The Patient Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION and WHY

DRAFT EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES (June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT? Medical record documentation is required to record pertinent facts, findings, and observations about an individual's health history including past and present illnesses, examinations, tests, treatments, and outcomes. The medical record chronologically documents the care of the patient and is an important element contributing to high quality care. The medical record facilitates: · the ability of the physician and other health care professionals to evaluate and plan the patient's immediate treatment, and to monitor his/her health care over time. · communication and continuity of care among physicians and other health care professionals involved in the patient's care; · accurate and timely claims review and payment; · appropriate utilization review and quality of care evaluations; and · collection of data that may be useful for research and education. An appropriately documented medical record can reduce many of the "hassles" associated with claims processing and may serve as a legal document to verify the care provided, if necessary. WHAT DO PAYERS WANT AND WHY? Because payers have a contractual obligation to enrollees, they may require reasonable documentation that services are consistent with the insurance coverage provided. They may request information to validate: · the site of service; · the medical necessity and appropriateness of the diagnostic and/or therapeutic services provided; and/or · that services provided have been accurately reported. II. GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MEDICAL RECORD DOCUMENTATION The principles of documentation listed below are applicable to all types of medical and surgical Pg. 1 services in all settings. For Evaluation and Management (E/M) services, the nature and amount of physician work and documentation varies by type of service, place of service and the patient's status. -

Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS-D Guidance Manual Effective January 1, 2019

Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS-D Guidance Manual Effective January 1, 2019 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services PRA Disclosure Statement According to the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, no persons are required to respond to a collection of information unless it displays a valid OMB control number. The valid OMB control number for this information collection is x. The time required to complete this information collection is estimated to average 0.3 minutes per response, including the time to review instructions, search existing data resources, gather the data needed, and complete and review the information collection. This estimate does not include time for training. If you have comments concerning the accuracy of the time estimate(s) or suggestions for improving this form, please write to: CMS, 7500 Security Boulevard, Attn: PRA Reports Clearance Officer, Mail Stop C4-26-05, Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850. *****CMS Disclaimer*****Please do not send applications, claims, payments, medical records or any documents containing sensitive information to the PRA Reports Clearance Office. Please note that any correspondence not pertaining to the information collection burden approved under the associated OMB control number listed on this form will not be reviewed, forwarded, or retained. If you have questions or concerns regarding where to submit your documents, please contact Joan Proctor National Coordinator, Home Health Quality Reporting Program Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. OASIS-D Guidance Manual Table of Contents Page -

The Oral Presentation Nersi Nikakhtar, M.D

Guidelines for the Oral Presentation Nersi Nikakhtar, M.D. University of Minnesota Medical School !1 Table of Contents The Oral Presentation: An Introduction ..................................3 Why Worry About the Oral Presentation? ...............................4 Presenting the New Patient .....................................................5 The Opening Statement ......................................................5 History of Present Illness ....................................................5 Past Medical History ...........................................................6 Medications/Allergies ..........................................................7 Social and Family History ...................................................7 Review of Systems ..............................................................7 Vitals .....................................................................................8 Physical Exam .....................................................................8 Labs and Studies .................................................................8 Summary Statement ............................................................8 Assessment and Plan ..........................................................9 The Follow Up (or Daily) Presentation: What's Different? ...................................................................11 The Outpatient (Known Patient) Presentation: What's Different? ...................................................................12 !2 The Oral Presentation: An Introduction The -

Neurology History and Physical Guidelines

Neurology History and Physical Guidelines HISTORY Chief Complaint — A maximally succinct statement of the patient: - Age, handedness, gender - Problem and its duration - May include major relevant risk factors (if any), e.g. hypertension, coronary artery disease in a stroke patient. - Rarely need to mention imaging if that was reason for the consult (not in every case) - May specify who the historian was and quality of informant’s history if different from usual - E.g: 56 year old right-handed woman that presents with three days of garbled speech and right sided weakness with a history significant for high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus History of Present Illness — - Briefly include usual state of health (baseline): e.g: “normal, active, fully functional”; “residual mild right hemiparesis and can ambulate 50 feet with walker”; “at baseline, oriented to self, transfers by lift, and cannot recognize family members”, etc. - Concisely and chronologically describe symptoms which prompted medical attentions (Timeline) - For each try to include as many details: location, quality/severity, chronology (when it first began, mode of onset, mode of ending, duration, frequency), setting, aggravating and alleviating factors, treatment, associated symptoms, overall course, effect on normal activities, previous history of similar symptoms - Include pertinent negative symptoms that relate to differential diagnosis and localization - Pertinent past medical history and family history - Put present symptoms in context of pre-existing chronic illness. If the chronic illness is neurological, how it was diagnosed/confirmed - Hospital course: most relevant information (vital signs, early exam, treatments, response to therapy, symptom evolution) - Only include information that contributes in an important way to diagnosis or management. -

