Japanese Salarymen: on the Way to Extinction?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute”Culture

《藝術學研究》 2015 年 6 月,第十六期,頁 131-168 Mariko Mori and the Globalization of Japanese “Cute” Culture: Art and Pop Culture in the 1990s SooJin Lee Abstract This essay offers a cultural-historical exploration of the significance of the Japanese artist Mariko Mori (b. 1967) and her emergence as an international art star in the 1990s. After her New York gallery debut show in 1995, in which she exhibited what would later become known as her Made in Japan series— billboard-sized color photographs of herself striking poses in various “cute,” video-game avatar-like futuristic costumes—Mori quickly rose to stardom and became the poster child for a globalizing Japan at the end of the twentieth century. I argue that her Made in Japan series was created (in Japan) and received (in the Western-dominated art world) at a very specific moment in history, when contemporary Japanese art and popular culture had just begun to rise to international attention as emblematic and constitutive of Japan’s soft power. While most of the major writings on the series were published in the late 1990s, problematically the Western part of this criticism reveals a nascent and quite uneven understanding of the contemporary Japanese cultural references that Mori was making and using. I will examine this reception, and offer a counter-interpretation, analyzing the relationship between Mori’s Made in Japan photographs and Japanese pop culture, particularly by discussing the Japanese mass cultural aesthetic of kawaii (“cute”) in Mori’s art and persona. In so doing, I proffer an analogy between Mori and popular Japanimation characters, SooJin Lee received her PhD in Art History from the University of Illinois-Chicago and was a lecturer at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. -

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

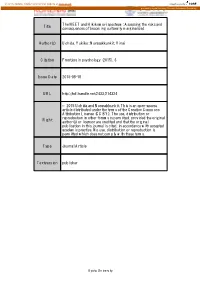

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014

Copyright by Maeri Megumi 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Maeri Megumi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature Committee: Kirsten C. Fischer, Supervisor Sung-Sheng Yvonne Chang Anne M. Martinez Nancy K. Stalker John W. Traphagan Susan J. Napier Religion, Nation, Art: Christianity and Modern Japanese Literature by Maeri Megumi, B.HOME ECONOMICS; M.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to express the deepest gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Kirsten Cather (Fischer). Without her guidance and encouragement throughout the long graduate student life in Austin, Texas, this dissertation would not have been possible. Her insight and timely advice have always been the source of my inspiration, and her positive energy and patience helped me tremendously in many ways. I am also indebted to my other committee members: Dr. Nancy Stalker, Dr. John Traphagan, Dr. Yvonne Chang, Dr. Anne Martinez, and Dr. Susan Napier. They nourished my academic development throughout the course of my graduate career both directly and indirectly, and I am particularly thankful for their invaluable input and advice in shaping this dissertation. I would like to thank the Department of Asian Studies for providing a friendly environment, and to the University of Texas for offering me generous fellowships to make my graduate study, and this dissertation, possible. -

Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and The

Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and the Subsequent Rise of Activist Movements: Combatting Four Forms of Hara to Create a More Gender Equal Workplace by Rachel Grant A THESIS Presented to the Department of Japanese and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Rachel Grant for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Japanese to be taken June 2016 Title: Japanese Workplace Harassment Against Women and the Subsequent Rise of Activist Movements Approved: {1 ~ Alisa Freedman The Japanese workplace has traditionally been shaped by a large divide between the gender roles of women and men. This encompasses areas such as occupational expectations, job duties, work hours, work pay, work status, and years of work. Part of this struggle stems from the pressure exerted by different sides of society, pushing women to fulfill the motherly home-life role, the dedicated career woman role, or a merge of the two. Along with these demands lie other stressors in the workplace, such as harassment Power harassment, age discrimination, sexual harassment, and maternity harassment, cause strain and anxiety to many Japanese businesswomen. There have been governmental refonns put in place, such as proposals made by the Prime Minister of Japan, in an attempt to combat this behavior. More recently, there have been various activist grassroots groups that have emerged to try to tackle the issues surrounding harassment against women. In this thesis, I make the argument that these groups are an essential component in the changing Japanese workplace, where women are gaining a more equal balance to men. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

Evolution of Male Self-Expression. the Socio-Economic Phenomenon As Seen in Japanese Men’S Fashion Magazines

www.ees.uni.opole.pl ISSN paper version 1642-2597 ISSN electronic version 2081-8319 Economic and Environmental Studies Vol. 18, No 1 (45/2018), 211-248, March 2018 Evolution of male self-expression. The socio-economic phenomenon as seen in Japanese men’s fashion magazines Mariusz KOSTRZEWSKI1, Wojciech NOWAK2 1 Warsaw University of Technology, Poland 2 Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland Abstract: Visual aesthetics represented in Western media by the name of “Japanese style”, is presented from the point of view of women’s fashion, especially in the realm of pop-culture. The resources available for non- Japanese reader rarely raise the subject of Japanese men’s fashion in the context of giving voice to self- expression by means of style and clothing. The aim of this paper is to supplement the information on the socio- economic correlation between the Japanese economy, fashion market, and self-expression of Japanese men, including their views on masculinity and gender, based on the profile of Japanese men’s fashion magazines readers. The paper presents six different fashion styles indigenous to metropolitan Japan, their characteristics, background and development, emphasizing the connections to certain lifestyle and socio-economic occurrences, resulting in an emergence of a new pattern in masculinity – the herbivorous man, whose requirements and needs are analyzed considering his status in the consumer market and society. Keywords: salaryman, kireime kei, salon mode kei, ojii boy kei, gyaru-o kei, street mode kei, mode kei, sōshokukei danshi, sōshoku danshi, Non-no boy, Popeye boy, the city boy, Japan, fashion, consumer market JEL codes: H89, I31, J17, Z00 https://doi.org/10.25167/ees.2018.45.13 Correspondence Address: Mariusz Kostrzewski, Faculty of Transport, Warsaw University of Technology, Koszykowa 75, 00-662 Warszawa, Poland. -

Dansō, Gender, and Emotion Work in a Tokyo Escort Service

WALK LIKE A MAN, TALK LIKE A MAN: DANSŌ, GENDER, AND EMOTION WORK IN A TOKYO ESCORT SERVICE A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 MARTA FANASCA SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ...................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration and Copyright Statement .................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 Significance and aims of the research .................................................................................. 12 Outline of the thesis ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1 Masculinity in Japan ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2 Dansō and gender definition