Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey

06-ORD 70H-002AA 7 Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey - 2005 Survey - September 2006 Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Preface The survey on “Japanese manufacturing affiliates in Europe and Turkey” has been conducted 22 times since the first survey in 1983*. The latest survey, carried out from January 2006 to February 2006 targeting 16 countries in Western Europe, 8 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and Turkey, focused on business trends and future prospects in each country, procurement of materials, production, sales, and management problems, effects of EU environmental regulations, etc. The survey revealed that as of the end of 2005 there were a total of 1,008 Japanese manufacturing affiliates operating in the surveyed region --- 818 in Western Europe, 174 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 16 in Turkey. Of this total, 291 affiliates --- 284 in Western Europe, 6 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 1 in Turkey --- also operate R & D or design centers. Also, the number of Japanese affiliates who operate only R & D or design centers in the surveyed region (no manufacturing operations) totaled 129 affiliates --- 125 in Western Europe and 4 in Central and Eastern Europe. In this survey we put emphasis on the effects of EU environmental regulations on Japanese manufacturing affiliates. We would like to express our great appreciation to the affiliates concerned for their kind cooperation, which have enabled us over the years to constantly improve the survey and report on the results. We hope that the affiliates and those who are interested in business development in Europe and/or Turkey will find this report useful. -

Remote Control Code List

Remote Control Code List MDB1.3_01 Contents English . 3 Čeština . 4 Deutsch . 5 Suomi . 6 Italiano . 7. Nederlands . 8 Русский . .9 Slovenčina . 10 Svenska . 11 TV Code List . 12 DVD Code List . 25 VCR Code List . 31 Audio & AUX Code List . 36 2 English Remote Control Code List Using the Universal Remote Control 1. Select the mode(PVR, TV, DVD, AUDIO) you want to set by pressing the corresponding button on the remote control. The button will blink once. 2. Keep pressing the button for 3 seconds until the button lights on. 3. Enter the 3-digit code. Every time a number is entered, the button will blink. When the third digit is entered, the button will blink twice. 4. If a valid 3-digit code is entered, the product will power off. 5. Press the OK button and the mode button will blink three times. The setup is complete. 6. If the product does not power off, repeat the instruction from 3 to 5. Note: • When no code is entered for one minute the universal setting mode will switch to normal mode. • Try several setting codes and select the code that has the most functions. 3 Čeština Seznam ovládacích kódů dálkového ovladače Používání univerzálního dálkového ovladače 1. Vyberte režim (PVR, TV, DVD, AUDIO), který chcete nastavit, stisknutím odpovídajícího tlačítka na dálkovém ovladači. Tlačítko jednou blikne. 2. Stiskněte tlačítko na 3 sekundy, dokud se nerozsvítí. 3. Zadejte třímístný kód. Při každém zadání čísla tlačítko blikne. Po zadání třetího čísla tlačítko blikne dvakrát. 4. Po zadání platného třímístného kódu se přístroj vypne. -

Touch Panel Display

Quick Setup Guide PA-TDU-001 Touch Panel Display Before using this printer, be sure to read this Quick Setup Guide. We suggest that you keep this manual in a handy place for future reference. Please visit us at http://support.brother.com/ where you can get product support and answers to frequently asked questions (FAQs). ENG Safety Precautions English Indicates a potentially hazardous situation which, if not avoided, WARNING could result in death or serious injuries. Keep out of the reach of children, particularly infants. Otherwise, injuries may result. Indicates a potentially hazardous situation which, if not avoided, IMPORTANT may result in damage to property or loss of product functionality. Place the printer on a stable surface, such as a level desk, before installing or removing the touch panel display. Press touch panel keys with the tip of your finger. Using a fingernail, mechanical pencil, screwdriver or any other sharp or hard object on the touch panel may damage it. Do not press touch panel keys with more force than necessary. Otherwise, damage may result. Be careful not to scrape or scratch the surface of the touch panel or display with a hard object. When moving the printer, do not carry it by the touch panel or the display. When installing the touch panel display onto the printer, do not allow the cord to be squashed. Otherwise, damage or malfunctions may result. Before opening the RD Roll compartment top cover, close the LCD. Do not drop the printer or subject it to strong shocks. Wipe any dust or dirt from the printer with a soft, dry cloth. -