The AOA Guide

The AOA Guide: How to Succeed in the Third-Year Clerkships Example Notes for the MSIII 2017 Preface This guide was created as a way of assisting you as you start your clinical training. For the rest of your professional life, you will write various notes. Although they will eventually become second nature to you, it is often challenging at first to figure out what information is pertinent to a particular specialty/rotation.This book is designed to help you through that process. In this book you will find samples of SOAP notes for each specialty and a complete History and Physical. Each of these notes represents very typical patients you will see on the rotation. Look at the way the notes are phrased and the information they contain. We have included an abbre- viations page at the end of this book so that you can refer to it for the short-forms with which you are not yet familiar. Pretty soon you will be using these abbrevia- tions without a problem! These notes can be used as a template from which you can adjust the information to apply to your patient. It is important to remember that these notes are not all inclusive, of course, and other physicians will give sugges- tions that you should heed. If you are ever having trouble, us fourth year medical students are always willing to help! ***NOTE: Many note-writing practices at Jefferson may change as the hospital transitions from paper notes to EMR.*** Table of Contents Internal Medicine Progress Note (SOAP) ............................................................3 Neurology Progress Note (SOAP) ...................................................................... -

Assessment of an Adult Living with HIV

The fundamentals of the clinical assessment of an adult living with HIV Note: Pictures have been removed from the slides for copyright purposes Talitha Crowley (Stellenbosch University) Helen Woolgar (Stellenbosch University) Stacie Stender (Jhpiego) 2 Overview 1. Reasons for performing a clinical assessment 2. Approach to a clinical assessment 3. Subjective history taking 4. Objective examination 5. Assessment and plan 6. Summary 1. Discuss why a clinical assessment should be performed on a HIV infected patient. 2. Recognise possible abnormal findings from a subjective history as well as a physical examination. 3. Make an accurate patient assessment and develop an appropriate care plan. 4 Reasons for performing an assessment A study in Pretoria about • Establish baseline data about the the quality of services in ART clinics found that a patient’s health when diagnosed physical assessment was with HIV and before starting ART. performed in only 41.1% of patients (Kinkel et al. 2012) • Identify opportunistic infections that needs treatment. • Identify any other chronic conditions that may develop while a patient is on ART. 5 Approach to a clinical assessment • Subjective - history taking • Objective - physical examination • Assessment of subjective and objective findings and differential diagnosis • Plan 6 Comprehensive assessment • Subjective: History Taking e.g. previous illness, symptoms • Objective: General assessment, JACCOL, basic data, systems examination, diagnostic tests / investigations • Assessment: Diagnosis & WHO stage • Plan: -

American Geriatrics Society ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS for GERIATRICS HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

