The Problem of Psychophysical Agency in the Classical Sāmkhya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

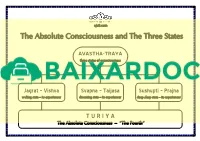

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

What Is Causal Body (Karana Sarira)?

VEDANTA CONCEPTS Sarada Cottage Cedar Rapids July 9, 2017 Peace Chanting (ShAnti PAtha) Sanskrit Transliteration Meaning ॐ गु셁땍यो नमः हरी ओम ्। Om Gurubhyo Namah Hari Om | Salutations to the Guru. सह नाववतु । Saha Nau-Avatu | May God Protect us Both, सह नौ भुन啍तु । Saha Nau Bhunaktu | May God Nourish us Both, सह वीयं करवावहै । Saha Viiryam Karavaavahai| May we Work Together तेजस्वव नावधीतमवतु मा Tejasvi Nau-Adhiitam-Astu Maa with Energy and Vigour, वव饍ववषावहै । Vidvissaavahai | May our Study be ॐ शास््तः शास््तः शास््तः । Om Shaantih Shaantih Enlightening and not give हरी ओम ्॥ Shaantih | Hari Om || rise to Hostility Om, Peace, Peace, Peace. Salutations to the Lord. Our Quest Goal: Eternal Happiness End of All Sufferings Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Fleeting Happiness Endless Suffering Cycle of Birth & Death 3 Vedanta - Introduction Definition: Veda = Knowledge, Anta = End End of Vedas Culmination or Essence of Vedas Leads to God (Truth) Realization Truth: Never changes; beyond Time-Space-Causation Is One Is Beneficial Transforms us Leads from Truth Speaking-> Truth Seeking-> Truth Seeing 4 Vedantic Solution To Our Quest Our Quest: Vedantic Solution: Goal: Cause of Problem: Ignorance (avidyA) of our Real Eternal Happiness Nature End of All Sufferings Attachment (ragah, sangah) to fleeting Objects & Relations Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Remedy: Fleeting Happiness Intense Spiritual Practice (sadhana) Endless Suffering Liberation (mukti/moksha) Cycle of Birth & Death IdentificationIdentification && -

Ahamkara: a Study on the Indian Model of Self and Identity

1 Ahamkara: A study on the Indian model of self and identity Kriti Gupta and Jyotsna Agrawal* Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Patna, Bihar, India *Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health Neurosciences, Bangalore, India Kriti Gupta, (Lead Author), Research Scholar, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Patna, Bihar-800013; email: [email protected], Research interests: Positive Psychology, Indigenous Psychology, Indian Psychology, culture, mental health, psychotherapy. *Dr. Jyotsna Agrawal (Corresponding Author), Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health Neurosciences, Bangalore-56002; email: [email protected], Research interests: Psychotherapy, Positive Psychology, positive emotions, public mental health, child & adolescent mental health, culture, Indigenous Psychology, Indian Psychology, Yoga & Consciousness studies, mind-body medicine, first- person/ subjective research methodologies. Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank Prof. Michael F. Mascolo for his contribution in developing model of mind as per the Indian tradition. We also wish to thank Dr. Smriti Singh for her departmental support. The study was funded under PhD fellowship from IIT Patna, India. 2 Abstract Ideas around self and identity are at the core of various reflective traditions in both East and West. In the psychological literature, they have multiple meanings. However, they usually reflect the idea of self-sameness across changing time. The current study aimed to explore various ways in which contemporary Indians define their ‘self’ and if there were any parallel between modern and traditional construal of self. An open-ended Twenty Statements Test (TST) was used along with a quantitative measure Ahamkara Questionnaire (AQ) based on an Indian model of self, known as ‘ahamkara’. -

VIVEKA CHOODAMANI PART 2 of 9

|| ÌuÉuÉåMücÉÔQûÉqÉÍhÉÈ || VIVEKA CHOODAMANI PART 2 of 9 The Crest Jewel of Discrimination PART 2: SRAVANA – Hearing the Truth “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 11.2 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse -- ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11.2 Viveka Choodamani – Part 2/9 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Isavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge AUTHOR’S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

Talks with Ramana

Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Volume II 23rd August, 1936 Talk 240. D.: The world is materialistic. What is the remedy for it? M.: Materialistic or spiritual, it is according to your outlook. Drishtim jnanamayim kritva, Brahma mayam pasyet jagat Make your outlook right. The Creator knows how to take care of His Creation. D.: What is the best thing to do for ensuring the future? M.: Take care of the present, the future will take care of itself. D.: The future is the result of the present. So, what should I do to make it good? Or should I keep still? M.: Whose is the doubt? Who is it that wants a course of action? Find the doubter. If you hold the doubter the doubts will disappear. Having lost hold of the Self the thoughts afflict you; the world is seen, doubts arise, also anxiety for the future. Hold fast to the Self, these will disappear. D.: How to do it? M.: This question is relevant to matters of non-self, but not to the Self. Do you doubt the existence of your own Self? D.: No. But still, I want to know how the Self could be realised. Is there any method leading to it? M.: Make effort. Just as water is got by boring a well, so also you realise the Self by investigation. D.: Yes. But some find water readily and others with difficulty. M.: But you already see the moisture on the surface. You are hazily aware of the Self. Pursue it. When the effort ceases the Self shines forth. -

