General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

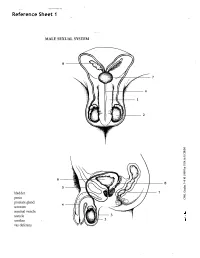

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/Adolescent

Gastroenterology 2016;150:1456–1468 Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/ Adolescent Jeffrey S. Hyams,1,* Carlo Di Lorenzo,2,* Miguel Saps,2 Robert J. Shulman,3 Annamaria Staiano,4 and Miranda van Tilburg5 1Division of Digestive Diseases, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Connecticut Children’sMedicalCenter,Hartford, Connecticut; 2Division of Digestive Diseases, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; 3Baylor College of Medicine, Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas; 4Department of Translational Science, Section of Pediatrics, University of Naples, Federico II, Naples, Italy; and 5Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina Characterization of childhood and adolescent functional Rome III criteria emphasized that there should be “no evi- gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) has evolved during the 2- dence” for organic disease, which may have prompted a decade long Rome process now culminating in Rome IV. The focus on testing.1 In Rome IV, the phrase “no evidence of an era of diagnosing an FGID only when organic disease has inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process been excluded is waning, as we now have evidence to sup- that explain the subject’s symptoms” has been removed port symptom-based diagnosis. In child/adolescent Rome from diagnostic criteria. Instead, we include “after appro- IV, we extend this concept by removing the dictum that priate medical evaluation, the symptoms cannot be attrib- “ ” fi there was no evidence for organic disease in all de ni- uted to another medical condition.” This change permits “ tions and replacing it with after appropriate medical selective or no testing to support a positive diagnosis of an evaluation the symptoms cannot be attributed to another FGID. -

Utility of the Digital Rectal Examination in the Emergency Department: a Review

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1196–1204, 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.015 Clinical Reviews UTILITY OF THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT: A REVIEW Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE*† and Stephen J. Bauer, MD† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and †University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Reprint Address: Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown Veterans Hospital, 820 S Damen Ave., M/C 111, Chicago, IL 60612 , Abstract—Background: The digital rectal examination abdominal pain and acute appendicitis. Stool obtained by (DRE) has been reflexively performed to evaluate common DRE doesn’t seem to increase the false-positive rate of chief complaints in the Emergency Department without FOBTs, and the DRE correlated moderately well with anal knowing its true utility in diagnosis. Objective: Medical lit- manometric measurements in determining anal sphincter erature databases were searched for the most relevant arti- tone. Published by Elsevier Inc. cles pertaining to: the utility of the DRE in evaluating abdominal pain and acute appendicitis, the false-positive , Keywords—digital rectal; utility; review; Emergency rate of fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) from stool obtained Department; evidence-based medicine by DRE or spontaneous passage, and the correlation be- tween DRE and anal manometry in determining anal tone. Discussion: Sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria; there INTRODUCTION were two for abdominal pain, five for appendicitis, six for anal tone, and three for fecal occult blood. -

Observational Study of Children with Aerophagia

Clinical Pediatrics http://cpj.sagepub.com Observational Study of Children With Aerophagia Vera Loening-Baucke and Alexander Swidsinski Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008; 47; 664 originally published online Apr 29, 2008; DOI: 10.1177/0009922808315825 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/47/7/664 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Clinical Pediatrics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cpj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations (this article cites 18 articles hosted on the SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms): http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/47/7/664 Downloaded from http://cpj.sagepub.com at Charite-Universitaet medizin on August 26, 2008 © 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Clinical Pediatrics Volume 47 Number 7 September 2008 664-669 © 2008 Sage Publications Observational Study of Children 10.1177/0009922808315825 http://clp.sagepub.com hosted at With Aerophagia http://online.sagepub.com Vera Loening-Baucke, MD, and Alexander Swidsinski, MD, PhD Aerophagia is a rare disorder in children. The diagnosis is stool and gas. The abdominal X-ray showed gaseous dis- often delayed, especially when it occurs concomitantly tention of the colon in all and of the stomach and small with constipation. The aim of this report is to increase bowel in 8 children. Treatment consisted of educating awareness about aerophagia. This study describes 2 girls parents and children about air sucking and swallowing, and 7 boys, 2 to 10.4 years of age, with functional consti- encouraging the children to stop the excessive air swal- pation and gaseous abdominal distention. -

