Running Head: COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Systems

code: GF004 REVIEW OF SYSTEMS First Name Middle Name / MI Last Name Check the box if you are currently experiencing any of the following : General Skin Respiratory Arthritis/Rheumatism Abnormal Pigmentation Any Lung Troubles Back Pain (recurrent) Boils Asthma or Wheezing Bone Fracture Brittle Nails Bronchitis Cancer Dry Skin Chronic or Frequent Cough Diabetes Eczema Difficulty Breathing Foot Pain Frequent infections Pleurisy or Pneumonia Gout Hair/Nail changes Spitting up Blood Headaches/Migraines Hives Trouble Breathing Joint Injury Itching URI (Cold) Now Memory Loss Jaundice None Muscle Weakness Psoriasis Numbness/Tingling Rash Obesity Skin Disease Osteoporosis None Rheumatic Fever Weight Gain/Loss None Cardiovascular Gastrointestinal Eyes - Ears - Nose - Throat/Mouth Awakening in the night smothering Abdominal Pain Blurring Chest Pain or Angina Appetite Changes Double Vision Congestive Heart Failure Black Stools Eye Disease or Injury Cyanosis (blue skin) Bleeding with Bowel Movements Eye Pain/Discharge Difficulty walking two blocks Blood in Vomit Glasses Edema/Swelling of Hands, Feet or Ankles Chrohn’s Disease/Colitis Glaucoma Heart Attacks Constipation Itchy Eyes Heart Murmur Cramping or pain in the Abdomen Vision changes Heart Trouble Difficulty Swallowing Ear Disease High Blood Pressure Diverticulosis Ear Infections Irregular Heartbeat Frequent Diarrhea Ears ringing Pain in legs Gallbladder Disease Hearing problems Palpitations Gas/Bloating Impaired Hearing Poor Circulation Heartburn or Indigestion Chronic Sinus Trouble Shortness -

Review of Systems – Return Visit Have You Had Any Problems Related to the Following Symptoms in the Past Month? Circle Yes Or No

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS – RETURN VISIT HAVE YOU HAD ANY PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE FOLLOWING SYMPTOMS IN THE PAST MONTH? CIRCLE YES OR NO Today’s Date: ______________ Name: _______________________________ Date of Birth: __________________ GENERAL GENITOURINARY Fatigue Y N Blood in Urine Y N Fever / Chills Y N Menstrual Irregularity Y N Night Sweats Y N Painful Menstrual Cycle Y N Weight Gain Y N Vaginal Discharge Y N Weight Loss Y N Vaginal Dryness Y N EYES Vaginal Itching Y N Vision Changes Y N Painful Sex Y N EAR, NOSE, & THROAT SKIN Hearing Loss Y N Hair Loss Y N Runny Nose Y N New Skin Lesions Y N Ringing in Ears Y N Rash Y N Sinus Problem Y N Pigmentation Change Y N Sore Throat Y N NEUROLOGIC BREAST Headache Y N Breast Lump Y N Muscular Weakness Y N Tenderness Y N Tingling or Numbness Y N Nipple Discharge Y N Memory Difficulties Y N CARDIOVASCULAR MUSCULOSKELETAL Chest Pain Y N Back Pain Y N Swelling in Legs Y N Limitation of Motion Y N Palpitations Y N Joint Pain Y N Fainting Y N Muscle Pain Y N Irregular Heart Beat Y N ENDOCRINE RESPIRATORY Cold Intolerance Y N Cough Y N Heat Intolerance Y N Shortness of Breath Y N Excessive Thirst Y N Post Nasal Drip Y N Excessive Amount of Urine Y N Wheezing Y N PSYCHOLOGY GASTROINTESTINAL Difficulty Sleeping Y N Abdominal Pain Y N Depression Y N Constipation Y N Anxiety Y N Diarrhea Y N Suicidal Thoughts Y N Hemorrhoids Y N HEMATOLOGIC / LYMPHATIC Nausea Y N Easy Bruising Y N Vomiting Y N Easy Bleeding Y N GENITOURINARY Swollen Lymph Glands Y N Burning with Urination Y N ALLERGY / IMMUNOLOGY Urinary -

