McBride, Meredith R., "Sampling the Shtetl: Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop" (2010). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2009-2010: Connections. 1. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2010/1 Suggested Citation: Aska McBride, Meredith. (2010). "Sampling the Shtetl: Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop." 2009-2010 Penn Humanities Forum on Connections. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2010/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sampling the Shtetl: Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop Disciplines Arts and Humanities Comments Suggested Citation: Aska McBride, Meredith. (2010). "Sampling the Shtetl: Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop." 2009-2010 Penn Humanities Forum on Connections. This other is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2010/1 0 Sampling the Shtetl Reinventing American Jewish Identity through Hip Hop Meredith R. Aska McBride 2009–2010 Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Mellon Research Fellowship Penn Humanities Forum Mellon Undergraduate Research Fellowship, -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMTPON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Modern Languages Perceptions of Holocaust Memory: A Comparative study of Public Reactions to Art about the Holocaust at the Jewish Museum in New York and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (1990s-2000s) by Diana I. Popescu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHMAPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Modern Languages Doctor of Philosophy PERCEPTIONS OF HOLOCAUST MEMORY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PUBLIC REACTIONS TO ART EXHIBITIONS ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST AT THE JEWISH MUSEUM IN NEW YORK AND THE ISRAEL MUSEUM IN JERUSALEM (1990s-2000s) by Diana I. Popescu This thesis investigates the changes in the Israeli and Jewish-American public perception of Holocaust memory in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and offers an elaborate comparative analysis of public reactions to art about the Holocaust. -

Jews and Power: Literature, Philosophy, Politics December 1, 2014

THE TIKVAH FUND 165 E. 56th Street New York, New York 10022 Jews and Power: Literature, Philosophy, Politics December 1, 2014 – December 12, 2014 Participant Biographies Benjamin Bilski Netherlands Benjamin Bilski is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Pericles Foundation. Benjamin is a Ph.D. candidate at the Institute of the Interdisciplinary Study of the Law, Faculty of Law of the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. He is working as author and editor with The Owls Foundation on a new book about innovation and breakthrough processes, to be published late 2014. He co- founded an international student conference that continues to this day. He studied in America, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. He holds B.Sc. degrees in philosophy and biochemistry from Brandeis University and an M.Sc. in the philosophy and history of science from the London School of Economics. Mr. Bilski has published on Machiavelli and Plato, and taught seminars on Plato, Machiavelli, Tocqueville, Leo Strauss, Hugo Grotius, and Thucydides at the University of Leiden. With five former Chiefs of Defence, he co-authored the book Towards a Grand Strategy for an Uncertain World (2007) that influenced the new NATO Strategic Concept. Mr. Bilski is a member of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), the Young Atlanticist Working Group of the Atlantic Council, and the Royal Dutch Marksman Association. Elli Fischer Israel Elli Fischer is an independent writer, translator, and rabbi. Previously, he was the JLIC rabbi and campus educator at the University of Maryland. He holds B.A. and M.S. degrees from Yeshiva University and rabbinical ordination from Israel’s Chief Rabbinate. -

Madison Jewish News 4

JEWISH FEDERATION OF MADISON April 2014 Nissan 5774 Inside This Issue Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 Purim in Pictures ............................................16-17 Jewish Education ..........................................22-24 Simchas & Condolences ........................................6 Jewish Social Services....................................20-21 Lechayim Lights ............................................25-27 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............21 Israel & The World ........................................30-31 Community Yom HaShoah Service and Program Sunday, April 27th phy, War, and the Holo- Culture, finalist for the Na- mer Soviet Union and the countries of caust (Rutgers University tional Jewish Book Award, East-Central Europe. It deals with the 6:30 p.m. Press, 2011), finalist for the and New Jews: The End of issues in historical perspective and in the Temple Beth El National Jewish Book the Jewish Diaspora, which context of general, social, economic, 2702 Arbor Drive Award and winner of the has sparked discussion in political, and cultural developments in 2013 Association for Jew- publications like the Econo- the region. The journal includes analyti- Join the Madison Jewish Community ish Studies Jordan mist and the Jerusalem Post. cal, in-depth articles; review articles; Not On for our annual Yom HaShoah service, a Schnitzer Prize, looks at His new project, archival documents; conference notes; Their Last -

The Appeal of Israel: Whiteness, Anti-Semitism, and the Roots of Diaspora Zionism in Canada

THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA by Corey Balsam A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Corey Balsam 2011 THE APPEAL OF ISRAEL: WHITENESS, ANTI-SEMITISM, AND THE ROOTS OF DIASPORA ZIONISM IN CANADA Master of Arts 2011 Corey Balsam Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis explores the appeal of Israel and Zionism for Ashkenazi Jews in Canada. The origins of Diaspora Zionism are examined using a genealogical methodology and analyzed through a bricolage of theoretical lenses including post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and critical race theory. The active maintenance of Zionist hegemony in Canada is also explored through a discourse analysis of several Jewish-Zionist educational programs. The discursive practices of the Jewish National Fund and Taglit Birthright Israel are analyzed in light of some of the factors that have historically attracted Jews to Israel and Zionism. The desire to inhabit an alternative Jewish subject position in line with normative European ideals of whiteness is identified as a significant component of this attraction. It is nevertheless suggested that the appeal of Israel and Zionism is by no means immutable and that Jewish opposition to Zionism is likely to only increase in the coming years. ii Acknowledgements This thesis was not just written over the duration of my master’s degree. It is a product of several years of thinking and conversing with friends, family, and colleagues who have both inspired and challenged me to develop the ideas presented here. -

