Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eating After the Triple Disaster: New Meanings of Food in Three Post-3.11 Texts

EATING AFTER THE TRIPLE DISASTER: NEW MEANINGS OF FOOD IN THREE POST-3.11 TEXTS by ROSALEY GAI B.A., The University of Chicago, June 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2020 © Rosaley Gai, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Eating After the Triple Disaster: New Meanings of Food in Three Post-3.11 Texts submitted by Rosaley Gai in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Sharalyn Orbaugh, Professor, Asian Studies, UBC Supervisor Christina Yi, Associate Professor, Asian Studies, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Ayaka Yoshimizu, Assistant Professor of Teaching, Asian Studies, UBC Supervisory Committee Member ii ABstract Known colloquially as “3.11,” the triple disaster that struck Japan’s northeastern region of Tōhoku on March 11, 2011 comprised of both natural (the magnitude 9.0 earthquake and resultant tsunami) and humanmade (the nuclear meltdown at the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant incurred due to post-earthquake damage) disasters. In the days, weeks, months, and years that followed, there was an outpouring of media reacting to and reflecting on the great loss of life and resulting nuclear contamination of the nearby land and sea of the region. Thematically, food plays a large role in many post-3.11 narratives, both through the damage and recovery of local food systems after the natural disasters and the radiation contamination that to this day stigmatizes regionally grown food. -

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

DAFTAR PUSTAKA.Pdf

DAFTAR PUSTAKA 174th Diet Meeting Report, the Government of Japan, http://japan.kantei.go.jp/hatoyama/statement/201001/29siseihousin_e.htm l diakses pada 26 Juni 2018. 60JPID, 60 Tahun Indonesia-Jepang: Rangkaian acara utama di 2018, diakses dari https://www.60jpid.com/id/kalender.php pada 7 Juli 2018. 60JPID, Duta Persahabatan, diakses dari https://www.60jpid.com/id/duta-persahabatan.php pada 7 Juli 2018. 60JPID, Tentang Acara Peringatan, diakses dari https://www.60jpid.com/id/tentang.php pada 7 Juli 2018. AKB48, [MV Full] # 好 き な ん だ / AKB48 (Youtube, 2017), diakses dari https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zK_e8mCa5H0 pada 8 Juli 2018. AKB48. Chronicle. diakses dari http://www.akb48.co.jp/about/chronicle/ pada 22 July 2017. AKB48. Company. diakses dari http://www.akb48.co.jp/company pada 22 July 2017. Akibanation,AKB48 Melanjutkan Proyek Dareka No Tameni Tahun Ini, diakses dari https://www.akibanation.com/akb48-melanjutkan-proyek-dareka-no-tame ni-di-tahun-ini/ pada 8 Juli 2018. Amari, Akira. Pentingnya JIEPA, diakses dari https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2008/06/30/01251714/pentingnya.jiepa pada 28 Juni 2018. Antaranews, Melody JKT48 Jadi Duta Pertanian dan Pangan ASEAN-Jepang, diakses dari https://www.antaranews.com/berita/689766/melody-jkt48-jadi-duta-perta nian-dan-pangan-asean-jepang pada 6 Juli 2018. Arai, Hisamitsu. “Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters”, international Journal of Intellectual Property Law, Economy and Management 1 (2005) 5–12, diakses dari https://www.ipaj.org/english_journal/pdf/Intellectual_Property_Strategy.p df pada 29 Juni 2018. Badan Pusat Statistik, Realisasi Investasi Penanaman Modal Luar Negeri Menurut Negara (juta US$), 2000-2017, diakses dari https://www.bps.go.id/statictable/2014/01/15/1319/realisasi-investasi-pen anaman-modal-luar-negeri-menurut-negara-font-class-font827171-sup-1-s up-font-font-class-font727171-juta-us-2000-2016.html pada 28 Juni 2018. -

Willieverbefreelikeabird Ba Final Draft

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Fashion Subcultures in Japan A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Inga Guðlaug Valdimarsdóttir Kt: 0809883039 Leðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorkellsdóttir September 2015 1 Abstract This thesis discusses the history of the street fashion styles and its accompanying cultures that are to be found on the streets of Japan, focusing on the two most well- known places in Tokyo, namely Harajuku and Shibuya, as well as examining if the economic turmoil in Japan in the 1990s had any effect on the Japanese street fashion. The thesis also discusses youth cultures, not only those in Japan, but also in North- America, Europe, and elsewhere in the world; as well as discussing the theories that exist on the relation of fashion and economy of the Western world, namely in North- America and Europe. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the possible causes of why and how the Japanese street fashion scene came to be into what it is known for today: colorful, demiurgic, and most of all, seemingly outlandish to the viewer; whilst using Japanese society and culture as a reference. Moreover, the history of certain street fashion styles of Tokyo is to be examined in this thesis. The first chapter examines and discusses youth and subcultures in the world, mentioning few examples of the various subcultures that existed, as well as introducing the Japanese school uniforms and the culture behind them. The second chapter addresses how both fashion and economy influence each other, and how the fashion in Japan was before its economic crisis in 1991. -