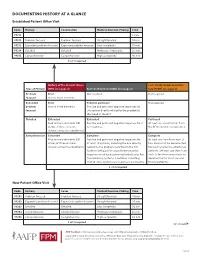

Documenting History at a Glance

DOCUMENTING HISTORY AT A GLANCE Established Patient Office Visit Code History Examination Medical Decision-Making Time 99211 — — — 5 min. 99212 Problem focused Problem focused Straightforward 10 min. 99213 Expanded problem focused Expanded problem focused Low complexity 15 min. 99214 Detailed Detailed Moderate complexity 25 min. 99215 Comprehensive Comprehensive High complexity 40 min. 2 of 3 required History of the Present Illness Past, Family and/or Social His- Type of History (HPI) (see page 2) Review of Systems (ROS) (see page 2) tory (PFSH) (see page 2) Problem Brief Not required Not required focused One to three elements Expanded Brief Problem pertinent Not required problem One to three elements Positive and pertinent negative responses for focused the system directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI. Detailed Extended Extended Pertinent Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for 2 At least one specific item from status of three or more to 9 systems. the PFSH must be documented. chronic or inactive conditions) Comprehensive Extended Complete Complete Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for At least one item from each of status of three or more at least 10 systems, including the one directly two areas must be documented chronic or inactive conditions) related to the problem identified in the HPI. for most services to established Systems with positive or pertinent negative patients. (At least one item from responses must be documented individually. For each of the three areas must be the remaining systems, a notation indicating documented for most services that all other systems are negative is permissible. -

Sleep Medicine Curriculum for Neurology Residents

Sleep Medicine Curriculum for Neurology Residents This curriculum, developed in collaboration with the AAN Consortium of Neurology Program Directors and Graduate Education Subcommittee, provides a comprehensive outline of the relevant educational goals for the future generation of adult neurologists learning sleep medicine during residency. The clinical scope of this curriculum is common and uncommon sleep disorders encountered in typical neurology practices. While the all-encompassing scope of this outline covers more than is expected to be learned by neurology residents on a given subspecialty rotation, the measurable objectives are included to provide program directors and other rotation developers the means of evaluating whether a minimum competence in sleep was attained in any combination of specific areas. Finally, as sleep medicine is a cross-disciplinary neurologic subspecialty, the curriculum ends with a table highlighting overlapping conditions between major sleep disorder categories and neurologic subspecialities. Authors: Lead Author Logan Schneider, MD [email protected] Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Center Alon Avidan, MD, MPH, FAAN David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA Muna Irfan, MD University of Minnesota Meena Khan, MD The Ohio State University Created: January 2020 Effective: February 2020 to February 2021 Approved by the American Academy of Neurology’s Graduate Education Subcommittee Sleep Medicine Curriculum for Neurology Residents Part I. General Clinical Approach Clinical evaluation: History Efficiently obtains a complete, relevant, and organized neurologic history Performs comprehensive review of systems pertinent to ICSD-3 sleep-wake disorder categories (sleep-related disordered breathing, hypersomnias, insomnias, parasomnias, sleep-related movement disorders, circadian disorders) Performs comprehensive review of systems probing medical conditions that are known to impact sleep-wake disorders (e.g. -

Review of Systems Health History Sheet Patient: ______DOB: ______Age: ______Gender: M / F