An Abdominal Tuberculosis Case Mimicking an Abdominal Mass Derya Erdog˘ Ana, Yasemin Tascı¸ Yıldızb, Esin Cengiz Bodurog˘ Luc and Naciye Go¨ Nu¨L Tanırd

Case report 81 An abdominal tuberculosis case mimicking an abdominal mass Derya Erdog˘ ana, Yasemin Tascı¸ Yıldızb, Esin Cengiz Bodurog˘ luc and Naciye Go¨ nu¨l Tanırd Abdominal tuberculosis is rare in childhood. It may be Departments of aPediatric Surgery, bRadiology, cPathology and dPediatric difficult to diagnose as it mimics various disorders. We Infectious Diseases, Dr Sami Ulus Maternity and Children’s Research and Training Hospital, Altındag˘ -Ankara, Turkey present a 12-year-old child with an unusual clinical Correspondence to Derya Erdog˘ an, Dr Sami Ulus Maternity and Children’s presentation who was diagnosed with abdominal Research and Training Hospital, Babu¨r caddesi No. 34 06080, tuberculosis only perioperatively. Ann Pediatr Surg Altındag˘ -Ankara, Turkey Tel: + 90 542 257 5522; fax: + 90 312 317 0353; 9:81–83 c 2013 Annals of Pediatric Surgery. e-mail: [email protected] Annals of Pediatric Surgery 2013, 9:81–83 Received 1 June 2012 accepted 3 January 2013 Keywords: abdominal tuberculosis, child, diagnosis Introduction hyperemia around the umbilicus. A mass with undefined Tuberculosis continues to be an important healthcare borders that filled the whole abdomen was present, and problem, especially in developing countries. Abdominal the paraumblical area was tender on palpation. The tuberculosis is quite rare and can present with different posteroanterior chest and plain abdominal radiographs clinical features in children compared with adults. It can showed nonspecific findings (Fig. 1). Abdominal ultra- be difficult to diagnose as it can mimic various abdominal sonography revealed stage 1 hydronephrosis, minimal diseases. splenomegaly, a multiloculated cystic, and a fine septated mass 51 Â 15 mm in size adjacent to the anterior border of Case report the liver and multiloculated cystic fine septated masses A 12-year-old boy presented with increasing abdominal 51 Â 38 mm in size adjacent to the pancreas inferiorly. -

Osteopathic Approach to the Spleen

Osteopathic approach to the spleen Luc Peeters and Grégoire Lason 1. Introduction the first 3 years to 4 - 6 times the birth size. The position therefore progressively becomes more lateral in place of The spleen is an organ that is all too often neglected in the original epigastric position. The spleen is found pos- the clinic, most likely because conditions of the spleen do tero-latero-superior from the stomach, its arterial supply is not tend to present a defined clinical picture. Furthermore, via the splenic artery and the left gastroepiploic artery it has long been thought that the spleen, like the tonsils, is (Figure 2). The venous drainage is via the splenic vein an organ that is superfluous in the adult. into the portal vein (Figure 2). The spleen is actually the largest lymphoid organ in the body and is implicated within the blood circulation. In the foetus it is an organ involved in haematogenesis while in the adult it produces lymphocytes. The spleen is for the blood what the lymph nodes are for the lymphatic system. The spleen also purifies and filters the blood by removing dead cells and foreign materials out of the circulation The function of red blood cell reserve is also essential for the maintenance of human activity. Osteopaths often identify splenic congestion under the influence of poor diaphragm function. Some of the symptoms that can be associated with dysfunction of the spleen are: Figure 2 – Position and vascularisation of the spleen Anaemia in children Disorders of blood development Gingivitis, painful and bleeding gums Swollen, painful tongue, dysphagia and glossitis Fatigue, hyperirritability and restlessness due to the anaemia Vertigo and tinnitus Frequent colds and infections due to decreased resis- tance Thrombocytosis Tension headaches The spleen is also considered an important organ by the osteopath as it plays a role in the immunity, the reaction of the circulation and oxygen transport during effort as well as in regulation of the blood pressure. -

Editorial Has the Time Come for Cyanoacrylate Injection to Become the Standard-Of-Care for Gastric Varices?