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

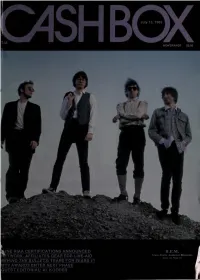

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

“Down the Rabbit Hole: an Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion”

“Down the Rabbit Hole: An Exploration of Japanese Lolita Fashion” Leia Atkinson A thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Studies in the Program of Anthropology with the intention of obtaining a Master’s Degree School of Sociology and Anthropology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Leia Atkinson, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract An ethnographic work about Japanese women who wear Lolita fashion, based primarily upon anthropological field research that was conducted in Tokyo between May and August 2014. The main purpose of this study is to investigate how and why women wear Lolita fashion despite the contradictions surrounding it. An additional purpose is to provide a new perspective about Lolita fashion through using interview data. Fieldwork was conducted through participant observation, surveying, and multiple semi-structured interviews with eleven women over a three-month period. It was concluded that women wear Lolita fashion for a sense of freedom from the constraints that they encounter, such as expectations placed upon them as housewives, students or mothers. The thesis provides a historical chapter, a chapter about fantasy with ethnographic data, and a chapter about how Lolita fashion relates to other fashions as well as the Cool Japan campaign. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the carrying out of my thesis, I have received an immense amount of support, for which I am truly thankful, and without which this thesis would have been impossible. I would particularly like to thank my supervisor, Vincent Mirza, as well as my committee members Ari Gandsman and Julie LaPlante. I would also like to thank Arai Yusuke, Isaac Gagné and Alexis Truong for their support and advice during the completion of my thesis. -

JKT48 As the New Wave of Japanization in Indonesia Rizky Soraya Dadung Ibnu Muktiono English Department, Universitas Airlangga

JKT48 as the New Wave of Japanization in Indonesia Rizky Soraya Dadung Ibnu Muktiono English Department, Universitas Airlangga Abstract This paper discusses the cultural elements of JKT48, the first idol group in Indonesia adopting its Japanese sister group‘s, AKB48, concept. Idol group is a Japanese genre of pop idol. Globalization is commonly known to trigger transnational corporations as well as to make the spreading of cultural value and capitalism easier. Thus, JKT48 can be seen as the result of the globalization of AKB48. It is affirmed by the group management that JKT48 will reflect Indonesian cultures to make it a unique type of idol group, but this statement seems problematic as JKT48 seems to be homogenized by Japanese cultures in a glance. Using multiple proximities framework by La Pastina and Straubhaar (2005), this study aims to present the extent of domination of Japanese culture occurs in JKT48 by comparing cultural elements of AKB48 and JKT48. The author observed the videos footages and conducted online survey and interviews to JKT48 fans. The research shows there are many similarities between AKB48 and JKT48 as sister group. It is then questioned how the fans achieved proximity in JKT48 which brings foreign culture and value. The research found that JKT48 is the representation of AKB48 in Indonesia with Japanese cultural values and a medium to familiarize Japanese culture to Indonesia. Keywords: JKT48, AKB48, idol group, multiple proximities, homogenization Introduction “JKT48 will reflect the Indonesian cultures to fit as a new and unique type of idol group”. (JKT48 Operational Team, 2011) “JKT48 will become a bridge between Indonesia and Japan”. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

METRO in Focus 「The Dark Side to Being a Star in a Pop Brand」

12 METRO Tuesday, June 3, 2014 METRO in focus AKB48 are a Japanese girl band with a revolving roster of 140 The band play a members across gig at their own The band has several teams theatre The dark side to sold more than 30m almost every day records The group’sroup’s firstfirst 23 singleses all went to being a star in No.1 in thethe JapaneseJapanese charts.harts. 18 Auditions to join of themm have sold AKB48 are held moree than 1m1m twice ccopiesopies a pop brand a year T WAS a bloody intrusion into the world A week ago, two members of Japanese pop of bright and shiny pop that – in the eyes group AKB48 were injured by an attacker of Japanese teen fans – was akin to the armed with a saw at a meet and greet for stars of One Direction or Little Mix fans. But what makes this girl band – which being put in the firing line. has 140 members – so successful and so ITwo members of girl band AKB48 – Rina controversial? ROSS McGUINNESS reports... Kawaei, 19, and Anna Iriyama, 18 – were injured by an attacker wielding a saw during a meet and greet. and creepy J-Pop phenomenon – so carefully They were treated for wounds to their head contrived, it makes Simon Cowell’s stable of and hands and a 24-year-old was arrested on manufactured pop acts look like free-wheel- AKB is short for Akihabara, suspicion of attempted murder. ing rock ‘n’ rollers. the area of Tokyo where But as the group’s young followers got over Let’s start with the band’s latest single – their theatre is based. -