American Geriatrics Society ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS FOR GERIATRICS HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS General Components of an EHR 1. Data should be in structured format for easy retrievability and monitoring over time. 2. 24 hour IT support should be available. 3. Automatic billing level suggestion (and submission of bill). 4. Retrievability of data for quality reporting and research. 5. Previous button to import last visits data into various (all or some) fields. 6. Reminders for preventive care that is due. 7. Options for users to add test, scales, etc. as knowledge and evidence develop and warrant it. 8. Designated area for caregiver information. Specific Geriatric Components of an EHR History o Cognitive Screening (Montreal Cognitive o Facility Information Assessment {MoCA}, Saint Louis University Mental o Risk Factors: falls, depression screening with link to tool, Status {SLUMs}, etc.) sexually transmitted disease risk, alcohol, drugs, nutrition, o Depression Screening (Geriatric depression scale, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, functional decline, Patient Health Questionnaire {PHQ‐9, etc}) pressure sores, etc. o Pain level and location(s) o Advanced Directives, Healthcare Power of Attorney (HCPOA) o Medication list: o Activities of Daily Living (ADLs): bathing, dressing, grooming, o sort by alphabet, entry date, deleted, category/ continence, walking, transfer, eating, etc. disease, and o Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs): finances, o include over the counter medications, oxygen, driving, telephone, medication, etc. walker, hospital bed, physical therapy, etc. o Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Speech Therapy o Problem list: sort by alphabet, entry date, category o Durable Medical Equipment o History of Present Illness (HPI) ‐ import previous o Oxygen o Home Health Agency o Review of Systems (ROS), include: ROS could not be o Home Assessment: stairs, railings, heating, air, obtained due to patient’s condition (replace condition with flooring, bathroom, smoke detector. -

The Examination Process Matthew R

CHAPTER 2 © sbayram/E+/Getty Images The Examination Process Matthew R. Kutz, PhD, ATC, CSCS OVERVIEW LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter focuses on the injury evaluation pro- After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to cess and how a proper evaluation contributes to do the following: the clinical diagnosis and patient’s plan of care. 1. Describe the injury evaluation process. Many nuances to the injury evaluation process 2. Understand the necessity of a systematic and contribute to the identification and classification organized approach to injury evaluation. of an injury. These nuances also affect which body 3. Articulate key questions to ask when taking a parts are evaluated relative to the primary injury, history. the treatment options, and the overall plan of care. 4. Understand the importance and necessity of It is impossible to identify and discuss every pos- inspections, palpitations, and special tests. sible nuance during an evaluation in a text such 5. Understand the difference between the HIPS injury as this. Therefore, the skilled clinician is required assessment and the SOAP note-taking format. to integrate and assess a very complex “web” of 6. Understand the difference between primary and information supplied by the patient, the clinician’s secondary evaluations. observation of the injury (if he or she was there), the patient’s presentation, the clinician’s experienc e, valid and reliable research evidence, and the FUN FACTS ABOUT INJURY experience and input from reliable stakeholders (eg, other health care providers and observations EVALUATION from witnesses). Sometimes, the information • Although all injury evaluations should be structured gathered from all of these different sources may and organized, they do not necessarily have to follow be contradictory, and so it must be carefully and a prescribed sequence. -

Foundations of Physical Examination and History Taking

UNIT I Foundations of Physical Examination and History Taking CHAPTER 1 Overview of Physical Examination and History Taking CHAPTER 2 Interviewing and The Health History CHAPTER 3 Clinical Reasoning, Assessment, and Plan CHAPTER Overview of 1 Physical Examination and History Taking The techniques of physical examination and history taking that you are about to learn embody time-honored skills of healing and patient care. Your ability to gather a sensitive and nuanced history and to perform a thorough and accurate examination deepens your relationships with patients, focuses your assessment, and sets the direction of your clinical thinking. The qual- ity of your history and physical examination governs your next steps with the patient and guides your choices from among the initially bewildering array of secondary testing and technology. Over the course of becoming an ac- complished clinician, you will polish these important relational and clinical skills for a lifetime. As you enter the realm of patient assessment, you begin integrating the es- sential elements of clinical care: empathic listening; the ability to interview patients of all ages, moods, and backgrounds; the techniques for examining the different body systems; and, finally, the process of clinical reasoning. Your experience with history taking and physical examination will grow and ex- pand, and will trigger the steps of clinical reasoning from the first moments of the patient encounter: identifying problem symptoms and abnormal find- ings; linking findings to an underlying process of pathophysiology or psycho- pathology; and establishing and testing a set of explanatory hypotheses. Working through these steps will reveal the multifaceted profile of the patient before you. -