603 28 1/4 Road Grand Junction, CO 81506 (970) 263-2600 Review of Systems Health History Sheet Patient: _________________ DOB: ____________ Age: ______ Gender: M / F Please mark any symptoms you are experiencing that are related to your complaint today: Allergic/ Immunologic Ears/Nose/Mouth/Throat Genitourinary Men Only Frequent Sneezing Bleeding Gums Pain with Urinating Pain/Lump in Testicle Hives Difficulty Hearing Blood in Urine Penile Itching, Itching Dizziness Difficulty Urinating Burning or Discharge Runny Nose Dry Mouth Incomplete Emptying Problems Stopping or Sinus Pressure Ear Pain Urinary Frequency Starting Urine Stream Cardiovascular Frequent Infections Loss of Urinary Control Waking to Urinate at Chest Pressure/Pain Frequent Nosebleeds Hematologic / Lymphatic Night Chest Pain on Exertion Hoarseness Easy Bruising / Bleeding Sexual Problems / Irregular Heart Beats Mouth Breathing Swollen Glands Concerns Lightheaded Mouth Ulcers Integumentary (Skin) History of Sexually Swelling (Edema) Nose/Sinus Problems Changes in Moles Transmitted Diseases Shortness of Breath Ringing in Ears Dry Skin Women Only When Lying Down Endocrine Eczema Bleeding Between Shortness of Breath Increased Thirst / Growth / Lesions Periods When Walking Urination Itching Heavy Periods Constitutional Heat/Cold Intolerance Jaundice (Yellow Extreme Menstrual Pain Exercise Intolerance Gastrointestinal Skin or Eyes) Vaginal Itching, Fatigue Abdominal Pain Rash Burning or Discharge Fever Black / Tarry Stool Respiratory Waking to Urinate at Weight Gain (___lbs) Blood -

Paramedic Instructional Guidelines Preparatory EMS Systems

National Emergency Medical Services Education Standards Paramedic Instructional Guidelines Preparatory EMS Systems Paramedic Education Standard Integrates comprehensive knowledge of EMS systems, safety/well being of the paramedic, and medical/legal and ethical issues, which is intended to improve the health of EMS personnel, patients, and the community. Paramedic-Level Instructional Guideline The Paramedic Instructional Guidelines in this section include all the topics and material at the AEMT level PLUS the following material: I. History of EMS A. EMS Prior to World War I 1. 1485 – Siege of Malaga, first recorded use of ambulance by military, no medical care provided 2. 1800s – Napoleon designated vehicle and attendant to head to battle field a. 1860 – first recorded use of medic and ambulance use in the United States b. 1865 – first civilian ambulance, Commercial Hospital of Cincinnati, Ohio c. 1869 – First ambulance service, Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY d. 1899 – Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago operates automobile ambulance B. EMS Between World War I and II 1. 1900s – Hospitals place interns on ambulances, first real attempt at quality scene and transport care 2. 1926 – Phoenix Fire Department enters EMS 3. 1928 – First rescue squad launched in Roanoke, VA. Squad implemented by Julien Stanley Wise and named Roanoke Life Saving Crew 4. 1940s a. Many hospital-based ambulance services shut down due to lack of manpower resulting from WWI b. City governments turn service over to police and fire departments c. No laws on minimum training d. Ambulance attendance became a form of punishment in many fire depts. C. Post-World War II 1. -

Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Second Edition 1 WORK GROUP ON PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION Michael J. Vergare, M.D., Chair Renée L. Binder, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Marc Galanter, M.D. Francis G. Lu, M.D. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. Joel Yager, M.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Robert Pyles, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Roger Peele, M.D. (Area III) Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. (Area IV) John P. D. Shemo, M.D. (Area V) Lawrence Lurie, M.D. (Area VI) R. Dale Walker, M.D. (Area VII) Mary Ann Barnovitz, M.D. Sheila Hafter Gray, M.D. Sunil Saxena, M.D. Tina Tonnu, M.D. STAFF Robert Kunkle, M.A., Senior Program Manager Amy B. Albert, B.A., Assistant Project Manager Laura J. Fochtmann, M.D., Medical Editor Claudia Hart, Director, Department of Quality Improvement and Psychiatric Services Darrel A. Regier, M.D., M.P.H., Director, Division of Research This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in June 2006. 2 APA Practice Guidelines CONTENTS Statement of Intent. Development Process . Introduction . I. Purpose of Evaluation. A. General Psychiatric Evaluation . B. Emergency Evaluation . C. Clinical Consultation. D. Other Consultations . II. Site of the Clinical Evaluation . -