Meyer Tech Pak012617.Indd

• Technical Information • Policies & Procedures • Fee Schedule for Rental & Services LOAD-IN AREA The loading dock is located on stage level, directly off upstage right. The dock has one 8’-0” wide x 10’-0” high (2.44m x 3.05m) overhead door. Dock height is 24” (.61m). There is NO leveler, and there is NO truck ramp. The loading area is 16’ wide x 22’ long with 12’ ceilings, in a wedge shape. Access to stage is through a 10’ wide x 11’ high overhead door upstage right. Access to the dressing rooms is by stairs or by elevator. CARPENTRY Seating Capacity Maximum Capacity: 1011 Orchestra 537 Grand Tier: 90 Mezzanine: 384 Handicapped Accessible: 8 Additional on Grand Tier Level Stage Dimensions Proscenium w: 49’-6” (15.09m) h:23’-0” (7.01m) Depth (plaster to back wall) 28’-0” (8.53m) Apron Curved 5’-0” (1.52m) at centerline Wing Space • Stage right 10’-0” (~3.05m) • Stage left 13’-0” (~3.96m) Orchestra Pit none Stage to Audience 4’-0” (1.21m) NFORMATION Stage Floor Material: 1/4” hardboard (Duron) I Color: Black Condition: Good Sub floor: 1 layer of 3/4” plywood 2x4 sleepers (24” O.C.) on resilient pads House Drapery: House Curtain- Scarlet; Manual Fly Item Number Material WxH Legs 8 black velour 10’ x 25’ (3.05m x 7.62m) Borders 4 black velour 60’ x 10’ (18.23m x 3.05m) Full Black 2 black velour 60’ x 25’ (18.23m x 7.62m) Line Set Data: Grid height: 53’-9” (16.38m) High trim: 50’-11” (15.52m) Low trim: 5’-8” (1.72m) Total Line Sets: 26 single purchase Arbor Capacity: 1500 lbs (680kg) ECHNICAL Weight Available: 8702 lbs (3947kg) Weight Size: 19 lbs (8.6 kg) Pipe Length: 60’-0” (18.29m) T Pipe size: 26 @ 1-1/2” Schedule 40 Lock Rail: Stage Left, stage level Line Plot: Enclosed Shop Area: There is NO on-site scenery shop, and there is no off-stage area for working on scenery. -

Ridgeley È Stato Una Delle Due Metà Di Una WHAM! Delle Pop Band Più Importanti Della Storia

Pagine tratte da www.epc.it - Tutti i diritti riservati Andrew Ridgeley è stato una delle due metà di una WHAM! WHAM! delle pop band più importanti della storia. Adesso, per la prima volta, racconta i retroscena degli Wham!, la sua amicizia lunga una vita con George Michael, e di come loro due insieme cambiarono la scena musicale ANDREW degli anni Ottanta grazie a una serie di allegri successi, amati ancora oggi proprio come quando fecero irruzione per la prima volta nelle radio e nei cuori degli adolescenti. GEORGE GEORGE & IO Watford, 1975. Era il primo giorno del nuovo trimestre RIDGELEY scolastico e due adolescenti, Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou e Andrew Ridgeley, si incontrarono per la prima volta. Sarebbero diventati l’uno il migliore amico dell’altro. Ma non erano il football, o la moda, o le ragazze a unirli (in realtà, le ragazze: sì). Scoprirono invece di essere tutt’e due pazzi per la musica. Spinti dalla gioia assoluta della loro «Gli Wham! raccontavano lo slancio, la libertà, passione per il pop, inseguirono quello che alle loro famiglie e l’esuberanza della giovinezza. e agli amici sembrava un sogno impossibile. Quel sogno Incarnavano l’idea che tutto è possibile nel 1982 li portò a una prima, esuberante, indimenticabile quando sei giovane». esibizione a Top of the Pops, che li proiettò in una fama immediata. Da adolescente, Andrew Ridgeley era assolutamente Nei quattro anni successivi Andrew e George si ritrovarono sicuro di una cosa: avrebbe fondato una band e scritto ANDREW su un incredibile ottovolante di successo e celebrità, che canzoni.