Hikikomori- a Generation in Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

Methods to Estimate the Structure and Size of the “Neet” Youth

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Economics and Finance 32 ( 2015 ) 119 – 124 Emerging Markets Queries in Finance and Business Methods to estimate the structure and size of the "neet" youth Mariana Bălan* The Institute of National Economy, Casa Academiei Române, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Bucharest, 050711, Romania Abstract In 2013, in EU-27, were employed only 46.1% of the young people aged 15-29 years, this being the lowest figure ever recorded by Eurostat statistics. In Romania, in the same year, were employed only 40.8% of the young people aged 15-29 years. According to Eurostat, in 2013, in Europe, over 8 million young people aged 15-29 were excluded from the labour market and the education system. This boosted the rate of NEET population, aged 15-29, from the 13% level recorded in 2008 to 15.9% in 2013, with significant variations between the Member States: less than 7.5% in the Netherlands, more than 20% in Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, Greece and Spain. In Romania, under the impact of the financial crisis, the rate of NEET population increased from 13.2% in 2008 to 19.1% in 2011 and 19.6% in 2013. This paper presents a brief analysis of the labour market in the European Union and the particularities of the youth labour market in Romania. It analyses, for the pre-crisis period and under its impact, the structure, the education and the gender composition of NEET groups. Some stochastic methods are used to estimate the structure and size of the NEET rates and of the youth unemployment rate in Romania. -

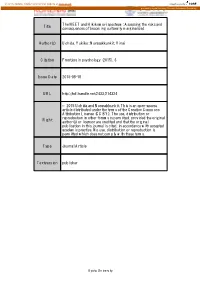

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Youth in Greece

AD HOC REPORT Youth in Greece Produced at the request of the Greek government, in the context of its integrated strategy for youth Youth in Greece European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions When citing this report, please use the following wording: Eurofound (2018), Youth in Greece, Eurofound, Dublin. Author: Stavroula Demetriades (Eurofound) Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union Print: ISBN: 978-92-897-1634-5 doi:10.2806/153325 TJ-01-18-182-EN-C PDF: ISBN: 978-92-897-1635-2 doi:10.2806/879954 TJ-01-18-182-EN-N © European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2018 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Images: © Eurofound 2017, Peter Cernoch For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the Eurofound copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) is a tripartite European Union Agency, whose role is to provide knowledge in the area of social, employment and work-related policies. Eurofound was established in 1975 by Council Regulation (EEC) No. 1365/75 to contribute to the planning and design of better living and working conditions in Europe. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions Telephone: (+353 1) 204 31 00 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eurofound.europa.eu Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number*: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 *Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. -

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: an Extension of Graduate Thesis

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: An Extension of Graduate Thesis 経済学研究科経済学専攻博士後期課程在学 荒 木 悠 Haruka Araki Table of Contents: Ⅰ.Introduction Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun sets into the Lost Decade A.General Overview Ⅲ.Major Causes of the Bubble Burst A.Financial Deregulation B.Asset Price Deflation C.Non-Performing Loans D.Investment Ⅳ.Theoretical Background and Insight into the Japanese Experience Ⅴ.Conclusion Ⅰ.Introduction The “Lost Decade” – the country known as of the rising sun was not brimming with rays of hope during the 1990’s. Japan’s economy plummeted into stagnation after the bubble burst in 1991, entering into periods of near zero economic growth; an alarming change from its average 4.0 percent growth in the 1980’s. The amount of literature on the causes of the Japanese economic bubble burst is vast and its content ample, ranging from asset-price deflation, financial deregulation, deficient banking system, failing macroeconomic policies, etc. This paper, an overview of this writer’s graduate thesis, re-examines the post-bubble economy of Japan, an endeavor supported by additional past works coupled with original data analysis, beginning with a general overview of the Japanese economy during the bubble compared to after the burst. Several theories carried by some scholars were chosen as this paper attempts to relate the theory to the actuality of the Japanese experience during the lost decade. - 31 - Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun to the Lost Decade A. General Overview The so-called Japanese “bubble economy” marked high economic growth. The 1973 period of high growth illustrated an average real growth rate of GDP/capita of close to 10 percent. -

