Ahamkara: a Study on the Indian Model of Self and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

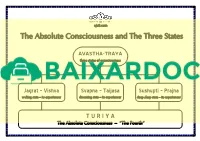

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

Integral Yoga.Pages

ABOUT INTEGRAL YOGA HERSHAYOGA.COM The Goal of Integral Yoga The goal of Integral Yoga and the birthright of every individual is to realise the spiritual unity behind all the diversities of the entire creation and to live harmoniously as members of one universal family. This goal is achieved by developing: a body of optimum health and strength senses under total control a mind well-disciplined, clear and calm an intellect as sharp as a razor a will as strong and pliable as steel a heart full of unconditional love and compassion an ego as pure as crystal and a life filled with Supreme Peace and Joy Integral yoga is a combination of specific methods designed to develop every aspect of the individual: physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual. It is a scientific system, which integrates the various branches of Yoga in order to bring about a complete and harmonious development of the individual. Hatha Yoga: Bodily postures (asanas), deep relaxation, breath control (Pranayama), cleansing processes (kriyas), and mental concentration create a supple and relaxed body; increased vitality; and radiant health. As the body and mind become purified and the practitioner gains mastery over his or her mind, he or she finally attains the goal of Yoga, Self-Realisation. Karma Yoga: The path of action through selfless service. By performing duty without attachment or desire for the results of action, the Karma Yogi purifies his or her mind. When the mind and heart are purified, the Karma Yogi becomes an instrument through which the Divine Plan or Work is performed. Thereby he or she transcends his or her individuality and experiences the Divine Consciousness. -

The Rise of Bengali Yoga (Excerpt from Sun, Moon and Earth: the Sacred Relationship of Yoga and Ayurveda)

The Rise of Bengali Yoga (Excerpt from Sun, Moon and Earth: The Sacred Relationship of Yoga and Ayurveda) By Mas Vidal To set the stage for a moment, the state of Bengal is an eastern state of India and is one of the most densely populated regions on the planet. It is home to the Ganges river delta at the confluence of the Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers. Rivers have always been a sacred part of yoga and the Indian lifestyle. The capital of Bengal is Kolkata, which was the center of the Indian independence movement. As yoga began to expand at the turn of the century through the 1950s, as a counter-cultural force opposed to British occupation, the region also struggled against a tremendous set-back, the Great Bengal Famine of 1943- 44, which took an estimated two to three million lives. India battled through this and eventually gained independence in 1947. Bengal managed to become a womb for bhakti yogis and the nectar that would sustain the renaissance of yoga in India and across the globe. Bengali seers like Sri Aurobindo promoted yoga as an integral system, a way of life that cultivated a dynamic relationship between mind, body, and soul. Some of the many styles of yoga that provide this pure synthesis remain extant in India, but only through a few living yoga teachers and lineages. This synthesis may even still exist sporadically in commercial yoga. One of the most influential figures of yoga in the West was Paramahansa Yogananda, who formulated a practical means of integrating ancient themes and techniques for the spiritual growth of people in Western societies, and for Eastern cultures to reestablish their balance between spirituality and the material. -

What Is Causal Body (Karana Sarira)?

