Guidelines for Writeups Principles Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences

International Journal of Medical and Health Sciences Journal Home Page: http://www.ijmhs.net ISSN:2277-4505 Review article Examining the liver – Revisiting an old friend Cyriac Abby Philips1*, Apurva Pande2 1Department of Hepatology and Transplant Medicine, PVS Institute of Digestive Diseases, PVS Memorial Hospital, Kaloor, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2Department of Hepatology, Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, D-1, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, India. ABSTRACT In the current era of medical practice, super saturated with investigations of choice and development of diagnostic tools, clinical examination is a lost art. In this review we briefly discuss important aspects of examination of the liver, which is much needed in decision making on investigational approach. We urge the new medical student or the newly practicing physician to develop skills in clinical examination for resourceful management of the patient. KEYWORDS: Liver, examination, clinical skills, hepatomegaly, chronic liver disease, portal hypertension, liver span INTRODUCTION respiration, the excursion of liver movement is around 2 to 3 The liver attains its adult size by the age of 15 years. The cm. Castell and Frank has elegantly described normal liver liver weighs 1.2 to 1.4 kg in women and 1.4 to 1.5 kg in span in men and women utilizing the percussion method men. The liver seldom extends more than 5 cm beyond the (Table 1). Accordingly, the mean liver span is 10.5 cm for midline towards the left costal margin. During inspiration, men and 7 cm in women. During examination, a span 2 to 3 the diaphragmatic exertion moves the liver downward with cm larger or smaller than these values is considered anterior surface rotating to the right. -

General Physical Examination Skills for Ahps

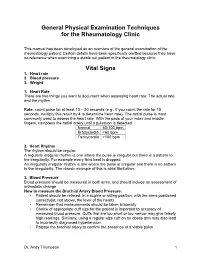

General Physical Examination Techniques for the Rheumatology Clinic This manual has been developed as an overview of the general examination of the rheumatology patient. Certain details have been specifically omitted because they have no relevance when examining a stable out patient in the rheumatology clinic. Vital Signs 1. Heart rate 2. Blood pressure 3. Weight 1. Heart Rate There are two things you want to document when assessing heart rate: The actual rate and the rhythm. Rate: count pulse for at least 15 – 30 seconds (e.g., if you count the rate for 15 seconds, multiply this result by 4 to determine heart rate). The radial pulse is most commonly used to assess the heart rate. With the pads of your index and middle fingers, compress the radial artery until a pulsation is detected. Normal 60-100 bpm Bradycardia <60 bpm Tachycardia >100 bpm 2. Heart Rhythm The rhythm should be regular. A regularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular but there is a pattern to the irregularity. For example every third beat is dropped. An irregularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular and there is no pattern to the irregularity. The classic example of this is atrial fibrillation. 3. Blood Pressure Blood pressure should be measured in both arms, and should include an assessment of orthostatic change How to measure the Brachial Artery Blood Pressure: • Patient should be relaxed, in a supine or sitting position, with the arms positioned correctly(at, not above, the level of the heart) • Remember that measurements should be taken bilaterally • Choice of appropriate cuff size for the patient is important to accuracy of measured blood pressure. -

General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

General signs and symptoms of abdominal diseases Dr. Förhécz Zsolt Semmelweis University 3rd Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine, 3rd Year 2018/2019 1st Semester • For descriptive purposes, the abdomen is divided by imaginary lines crossing at the umbilicus, forming the right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower quadrants. • Another system divides the abdomen into nine sections. Terms for three of them are commonly used: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric, or suprapubic Common or Concerning Symptoms • Indigestion or anorexia • Nausea, vomiting, or hematemesis • Abdominal pain • Dysphagia and/or odynophagia • Change in bowel function • Constipation or diarrhea • Jaundice “How is your appetite?” • Anorexia, nausea, vomiting in many gastrointestinal disorders; and – also in pregnancy, – diabetic ketoacidosis, – adrenal insufficiency, – hypercalcemia, – uremia, – liver disease, – emotional states, – adverse drug reactions – Induced but without nausea in anorexia/ bulimia. • Anorexia is a loss or lack of appetite. • Some patients may not actually vomit but raise esophageal or gastric contents in the absence of nausea or retching, called regurgitation. – in esophageal narrowing from stricture or cancer; also with incompetent gastroesophageal sphincter • Ask about any vomitus or regurgitated material and inspect it yourself if possible!!!! – What color is it? – What does the vomitus smell like? – How much has there been? – Ask specifically if it contains any blood and try to determine how much? • Fecal odor – in small bowel obstruction – or gastrocolic fistula • Gastric juice is clear or mucoid. Small amounts of yellowish or greenish bile are common and have no special significance. • Brownish or blackish vomitus with a “coffee- grounds” appearance suggests blood altered by gastric acid. -