ESG in Japan: Misunderstood & Underestimated

ESG in Japan: Misunderstood & Underestimated Comgest’s investment approach is grounded on thorough fundamental analysis carried out by experienced portfolio managers located in the markets where they invest. Seasoned investors who spend years researching and building relationships with local companies develop an understanding of cultural and regional nuances that are not obvious to outsiders. We believe this leads to perceptive investment insights that few other firms can match. This white paper, authored by Comgest PM Richard Kaye who has spent almost three decades living and investing in Japan, illustrates how experienced local investors can spot opportunities that others miss. Richard Kaye Analyst / Portfolio Manager, Japan Japan is in the process of being rediscovered after a “lost generation” in which it was largely neglected by both domestic Richard Kaye joined Comgest in 2009 and international asset allocators. However, despite the renewed and is a Tokyo-based Analyst and interest in this fascinating and broad market, international investors Portfolio Manager specialising in remain wary of corporate Japan’s ESG credentials. Japanese Japanese equities. With a wealth of companies have a reputation for being behind their global experience in Japanese equities, peers when it comes to ESG activities and transparency. We Richard became co-lead of Comgest’s believe that this characterisation is misleading: many Japanese Japan equity strategy upon joining the companies appear to be ahead of the rest of the world in terms of Group. He started his career in 1994 as environmental technologies and have a deep commitment to their an Analyst with the Industrial Bank of founding vision and social purpose. -

Japan 500 2010 A-Z

FT Japan 500 2010 A-Z Japan rank Company 2010 77 Bank 305 Abc-Mart 280 Accordia Golf 487 Acom 260 Adeka 496 Advantest 156 Aeon 85 Aeon Credit Service 340 Aeon Mall 192 Air Water 301 Aisin Seiki 89 Ajinomoto 113 Alfresa Holdings 300 All Nippon Airways 109 Alps Electric 433 Amada 213 Aoyama Trading 470 Aozora Bank 293 Asahi Breweries 86 Asahi Glass 55 Asahi Kasei 104 Asics 330 Astellas Pharma 40 Autobacs Seven 451 Awa Bank 413 Bank of Iwate 472 Bank of Kyoto 208 Bank of Yokohama 123 Benesse Holdings 170 Bridgestone 52 Brother Industries 212 Canon 6 Canon Marketing Japan 320 Capcom 428 Casio Computer 310 Central Glass 484 Central Japan Railway 42 Century Tokyo Leasing 397 Chiba Bank 144 Chiyoda 264 Chubu Electric Power 35 Chugai Pharmaceuticals 71 Chugoku Bank 224 Chugoku Electric Power 107 Chuo Mitsui Trust 130 Circle K Sunkus 482 Citizen Holding 283 Coca-Cola West 345 Comsys Holdings 408 Cosmo Oil 323 Credit Saison 247 Dai Nippon Printing 81 Daicel Chemical Industries 271 Daido Steel 341 Daihatsu Motor 185 Daiichi Sankyo 56 Daikin Industries 59 Dainippon Screen Mnfg. 453 Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma 201 Daio Paper 485 Japan rank Company 2010 Daishi Bank 426 Daito Trust Construction 137 Daiwa House Industry 117 Daiwa Securities Group 84 Dena 204 Denki Kagaku Kogyo 307 Denso 22 Dentsu 108 Dic 360 Disco 315 Don Quijote 348 Dowa 339 Duskin 448 Eaccess 486 East Japan Railway 18 Ebara 309 Edion 476 Eisai 70 Electric Power Development 140 Elpida Memory 189 Exedy 454 Ezaki Glico 364 Familymart 226 Fancl 439 Fanuc 23 Fast Retailing 37 FCC 493 FP 500 Fuji Electric 326 Fuji Heavy Industries 186 Fuji Media 207 Fuji Oil 437 Fujifilm 38 Fujikura 317 Fujitsu 54 Fukuoka Financial 199 Fukuyama Transp. -