VEDANTA CONCEPTS Sarada Cottage Cedar Rapids July 9, 2017 Peace Chanting (ShAnti PAtha) Sanskrit Transliteration Meaning ॐ गु셁땍यो नमः हरी ओम ्। Om Gurubhyo Namah Hari Om | Salutations to the Guru. सह नाववतु । Saha Nau-Avatu | May God Protect us Both, सह नौ भुन啍तु । Saha Nau Bhunaktu | May God Nourish us Both, सह वीयं करवावहै । Saha Viiryam Karavaavahai| May we Work Together तेजस्वव नावधीतमवतु मा Tejasvi Nau-Adhiitam-Astu Maa with Energy and Vigour, वव饍ववषावहै । Vidvissaavahai | May our Study be ॐ शास््तः शास््तः शास््तः । Om Shaantih Shaantih Enlightening and not give हरी ओम ्॥ Shaantih | Hari Om || rise to Hostility Om, Peace, Peace, Peace. Salutations to the Lord. Our Quest Goal: Eternal Happiness End of All Sufferings Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Fleeting Happiness Endless Suffering Cycle of Birth & Death 3 Vedanta - Introduction Definition: Veda = Knowledge, Anta = End End of Vedas Culmination or Essence of Vedas Leads to God (Truth) Realization Truth: Never changes; beyond Time-Space-Causation Is One Is Beneficial Transforms us Leads from Truth Speaking-> Truth Seeking-> Truth Seeing 4 Vedantic Solution To Our Quest Our Quest: Vedantic Solution: Goal: Cause of Problem: Ignorance (avidyA) of our Real Eternal Happiness Nature End of All Sufferings Attachment (ragah, sangah) to fleeting Objects & Relations Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Remedy: Fleeting Happiness Intense Spiritual Practice (sadhana) Endless Suffering Liberation (mukti/moksha) Cycle of Birth & Death IdentificationIdentification && -

Integral Yoga Basic Teacher Training 2019 Working Doc.Pub

Integral Yoga® 200-hour Hatha I Teacher Training Australian Program 2018/2019 Dates to be announced ® An internationally recognised Yoga Teacher Training program, where you have the opportunity to live Yoga as fully as possible, learning to teach with confidence, from the depth of your own experience. Dear friend, Hari Om! Thank you for your interest in the Integral Yoga 200-hour Teacher Training Program. It is wonderful that you are considering expanding your experiences of Yoga through Teacher Training. For over forty years students from all around the world have participated in Integral Yoga Teacher Trainings and we are delighted once again to be able to offer Integral Yoga Teacher Training in Australia. This comprehensive certification program provides a strong foundation for personal and spiritual develop- ment, an appreciation for nurturing your own practice, and skills to become a knowledgeable and professional Yoga Teacher. The Integral Yoga training process naturally fosters the sensitivities to help you create a safe environment where your students will feel free to realize their own potential, gaining respect for themselves and a greater capacity to be of service to others. The program runs over 12 months and offers a 200 hour certification. We really want the training to be as accessible as possible, so session dates will be negotiated to best suit participants. The training includes residential retreats and non-residential training days as well as home practice, attendance at Integral Yoga Hatha classes and completion of written and practical assessment tasks. The combination of residential and extended part-time training offers the ideal opportunity to experience the teachings of Integral Yoga in depth and integrate them into your daily life. -

Sivananda's Integral Yoga

SIVANANDA'S INTEGRAL YOGA By Siva-Pada-Renu SWAMI VENKATESANANDA 6(59(/29(*,9( 385,)<0(',7$7( 5($/,=( So Says Sri Swami Sivananda Sri Swami Venkatesananda A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION Seventh Edition: 1981 (2000 Copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition : 1998 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. PRAYERFUL DEDICATION TO BHAGAVAN SIVANANDA Lord! Condescend to accept this humble flower, fragrant with the aroma of thine own divine glory, immeasurable and infinite. Hundreds of savants and scholars might write hundreds of tomes on your glory, yet it would still transcend them all. In accordance with thine ancient promise: yada yada hi dharmasya glanir bhavati bharata abhyutthanamadharmasya tadatmanam srijamyaham paritranaya sadhoonam vinasaya cha dushkritam dharmasamsthapanarthaya sambhavami yuge yuge (Gita IV–7, 8) You, the Supreme Being, the all-pervading Sat-chidaranda-Para-Brahman, have taken this human garb and come into this world to re-establish Dharma (righteousness). The wonderful transformation you have brought about in the lives of millions all over the world is positive proof of your Divinity. I am honestly amazed at my own audacity in trying to bring this Supreme God, Bhagavan Sivananda, to the level of a human being (though Sage Valmiki had done so while narrating the story to Lord Rama) and to describe the Yoga of the Yogeshwareshwara, the goal of all Yogins. Lord! I cling to Thy lotus-feet and beg for Thy merciful pardon. -