What Does Neets Mean and Why Is the Concept So Easily

What does NEETs mean and why is the concept so easily misinterpreted? Technical Brief No.1 Introduction The share of youth which are neither in employment nor in education or training in the youth population (the so-called “NEET rate”) is a relatively new indicator, but one that is given increasing importance by international organizations and the media. The popularity of the “NEET” concept is associated with its assumed potential to address a broad array of vulnerabilities among youth, touching on issues of unemployment, early school leaving and labour market discouragement. These are all issues that warrant greater attention as young people continue to feel the aftermath of the economic crisis, particularly in advanced economies. From a little known indicator aimed at focusing attention on the issue of school drop-out among teenagers in the early 2000s, the indicator has gained enough weight to be proposed as the sole youth-specific target for the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 8 to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. Within the Goal, youth are identified in two proposed targets: (i) by 2030 achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value, and (ii) by 2020 substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET). It is the author’s opinion that the NEET rate is an indicator that is widely misunderstood and therefore misinterpreted. The critique which follows is intended to point out some misconceptions so that the indicator can be framed around what it really measures, rather than what it does not. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Asia Program Special Report

JULY 2008 AsiaSPECIAL Program REPORT No. 141 Japan’s Declining Population: Clearly a LEONARD SCHOPPA Japan’s Declining Population: The Problem, But What’s the Solution? Perspective of Japanese Women on the “Problem” and the “Solutions” EDITED BY MARK MOHR PAGE 6 ROBIN LEBLANC Japan’s Low Fertility: What Have Men ABSTRACT Got To Do With It? In this Special Report, Leonard Schoppa of the University of Virginia notes PAGE 11 the lack of an organized female “voice” to press for better job conditions which would KEIKO YAMANAKA make having both a career and children easier. Robin LeBlanc of Washington and Lee Immigration, Population and University describes the pressures facing Japanese men, which have led to their postpon- Multiculturalism in Japan PAGE 19 ing marriage at a higher rate than women, while Keiko Yamanaka of the University of JENNIFER ROBERTSON California, Berkeley, reluctantly concludes that Japan is not seriously considering immigration Science Fiction as Domestic Policy in as an option to counteract its declining population. Jennifer Robertson of the University Japan: Humanoid Robots, Posthumans, of Michigan, Ann Arbor, focuses on a uniquely Japanese technological solution to possibly and Innovation 25 PAGE 29 resolve the problem of a declining population: robots. INTRODUCTION MARK MOHR apan’s population is shrinking. Its fertility total exactly one. Whether this remaining citizen rate is an alarmingly low 1.3; 2.1 is the rate will be male or female, the study did not say. Jnecessary for population replacement. At the Japan is thus facing a major demographic cri- current fertility rate, Japan’s population, which sis: not enough workers to support an increasingly currently totals 127.7 million, will decrease by aging population; not enough babies to replace over 40 million by 2055. -

Dansō, Gender, and Emotion Work in a Tokyo Escort Service

WALK LIKE A MAN, TALK LIKE A MAN: DANSŌ, GENDER, AND EMOTION WORK IN A TOKYO ESCORT SERVICE A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 MARTA FANASCA SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ...................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration and Copyright Statement .................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 Significance and aims of the research .................................................................................. 12 Outline of the thesis ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1 Masculinity in Japan ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2 Dansō and gender definition -

Japan in the Reiwa Era – New Opportunities for International Investors

1 Japan in the Reiwa Era – New Opportunities for International Investors Keynote Address to Financial Times Live/Nikkei Briefing on “Unlocking the Potential of Japanese Equities: Capturing the value of the Nikkei 225” June 25, 2019, New York Paul Sheard M-RCBG Senior Fellow Harvard Kennedy School [email protected] Thank you very much for that kind introduction. It is a pleasure and an honor to be able to give some keynote remarks to set the stage for the distinguished panel to follow. I should start by noting that I am an economist and long-term Japan-watcher, not an equity strategist or someone who gives investment advice. I am going to focus on the big picture. Japan, a $5 trillion economy, does not get as much attention as it deserves. It is still the third largest economy in the world, with 5.9% of global GDP, using market exchange rates, or the fourth largest if measured in PPP (purchasing power parity) terms, with a share of 4.1%. Japan seriously punches below its weight – if it were a stock, it would be a value stock. I am going to tell you three things that worry me about Japan and three things that don’t. But before doing that, given that the title of the address mentions the Reiwa era, it is worth reflecting for a moment on Japan’s experience in the preceding Heisei era, which started on January 8, 1989 and ended on April 30, 2019. A lot happened and Japan changed a lot in those thirty years.