Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

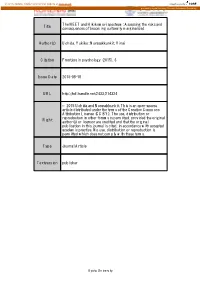

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Language and Culture Chapter 10 ぶんか にほんご 文化・日本語 Culture Bunka/Nihongo

Language and Culture Chapter 10 ぶんか にほんご 文化・日本語 Culture Bunka/Nihongo ぶ ん か 文化 Bunka This section contains a brief overview of some aspects of Japanese culture that you ought to be aware of. If you would like to learn more about Japanese culture, there are a great many books on the subject. This overview is simply meant to help make your life in Japan a little bit easier. The best way to learn proper Japanese manners is to mimic those around you. Etiquette While Eating Like every other country, Japan has specific etiquette for mealtimes. When out to eat with Japanese friends or coworkers it is important to be aware of what is considered rude. いただきます itadakimasu. After sitting down to a meal, and just before beginning to eat, many Japanese will put their hands together, much like how Christians pray, and say itadakimasu. It is not actually a prayer, however, and literally translates as “I humbly receive this.” When out at a restaurant, it is not uncommon for the meals to come out as they are prepared, which may mean that you get your food before your companions, or they will get theirs first. Do not be surprised if they tell you to start eating or begin eating when the food comes. This is just Japanese custom. Generally before digging in you should say something like おさきにすみません osaki ni sumimasen, which means, “excuse me for going first.” They may urge you to eat. If this makes you uncomfortable it is perfectly ok to explain that in your culture you wait until everyone gets their food before eating, but they will not think ill of you for starting without them. -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

Softening Power: Cuteness As Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West

© 2018 Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies Vol. 10, February 2018, pp. 39-55 Master’s and Doctoral Programs in International and Advanced Japanese Studies Iain MACPHERSON & Teri Jane BRYANT Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba Article Softening Power: Cuteness as Organizational Communication Strategy in Japan and the West Iain MACPHERSON MacEwan University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Communication, Assistant Professor Teri Jane BRYANT Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary, Associate Professor Emerita This paper describes the use of cute communications (visual or verbal, and in various media) as an organizational communication strategy prevalent in Japan and emerging in western countries. Insights are offered for the use of such communications and for the understanding/critique thereof. It is first established that cuteness in Japan–kawaii–is chiefly studied as a sociocultural or psychological phenomenon, with too little analysis of its near-omnipresent institutionalization and conveyance as mass media. The following discussion clarifies one reason for this gap in research–the widespread conflation of ʻorganizational communication’ with advertising/branding, notwithstanding the variety of other messaging–public relations, employee communications, public service announcements, political campaigns–conveyed through cuteness by Japanese institutions. It is then argued that what few theorizations exist of organizational kawaii communications overemphasize their negative aspects or potentials, attributing to them both too much iniquity and too much influence. Outside of Japan studies, there is even less up-to-date scholarship on organizational cuteness, critical or otherwise. And there are no such studies at all, whether focused on Japan or elsewhere, that integrate intercultural insights. -

Neets' Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies

NEETs’ Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies NEETS’ CHALLENGE TO JAPAN: CAUSES AND REMEDIES Khondaker Mizanur Rahman Abstract: Based on a questionnaire survey and an interview, with additional sup- port from reviews of literature and archival information, this paper examines the underlying causes of the NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) prob- lem in Japan. Those who responded to the survey were senior-grade students from middle schools, high schools, junior college and university, and a group of opinion leaders, who have no direct experience as freeters or NEETs. Findings from the survey suggest that individual personality attributes such as dislike of and inabil- ity to adapt to things and situations, over-sensitivity etc. which arise from and are exacerbated by unfavorable family, school, social, and workplace related circum- stances, with further negative influences from the economic environment and metamorphic social changes, have given rise to the problem of NEET. The issue has posed a severe challenge to the nation’s labor market, and calls for an immediate solution. The paper offers some inductive and deductive suggestions to eradicate the underlying causes of the problem and arrest its further escalation and prevent recurrence. 1 1. INTRODUCTION: NEET AND THE JAPANESE LABOUR MARKET The term “Not in Employment, Education or Training” (NEET), first used in the analysis of British labor policy in the 1980s to denote people in the age brackets of 16–18 who are “not in employment, education, and train- ing”, was adopted in Japan in 2004, and its meaning and essence were modified to fit into the social and labor market circumstances (Kosugi 2005a: 7–8; Wikipedia 2005, Internet). -

1 Japanese and Brazilian Female

JAPANESE AND BRAZILIAN FEMALE TEACHERS’ DIRECTIVE/COMPLIANCE- GAINING STRATEGIES: A LANGUAGE SOCIALIZATION PERSPECTIVE By MUTSUO NAKAMURA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 1 © 2014 Mutsuo Nakamura 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Dr. Boxer for being a great mentor, supporting me during the process of writing this academic work. I also thank Dr. Coady, Dr. Golombek, Dr. Lord, and Dr. McLaughlin for being on my committee. I thank Dr. LoCastro for the support she gave me in many ways. I would like to thank my UF friends who have supported me in the process: Alejandro P., Amanda H., Ana María D., Antonio D., Antonio T., Asmeret M., Belle L., Carolina G., David V., Dawn F., Elli S., Eugenio, P., Fabiola D., Jimmy H., Juan C., Juan V., Machel M., Maria M., Martin M., Mónica A., Priyankoo S., Rosana R., Rui C., Yuko F., and many more friends I met in the Gatorland. I thank my friends in Japan and in Mexico for their support: Cecilia A., Cristina Y., Edna T., Esteban G., Fukuhara-san, Irma-san, Izumi-san, Rosario P., and other friends. I also thank my deceased Mexican and Japanese mentors: François L., Víctor F., and Tobita-sensei. I thank Hong Ling for accompanying me in the process of writing this academic work. Finally, I thank my parents for their support and understanding. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life

