Unifying Knowledge of Praksti in Yoga: Samadhj-With-Seed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

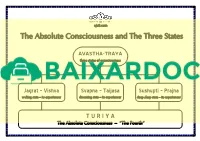

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Honors Theses Department of Religious Studies 9-11-2006 Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara Brandie Martinez-Bedard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_hontheses Recommended Citation Martinez-Bedard, Brandie, "Types of Causes in Aristotle and Sankara." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_hontheses/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYPES OF CAUSES IN ARISTOTLE AND SANKARA by BRANDIE MARTINEZ BEDARD Under the Direction of Kathryn McClymond and Sandra Dwyer ABSTRACT This paper is a comparative project between a philosopher from the Western tradition, Aristotle, and a philosopher from the Eastern tradition, Sankara. These two philosophers have often been thought to oppose one another in their thoughts, but I will argue that they are similar in several aspects. I will explore connections between Aristotle and Sankara, primarily in their theories of causation. I will argue that a closer examination of both Aristotelian and Advaita Vedanta philosophy, of which Sankara is considered the most prominent thinker, will yield significant similarities that will give new insights into the thoughts -

Philosophy of Mind: an Advaita Vedanta Perspective

Philosophy of Mind: An Advaita Vedanta Perspective SURYA KANT A MAHARANA Philosophy of mind and the philosophical issues arising in the allied domain of cognitive sciences constitute a fast developing territory in the world of philosophical enquiry. The origin of the philosophy of mind can be traced back to the Greek period. Anaxagoras (of Athens; perhaps in 500-428 BC) taught tha t all things come from the mixing of innumerable tiny particles of all kinds of substance, shaped by a separate, immaterial, creating principle, Nous ('Mind'). Nous is not explicitly called divine, but has the qualities of a creating god; Nous does not create matter, but rather creates the forms that matter assumes. However, in the Western philosophical tradition, one can hardly find a cleavage between mind a nd consciousness. On the contrary, it is quite fascinating to discover th at there is a hard and fast cleavage be tween miJU! and consciousness in the classical Indian philosophical tradition, especiall y in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta. In this direction, the paper is an attempt to discover the unique structure of mind and to distinguish it from consciousness in the light of the champion of Advaita Vedanta, Adi Salikaracarya. To begin wi th, in the Western tradition, the terms 'mind', 'self' and 'consciousness' are often used synonymously. The renowned philosopher, Rene Descartes, makes a sharp and radical division between mind and body. 1 The two are regarded as separate and independent substances and it is thought that the interaction between ~hem is i.mpossible c x~ept t~rough some inexplicable or mysterious mterv~nll on or connectiOn.' Tile facts of the connection between body and mmd are so compelhng that Descartes was obliged to assume the connection between the two through the pineal gland. -

FOUNDATIONS of SATYAGRAHA Dr Madhu Prashar Principal, Dev Samaj College for Women, Ferozepur City, Punjab

© 2014 JETIR August 2014, Volume 1, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) FOUNDATIONS OF SATYAGRAHA Dr Madhu Prashar Principal, Dev Samaj College for Women, Ferozepur City, Punjab. ABSTRACT The Gandhian technique of Satyagraha could be characterised by the term 'syncretic'. Although the impact of the west upon Indian traditions has elicited a response that is truly Indian, the end product bears non-mistakeable traces of the thought and experience of modern Europe. Efforts to revitalize Hinduism by creating a Hindu Raj and recover the glories of an idealized Hindu past were (and continue to be made by social and political groups and orthodox Hindu political parties. The importance of differentiating the Gandhian technique on the one hand, from the purely traditional on the other, cannot be over emphasised. As already mentioned, Gandhi used the traditional to promote the novel, reinterpreting tradition in such a way that revolutionary ideas, clothed in familiar expression, were readily adopted and employed towards revolutionary ends. In this research paper, it will be highlighted that how the two streams of thought merge and how Gandhi's leadership and creativeness transform elements from both developed the Satyagraha technique and can be understood better by analysing aspects of Hindu tradition in his background – the philosophical concept of Satya, the popular and ethical meaning of the Jain, Buddhist and Hindu ideal of Ahimsa, and concept of tapas (self-suffering) in Indian ethics will also be covered. INTRODUCTION: Gandhi has repeatedly acknowledged the influence of Western thinkers like Tolstoy, Ruskin, Thoreau the New Testament. In each case the influence was only of the nature of corroboration of an already accepted ethical precept, and a crystallization of basic predispositions. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

What Is Causal Body (Karana Sarira)?