The Older Adult 20

CHAPTER The Older Adult 20 Older adults now number more than 25 million people in the United States and are expected to reach 80 million by 2050.1 These seniors will live longer than previous generations: life span at birth is currently 79 years for women and 74 years for men. Those older than 85 years are projected to increase to 5% of the U.S. population within 40 years. Hence, the “demographic im- perative” is to maximize not only the life span but also the “health span” of our older population, so that seniors maintain full function for as long as possible, enjoying rich and active lives in their homes and communities. Clinicians now recognize frailty as one of society’s common myths about aging—more than 95% of Americans older than 65 years live in the commu- nity, and only 5% reside in long-term care facilities.1,2 Over the past 20 years, seniors actually have become more active and less disabled. These changes call for new goals for clinical care—“an informed activated patient inter- acting with a prepared proactive team, resulting in high quality satisfying en- counters and improved outcomes”3—and a distinct set of clinical attitudes and skills. CHAPTER 20 I THE OLDER ADULT 839 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY Assessing the older adult presents special opportunities and special challenges. Many of these are quite different from the disease-oriented approach of his- tory taking and physical examination for younger patients: the focus on healthy or “successful” aging; the need to understand and mobilize family, social, and community supports; the importance of skills directed to func- tional assessment, “the sixth vital sign”; and the opportunities for promoting the older adult’s long-term health and safety. -

Bates' Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

Lynn S. Bickley, MD, FACP Clinical Professor of Internal Medicine School of Medicine University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Peter G. Szilagyi, MD, MPH Professor of Pediatrics Chief, Division of General Pediatrics University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York Acquisitions Editor: Elizabeth Nieginski/Susan Rhyner Product Manager: Annette Ferran Editorial Assistant: Ashley Fischer Design Coordinator: Joan Wendt Art Director, Illustration: Brett MacNaughton Manufacturing Coordinator: Karin Duffield Indexer: Angie Allen Prepress Vendor: Aptara, Inc. 7th Edition Copyright © 2013 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2009 by Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2007, 2004, 2000 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 1995, 1991 by J. B. Lippincott Company. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appear- ing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at Two Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia PA 19103, via email at [email protected] or via website at lww.com (products and services). 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bickley, Lynn S. Bates’ pocket guide to physical examination and history taking / Lynn S. -

PERFORATED PEPTIC ULCER. Patient Usually Experiences

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.12.134.470 on 1 December 1936. Downloaded from 470 POST-GRADUATE MEDICAL JOURNAL December, 1936 PERFORATED PEPTIC ULCER. By RONALD W. RAVEN, F.R.C.S. (Assistant Surgeon to T'he French Hospital, Assistant Surgeon to The Gordon Hospital for Rectal Diseases and Swrgical Registrar to The Royal Cancer Hospital.) INTRODUCTION. Peptic ulceration is a crippling disease judged from the stand-point of morbidity, and is also dangerous to life on account of serious complications, such as haemorrhage or perforation which may supervene during the course of the disease. These complications may occur in any patient and there are no criteria which will indicate whether or not an ulcer will bleed or perforate. When the treatment of peptic ulceration is under review it must be remembered that from 20 to 30 per cent. of these ulcers perforate. In a large series of cases I found that the incidence of perforation was 27 per cent. It is thus essential that patients suffering with peptic ulcer should be kept under continuous careful observation. Unfortunately, however, a small percentage of patients give no previous history of the peptic ulcer syndrome and perforation of the ulcer is the first indication of its presence. Recently, when considering the role of surgery in the treatment of chronic peptic ulcer, Joll stated that there has been a rise in the incidence of perforation as a complication of peptic ulcer since medical treatment has become systematized in the treatment of this disease. It must also be remembered that medical treat- Protected by copyright. -