From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life Mark Patrick McGuire A Thesis In The Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada April 2013 Mark Patrick McGuire, 2013 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mark Patrick McGuire Entitled: From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. V. Penhune External Examiner Dr. B. Ambros External to Program Dr. S. Ikeda Examiner Dr. N. Joseph Examiner Dr. M. Penny Thesis Supervisor Dr. M. Desjardins Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dr. S. Hatley, Graduate Program Director April 15, 2013 Dr. B. Lewis, Dean, Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT From the City to the Mountain and Back Again: Situating Contemporary Shugendô in Japanese Social and Religious Life Mark Patrick McGuire, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2013 This thesis examines mountain ascetic training practices in Japan known as Shugendô (The Way to Acquire Power) from the 1980s to the present. Focus is given to the dynamic interplay between two complementary movements: 1) the creative process whereby charismatic, media-savvy priests in the Kii Peninsula (south of Kyoto) have re-invented traditional practices and training spaces to attract and satisfy the needs of diverse urban lay practitioners, and 2) the myriad ways diverse urban ascetic householders integrate lessons learned from mountain austerities in their daily lives in Tokyo and Osaka. -

The Orientalist Gaze: a Feminist Analysis of Japanese-U.S

REFLECTING [ON] THE ORIENTALIST GAZE: A FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF JAPANESE-U.S. GIS INTIMACY IN POSTWAR JAPAN AND CONTEMPORARY OKINAWA BY Ayako Mizumura Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________ Joane Nagel, Chair _____________________________ Shirley A. Hill _____________________________ Mehrangiz Najafizadeh _____________________________ Sherrie Tucker _____________________________ Bill Tsutsui _____________________________ Elaine Gerbert Date Defended: __April 28, 2009__ The Dissertation Committee for Ayako Mizumura certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REFLECTING [ON] THE ORIENTALIST GAZE: A FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF JAPANESE-U.S. GIS INTIMACY IN POSTWAR JAPAN AND CONTEMPORARY OKINAWA Committee: _____________________________ Joane Nagel, Chair _____________________________ Shirley A. Hill _____________________________ Mehrangiz Najafizadeh _____________________________ Sherrie Tucker _____________________________ Bill Tsutsui _____________________________ Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: __April 28, 2009__ ii ABSTRACT Ayako Mizumura, Ph.D. Department of Sociology, Summer 2009 University of Kansas Reflecting [on] the Orientalist Gaze: A Feminist Analysis of Japanese Women- U.S. GIs Intimacy in Postwar Japan and Contemporary Okinawa This project explores experiences of two generations of Japanese women, “war brides,” who married American -

The Spiritual Quest of Uchimura Kanzō by Christopher A

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Summer 8-15-2017 Native Roots and Foreign Grafts: The pirS itual Quest of Uchimura Kanzō Christopher Andrew Born Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Born, Christopher Andrew, "Native Roots and Foreign Grafts: Thep S iritual Quest of Uchimura Kanzō" (2017). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1247. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1247 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Marvin H. Marcus, Chair Rebecca Copeland Jamie Lynn Newhard David Schmitt Lori Watt Native Roots and Foreign Grafts: The Spiritual Quest of Uchimura Kanzō by Christopher A. Born A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Uchi-Soto (Inside-Outside): Language and Culture In

UCHI-SOTO (INSIDE-OUTSIDE): LANGUAGE AND CULTURE IN CONTEXT FOR THE JAPANESE AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE (JFL) LEARNER ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Teaching International Languages ____________ by © Jamie Louise Goekler 2010 Fall 2010 UCHI-SOTO (INSIDE-OUTSIDE): LANGUAGE AND CULTURE IN CONTEXT FOR THE JAPANESE AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE (JFL) LEARNER A Thesis by Jamie Louise Goekler Fall 2010 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: Katie Milo, Ed.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Hilda Hernández, Ph.D. Hilda Hernández, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Kimihiko Nomura, Ed.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION To all of us who have become someone else in order to communicate with someone from somewhere else while still remaining true to ourselves. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I dedicate this Japanese as a Foreign Language research to patient, dedicated and loving mentors— my family and extended family, teachers, professors, students, and friends from around the globe, all of whom have stood beside me throughout my years as a student and a teacher. I’d especially like to thank Dr. Hilda Hernández, my committee chair and academic advisor, to whom I will always be grateful and indebted, and Dr. Kimihiko Nomura for his unfailing support. In addition, I would like to thank my favorite school teacher and mentor, Diane Lundblad and college Spanish professor, Martha Racine.