Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

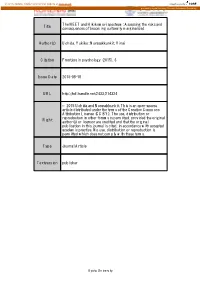

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

Dansō, Gender, and Emotion Work in a Tokyo Escort Service

WALK LIKE A MAN, TALK LIKE A MAN: DANSŌ, GENDER, AND EMOTION WORK IN A TOKYO ESCORT SERVICE A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 MARTA FANASCA SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ...................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration and Copyright Statement .................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 Significance and aims of the research .................................................................................. 12 Outline of the thesis ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1 Masculinity in Japan ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2 Dansō and gender definition -

Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know

1 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian Sophia University Tokyo, Japan 2 Contents About this Book ......................................................................................... 4 The Editor ................................................................................................ 5 Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know ................................................. 6 Contributors of This Book ............................................................................ 94 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 96 Further Reading on Japanese Management .................................................... 102 3 About this Book This book is the result of one of my “Management in Japan” classes held at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Sophia University in Tokyo. Students wrote this dictionary entries, I edited and updated them. The document is now available as a free e-book at my homepage www.haghirian.com. We hope that this book improves understanding of Japanese management and serves as inspiration for anyone interested in the subject. Questions and comments can be sent to [email protected]. Please inform the editor if you plan to quote parts of the book. Japanese Business Concepts You Should Know Edited by Parissa Haghirian First edition, Tokyo, October 2019 4 The Editor Parissa Haghirian is Professor of International Management at Sophia University in Tokyo. She lives and works in Japan since 2004 -

Neets' Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies

NEETs’ Challenge to Japan: Causes and Remedies NEETS’ CHALLENGE TO JAPAN: CAUSES AND REMEDIES Khondaker Mizanur Rahman Abstract: Based on a questionnaire survey and an interview, with additional sup- port from reviews of literature and archival information, this paper examines the underlying causes of the NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) prob- lem in Japan. Those who responded to the survey were senior-grade students from middle schools, high schools, junior college and university, and a group of opinion leaders, who have no direct experience as freeters or NEETs. Findings from the survey suggest that individual personality attributes such as dislike of and inabil- ity to adapt to things and situations, over-sensitivity etc. which arise from and are exacerbated by unfavorable family, school, social, and workplace related circum- stances, with further negative influences from the economic environment and metamorphic social changes, have given rise to the problem of NEET. The issue has posed a severe challenge to the nation’s labor market, and calls for an immediate solution. The paper offers some inductive and deductive suggestions to eradicate the underlying causes of the problem and arrest its further escalation and prevent recurrence. 1 1. INTRODUCTION: NEET AND THE JAPANESE LABOUR MARKET The term “Not in Employment, Education or Training” (NEET), first used in the analysis of British labor policy in the 1980s to denote people in the age brackets of 16–18 who are “not in employment, education, and train- ing”, was adopted in Japan in 2004, and its meaning and essence were modified to fit into the social and labor market circumstances (Kosugi 2005a: 7–8; Wikipedia 2005, Internet). -

Hikikomori- a Generation in Crisis

Hikikomori- a Generation in Crisis Investigations into the phenomenon of acute social withdrawal in Japan Lars Nesser Master Thesis in Japanese- (AAS), 30 SP, Spring 2009, Institute of Cultural Studies and Oriental Languages (IKOS), University of Oslo i Abstract This paper is focused on acute social withdrawal in Japan, popularly referred to as the hikikomori phenomenon. I aim to investigate and analyse the discourse on hikikomori in the socio- historical context of post- bubble Japan. I argue that the 90s or the ‘lost decade’ of Japan plays a major part as the context in which hikikomori was constituted as a unique phenomenon of Japan and as a part of a larger social crisis. To my family, friends and Miki Table of Contents Chapter 1- Introduction...................................................................................... 1 1.1- Background ................................................................................................................... 1 1.2- Main argument.............................................................................................................. 4 1.3- Research Question ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4- Research method........................................................................................................... 4 1.4.1- Discourse.................................................................................................. 5 1.4.2- Nihonjinron in discourse ......................................................................... -