History & Physical Format

History & Physical Format SUBJECTIVE (History) Identification name, address, tel.#, DOB, informant, referring provider CC (chief complaint) list of symptoms & duration. reason for seeking care HPI (history of present illness) - PQRST Provocative/palliative - precipitating/relieving Quality/quantity - character Region - location/radiation Severity - constant/intermittent Timing - onset/frequency/duration PMH (past medical /surgical history) general health, weight loss, hepatitis, rheumatic fever, mono, flu, arthritis, Ca, gout, asthma/COPD, pneumonia, thyroid dx, blood dyscrasias, ASCVD, HTN, UTIs, DM, seizures, operations, injuries, PUD/GERD, hospitalizations, psych hx Allergies Meds (Rx & OTC) SH (social history) birthplace, residence, education, occupation, marital status, ETOH, smoking, drugs, etc., sexual activity - MEN, WOMEN or BOTH CAGE Review Ever Feel Need to CUT DOWN Ever Felt ANNOYED by criticism of drinking Ever Had GUILTY Feelings Ever Taken Morning EYE OPENER FH (family history) age & cause of death of relatives' family diseases (CAD, CA, DM, psych) SUBJECTIVE (Review of Systems) skin, hair, nails - lesions, rashes, pruritis, changes in moles; change in distribution; lymph nodes - enlargement, pain bones , joints muscles - fractures, pain, stiffness, weakness, atrophy blood - anemia, bruising head - H/A, trauma, vertigo, syncope, seizures, memory eyes- visual loss, diplopia, trauma, inflammation glasses ears - deafness, tinnitis, discharge, pain nose - discharge, obstruction, epistaxis mouth - sores, gingival bleeding, teeth, -

Foundations of Physical Examination and History Taking

UNIT I Foundations of Physical Examination and History Taking CHAPTER 1 Overview of Physical Examination and History Taking CHAPTER 2 Interviewing and The Health History CHAPTER 3 Clinical Reasoning, Assessment, and Plan CHAPTER Overview of 1 Physical Examination and History Taking The techniques of physical examination and history taking that you are about to learn embody time-honored skills of healing and patient care. Your ability to gather a sensitive and nuanced history and to perform a thorough and accurate examination deepens your relationships with patients, focuses your assessment, and sets the direction of your clinical thinking. The qual- ity of your history and physical examination governs your next steps with the patient and guides your choices from among the initially bewildering array of secondary testing and technology. Over the course of becoming an ac- complished clinician, you will polish these important relational and clinical skills for a lifetime. As you enter the realm of patient assessment, you begin integrating the es- sential elements of clinical care: empathic listening; the ability to interview patients of all ages, moods, and backgrounds; the techniques for examining the different body systems; and, finally, the process of clinical reasoning. Your experience with history taking and physical examination will grow and ex- pand, and will trigger the steps of clinical reasoning from the first moments of the patient encounter: identifying problem symptoms and abnormal find- ings; linking findings to an underlying process of pathophysiology or psycho- pathology; and establishing and testing a set of explanatory hypotheses. Working through these steps will reveal the multifaceted profile of the patient before you. -

Review of Systems – Clinician Documentation Aug 2019

Review of Systems – Clinician Documentation Aug 2019 WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW: Review of Systems (ROS) is an inventory of body systems obtained by asking a series of questions to identify signs and/or symptoms the patient may be experiencing or has experienced. CMS and Payers have varying documentation audit focal points for clinical validation of services rendered. Points are not synonymous with symptoms. What are the systems recognized 1. Constitutional Symptoms (for example: fever, weight loss) for ROS? 2. Eyes 3. Ears, nose, mouth, throat 4. Cardiovascular 5. Respiratory 6. Gastrointestinal 7. Genitourinary What are the three types of ROS? 1. Problem pertinent 2. Extended 3. Complete What is required for each type 1. Problem Pertinent ROS inquires about the system directly related to the problem ROS? identified in the History of Physical Illness (HPI). 2. Extended ROS inquires about the system directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI and a limited number (two to nine) of additional systems. 3. Complete ROS inquires about the system(s) directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI plus all additional (minimum of ten) organ systems. You must individually document those systems with positive or pertinent negative responses. For the remaining systems, a notation indicating all other systems are negative is permissible. Documentation Requirements Documentation within the patient record should support the level of service billed. For every service billed, you must indicate the specific sign, symptom, or patient complaint that makes the service reasonable and medically necessary. It would be inappropriate and likely ruled not medically necessary to bill based on a full review of systems for a problem focused complaint. -

