Hikikomori As a Gendered Issue Analysis on the Discourse of Acute Social Withdrawal in Contemporary Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

READERS' FORUM Cram Schools in Japan

READERS’ FORUM Cram Schools in Japan: The Need for Research been the subject of considerable amounts of re- Robert J. Lowe search. Studies have been carried out in these con- Rikkyo University texts regarding educational policy (see Hashimoto, 2009; Yonezawa, Akiba, & Hiouchi, 2009), teaching methodologies (see Gorsuch, 2001; Nishino & Wata- The private juku (cram school) industry is an enormously prof- nabe, 2008), classroom policies on language use itable and influential area of education in Japan, including in the specific field of English language teaching (ELT). However, (see Hashimoto, 2013; Yphantides, 2013), teaching while much research has been carried out in other areas of ELT materials (see Yamanaka, 2006; Mineshima, 2008; in Japan, juku have largely escaped the attention of research- Sano, Iida, & Harvey, 2009), teacher and student ers. This paper attempts to argue the need for more research perspectives (see O’Donnell, 2008; McKenzie, 2008; into English language education as it is practiced in juku. The article first situates juku within the Japanese education sys- Rudolph and Igarashi, 2012), teacher identities (see tem, and then illustrates the extent to which juku have been Butler, 2007; Nagatomo, 2012) and many other under-researched when compared to other ELT contexts in areas. As a result, much is known about English Japan. The author advocates the need for more research into education in these settings, providing views on each ELT to be carried out in juku, and finally suggests some areas context at different magnifications, from the overall into which this research could be conducted. structure of the institution to the details of class- 学習塾産業は大きなビジネスであり、日本の英語教育に大きな影響を room teaching and interaction. -

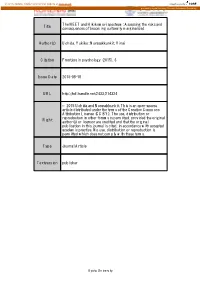

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Problem Gambling: How Japan Could Actually Become the Next Las Vegas

[Type here] PROBLEM GAMBLING: HOW JAPAN COULD ACTUALLY BECOME THE NEXT LAS VEGAS Jennifer Roberts and Ted Johnson INTRODUCTION Although with each passing day it appears less likely that integrated resorts with legalized gaming will become part of the Tokyo landscape in time for the city’s hosting of the summer Olympics in 20201, there is still substantial international interest in whether Japan will implement a regulatory system to oversee casino-style gaming. In 2001, Macau opened its doors for outside companies to conduct casino gaming operations as part of its modernized gaming regulatory system.2 At that time, it was believed that Macau would become the next Las Vegas.3 Just a few years after the new resorts opened, many operated by Las Vegas casino company powerhouses, Macau surpassed Las Vegas as the “gambling center” at one point.4 With tighter restrictions and crackdowns on corruption, Macau has since experienced declines in gaming revenue.5 When other countries across Asia have either contemplated or adopted gaming regulatory systems, it is often believed that they could become the 1 See 2020 Host City Election, OLYMPIC.ORG, http://www.olympic.org/2020-host- city-election (last visited Oct. 25, 2015). 2 Macau Gaming Summary, UNLV CTR. FOR GAMING RES., http://gaming. unlv.edu/ abstract/macau.html (last visited Oct. 25, 2015). 3 David Lung, Introduction: The Future of Macao’s Past, in THE CONSERVATION OF URBAN HERITAGE: MACAO VISION – INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE xiii, xiii (The Cultural Inst. of the Macao S. A. R. Gov’t: Studies, Research & Publ’ns Div. 2002), http://www.macauheritage.net/en/knowledge/vision/vision_xxi.pdf (noting, in 2002, of outside investment as possibly creating a “Las Vegas of the East”). -

Asia Program Special Report

JULY 2008 AsiaSPECIAL Program REPORT No. 141 Japan’s Declining Population: Clearly a LEONARD SCHOPPA Japan’s Declining Population: The Problem, But What’s the Solution? Perspective of Japanese Women on the “Problem” and the “Solutions” EDITED BY MARK MOHR PAGE 6 ROBIN LEBLANC Japan’s Low Fertility: What Have Men ABSTRACT Got To Do With It? In this Special Report, Leonard Schoppa of the University of Virginia notes PAGE 11 the lack of an organized female “voice” to press for better job conditions which would KEIKO YAMANAKA make having both a career and children easier. Robin LeBlanc of Washington and Lee Immigration, Population and University describes the pressures facing Japanese men, which have led to their postpon- Multiculturalism in Japan PAGE 19 ing marriage at a higher rate than women, while Keiko Yamanaka of the University of JENNIFER ROBERTSON California, Berkeley, reluctantly concludes that Japan is not seriously considering immigration Science Fiction as Domestic Policy in as an option to counteract its declining population. Jennifer Robertson of the University Japan: Humanoid Robots, Posthumans, of Michigan, Ann Arbor, focuses on a uniquely Japanese technological solution to possibly and Innovation 25 PAGE 29 resolve the problem of a declining population: robots. INTRODUCTION MARK MOHR apan’s population is shrinking. Its fertility total exactly one. Whether this remaining citizen rate is an alarmingly low 1.3; 2.1 is the rate will be male or female, the study did not say. Jnecessary for population replacement. At the Japan is thus facing a major demographic cri- current fertility rate, Japan’s population, which sis: not enough workers to support an increasingly currently totals 127.7 million, will decrease by aging population; not enough babies to replace over 40 million by 2055. -