View Hayley's Resume

AYLEY OLDSTEIN H G RABBINIC LEADERSHIP EXPERIENCE Rabbinic Intern Nehar Shalom | Jamaica Plain, MA September 2018 - Present ○ Lead traditional-egalitarian services and coordinate bi-weekly, songful and joyous “Souly Shabbos” services. ○ Run adult education courses on Chasidut, Talmud, and prayer leading skills. ○ Deliver monthly sermons to congregation. Talmud Educator Shabbat Shelach | Jerusalem, Israel 2017 - 2018 ○ Organized and facilitated a 12-week Beit Midrash for LGBT identified Jewish women in Jerusalem of various religious backgrounds and skill levels. ○ Using the SVARA method, empowered over 20 LGBT Jewish women to learn Talmud in the original in a warm, supportive, and rigorous learning environment. High Holiday Leader Jewish Community of Greater Stowe | Stowe, VT 2014 - 2017 ○ Designed and led High Holiday services with Senior Rabbi, weaving together creative and traditional styles. ○ Wrote and delivered sermons, led the Torah service, and chanted Torah. ○ Designed and led fun and interactive children’s service. ○ Led niggunim singing sessions, yoga sessions, and ‘lunch and learns.’ Hillel Director Boston College | Newton, MA 2016 - 2017 ○ Developed weekly Shabbat and holiday programs with undergraduate students. ○ Mentored students in sermon writing and offered pastoral care. ○ Met with parents of prospective students about Jewish life on campus. YOUTH EDUCATION EXPERIENCE Jewish Educator Temple Beth Zion | Brookline, MA 2015 - 2017 ○ Taught K-3 Hebrew School classes on life cycles, the Jewish calendar, and the weekly Torah portion in a non-denominational setting. Jewish Educator Prozdor | Newton Centre, MA 2014 - 2016 ○ Taught classes such as Embodied Spiritual Practice, Paint the Parsha, and Artist’s Beit Midrash to teenaged students. Community Educator BIMA/Genesis at Brandeis | Waltham, MA Summer 2015 ○ Wrote and taught curriculum on Embodied Jewish Practice for High School Students. -

Is It Cool to Be a Jew? – Significance of Jewishness for Young American Jews at the Beginning of the 21St Century

Is it cool to be a Jew? – Significance of Jewishness for young American Jews at the beginning of the 21st century Olli Saukko Yleisen kirkkohistorian pro gradu -tutkielma Huhtikuu 2017 Ohjaajat Mikko Ketola ja Aila Lauha HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion Laitos Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Kirkkohistorian osasto TekijäFörfattare Saukko, Olli Juhana Työn nimi Arbetets titel Is it cool to be a Jew? – Significance of Jewishness for young American Jews at the beginning of the 21st century Oppiaine Läroämne Yleinen kirkkohistoria Työn laji Arbetets art Aika Datum Sivumäärä Sidoantal Pro gradu -tutkielma 21.4.2017 140 Tiivistelmä Referat Young Jewish adults at the beginning of the 21st century were more integrated into American culture than previous generations. However, they did not hide their Jewishness, but continued to embrace certain aspects of it, and were proud of being Jewish. Due to famous Jews in the entertainment business, Jewish characters in popular television series, and new Jewish counterculture, such as the magazine Heeb, Jewishness in early 21st-century America appeared to be “cooler” than ever. In this study, I examine what kinds of ways of being a Jew and expressing Jewishness there were among young American Jews in the 21st century. How did they see themselves compared with the previous generations, for example concerning their stance towards Israel? I will also examine what attitudes young Jews had towards other American culture, how their Jewishness was seen in everyday life, and what significance their Jewishness had for them. Previous studies have shown that the younger generation of American Jews were more open towards new ways of expressing Jewishness, considered changes in Jewish culture as positive, and created these changes themselves. -

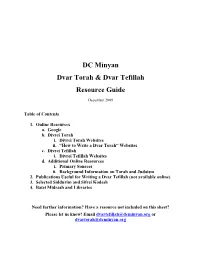

Dvar Torah & Dvar Tefillah Resource Guide

DC Minyan Dvar Torah & Dvar Tefillah Resource Guide December 2009 Table of Contents 1. Online Resources a. Google b. Divrei Torah i. Divrei Torah Websites ii. “How to Write a Dvar Torah” Websites c. Divrei Tefillah i. Divrei Tefillah Websites d. Additional Online Resources i. Primary Sources ii. Background Information on Torah and Judaism 2. Publications Useful for Writing a Dvar Tefillah (not available online) 3. Selected Siddurim and Sifrei Kodesh 4. Batei Midrash and Libraries Need further information? Have a resource not included on this sheet? Please let us know! Email [email protected] or [email protected] Online Resources The Almighty Google (www.google.com) Divrei Torah Dvar Torah sites: (Sites with a weekly Dvar Torah as well as an archive of previous Divrei Torah. They provide great leads for ideas and sources.) Yeshivat Har Etzion: www.vbm-Torah.org/parsha.htm Orthodox Union: www.ou.org/Torah/archive.htm OU parasha summaries: www.ou.org/Torah/tt/aliyaharchive.htm United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism: www.uscj.org/torah_sparks__weekly5467.html Jewish Theological Seminary: www.jtsa.edu/Conservative_Judaism/JTS_Torah_Commentary.xml Bar Ilan University: www.biu.ac.il/JH/Parasha/eng Kolel: The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning: blog.kolel.org Aish HaTorah: www.aish.com/tp American Jewish University: judaism.ajula.edu/Content/InfoUnits.asp?CID=1701 Torah.org www.torah.org/learning/parsha/parsha.html Shamash: shamash.org/tanach/dvar.shtml Torah Online: www.jr.co.il/hotsites/j-Torah.htm Divrei Torah