Review of Systems

code: GF004 REVIEW OF SYSTEMS First Name Middle Name / MI Last Name Check the box if you are currently experiencing any of the following : General Skin Respiratory Arthritis/Rheumatism Abnormal Pigmentation Any Lung Troubles Back Pain (recurrent) Boils Asthma or Wheezing Bone Fracture Brittle Nails Bronchitis Cancer Dry Skin Chronic or Frequent Cough Diabetes Eczema Difficulty Breathing Foot Pain Frequent infections Pleurisy or Pneumonia Gout Hair/Nail changes Spitting up Blood Headaches/Migraines Hives Trouble Breathing Joint Injury Itching URI (Cold) Now Memory Loss Jaundice None Muscle Weakness Psoriasis Numbness/Tingling Rash Obesity Skin Disease Osteoporosis None Rheumatic Fever Weight Gain/Loss None Cardiovascular Gastrointestinal Eyes - Ears - Nose - Throat/Mouth Awakening in the night smothering Abdominal Pain Blurring Chest Pain or Angina Appetite Changes Double Vision Congestive Heart Failure Black Stools Eye Disease or Injury Cyanosis (blue skin) Bleeding with Bowel Movements Eye Pain/Discharge Difficulty walking two blocks Blood in Vomit Glasses Edema/Swelling of Hands, Feet or Ankles Chrohn’s Disease/Colitis Glaucoma Heart Attacks Constipation Itchy Eyes Heart Murmur Cramping or pain in the Abdomen Vision changes Heart Trouble Difficulty Swallowing Ear Disease High Blood Pressure Diverticulosis Ear Infections Irregular Heartbeat Frequent Diarrhea Ears ringing Pain in legs Gallbladder Disease Hearing problems Palpitations Gas/Bloating Impaired Hearing Poor Circulation Heartburn or Indigestion Chronic Sinus Trouble Shortness -

Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Ascites

INVITED REVIEW Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Ascites ÃMatthew J. Giefer, ÃKaren F. Murray, and yRichard B. Colletti ABSTRACT pressure of mesenteric capillaries is normally about 20 mmHg. The pediatric population has a number of unique considerations related to Intestinal lymph drains from regional lymphatics and ultimately the diagnosis and treatment of ascites. This review summarizes the physio- combines with hepatic lymph in the thoracic duct. Unlike the logic mechanisms for cirrhotic and noncirrhotic ascites and provides a sinusoidal endothelium, the mesenteric capillary membrane is comprehensive list of reported etiologies stratified by the patient’s age. relatively impermeable to albumin; the concentration of protein Characteristic findings on physical examination, diagnostic imaging, and in mesenteric lymph is only about one-fifth that of plasma, so there abdominal paracentesis are also reviewed, with particular attention to those is a significant osmotic gradient that promotes the return of inter- aspects that are unique to children. Medical and surgical treatments of stitial fluid into the capillary. In the normal adult, the flow of lymph ascites are discussed. Both prompt diagnosis and appropriate management of in the thoracic duct is about 800 to 1000 mL/day (3,4). ascites are required to avoid associated morbidity and mortality. Ascites from portal hypertension occurs when hydrostatic Key Words: diagnosis, etiology, management, pathophysiology, pediatric and osmotic pressures within hepatic and mesenteric capillaries ascites produce a net transfer of fluid from blood vessels to lymphatic vessels at a rate that exceeds the drainage capacity of the lym- (JPGN 2011;52: 503–513) phatics. It is not known whether ascitic fluid is formed predomi- nantly in the liver or in the mesentery. -

Review of Systems – Return Visit Have You Had Any Problems Related to the Following Symptoms in the Past Month? Circle Yes Or No

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS – RETURN VISIT HAVE YOU HAD ANY PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE FOLLOWING SYMPTOMS IN THE PAST MONTH? CIRCLE YES OR NO Today’s Date: ______________ Name: _______________________________ Date of Birth: __________________ GENERAL GENITOURINARY Fatigue Y N Blood in Urine Y N Fever / Chills Y N Menstrual Irregularity Y N Night Sweats Y N Painful Menstrual Cycle Y N Weight Gain Y N Vaginal Discharge Y N Weight Loss Y N Vaginal Dryness Y N EYES Vaginal Itching Y N Vision Changes Y N Painful Sex Y N EAR, NOSE, & THROAT SKIN Hearing Loss Y N Hair Loss Y N Runny Nose Y N New Skin Lesions Y N Ringing in Ears Y N Rash Y N Sinus Problem Y N Pigmentation Change Y N Sore Throat Y N NEUROLOGIC BREAST Headache Y N Breast Lump Y N Muscular Weakness Y N Tenderness Y N Tingling or Numbness Y N Nipple Discharge Y N Memory Difficulties Y N CARDIOVASCULAR MUSCULOSKELETAL Chest Pain Y N Back Pain Y N Swelling in Legs Y N Limitation of Motion Y N Palpitations Y N Joint Pain Y N Fainting Y N Muscle Pain Y N Irregular Heart Beat Y N ENDOCRINE RESPIRATORY Cold Intolerance Y N Cough Y N Heat Intolerance Y N Shortness of Breath Y N Excessive Thirst Y N Post Nasal Drip Y N Excessive Amount of Urine Y N Wheezing Y N PSYCHOLOGY GASTROINTESTINAL Difficulty Sleeping Y N Abdominal Pain Y N Depression Y N Constipation Y N Anxiety Y N Diarrhea Y N Suicidal Thoughts Y N Hemorrhoids Y N HEMATOLOGIC / LYMPHATIC Nausea Y N Easy Bruising Y N Vomiting Y N Easy Bleeding Y N GENITOURINARY Swollen Lymph Glands Y N Burning with Urination Y N ALLERGY / IMMUNOLOGY Urinary -