Tropical Gastroenterology 2010;31(3):141–144 Editorial Has the time come for cyanoacrylate injection to become the standard-of-care for gastric varices? Radha K. Dhiman, Narendra Chowdhry, Yogesh K Chawla The prevalence of gastric varices varies between 5% and 33% among patients with portal Department of Hepatology, hypertension with a reported incidence of bleeding of about 25% in 2 years and with a higher Postgraduate Institute of Medical bleeding incidence for fundal varices.1 Risk factors for gastric variceal hemorrhage include the education Research (PGIMER), size of fundal varices [more with large varices (as >10 mm)], Child class (C>B>A), and endoscopic Chandigarh, India presence of variceal red spots (defined as localized reddish mucosal area or spots on the mucosal surface of a varix).2 Gastric varices bleed less commonly as compared to esophageal Correspondence: Dr. Radha K. Dhiman, varices (25% versus 64%, respectively) but they bleed more severely, require more blood E-mail: [email protected] transfusions and are associated with increased mortality.3,4 The approach to optimal treatment for gastric varices remains controversial due to a lack of large, randomized, controlled trials and no clear clinical consensus. The endoscopic treatment modalities depend to a large extent on an accurate categorization of gastric varices. This classification categorizes gastric varices on the basis of their location in the stomach and their relationship with esophageal varices.1,5 Gastroesophageal varices are associated with varices along -

17 Nutrition for Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders 403

84542_ch17.qxd 7/16/09 6:35 PM Page 402 Nutrition for Patients with Upper 17 Gastrointestinal Disorders TRUE FALSE 1 People who have nausea should avoid liquids with meals. 2 Thin liquids, such as clear juices and clear broths, are usually the easiest items to swallow for patients with dysphagia. 3 All patients with dysphagia are given solid foods in pureed form. 4 In people with GERD, the severity of the pain reflects the extent of esophageal damage. 5 High-fat meals may trigger symptoms of GERD. 6 People with esophagitis may benefit from avoiding spicy or acidic foods. 7 Alcohol stimulates gastric acid secretion. 8 A bland diet promotes healing of peptic ulcers. 9 People with dumping syndrome should avoid sweets and sugars. 10 Pernicious anemia is a potential complication of gastric surgery. UPON COMPLETION OF THIS CHAPTER, YOU WILL BE ABLE TO ● Give examples of ways to promote eating in people with anorexia. ● Describe nutrition interventions that may help maximize intake in people who have nausea. ● Compare the three levels of solid food textures included in the National Dysphagia Diet. ● Compare the four liquid consistencies included in the National Dysphagia Diet. ● Plan a menu appropriate for someone with GERD. ● Teach a patient about role of nutrition therapy in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. ● Give examples of nutrition therapy recommendations for people experiencing dumping syndrome. utrition therapy is used in the treatment of many digestive system disorders. For many disorders, diet merely plays a supportive role in alleviating symptoms rather than alter- ing the course of the disease. -

A Pocket Manual of Percussion And

r — TC‘ B - •' ■ C T A POCKET MANUAL OF PERCUSSION | AUSCULTATION FOB PHYSICIANS AND STUDENTS. TRANSLATED FROM THE SECOND GERMAN EDITION J. O. HIRSCHFELDER. San Fbancisco: A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, PUBLISHEBS, BOOKSELLEBS & STATIONEB3. 1873. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, By A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, Iii the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. TRAN jLATOR’S PREFACE. However numerou- the works that have been previously published in the Fi 'lish language on the subject of Per- cussion and Auscultation, there has ever existed a lack of a complete yet concise manual, suitable for the pocket. The translation of this work, which is extensively used in the Universities of Germany, is intended to supply this want, and it is hoped will prove a valuable companion to the careful student and practitioner. J. 0. H. San Francisco, November, 1872. PERCUSSION. For the practice of percussion we employ a pleximeter, or a finger, upon which we strike with a hammer, or a finger, producing a sound, the character of which varies according to the condition of the organs lying underneath the spot percussed. In order to determine the extent of the sound produced, we may imagine the following lines to be drawr n upon the chest: (1) the mammary line, which begins at the union of the inner and middle third of the clavicle, and extends downwards through the nipple; (2) the paraster- nal line, which extends midway between the sternum and nipple ; (3) the axillary line, which extends from the centre of the axilla to the end of the 11th rib. -