Those Restless Little Boats on the Uneasiness of Japanese Power-Boat Gamblers

Course No. 3507/3508 Contemporary Japanese Culture and Society Lecture No. 15 Gambling ギャンブル・賭博 GAMBLING … a national obession. Gambling fascinates, because it is a dramatized model of life. As people make their way through life, they have to make countless decisions, big and small, life-changing and trivial. In gambling, those decisions are reduced to a single type – an attempt to predict the outcome of an event. Real-life decisions often have no clear outcome; few that can clearly be called right or wrong, many that fall in the grey zone where the outcome is unclear, unimportant, or unknown. Gambling decisions have a clear outcome in success or failure: it is a black and white world where the grey of everyday life is left behind. As a simplified and dramatized model of life, gambling fascinates the social scientist as well as the gambler himself. Can the decisions made by the gambler offer us a short-cut to understanding the character of the individual, and perhaps even the collective? Gambling by its nature generates concrete, quantitative data. Do people reveal their inner character through their gambling behavior, or are they different people when gambling? In this paper I will consider these issues in relation to gambling on powerboat races (kyōtei) in Japan. Part 1: Institutional framework Gambling is supposed to be illegal in Japan, under article 23 of the Penal Code, which prescribes up to three years with hard labor for any “habitual gambler,” and three months to five years with hard labor for anyone running a gambling establishment. Gambling is unambiguously defined as both immoral and illegal. -

Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government

Papers on the Local Governance System and its Implementation in Selected Fields in Japan No.16 Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government Yoshinori ISHIKAWA Executive director, JKA Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) Except where permitted by the Copyright Law for “personal use” or “quotation” purposes, no part of this booklet may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission. Any quotation from this booklet requires indication of the source. Contact Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) (The International Information Division) Sogo Hanzomon Building 1-7 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 Japan TEL: 03-5213-1724 FAX: 03-5213-1742 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.clair.or.jp/ Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677 Japan TEL: 03-6439-6333 FAX: 03-6439-6010 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www3.grips.ac.jp/~coslog/ Foreword The Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) and the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) have been working since FY 2005 on a “Project on the overseas dissemination of information on the local governance system of Japan and its operation”. On the basis of the recognition that the dissemination to overseas countries of information on the Japanese local governance system and its operation was insufficient, the objective of this project was defined as the pursuit of comparative studies on local governance by means of compiling in foreign languages materials on the Japanese local governance system and its implementation as well as by accumulating literature and reference materials on local governance in Japan and foreign countries. -

The ECHO Volume 56 Number 2 Volume 56 Number 2

February 2017 The ECHO Volume 56 Number 2 Volume 56 Number 2 MOUNTAIN VIEW BUDDHIST TEMPLE February Highlights Our Big Win We have Senior Activities at it. And, I sincerely hope that 2/5 Sun Shotsuki Hoyo Service our Temple every Thursday morn- someone will hit a jackpot during 11:00 am ing. About 30 people come each the next Reno trip and make a Japanese Language week to do line dancing or crafts, generous donation to our Temple! Service play cards or hanafuda (a Japanese America has three big cities card game), or sing Japanese songs full of casinos: Las Vegas, Reno and 2/6 Mon, 7:00 pm together. Everyone has a very Atlantic City. The U.S. has been Tannisho Study Class fruitful time in their own way. the casino capital of the world. 2/8 Wed, 7:30 pm Early in my assignment here, I Vegas especially not only has gam- Temple Board Meeting joined the line dancing group. I bling, but lots of wonderful enter- really enjoy stepping to the music tainment. This is why it attracts 2/11 Sat, 5:00 pm together and am grateful to have a tourists from all over the world YBA Spaghetti Dinner & way to overcome my physical inac- and is full of life all the time. Bingo By Rev. Yushi Mukojima tivity. In contrast, gambling in Japan 2/12 Sun, 10:00 am The Seniors who come to the me, “Sensei, I couldn’t win even consists of pachinko and four types Nirvana Day & Pet Temple are very active and enjoy though I said the Nembutsu!” He Memorial Service their life full of smiles in harmony. -

Dansō, Gender, and Emotion Work in a Tokyo Escort Service

WALK LIKE A MAN, TALK LIKE A MAN: DANSŌ, GENDER, AND EMOTION WORK IN A TOKYO ESCORT SERVICE A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 MARTA FANASCA SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ...................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration and Copyright Statement .................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 Significance and aims of the research .................................................................................. 12 Outline of the thesis ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1 Masculinity in Japan ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2 Dansō and gender definition -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

Neets' Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies

NEETs’ Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies NEETS’ CHALLENGE TO JAPAN: CAUSES AND REMEDIES Khondaker Mizanur Rahman Abstract: Based on a questionnaire survey and an interview, with additional sup- port from reviews of literature and archival information, this paper examines the underlying causes of the NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) prob- lem in Japan. Those who responded to the survey were senior-grade students from middle schools, high schools, junior college and university, and a group of opinion leaders, who have no direct experience as freeters or NEETs. Findings from the survey suggest that individual personality attributes such as dislike of and inabil- ity to adapt to things and situations, over-sensitivity etc. which arise from and are exacerbated by unfavorable family, school, social, and workplace related circum- stances, with further negative influences from the economic environment and metamorphic social changes, have given rise to the problem of NEET. The issue has posed a severe challenge to the nation’s labor market, and calls for an immediate solution. The paper offers some inductive and deductive suggestions to eradicate the underlying causes of the problem and arrest its further escalation and prevent recurrence. 1 1. INTRODUCTION: NEET AND THE JAPANESE LABOUR MARKET The term “Not in Employment, Education or Training” (NEET), first used in the analysis of British labor policy in the 1980s to denote people in the age brackets of 16–18 who are “not in employment, education, and train- ing”, was adopted in Japan in 2004, and its meaning and essence were modified to fit into the social and labor market circumstances (Kosugi 2005a: 7–8; Wikipedia 2005, Internet).