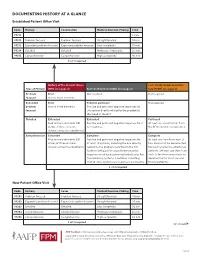

Documenting History at a Glance

DOCUMENTING HISTORY AT A GLANCE Established Patient Office Visit Code History Examination Medical Decision-Making Time 99211 — — — 5 min. 99212 Problem focused Problem focused Straightforward 10 min. 99213 Expanded problem focused Expanded problem focused Low complexity 15 min. 99214 Detailed Detailed Moderate complexity 25 min. 99215 Comprehensive Comprehensive High complexity 40 min. 2 of 3 required History of the Present Illness Past, Family and/or Social His- Type of History (HPI) (see page 2) Review of Systems (ROS) (see page 2) tory (PFSH) (see page 2) Problem Brief Not required Not required focused One to three elements Expanded Brief Problem pertinent Not required problem One to three elements Positive and pertinent negative responses for focused the system directly related to the problem(s) identified in the HPI. Detailed Extended Extended Pertinent Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for 2 At least one specific item from status of three or more to 9 systems. the PFSH must be documented. chronic or inactive conditions) Comprehensive Extended Complete Complete Four or more elements (OR Positive and pertinent negative responses for At least one item from each of status of three or more at least 10 systems, including the one directly two areas must be documented chronic or inactive conditions) related to the problem identified in the HPI. for most services to established Systems with positive or pertinent negative patients. (At least one item from responses must be documented individually. For each of the three areas must be the remaining systems, a notation indicating documented for most services that all other systems are negative is permissible. -

GUIDELINES for WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY and PHYSICALS

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS by Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N, C.S., A.N.P, F.N.P. © 2001 NPCEU Inc. all rights reserved NPCEU INC. PO Box 246 Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-537-9767 - FAX 908-537-6409 www.npceu.com Copyright © 2001 NPCEU Inc. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage, or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission of the publisher: NPCEU, Inc. PO Box 246, Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-527-9767, Fax 908-527-6409. Bulk Purchase Discounts. For discounts on orders of 20 copies or more, please fax the number above or write the address above. Please state if you are a non-profit organization and the number of copies you are interested in purchasing. 2 GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N., C.S., A.N.P., F.N.P. Written documentation for clinical management of patients within health care settings usually include one or more of the following components. - Problem Statement (Chief Complaint) - Subjective (History) - Objective (Physical Exam/Diagnostics) - Assessment (Diagnoses) - Plan (Orders) - Rationale (Clinical Decision Making) Expertise and quality in clinical write-ups is somewhat of an art-form which develops over time as the student/practitioner gains practice and professional experience. In general, students are encouraged to review patient charts, reading as many H/Ps, progress notes and consult reports, as possible. In so doing, one gains insight into a variety of writing styles and methods of conveying clinical information. -

Abdominal Examination

Abdominal Examination Introduction Wash hands, Introduce self, ask Patients name & DOB & what they like to be called, Explain examination and get consent Expose and lie patient flat General Inspection Patient: stable, pain/discomfort, jaundice, pallor, muscle wasting/cachexia Around bed: vomit bowels etc Hands Flapping tremor (hepatic encephalopathy) Nails: clubbing (cirrhosis, IBD, coeliacs), leukonychia (hypoalbuminemia in liver cirrhosis), koilonychia (iron deficiency anaemia) Palms: palmar erythema (hyperdynamic circulation due to ↑oestrogen levels in liver disease/ pregnancy), Dupuytren’s contracture (familial, liver disease), fingertip capillary glucose monitoring marks (diabetes) Head Eyes: sclera for jaundice (liver disease), conjunctival pallor (anaemia e.g. bleeding, malabsorption), periorbital xanthelasma (hyperlipidaemia in cholestasis) Mouth: glossitis/stomatitis (iron/ B12 deficiency anaemia), aphthous ulcers (IBD), breath odor (e.g. faeculent in obstruction; ketotic in ketoacidosis; alcohol) Neck and torso Ask patient to sit forwards: Neck: feel for lymphadenopathy from behind – especially Virchow's node (gastric malignancy) Back inspection: spider naevi (>5 significant), skin lesions (immunosuppression) Ask patient to relax back: Chest inspection: spider naevi (>5 significant), gynaecomastia, loss of axillary hair (all due to ↑oestrogen levels in liver disease/ pregnancy) Abdomen Inspection: distension (Fluid, Flatus, Fat, Foetus, Faeces), incisional hernias (ask patient to cough), scars, striae (pregnancy,