Surgical Documentation Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stethoscope: Some Preliminary Investigations

695 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The stethoscope: some preliminary investigations P D Welsby, G Parry, D Smith Postgrad Med J: first published as on 5 January 2004. Downloaded from ............................................................................................................................... See end of article for Postgrad Med J 2003;79:695–698 authors’ affiliations ....................... Correspondence to: Dr Philip D Welsby, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK; [email protected] Submitted 21 April 2003 Textbooks, clinicians, and medical teachers differ as to whether the stethoscope bell or diaphragm should Accepted 30 June 2003 be used for auscultating respiratory sounds at the chest wall. Logic and our results suggest that stethoscope ....................... diaphragms are more appropriate. HISTORICAL ASPECTS note is increased as the amplitude of the sound rises, Hippocrates advised ‘‘immediate auscultation’’ (the applica- resulting in masking of higher frequency components by tion of the ear to the patient’s chest) to hear ‘‘transmitted lower frequencies—‘‘turning up the volume accentuates the sounds from within’’. However, in 1816 a French doctor, base’’ as anyone with teenage children will have noted. Rene´The´ophile Hyacinth Laennec invented the stethoscope,1 Breath sounds are generated by turbulent air flow in the which thereafter became the identity symbol of the physician. trachea and proximal bronchi. Airflow in the small airways Laennec apparently had observed two children sending and alveoli is of lower velocity and laminar in type and is 6 signals to each other by scraping one end of a long piece of therefore silent. What is heard at the chest wall depends on solid wood with a pin, and listening with an ear pressed to the conductive and filtering effect of lung tissue and the the other end.2 Later, in 1816, Laennec was called to a young characteristics of the chest wall. -

Myocardial Hamartoma As a Cause of VF Cardiac Arrest in an Infant a Frampton, L Gray, S Bell

590 CASE REPORTS Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.009951 on 26 July 2005. Downloaded from Myocardial hamartoma as a cause of VF cardiac arrest in an infant A Frampton, L Gray, S Bell ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2005;22:590–591. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.009951 ardiac arrests in children are fortunately rare and the patients. However a review by Young et al2 found that the presenting cardiac rhythm is often asystole. However, survival to hospital discharge in infants and children Cventricular fibrillation (VF) can occur and may respond presenting with VF/VT was of the order of 30%, compared favourably to defibrillation. with only 5% of patients whose initial presenting rhythm was asystole. VF has also been demonstrated to be relatively more CASE REPORT common in infants than any other paediatric age group A 7 month old girl was sitting in her high chair when she was (p,0.006).1 One study of over 500 000 children presenting to witnessed by her parents to collapse suddenly at 1707 hours. an ED over a period of 5 years found VF to be the third most They attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the common presenting cardiac arrhythmia of any origin in ambulance crew arrived 7 minutes later, the cardiac monitor infants below the age of 1 year.1 It has been suggested that a displaying VF. No defibrillation or medications were admi- subgroup of patients (those ,1 year old) that would benefit nistered and she was rapidly transferred to her nearest from early defibrillation can be identified.2 emergency department (ED), arriving at 1723. -

Automated Classification of Medical Percussion Signals for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Injuries Bhuiyan Md Moinuddin Universty of Windsor

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013 Automated Classification of Medical Percussion Signals for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Injuries Bhuiyan Md Moinuddin Universty of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Md Moinuddin, Bhuiyan, "Automated Classification of Medical Percussion Signals for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Injuries" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 4941. This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Automated Classification of Medical Percussion Signals for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Injuries By Md Moinuddin Bhuiyan A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2013 © 2013, Md Moinuddin Bhuiyan All Rights Reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored or otherwise retained in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, on any medium by any means without prior written permission of the author. -

Bates' Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

Lynn S. Bickley, MD, FACP Clinical Professor of Internal Medicine School of Medicine University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Peter G. Szilagyi, MD, MPH Professor of Pediatrics Chief, Division of General Pediatrics University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York Acquisitions Editor: Elizabeth Nieginski/Susan Rhyner Product Manager: Annette Ferran Editorial Assistant: Ashley Fischer Design Coordinator: Joan Wendt Art Director, Illustration: Brett MacNaughton Manufacturing Coordinator: Karin Duffield Indexer: Angie Allen Prepress Vendor: Aptara, Inc. 7th Edition Copyright © 2013 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2009 by Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2007, 2004, 2000 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 1995, 1991 by J. B. Lippincott Company. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appear- ing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at Two Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia PA 19103, via email at [email protected] or via website at lww.com (products and services). 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bickley, Lynn S. Bates’ pocket guide to physical examination and history taking / Lynn S. -

(June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION and WHY

DRAFT EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES (June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT? Medical record documentation is required to record pertinent facts, findings, and observations about an individual's health history including past and present illnesses, examinations, tests, treatments, and outcomes. The medical record chronologically documents the care of the patient and is an important element contributing to high quality care. The medical record facilitates: · the ability of the physician and other health care professionals to evaluate and plan the patient's immediate treatment, and to monitor his/her health care over time. · communication and continuity of care among physicians and other health care professionals involved in the patient's care; · accurate and timely claims review and payment; · appropriate utilization review and quality of care evaluations; and · collection of data that may be useful for research and education. An appropriately documented medical record can reduce many of the "hassles" associated with claims processing and may serve as a legal document to verify the care provided, if necessary. WHAT DO PAYERS WANT AND WHY? Because payers have a contractual obligation to enrollees, they may require reasonable documentation that services are consistent with the insurance coverage provided. They may request information to validate: · the site of service; · the medical necessity and appropriateness of the diagnostic and/or therapeutic services provided; and/or · that services provided have been accurately reported. II. GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MEDICAL RECORD DOCUMENTATION The principles of documentation listed below are applicable to all types of medical and surgical Pg. 1 services in all settings. For Evaluation and Management (E/M) services, the nature and amount of physician work and documentation varies by type of service, place of service and the patient's status. -

Pleurisy Dry and Exudative: Symptoms and Syndromes Based on Clinical-Instrumental and Laboratory Methods of Study

Topic: Pleurisy dry and exudative: symptoms and syndromes based on clinical-instrumental and laboratory methods of study. Syndrome of fluid and air accumulation in the pleural cavity in pathology of the respiratory system Objective 1. Patient S. 25 years old, has complaints of severe pain in the left half of the chest, exacerbated by deep breath, lack of air. He first felt sick 3 days ago, noticed a one-time increase in body temperature to 37,5°C. On examination: rapid superficial breathing, the left half of the chest is slower in the act of breathing. Clear pulmonary sound is determined by percussion. During auscultation, there is a pleural friction sound to the left, it is louder in the armpit. The pain increases with inhalation, decreases with lying on the side of pain. In the general clinical blood test - moderate leukocytosis, ESR - 17 mm / h. Questions: 1. What is the diagnosis? 2. What (all) data will the doctor receive when auscultating the patient's lungs with this pathology? 3. How can you distinguish the pleural friction sound from the pericardial friction sound? 4. What is the normal respiratory rate? What is the respiratory rate of rapid breathing? 5. What are the possible causes of this disease. Task 2. Patient M., 33 years old, has complaints of chills, fever up to 38,5°C for 3 days, dry cough, pain in the right half of the chest. The pain is exacerbated by breathing and coughing. Objectively: the skin is pale, the lips are cyanotic, the respiratory rate is up to 30 per minute, the right half of the chest is enlarged in volume, the intercostal spaces are smoothed. -

Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS-D Guidance Manual Effective January 1, 2019

Outcome and Assessment Information Set OASIS-D Guidance Manual Effective January 1, 2019 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services PRA Disclosure Statement According to the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, no persons are required to respond to a collection of information unless it displays a valid OMB control number. The valid OMB control number for this information collection is x. The time required to complete this information collection is estimated to average 0.3 minutes per response, including the time to review instructions, search existing data resources, gather the data needed, and complete and review the information collection. This estimate does not include time for training. If you have comments concerning the accuracy of the time estimate(s) or suggestions for improving this form, please write to: CMS, 7500 Security Boulevard, Attn: PRA Reports Clearance Officer, Mail Stop C4-26-05, Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850. *****CMS Disclaimer*****Please do not send applications, claims, payments, medical records or any documents containing sensitive information to the PRA Reports Clearance Office. Please note that any correspondence not pertaining to the information collection burden approved under the associated OMB control number listed on this form will not be reviewed, forwarded, or retained. If you have questions or concerns regarding where to submit your documents, please contact Joan Proctor National Coordinator, Home Health Quality Reporting Program Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. OASIS-D Guidance Manual Table of Contents Page -

Review of Systems

code: GF004 REVIEW OF SYSTEMS First Name Middle Name / MI Last Name Check the box if you are currently experiencing any of the following : General Skin Respiratory Arthritis/Rheumatism Abnormal Pigmentation Any Lung Troubles Back Pain (recurrent) Boils Asthma or Wheezing Bone Fracture Brittle Nails Bronchitis Cancer Dry Skin Chronic or Frequent Cough Diabetes Eczema Difficulty Breathing Foot Pain Frequent infections Pleurisy or Pneumonia Gout Hair/Nail changes Spitting up Blood Headaches/Migraines Hives Trouble Breathing Joint Injury Itching URI (Cold) Now Memory Loss Jaundice None Muscle Weakness Psoriasis Numbness/Tingling Rash Obesity Skin Disease Osteoporosis None Rheumatic Fever Weight Gain/Loss None Cardiovascular Gastrointestinal Eyes - Ears - Nose - Throat/Mouth Awakening in the night smothering Abdominal Pain Blurring Chest Pain or Angina Appetite Changes Double Vision Congestive Heart Failure Black Stools Eye Disease or Injury Cyanosis (blue skin) Bleeding with Bowel Movements Eye Pain/Discharge Difficulty walking two blocks Blood in Vomit Glasses Edema/Swelling of Hands, Feet or Ankles Chrohn’s Disease/Colitis Glaucoma Heart Attacks Constipation Itchy Eyes Heart Murmur Cramping or pain in the Abdomen Vision changes Heart Trouble Difficulty Swallowing Ear Disease High Blood Pressure Diverticulosis Ear Infections Irregular Heartbeat Frequent Diarrhea Ears ringing Pain in legs Gallbladder Disease Hearing problems Palpitations Gas/Bloating Impaired Hearing Poor Circulation Heartburn or Indigestion Chronic Sinus Trouble Shortness -

Review of Systems – Return Visit Have You Had Any Problems Related to the Following Symptoms in the Past Month? Circle Yes Or No

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS – RETURN VISIT HAVE YOU HAD ANY PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE FOLLOWING SYMPTOMS IN THE PAST MONTH? CIRCLE YES OR NO Today’s Date: ______________ Name: _______________________________ Date of Birth: __________________ GENERAL GENITOURINARY Fatigue Y N Blood in Urine Y N Fever / Chills Y N Menstrual Irregularity Y N Night Sweats Y N Painful Menstrual Cycle Y N Weight Gain Y N Vaginal Discharge Y N Weight Loss Y N Vaginal Dryness Y N EYES Vaginal Itching Y N Vision Changes Y N Painful Sex Y N EAR, NOSE, & THROAT SKIN Hearing Loss Y N Hair Loss Y N Runny Nose Y N New Skin Lesions Y N Ringing in Ears Y N Rash Y N Sinus Problem Y N Pigmentation Change Y N Sore Throat Y N NEUROLOGIC BREAST Headache Y N Breast Lump Y N Muscular Weakness Y N Tenderness Y N Tingling or Numbness Y N Nipple Discharge Y N Memory Difficulties Y N CARDIOVASCULAR MUSCULOSKELETAL Chest Pain Y N Back Pain Y N Swelling in Legs Y N Limitation of Motion Y N Palpitations Y N Joint Pain Y N Fainting Y N Muscle Pain Y N Irregular Heart Beat Y N ENDOCRINE RESPIRATORY Cold Intolerance Y N Cough Y N Heat Intolerance Y N Shortness of Breath Y N Excessive Thirst Y N Post Nasal Drip Y N Excessive Amount of Urine Y N Wheezing Y N PSYCHOLOGY GASTROINTESTINAL Difficulty Sleeping Y N Abdominal Pain Y N Depression Y N Constipation Y N Anxiety Y N Diarrhea Y N Suicidal Thoughts Y N Hemorrhoids Y N HEMATOLOGIC / LYMPHATIC Nausea Y N Easy Bruising Y N Vomiting Y N Easy Bleeding Y N GENITOURINARY Swollen Lymph Glands Y N Burning with Urination Y N ALLERGY / IMMUNOLOGY Urinary -