Understanding Integral Yoga of Sri Aurobindo © 2018 IJPNPE Received: 25-11-2017 Sunil Kumar Accepted: 26-12-2017

International Journal of Physiology, Nutrition and Physical Education 2018; 3(1): 1606-1608 ISSN: 2456-0057 IJPNPE 2018; 3(1): 1606-1608 Understanding integral yoga of Sri Aurobindo © 2018 IJPNPE www.journalofsports.com Received: 25-11-2017 Sunil Kumar Accepted: 26-12-2017 Sunil Kumar Abstract MA NET in Yoga, Head The goal of yoga is to become free of the cycle of birth and death and attain union with God. The soul Constable Delhi Police India that is afflicted with birth, death, sorrow, falsehood, disease and ignorance wants to escape from them. Sri Aurobindo who was an Indian Yogi, Philosopher, Guru, gave the concept of a new form of yogic philosophy being not satisfied with the approaches of traditional yogic philosophies. He called his yoga ‘Purna Yoga’ or ‘Integral Yoga’. This yoga aims at the conscious union with the Divine in the supermind and the transformation of the nature. It is a collective yoga that transforms life universally. This paper is and attempt to study and understand the philosophy and approach of the Integral Yoga and try to understand the differences of Integral yoga with the traditional yoga approaches. Keywords: Integral yoga, Indian yogi, Purna yoga, yoga approaches Introduction Sri Aurobindo developed a new method of yoga which subsequently became known as Integral Yoga because he felt that all other branches of yoga were not adequate for the realisation of the totality of the truth. Sri Aurobindo’s concept of the integral yoga is very comprehensive. He had a clear system of practice that he called integral yoga, as it was based on a synthesis of different paths of yoga. -

Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 6 9-1-2018 Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Banerji, D. (2018). Sri Aurobindo's formulations of the integral yoga. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 37 (1). http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2018.37.1.38 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950) developed, practiced and taught a form of yoga, which he named integral yoga. If one peruses the texts he has written pertaining to his teaching, one finds a variety of models, goals, and practices which may be termed formulations or versions of the integral yoga. This article compares three such formulations, aiming to determine whether these are the same, but in different words, as meant for different audiences, or whether they represent different understandings of the yoga based on changing perceptions. -

The Problem of Psychophysical Agency in the Classical Sāmkhya

ArgUmEnt Vol. 5 (1/2015) pp. 25–34 e‑ISSn 2084–1043 ISS n 2083–6635 The problem of psychophysical agency in the classical Sāmkhya. and Yoga * marzenna JAKUBCZAK ABStrACt the paper discusses the issue of psychophysical agency in the context of Indian philosophy, focusing on the oldest preserved texts of the classical tradition of SāṃkhyaYoga. the author raises three major questions: What is action in terms of Sāṃkhyakārikā (ca. fifth century CE) and Yogasūtra (ca. third century CE)? Whose action is it, or what makes one an agent? What is a right and morally good action? the first part of the paper reconsiders a general idea of action — including actions that are deliberately done and those that ‘merely’ happen — identified by Patañjali and Ῑśvarakṛṣṇa as a permanent change or transformation (pariṇāma) determined by the universal principle of causation (satkārya). then, a threefold categorization of actions according to their causes is presented, i.e. internal agency (ādhyātmika), external agency (ādhi bhautika) and ‘divine’ agency (ādhidaivika). the second part of the paper undertakes the prob lem of the agent’s autonomy and the doer’s psychophysical integrity. the main issues that are exposed in this context include the relationship between an agent and the agent’s capacity for perception and cognition, as well as the crucial SāṃkhyaYoga distinction between ‘a doer’ and ‘the self ’. the agent’s selfawareness and his or her moral selfesteem are also briefly examined. moreover, the efficiency of action in present and future is discussed (i.e. karman, karmāśaya, saṃskāra, vāsanā), along with the criteria of a right act accomplished through meditative in sight (samādhi) and moral discipline (yama).