VEDANTA CONCEPTS Sarada Cottage Cedar Rapids July 9, 2017 Peace Chanting (ShAnti PAtha) Sanskrit Transliteration Meaning ॐ गु셁땍यो नमः हरी ओम ्। Om Gurubhyo Namah Hari Om | Salutations to the Guru. सह नाववतु । Saha Nau-Avatu | May God Protect us Both, सह नौ भुन啍तु । Saha Nau Bhunaktu | May God Nourish us Both, सह वीयं करवावहै । Saha Viiryam Karavaavahai| May we Work Together तेजस्वव नावधीतमवतु मा Tejasvi Nau-Adhiitam-Astu Maa with Energy and Vigour, वव饍ववषावहै । Vidvissaavahai | May our Study be ॐ शास््तः शास््तः शास््तः । Om Shaantih Shaantih Enlightening and not give हरी ओम ्॥ Shaantih | Hari Om || rise to Hostility Om, Peace, Peace, Peace. Salutations to the Lord. Our Quest Goal: Eternal Happiness End of All Sufferings Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Fleeting Happiness Endless Suffering Cycle of Birth & Death 3 Vedanta - Introduction Definition: Veda = Knowledge, Anta = End End of Vedas Culmination or Essence of Vedas Leads to God (Truth) Realization Truth: Never changes; beyond Time-Space-Causation Is One Is Beneficial Transforms us Leads from Truth Speaking-> Truth Seeking-> Truth Seeing 4 Vedantic Solution To Our Quest Our Quest: Vedantic Solution: Goal: Cause of Problem: Ignorance (avidyA) of our Real Eternal Happiness Nature End of All Sufferings Attachment (ragah, sangah) to fleeting Objects & Relations Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Remedy: Fleeting Happiness Intense Spiritual Practice (sadhana) Endless Suffering Liberation (mukti/moksha) Cycle of Birth & Death IdentificationIdentification && -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Creation, Creator and Causality: Perspectives from Purānic Genre of Hindu Literature

IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship Volume 8 – Issue 1 – Winter 2019 Creation, Creator and Causality: Perspectives from Purānic Genre of Hindu Literature Sivaram Sivasubramanian Jain (deemed-to-be-university), India Rajani Jairam Jain (deemed-to-be-university), India 139 IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship Volume 8 – Issue 1 – Winter 2019 Abstract Inspirited by a growing recognition of the need for an interdisciplinary approach in dealing with science and religion, this article aims to decode the nature of the causal relationship between creator and creation as epitomized in a few select scriptures of Purānic genre of Hindu Literature. The present study is part of an overarching effort to understand how ancient Indian knowledge and culture have supported profound metaphysical inquiries amidst flourishing religious practices. The nature of this work requires the utilization of a research protocol that combines the exploratory interpretation of scriptures and an explanation of causality. Notably, there is a consensus among the Purānas on the fundamental tenet that a primal creator is the eternal cause of the cycle of creation, sustenance, dissolution, and re-creation. Working from this premise, Purānas depict the primal creator as imperceptible, enigmatic, and absolute; hence, a thorough understanding is impossible. With this underlying principle, Purānas provide a metaphysical basis for the Hindu Trinity (Brahma, Vishnu, Rudra), the quintessence of Hindu Theology. This research paper concludes that the Purānas chosen for this study (a) point to a relational causality of creation of this universe that manifests from the unmanifest creator, and (b) proffer an intriguing description of how equilibrium-disequilibrium among gunas influence the cycle of cause-effect. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm.