Bates' Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences Journal Home Page: http://www.ijmhs.net ISSN:2277-4505 Review article Examining the liver – Revisiting an old friend Cyriac Abby Philips1*, Apurva Pande2 1Department of Hepatology and Transplant Medicine, PVS Institute of Digestive Diseases, PVS Memorial Hospital, Kaloor, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2Department of Hepatology, Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, D-1, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, India. ABSTRACT In the current era of medical practice, super saturated with investigations of choice and development of diagnostic tools, clinical examination is a lost art. In this review we briefly discuss important aspects of examination of the liver, which is much needed in decision making on investigational approach. We urge the new medical student or the newly practicing physician to develop skills in clinical examination for resourceful management of the patient. KEYWORDS: Liver, examination, clinical skills, hepatomegaly, chronic liver disease, portal hypertension, liver span INTRODUCTION respiration, the excursion of liver movement is around 2 to 3 The liver attains its adult size by the age of 15 years. The cm. Castell and Frank has elegantly described normal liver liver weighs 1.2 to 1.4 kg in women and 1.4 to 1.5 kg in span in men and women utilizing the percussion method men. The liver seldom extends more than 5 cm beyond the (Table 1). Accordingly, the mean liver span is 10.5 cm for midline towards the left costal margin. During inspiration, men and 7 cm in women. During examination, a span 2 to 3 the diaphragmatic exertion moves the liver downward with cm larger or smaller than these values is considered anterior surface rotating to the right. -

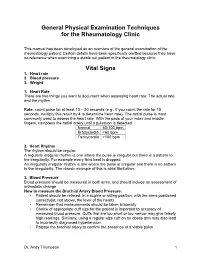

General Physical Examination Skills for Ahps

General Physical Examination Techniques for the Rheumatology Clinic This manual has been developed as an overview of the general examination of the rheumatology patient. Certain details have been specifically omitted because they have no relevance when examining a stable out patient in the rheumatology clinic. Vital Signs 1. Heart rate 2. Blood pressure 3. Weight 1. Heart Rate There are two things you want to document when assessing heart rate: The actual rate and the rhythm. Rate: count pulse for at least 15 – 30 seconds (e.g., if you count the rate for 15 seconds, multiply this result by 4 to determine heart rate). The radial pulse is most commonly used to assess the heart rate. With the pads of your index and middle fingers, compress the radial artery until a pulsation is detected. Normal 60-100 bpm Bradycardia <60 bpm Tachycardia >100 bpm 2. Heart Rhythm The rhythm should be regular. A regularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular but there is a pattern to the irregularity. For example every third beat is dropped. An irregularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular and there is no pattern to the irregularity. The classic example of this is atrial fibrillation. 3. Blood Pressure Blood pressure should be measured in both arms, and should include an assessment of orthostatic change How to measure the Brachial Artery Blood Pressure: • Patient should be relaxed, in a supine or sitting position, with the arms positioned correctly(at, not above, the level of the heart) • Remember that measurements should be taken bilaterally • Choice of appropriate cuff size for the patient is important to accuracy of measured blood pressure. -

HEENT EXAMINIATION ______HEENT Exam Exam Overview

HEENT EXAMINIATION ____________________________________________________________ HEENT Exam Exam Overview I. Head A. Visual inspection B. Palpation of scalp II. Eyes A. Visual Acuity B. Visual Fields C. Extraocular Movements/Near Response D. Inspection of sclera & conjunctiva E. Pupils F. Ophthalmoscopy III. Ears A. External Inspection B. Otoscopy C. Hearing Acuity D. Weber/Rinne IV. Nose A. External Inspection B. Speculum/otoscope C. Sinus areas V. Throat/Mouth A. Mouth Examination B. Pharynx Examination C. Bimanual Palpation VI. Neck A. Lymph nodes B. Thyroid gland 29 HEENT EXAMINIATION ____________________________________________________________ HEENT Terms Acuity – (ehk-yu-eh-tee) sharpness, clearness, and distinctness of perception or vision. Accommodation - adjustment, especially of the eye for seeing objects at various distances. Miosis – (mi-o-siss) constriction of the pupil of the eye, resulting from a normal response to an increase in light or caused by certain drugs or pathological conditions. Conjunctiva – (kon-junk-ti-veh) the mucous membrane lining the inner surfaces of the eyelids and anterior part of the sclera. Sclera – (sklehr-eh) the tough fibrous tunic forming the outer envelope of the eye and covering all of the eyeball except the cornea. Cornea – (kor-nee-eh) clear, bowl-shaped structure at the front of the eye. It is located in front of the colored part of the eye (iris). The cornea lets light into the eye and partially focuses it. Glaucoma – (glaw-ko-ma) any of a group of eye diseases characterized by abnormally high intraocular fluid pressure, damaged optic disk, hardening of the eyeball, and partial to complete loss of vision. Conductive hearing loss - a hearing impairment of the outer or middle ear, which is due to abnormalities or damage within the conductive pathways leading to the inner ear. -

Central Venous Pressure Venous Examination but Underestimates Ultrasound Accurately Reflects the Jugular

Ultrasound Accurately Reflects the Jugular Venous Examination but Underestimates Central Venous Pressure Gur Raj Deol, Nicole Collett, Andrew Ashby and Gregory A. Schmidt Chest 2011;139;95-100; Prepublished online August 26, 2010; DOI 10.1378/chest.10-1301 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services can be found online on the World Wide Web at: http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/139/1/95.full.html Chest is the official journal of the American College of Chest Physicians. It has been published monthly since 1935. Copyright2011by the American College of Chest Physicians, 3300 Dundee Road, Northbrook, IL 60062. All rights reserved. No part of this article or PDF may be reproduced or distributed without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. (http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml) ISSN:0012-3692 Downloaded from chestjournal.chestpubs.org at UCSF Library & CKM on January 21, 2011 © 2011 American College of Chest Physicians CHEST Original Research CRITICAL CARE Ultrasound Accurately Refl ects the Jugular Venous Examination but Underestimates Central Venous Pressure Gur Raj Deol , MD ; Nicole Collett , MD ; Andrew Ashby , MD ; and Gregory A. Schmidt , MD , FCCP Background: Bedside ultrasound examination could be used to assess jugular venous pressure (JVP), and thus central venous pressure (CVP), more reliably than clinical examination. Methods: The study was a prospective, blinded evaluation comparing physical examination of external jugular venous pressure (JVPEXT), internal jugular venous pressure (JVPINT), and ultrasound collapse pressure (UCP) with CVP measured using an indwelling catheter. We com- pared the examination of the external and internal JVP with each other and with the UCP and CVP. -

CASE REPORT 48-Year-Old Man

THE PATIENT CASE REPORT 48-year-old man SIGNS & SYMPTOMS – Acute hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear Dennerd Ovando, MD; J. Walter Kutz, MD; Weber test lateralized to the – Sergio Huerta, MD right ear Department of Surgery (Drs. Ovando and Huerta) – Positive Rinne test and and Department of normal tympanometry Otolaryngology (Dr. Kutz), UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; VA North Texas Health Care System, Dallas (Dr. Huerta) Sergio.Huerta@ THE CASE UTSouthwestern.edu The authors reported no A healthy 48-year-old man presented to our otolaryngology clinic with a 2-hour history of potential conflict of interest hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the left ear. He denied any vertigo, nausea, vomiting, relevant to this article. otalgia, or otorrhea. He had noticed signs of a possible upper respiratory infection, including a sore throat and headache, the day before his symptoms started. His medical history was unremarkable. He denied any history of otologic surgery, trauma, or vision problems, and he was not taking any medications. The patient was afebrile on physical examination with a heart rate of 48 beats/min and blood pressure of 117/68 mm Hg. A Weber test performed using a 512-Hz tuning fork lateral- ized to the right ear. A Rinne test showed air conduction was louder than bone conduction in the affected left ear—a normal finding. Tympanometry and otoscopic examination showed the bilateral tympanic membranes were normal. THE DIAGNOSIS Pure tone audiometry showed severe sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear and a poor speech discrimination score. The Weber test confirmed the hearing loss was sensorineu- ral and not conductive, ruling out a middle ear effusion. -

The Older Adult 20

CHAPTER The Older Adult 20 Older adults now number more than 25 million people in the United States and are expected to reach 80 million by 2050.1 These seniors will live longer than previous generations: life span at birth is currently 79 years for women and 74 years for men. Those older than 85 years are projected to increase to 5% of the U.S. population within 40 years. Hence, the “demographic im- perative” is to maximize not only the life span but also the “health span” of our older population, so that seniors maintain full function for as long as possible, enjoying rich and active lives in their homes and communities. Clinicians now recognize frailty as one of society’s common myths about aging—more than 95% of Americans older than 65 years live in the commu- nity, and only 5% reside in long-term care facilities.1,2 Over the past 20 years, seniors actually have become more active and less disabled. These changes call for new goals for clinical care—“an informed activated patient inter- acting with a prepared proactive team, resulting in high quality satisfying en- counters and improved outcomes”3—and a distinct set of clinical attitudes and skills. CHAPTER 20 I THE OLDER ADULT 839 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY Assessing the older adult presents special opportunities and special challenges. Many of these are quite different from the disease-oriented approach of his- tory taking and physical examination for younger patients: the focus on healthy or “successful” aging; the need to understand and mobilize family, social, and community supports; the importance of skills directed to func- tional assessment, “the sixth vital sign”; and the opportunities for promoting the older adult’s long-term health and safety. -

Practical Cardiac Auscultation

LWW/CCNQ LWWJ306-08 March 7, 2007 23:32 Char Count= Crit Care Nurs Q Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 166–180 Copyright c 2007 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Practical Cardiac Auscultation Daniel M. Shindler, MD, FACC This article focuses on the practical use of the stethoscope. The art of the cardiac physical exam- ination includes skillful auscultation. The article provides the author’s personal approach to the patient for the purpose of best hearing, recognizing, and interpreting heart sounds and murmurs. It should be used as a brief introduction to the art of auscultation. This article also attempts to illustrate heart sounds and murmurs by using words and letters to phonate the sounds, and by presenting practical clinical examples where auscultation clearly influences cardiac diagnosis and treatment. The clinical sections attempt to go beyond what is available in standard textbooks by providing information and stethoscope techniques that are valuable and useful at the bedside. Key words: auscultation, murmur, stethoscope HIS article focuses on the practical use mastered at the bedside. This article also at- T of the stethoscope. The art of the cardiac tempts to illustrate heart sounds and mur- physical examination includes skillful auscul- murs by using words and letters to phonate tation. Even in an era of advanced easily avail- the sounds, and by presenting practical clin- able technological bedside diagnostic tech- ical examples where auscultation clearly in- niques such as echocardiography, there is still fluences cardiac diagnosis and treatment. We an important role for the hands-on approach begin by discussing proper stethoscope selec- to the patient for the purpose of evaluat- tion and use. -

Current Audiometric Tests for the Detection of Functional Hearing Loss

CURRENT AUDIOMETRIC TESTS FOR THE DETECTION OF FUNCTIONAL HEARING LOSS by JOAN PHYLLIS COOPER X^^ Be A., Union College, 1965 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the J requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1963 Approved by: Ma j or ? ro re s s or . bo 11 C6£ TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I , Introduction .••••••••••••••••••«••• • • • 1 Definitions ....?................«« •••••••• 2 II. Tests for Functional Hearing Loss 4 General Behavior in the Clinical Evaluation 4 The Ear, Nose, and Throat Examination 9 Pure-tone Audiometry 12 Saucer-shaped Audiograms 14 False-alarm Responses During Pure-tone Audiometry ...................... c 17 Inappropriate Lateralization ,« 17 Bone Conduction Audiometry 20 Speech Audiometry ••••••••••••••••• • 22 Speech Discrimination ••••••••••• 22 Speech Reception Threshold ........ ............... 23 Errors During Measurement of Spondee Threshold ... 2 3 Inappropriate Lateralization 26 Pure-tone Stenger Test 26 Modified (Speech) Stenger Test 29 Doerf ler-Stewart Test 30 Lombard Test ............ o 36 De layed Auditory Feedback ., 39 Psychogalvanic Skin Resistance Test 45 Modification of EDR Test , . .. 50 Bekesy Type V Tracing ......... o ..... ....... ... s ...... 51 c ^ . iii Chapter Page ( II. Rainville Test 5S Sensorineural Acuity Level Test ..... 59 Lipreading Test .....«•..•.<.«•......,....•............ 61 The Variable Intensity Pulse Count Method 62 Rapid Random Loudness Judgments ..................... c 63 Middle Ear -

1- Assessing Pain

Foundations of Assessing and Treating Pain Assessing Pain Table of Contents Assessing Pain........................................................................................................................................2 Goal:..............................................................................................................................................2 After completing this module, participants will be able to:..............................................................2 Professional Practice Gaps............................................................................................................2 Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 2 Assessment and Diagnosis of Pain Case: Ms. Ward..........................................................................3 Confidentiality..........................................................................................................................................4 Pain History: A Standardized Approach..................................................................................................4 Evaluating Pain Using PQRSTU: Steps P, Q, R, S T, and U..............................................................5 Ms. Ward's Pain History (P, Q, R, S, T, U)..........................................................................................6 Video: Assessing Pain Systematically with PQRTSTU Acronym........................................................8 -

Medical Staff Medical Record Policy

Number: MS -012 Effective Date: September 26, 2016 BO Revised:11/28/2016; 11/27/2017; 1/22/2018; 8/27/2018 CaroMont Regional Medical Center Author: Approved: Patrick Russo, MD, Chief-of-Staff Authorized: Todd Davis, MD, EVP, GMO MEDICAL STAFF MEDICAL RECORD POLICY 1. REQUIRED COMPONENTS OF THE MEDICAL RECORD The medical record shall include information to support the patient's diagnosis and condition, justify the patient's care, treatment and services, and document the course and result of the patient's care, and services to promote continuity of care among providers. The components may consist of the following: identification data, history and physical examination, consultations, clinical laboratory findings, radiology reports, procedure and anesthesia consents, medical or surgical treatment, operative report, pathological findings, progress notes, final diagnoses, condition on discharge, autopsy report when performed, other pertinent information and discharge summary. 2. ADMISSION HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION FOR HOSPITAL CARE Please refer to CaroMont Regional Medical Center Medical Staff Bylaws, Section 12.E. A. The history and physical examination (H&P), when required, shall be performed and recorded by a physician, dentist, podiatrist, or privileged practitioner who has an active NC license and has been granted privileges by the hospital. The H&P is the responsibility of the attending physician or designee. Oral surgeons, dentists, and podiatrists are responsible for the history and physical examination pertinent to their area of specialty. B. If a physician has delegated the responsibility of completing or updating an H&P to a privileged practitioner who has been granted privileges to do H&Ps, the H&P and/or update must be countersigned by the supervisor physician within 30 days after discharge to complete the medi_cal record. -

GUIDELINES for WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY and PHYSICALS

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS by Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N, C.S., A.N.P, F.N.P. © 2001 NPCEU Inc. all rights reserved NPCEU INC. PO Box 246 Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-537-9767 - FAX 908-537-6409 www.npceu.com Copyright © 2001 NPCEU Inc. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage, or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission of the publisher: NPCEU, Inc. PO Box 246, Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-527-9767, Fax 908-527-6409. Bulk Purchase Discounts. For discounts on orders of 20 copies or more, please fax the number above or write the address above. Please state if you are a non-profit organization and the number of copies you are interested in purchasing. 2 GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N., C.S., A.N.P., F.N.P. Written documentation for clinical management of patients within health care settings usually include one or more of the following components. - Problem Statement (Chief Complaint) - Subjective (History) - Objective (Physical Exam/Diagnostics) - Assessment (Diagnoses) - Plan (Orders) - Rationale (Clinical Decision Making) Expertise and quality in clinical write-ups is somewhat of an art-form which develops over time as the student/practitioner gains practice and professional experience. In general, students are encouraged to review patient charts, reading as many H/Ps, progress notes and consult reports, as possible. In so doing, one gains insight into a variety of writing styles and methods of conveying clinical information. -

Topic: MITRAL HEART DISEASES: BASIC SYMPTOMS and SYNDROMES on the BASIS of CLINICAL and INSTRUMENTAL METHODS of EXAMINATION

Topic: MITRAL HEART DISEASES: BASIC SYMPTOMS AND SYNDROMES ON THE BASIS OF CLINICAL AND INSTRUMENTAL METHODS OF EXAMINATION 1. What hemodynamic changes cause complaints of patients with mitral stenosis for cough, shortness of breath, hemoptysis? A. reduction of systemic blood pressure; B. increased pressure in the small circulatory system; C. stagnation of blood in the liver; D. enlargement of the left atrium and contraction of the mediastinum; E. Reduction of blood flow from the left ventricle. 2. What complaints are caused by a decrease in minute volume of blood in patients with mitral stenosis? A) cough, shortness of breath, hemoptysis; C) fever, joint pain, general weakness; C) heartache, heart failure, palpitations; D) lower extremity swelling, heaviness in the right hypochondrium; E) headache, dizziness, general weakness, fatigue. 3. Data palpation of the heart area with mitral stenosis: A) no change is observed; B) apex beat displaced to the left, resistant; C) apex beat weakened or undetectable; D) there is an increased pulsation in the second intercostal space to the left; E) there is a systolic "cat murmur" in the second intercostal space to the right. 4. What forced position can occupy a patient with mitral stenosis? A) knee-elbow; B) a Bedouin who prays; C) orthopnoe; D) opistotonus; E) outside the pointing dog 5. What does the face of a patient with mitral stenosis look like? A) swollen, cyanotic; B) swollen, pale, enophthalmos observed; C) the face of a "wax doll"; D) swollen, pale, with swelling under and above the eyes; E) pale, with cyanotic blush, cyanosis of the tip of the nose, ear lobes, chin.