HISTORY of PRESENT ILLNESS ELEMENTS: Location Timing Quality Context Severity Modifying Factors Duration Associated Signs/Symptoms

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS ELEMENTS: Location Timing Quality Context Severity Modifying Factors Duration Associated Signs/Symptoms REVIEW OF SYSTEMS (ROS): Constitutional Integumentary (skin and/or breast) Eyes Neurological ENT, including mouth Psychiatric Cardiovascular Endocrine Genitourinary Respiratory Gastrointestinal Hematologic/Lymphatic Musculoskeletal Allergic/Immunologic PHYSICAL EXAM: BODY AREAS: ORGAN SYSTEMS: Head (including face) Constitutional Musculoskeletal Neck Eyes Skin Chest (including Breasts & ENT and mouth Neurologic Axillae) Abdomen Cardiovascular Psychiatric Genitalia, groin, buttocks Respiratory Hematologic/ Back (including spine) Gastrointestinal Lymphatic/ Each Extremity Genitourinary Immunologic 1995 coding guidelines count Body Areas and/or Organ Systems 1997 coding guidelines count bullets from General Multi-System Examination or Single Organ System Exam HPI/ROS HPI: History of Present Illness Location: where in/on the body the problem, symptom or pain occurs, eg. Area of body, bilateral, unilateral, left, right, anterior, posterior, upper, lower, diffuse or localized, fixed or migratory, radiating to other areas. Quality: an adjective describing the type of problem, symptom or pain, eg. Dull, sharp, throbbing, constant, intermittent, itching, stabbing, acute, chronic, improving or worsening, red or swollen, cramping shooting, scratchy Severity: patient’s nonverbal actions or verbal description as to the degree/extent of the problem, symptom or pain: pain scale 0 to 10, comparison of the current problem, symptom or pain to previous experiences, severity itself is considered a quality. Duration: how long the problem, symptom or pain has been present or how long the problem, symptom or pain lasts, eg. Since last night, for the past week, until today, it lasted for 2 hours Timing: describes when the pain occurs eg. -

Guidelines for Writeups Principles Organization

Guidelines for Writeups by Steve McGee, M.D. Principles 1. Purpose of the write-up 1. to record your patientís story in a concise, legible and well-organized manner 2. to demonstrate your fund of knowledge and problem-solving skills 2. Although there is no single authority on write-ups, these guidelines will help you avoid common mistakes. Further specific feedback from your teachers will illustrate the diversity of styles used in the successful write-up. 3. Overall length should be 3 – 6 pages. 4. The write-up’s basic structure (suggested length of each section) 1. Identifying information/chief complaint (1 – 2 lines) 2. History of present illness (½ - 1 ½ pages) 3. Past medical history (¼ - 1 page) 4. Family history (5 – 10 lines) 5. Social history (5 – 10 lines) 6. Review of systems (¼ - ½ page) 7. Physical examination (½ - 1 ½ pages) 8. Laboratory (¼ - ½ page) 9. Assessment/Plan (½ - 1 ½ pages) Organization 1. Identifying information/chief complaint (II/CC) "a 27 yo man with acute lymphocytic leukemia presents with 3 days of fever and chills" (specific infections affect patients with leukemia) "a 64 yo woman with diabetes and steroid-dependent chronic obstructive lung disease presents with dysuria and hematuria" (diabetes and lung disease will require active management in the hospital) "a 54 yo man with nephrolithiasis in 1982 who presents with acute shortness of breath" (the nephrolithiasis is neither active nor relevant and belongs in PMH, not the II/CC) 1. Principle: include the patient’s 1. age 2. sex 3. country of origin or race (if relevant) 4. other active and relevant medical problems (no more than 4) 5.