"Survival Guide" to the Clinics

Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania SURVIVAL GUIDE TO THE CLINICS 2018 •♦ Introduction ♦• The transition from the basic sciences to the clinics is naturally intimidating. You’ll soon be immersed in an unfamiliar environment that will demand greater responsibility and commitment than anything you’ve previously encountered in medical school. But fear not! Working with patients is (hopefully) what you went to med school for in the first place. Though your white coat may feel awkward, you are more than ready to begin navigating the corridors of HUP. While your clerkship year will occasionally be anxiety provoking and exhausting, it will more often be exhilarating, exciting, and fun. You’ll interact daily and influentially with patients, become a valuable member of medical and surgical teams, see the practical application of the things you’ve learned, and finally sense yourself becoming a true clinician (it feels like a slight tingle). This guide is intended to help ease your transition into the clinics. Each rotation and each site has its own distinct flavor. What is expected of you as a student will vary from one rotation to the next and from team to team. Rather than attempt to describe every detail of each rotation, this Survival Guide presents general objectives, opportunities, and responsibilities, as well as some helpful advice from previous students. Above all, your fellow classmates and upperclassmen will be a tremendous resource throughout this core clinical year. Enthusiasm, dedication, and flexibility are the keys to performing well and learning in the clinics. Throughout your clinical experience, you’ll interact with an incredibly diverse group of attendings, residents, and students in a variety of medical environments. -

Assessment and Management of Patients with Hypertension

Chapter 32 G Assessment and Management of Patients With Hypertension LEARNING OBJECTIVES G On completion of this chapter, the learner will be able to: 1. Define blood pressure and identify risk factors for hypertension. 2. Explain the difference between normal blood pressure and hyper- tension and discuss the significance of hypertension. 3. Describe the treatment approach for hypertension, including lifestyle changes and medication therapy. 4. Use the nursing process as a framework for care of the patient with hypertension. 5. Describe the necessity for immediate treatment of hypertensive crisis. 854 Chapter 32 Assessment and Management of Patients With Hypertension 855 B lood pressure is the product of cardiac output multiplied by Primary Hypertension peripheral resistance. Cardiac output is the product of the heart rate multiplied by the stroke volume. In normal circulation, pres- Between 21% and 36% of the adult population in the United States sure is exerted by the flow of blood through the heart and blood has hypertension (Hajjar & Kotchen, 2003). Of this population, be- vessels. High blood pressure, known as hypertension, can result tween 90% and 95% have primary hypertension, meaning that from a change in cardiac output, a change in peripheral resis- the reason for the elevation in blood pressure cannot be identified. tance, or both. The medications used for treating hypertension The remaining 5% to 10% of this group have high blood pressure decrease peripheral resistance, blood volume, or the strength and related to specific causes, such as narrowing of the renal arteries, rate of myocardial contraction. renal parenchymal disease, hyperaldosteronism (mineralocorticoid hypertension) certain medications, pregnancy, and coarctation of the aorta (Kaplan, 2001). -

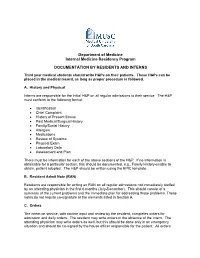

Documentation by Residents and Interns 2020

Department of Medicine Internal Medicine Residency Program DOCUMENTATION BY RESIDENTS AND INTERNS Third year medical students should write H&Ps on their patients. These H&Ps can be placed in the medical record, as long as proper procedure is followed. A. History and Physical Interns are responsible for the initial H&P on all regular admissions to their service. The H&P must conform to the following format: • Identification • Chief Complaint • History of Present Illness • Past Medical/Surgical History • Family/Social History • Allergies • Medications • Review of Systems • Physical Exam • Laboratory Data • Assessment and Plan There must be information for each of the above sections of the H&P. If no information is obtainable for a particular section, this should be documented, e.g., Family History-unable to obtain, patient adopted. The H&P should be written using the EPIC template. B. Resident Admit Note (RAN) Residents are responsible for writing an RAN on all regular admissions not immediately staffed by an attending physician in the first 6 months (July-December). This should consist of a summary of the current problems and the immediate plan for addressing those problems. These notes do not require co-signature or the elements listed in Section A. C. Orders The intern on service, with routine input and review by the resident, completes orders for admission and daily orders. The resident may write orders in the absence of the intern. The attending physician may write orders as well, but this should be done only in an emergency situation and should be co-signed by the house officer responsible for the patient.