The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’S Reception Among the Perennialists

religions Article The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’s Reception Among the Perennialists Mohammad Syifa Amin Widigdo 1,2 1 Faculty of Islamic Studies, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta 55183, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Wonderhome Library, Yogyakarta 55294, Indonesia Received: 14 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 6 May 2020 Abstract: This article studies the reception of the Bhagavad Gita within circles of Perennial Philosophy scholars and examines how the Gita is interpreted to the extent that it influenced their thoughts. Within the Hindu tradition, the Gita is often read from a dualist and/or non-dualist perspective in the context of observing religious teachings and practices. In the hands of Perennial Philosophy scholars, the Gita is read from a different angle. Through a critical examination of the original works of the Perennialists, this article shows that the majority of the Perennial traditionalists read the Gita from a dualist background but that, eventually, they were convinced that the Gita’s paradigm is essentially non-dualist. In turn, this non-dualist paradigm of the Gita influences and transforms their ontological thought, from the dualist to the non-dualist view of the reality. Meanwhile, the non-traditionalist group of Perennial Philosophy scholars are not interested in this ontological discussion. They are more concerned with the question of how the Gita provides certain ways of attaining human liberation and salvation. Interestingly, both traditionalist and non-traditionalist camps are influenced by the Gita, at the same time, inserting an external understanding and interpretation into the Gita. -

Hinduism and Buddhism, Vol I

Hinduism and Buddhism, Vol I. Charles Eliot Hinduism and Buddhism, Vol I. Table of Contents Hinduism and Buddhism, Vol I.........................................................................................................................1 Charles Eliot............................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS. The following are the principal abbreviations used:..............................3 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................3 BOOK II. EARLY INDIAN RELIGION. A GENERAL VIEW.......................................................................47 CHAPTER I. RELIGIONS OP INDIA AND EASTERN ASIA..........................................................47 CHAPTER II. HISTORICAL................................................................................................................52 CHAPTER III. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIAN RELIGION.....................................60 CHAPTER IV. VEDIC DEITIES AND SACRIFICES........................................................................68 CHAPTER V. ASCETICISM AND KNOWLEDGE...........................................................................78 CHAPTER VI. RELIGIOUS LIFE IN PRE−BUDDHIST INDIA.......................................................84 -

GEETHA VAHINI 134, Anantapur District, A.P

Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam P.O. 515 GEETHA VAHINI 134, Anantapur District, A.P. (India.). (The Divine Gospel) All Rights Reserved The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by the Publishers. No part, passage, text or photograph or Artwork of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised, in original language or by translation, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system except with the express and prior permission, in writing from the Convener, Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam (Andhra Pradesh) India - Pin Code 515 134, except for brief passages quoted in book review. This book can be exported from India only by the Publishers by - Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam (India). Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba International Standard Book Number: 81-7208-302-5 First Enlarged Edition: June 2002 Price Rs. PRASANTHI NILAYAM Published by: The Convener, Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam, India - Pin Code 515 134 SRI SATHYA SAI BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS TRUST STD: 08555 ISD: 0091-8555 Grams: BOOKTRUST Prasanthi Nilayam - 515 134 Telephone: 87375 Fax: 87236 Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Grams: BOOK TRUST STD: 08555 ISD: 91-8555 Printed at: Omkar Offset Printers, Phone: 87375 Fax: 87236 No. 3/4, 1 Main, N.T. Pet, Bangalore - 560 002. path of Sathya, asphalted by Dharma and illumined by Prema towards the goal of Shanthi. Arjuna accepted Him in that role, let us do likewise. When worldly attachment hinders the path of duty, when ambition blinds the eyes of sympathy, when hate shuts out the call of Love, let us listen to the Geetha. -

Unifying Knowledge of Praksti in Yoga: Samadhj-With-Seed

UNIFYING KNOWLEDGE OF PRAKSTI IN YOGA: SAMADHJ-WITH-SEED Ian WHICHER 1. Introduction to 'samadhi-with-seed' Patafijali distinguishes between two kinds of samadhi: the first covering all those ecstatic states connected with objects of cognition; and the latter being devoid of objects and thus transcending all mental content. The former, which can also be designated as the "seeded"/"with-seed" (sabrja)l or "extrovertive" type of samadhi, is termed samprajfiata-samadhi 2 and constitutes a range of ecstatic experiences that have an objective "prop" (alambana) with which the mind becomes identified and "united" and which are associated with yogic insight (prajfia). The second kind, what can be called the "objectless" or "introvertive" type of samadhi, is termed asampra jfiata, 3 the "acognitive"4 or rather trans-cognitive enstasy resulting in "seedless" (nirbrja) samadhi. It is acognitive in that there is no longer any cognition of authentic identity (puru$a) as existing in prakrti, no longer misidentification of puru$a with prakrti. As 1 See YS 1.46. As can be easily inferred from YS III.8 saY[lprajfUlta is, compared to the "seedless" (nirbzja) samadhi, an outer limb of Yoga. The Sanskrit text of the YS, the YB of Vyasa, the Tattva-Vaisaradr of Vacaspati Misra and the Raja-Martart4a of Bhoja Raja is from The Yoga-Satras of Patafijali in Agase [1904]. 2 Vyasa (YB 1.1-2 and I.l7) and the main commentators after him understand YS I.17 to refer to samadhi which is linked with objects or mental content; or, as Feuerstein [1979a: 37] puts it, saY[lprajfiata is "object-oriented." YS 1.18 is interpreted by Vyasa as providing information on another kind of samadhi which he calls asaY[lprajfiata and is devoid of all objective supports.