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W

Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults NAMIRAH JAMSHED, MD; ZONE-EN LEE, MD; and KEVIN W. OLDEN, MD Washington Hospital Center, Washington, District of Columbia Constipation is traditionally defined as three or fewer bowel movements per week. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low caloric intake, low-fiber diet, low income, low educational level, and taking a large number of medications. Chronic constipa- tion is classified as functional (primary) or secondary. Functional constipation can be divided into normal transit, slow transit, or outlet constipation. Possible causes of secondary chronic constipation include medication use, as well as medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism or irritable bowel syndrome. Frail older patients may present with nonspecific symptoms of constipation, such as delirium, anorexia, and functional decline. The evaluation of constipa- tion includes a history and physical examination to rule out alarm signs and symptoms. These include evidence of bleeding, unintended weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, acute onset constipation in older patients, and rectal prolapse. Patients with one or more alarm signs or symptoms require prompt evaluation. Referral to a subspecialist for additional evaluation and diagnostic testing may be warranted. (Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306. Copyright © 2011 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: onstipation is one of the most of 1,028 young adults, 52 percent defined A patient education common chronic gastrointes- constipation as straining, 44 percent as hard handout on constipation is 1,2 available at http://family tinal disorders in adults. In a stools, 32 percent as infrequent stools, and doctor.org/037.xml. -

Abdominal Pain - Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

ACS/ASE Medical Student Core Curriculum Abdominal Pain - Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease ABDOMINAL PAIN - GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE Epidemiology and Pathophysiology Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most commonly encountered benign foregut disorders. Approximately 20-40% of adults in the United States experience chronic GERD symptoms, and these rates are rising rapidly. GERD is the most common gastrointestinal-related disorder that is managed in outpatient primary care clinics. GERD is defined as a condition which develops when stomach contents reflux into the esophagus causing bothersome symptoms and/or complications. Mechanical failure of the antireflux mechanism is considered the cause of GERD. Mechanical failure can be secondary to functional defects of the lower esophageal sphincter or anatomic defects that result from a hiatal or paraesophageal hernia. These defects can include widening of the diaphragmatic hiatus, disturbance of the angle of His, loss of the gastroesophageal flap valve, displacement of lower esophageal sphincter into the chest, and/or failure of the phrenoesophageal membrane. Symptoms, however, can be accentuated by a variety of factors including dietary habits, eating behaviors, obesity, pregnancy, medications, delayed gastric emptying, altered esophageal mucosal resistance, and/or impaired esophageal clearance. Signs and Symptoms Typical GERD symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, excessive eructation, and epigastric pain. Patients can also present with extra-esophageal symptoms including cough, hoarse voice, sore throat, and/or globus. GERD can present with a wide spectrum of disease severity ranging from mild, intermittent symptoms to severe, daily symptoms with associated esophageal and/or airway damage. For example, severe GERD can contribute to shortness of breath, worsening asthma, and/or recurrent aspiration pneumonia. -

Chronic Upper Abdominal Pain

Gut, 1992, 33, 743-748 743 Chronic upper abdominal pain: site and radiation in various structural and functional disorders and the effect of various foods Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.33.6.743 on 1 June 1992. Downloaded from J Y Kang, HH Tay, R Guan Abstract right or left hypochondrium, periumbilical, Pain site and radiation and the effect ofvarious right or left lumbar, or generalised following the foods were studied prospectively in a consecu- landmarks suggested by French.' The abdomen tive series of patients with chronic upper was divided into nine regions by the intersection abdominal pain. Patients followed for less than of two horizontal and two sagittal planes. The one year were excluded unless peptic ulcer or upper horizontal plane was at a level midway abdominal malignancy had been diagnosed or between the suprasternal notch and the symphy- laparotomy had been carried out. A total of632 sis pubis. The lower plane was at the upper patients .were eligible for the first study and 431 border ofthe iliac crests. The sagittal planes were for the second. Gastric ulcer pain was more vertical lines drawn through points midway likely to be left hypochondrial (17%) compared between the pubis and the anterior superior iliac with pain from duodenal ulcer (4%) or from all spines. Patients with suprapublic and right and other conditions (5%). It was less likely to be left iliac fossa pains were not included in the epigastric (54%) compared with duodenal ulcer present study unless there was concomittant pain (75%). Oesophageal pain was more likely upper abdominal pain.