How to Do Chest Physical Therapy (CPT): Children, Adolescents and Adults

How to Do Chest Physical Therapy (CPT) Children, Adolescents, and Adults ©(2001, 2003, 2009) The Emily Center, Phoenix Children’s Hospital 1 2 ©(2001, 2003, 2009) The Emily Center, Phoenix Children’s Hospital Name of Child: Date:____________________ How to Do Chest Physical Therapy (CPT) Children, Adolescents, and Adults Your child needs a treatment called Chest Physical Therapy or CPT. CPT is also called Percussion and Postural Drainage (P & PD). Read this booklet to learn what CPT is and how to use it to help your child. What is CPT? Chest Physical Therapy (CPT) is something you can do to help your child breathe better. Sometimes there is too much mucus, or it is too thick. It blocks the air from moving in and out of your child’s lungs. Mucus makes it hard for your child to breathe. Mucus that sits too long in the lungs can also grow germs that can make your child sick. CPT helps to loosen your child’s mucus, so your child can cough it up. Think about how you would take Jell-O out of a mold. You tilt the mold over, then shake it and tap it to loosen the Jell-O . Mucus is like that Jell-O , and CPT helps to get it out. ©(2001, 2003, 2009) The Emily Center, Phoenix Children’s Hospital 3 Words to Learn Airways Air moves through these and into your lungs. The airways of the nose and throat lead to the big airways in the chest. The big airways branch off into smaller airways in the lungs. -

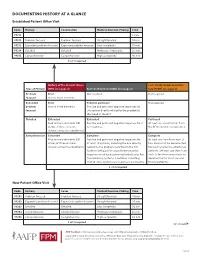

Documenting History at a Glance

DOCUMENTING HISTORY AT A GLANCE Established Patient Office Visit Code History Examination Medical Decision-Making Time 99211 — — — 5 min. 99212 Problem focused Problem focused Straightforward 10 min. 99213 Expanded problem focused Expanded problem focused Low complexity 15 min. 99214 Detailed Detailed Moderate complexity 25 min. 99215 Comprehensive Comprehensive High complexity 40 min. 2 of 3 required History of the Present Illness Past, Family and/or Social His- Type of History (HPI) (see page 2) Review of Systems (ROS) (see page 2) tory (PFSH) (see page 2) Problem Brief Not required Not required focused One to three elements Expanded Brief Problem pertinent Not required problem One to three elements Positive and pertinent negative responses for focused the system directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI. Detailed Extended Extended Pertinent Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for 2 At least one specific item from status of three or more to 9 systems. the PFSH must be documented. chronic or inactive conditions) Comprehensive Extended Complete Complete Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for At least one item from each of status of three or more at least 10 systems, including the one directly two areas must be documented chronic or inactive conditions) related to the problem identified in the HPI. for most services to established Systems with positive or pertinent negative patients. (At least one item from responses must be documented individually. For each of the three areas must be the remaining systems, a notation indicating documented for most services that all other systems are negative is permissible. -

GYNECOLOGY Helen B. Albano, MD, FPOGS Medical History • The

GYNECOLOGY Only one Helen B. Albano, MD, FPOGS Reason for admission Common gynecological complaints Medical History o Bleeding (vaginal) The quality of the medical care provided by the o Pain (specify: use 9 regions of abdomen) physician o Mass (abdominal or pelvic) Type of relationship between physician and the o Vaginal discharge patient o Urinary or GI symptoms Can be determined largely the depth of o o Protrusion out of the vagina gynecological history o Infertility Patient-Doctor Relationship o Complete history HPI (History of Present Illness) o Complete PE Refers to the chief complaint o Labs o Duration New Patient o Severity o Take Time o Precipitating factors . Obtain comprehensive history o Occurrence in relation to other events . Perform comprehensive PE . Menstrual cycle o Establish data base, along with DPR basd on . Voiding a good communication . Bowel movements Old Patient or the established patient History of similar symptoms Updates o Outcome of previous therapies . Gynecological changes Impact on the patient’s: . Pregnancy history o Quality of life . Additional surgery, accidents or new o Self-image medications o Relationship with the family (sexual history to husband) History Taking o Daily activities Overview o Most important part of gynecological Menstrual History evaluation Age of menarche o Provides tentative diagnosis (impression) Date of onset of menstrual periods before PE Duration and quantity (i.e. number of pads used per o LEGAL document . Subject to subpoena, may be day) of flow defended in court Degree of Discomfort Premenstrual symptoms General Data Cycle Name o Counted from the first day of menstrual flow Age of one cycle to the first day of menstrual Gravidity (G) flow of the next o State of being pregnant Range of normal is wide Normal range of ovulatory cycles Parity (P) o .