No Time and No Place in Japan's Queer Popular Culture

NO TIME AND NO PLACE IN JAPAN’S QUEER POPULAR CULTURE BY JULIAN GABRIEL PAHRE THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Professor Robert Tierney ABSTRACT With interest in genres like BL (Boys’ Love) and the presence of LGBT characters in popular series continuing to soar to new heights in Japan and abroad, the question of the presence, or lack thereof, of queer narratives in these texts and their responses has remained potent in studies on contemporary Japanese visual culture. In hopes of addressing this issue, my thesis queries these queer narratives in popular Japanese culture through examining works which, although lying distinctly outside of the genre of BL, nonetheless exhibit queer themes. Through examining a pair of popular series which have received numerous adaptations, One Punch Man and No. 6, I examine the works both in terms of their content, place and response in order to provide a larger portrait or mapping of their queer potentiality. I argue that the out of time and out of place-ness present in these texts, both of which have post-apocalyptic settings, acts as a vehicle for queer narratives in Japanese popular culture. Additionally, I argue that queerness present in fanworks similarly benefits from this out of place and time-ness, both within the work as post-apocalyptic and outside of it as having multiple adaptations or canons. I conclude by offering a cautious tethering towards the future potentiality for queer works in Japanese popular culture by examining recent trends among queer anime and manga towards moving towards an international stage. -

Block 9 Collection Schedule Calendar

Fujisawa-shiFujisawa-shi KKankyo-Jigyo-Centerankyo-Jigyo-Center (Environmental(Environmental MManagementanagement CCenter)enter) For Your Records Fiscal 2020 From April 2020 to March 2021 TELTEL 04660466-8787-39123912 FFAXAXAX 04660466-8787-97799779 BlockBlock 9 CCollectionollection SSchedulechedule CCalendaralendar The City of Fujisawa *This undertaking will be put in place after the decision on the budget for fiscal 2020. Address List *(Part ⑧) … Refer to block 8 of the calendar. List of Jichikai, Chonaikai 516~654・656~700 Ishikawa 18 (juhachi) gaiku-nagomikai Shiei-takinosawa Pastral Hasegawa 3 Chome 32 ban 2~13・15~20 33・35・36 ban Estrella Shonan Charmant Corpo Shonan Lite Town Hatori-honson Inari 1190-5 Ooba 5042 kyojusha-kumiai Shonan Espace Hatori-maruyama Omotego Shonan-koito dai-2 Jutaku Hatori-mukai Endo 621~789・810~954 Orido Shonan-shiroyama Hanezawa Ooba 592~6797 Kitanoya Shonan Sky Heights Hanezawa dai-1 All Area(with the exception of the QAS Fujisawa Shonan-seibu Hanezawa dai-2 Jonan 1~5 Chome 4 chome 10 ban 30-38 of the Clio Tsujido-nibankan Shonan Lite Town E-Block Hanezawa dai-3 Hikiji neighborhood association) Clio Fujisawa-gobankan Shonan Lite Town B-Chiku Fujisawa Hanezawa-higashi-danchi Green Blue Tsujido- 2 ban 20・21・32~35 3 ban Shiroyama Famile Fujisawa-jonan 2 Chome Gracia Shonan Lite Town Shiroyama dai-2 Fujikai kandai 4 ban 26・41・42 5~13 ban Grace Hatori Sotetsu-Oobajutaku-juminkumiai Fujisawa F 2 ban4~39・40・45 3 ban7(Part⑧)・8~41 Koito Dia Palace Shonan Lite Town Fujisawa-seibu-danchi 3 gaiku-kyodojutaku 1 Chome -

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan Japan’s first professionally produced, commercially marketed and nationally distributed gay lifestyle magazine, Barazoku (‘The Rose Tribes’), was launched in 1971. Publicly declaring the beauty and normality of homosexual desire, Barazoku electrified the male homosexual world whilst scandalizing mainstream society, and sparked a vibrant period of activity that saw the establishment of an enduring Japanese media form, the homo magazine. Using a detailed account of the formative years of the homo magazine genre in the 1970s as the basis for a wider history of men, this book examines the rela- tionship between male homosexuality and conceptions of manliness in postwar Japan. The book charts the development of notions of masculinity and homo- sexual identity across the postwar period, analysing key issues including public/ private homosexualities, inter-racial desire, male–male sex, love and friendship; the masculine body; and manly identity. The book investigates the phenomenon of ‘manly homosexuality’, little treated in both masculinity and gay studies on Japan, arguing that desires and individual narratives were constructed within (and not necessarily outside of) the dominant narratives of the nation, manliness and Japanese culture. Overall, this book offers a wide-ranging appraisal of homosexuality and manliness in postwar Japan, that provokes insights into conceptions of Japanese masculinity in general. Jonathan D. Mackintosh is Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Birkbeck, University of London,