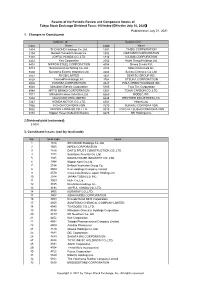

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

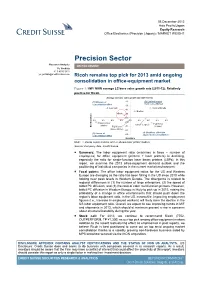

Precision Sector

05 December 2012 Asia Pacific/Japan Equity Research Office Electronics (Precision (Japan)) / MARKET WEIGHT Precision Sector Research Analysts SECTOR REVIEW Yu Yoshida 81 3 4550 9815 [email protected] Ricoh remains top pick for 2013 amid ongoing consolidation in office-equipment market Figure 1: HW / NHW average LC base sales growth rate (2011-12): Relatively positive for Ricoh Average LC base sales growth rate (2011-2012) (1) Winners of 8% (3) Limited impact consolidation effect from consolidation 6% Lexmark Konica Minolta 4% Brother Ricoh 2% 0% -8% -6% -4% -2% 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% -2% Canon (Laser Fuji Xerox printer) Canon (Copier) Non-hardware Fuji Xerox -4% (Copier) (Laser printer) -6% (4) Unable to offset the (2) Losers of -8% consolidation effect impact from consolidation Hardware Note: × shows copier makers and △ shows laser printer makers Source: Company data, Credit Suisse ■ Summary: The labor equipment ratio (machines in force ÷ number of employees) for office equipment (printers + laser printers) is declining, especially the ratio for single-function laser beam printers (LBPs). In this report, we examine the 2013 office-equipment demand outlook and the positioning of individual companies in the current market environment. ■ Focal points: The office labor equipment ratios for the US and Western Europe are diverging as the ratio has been falling in the US since 2010 while holding near peak levels in Western Europe. The divergence is related to regional differences in (1) the number of large enterprises, (2) the speed of tablet PC diffusion, and (3) the ratio of color multifunction printers. However, tablet PC diffusion in Western Europe is likely to pick up in 2013, raising the probability of a change in office environments that should push down the region’s labor equipment ratio. -

Asahi Group's Management Team (As of April 1, 2016)

Asahi Group’s Management Team (As of April 1, 2016) Back row, from the left: Tetsuo Tsunoda, Yumiko Waseda, Katsutoshi Saito, Tadashi Ishizaki, Mariko Bando, Naoki Tanaka, Tatsuro Kosaka, Akira Muto Front row, from the left: Ryoichi Kitagawa, Noboru Kagami, Katsutoshi Takahashi, Naoki Izumiya, Akiyoshi Koji, Yoshihide Okuda, Kenji Hamada Naoki Izumiya Akiyoshi Koji Katsutoshi Takahashi Chairman and Representative Director, CEO President and Representative Director, COO Managing Director and Managing Corporate Officer Apr. 1972 Joined the Company Apr. 1975 Joined the Company Apr. 1977 Joined Yoshida Kogyo K.K. Mar. 2000 Corporate Officer Sep. 2001 Corporate Officer (currently YKK Corporation) Mar. 2003 Director Mar. 2003 Managing Director, Asahi Soft Drinks Co., Ltd. May 1991 Joined the Company Mar. 2004 Managing Director Mar. 2006 Senior Managing Director, Mar. 2008 Corporate Officer Mar. 2009 Senior Managing Director Asahi Soft Drinks Co., Ltd. Mar. 2013 Director and Corporate Officer Mar. 2010 President and Representative Director Mar. 2007 Managing Director and Managing Corporate Officer Mar. 2015 Managing Director and Managing Corporate Mar. 2014 President and Representative Director, CEO Jul. 2011 Director Officer (current position) Mar. 2016 Chairman and Representative Director, CEO President and Representative Director, (current position) Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Mar. 2016 President and Representative Director, COO (current position) Yoshihide Okuda Noboru Kagami Kenji Hamada Managing Director and Director and Corporate Officer Director and Corporate Officer Managing Corporate Officer (CFO) Apr. 1978 Joined Konishiroku Photo Industry Co., Ltd. Apr. 1982 Joined the Company Apr. 1986 Joined the Company (currently Konica Minolta, Inc.) Sep. 2012 Corporate Officer Mar. 2014 Corporate Officer Sep. 1988 Joined the Company General Manager, Fukushima Brewery, General Manager, Corporate Strategy Section Mar. -

読む Notice of the 89Th Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Note: This document has been translated from a part of the Japanese original for reference purposes only. In the event of any discrepancy between this translated document and the Japanese original, the original shall prevail. The Company assumes no responsibility for this translation or for direct, indirect or any other forms of damages arising from the translation. (Stock Exchange Code 5631) June 1, 2015 To Shareholders with Voting Rights: Ikuo Sato Representative Director & President The Japan Steel Works, Ltd. 11-1, Osaki 1-chome, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo, Japan NOTICE OF THE 89TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS Dear Shareholders: We would like to express our appreciation for your continued support and patronage. You are cordially invited to attend the 89th Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of The Japan Steel Works, Ltd. (the “Company”). The meeting will be held for the purposes as described below. If you are unable to attend the meeting, you can exercise your voting rights in writing or via the Internet. Please review the attached Reference Documents for the General Meeting of Shareholders and exercise your voting rights by 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday, June 23, 2015, Japan time. If exercising your voting rights in writing, indicate your vote for or against the proposal on the enclosed Voting Rights Exercise Form and return it so that it is received by the above-mentioned deadline. If exercising your voting rights via the Internet, visit the Company’s Web site (http://www.web54.net) to exercise your voting rights, enter the voting rights exercise code and password that are indicated on the enclosed Voting Rights Exercise Form, follow the instructions on the screen and input your vote for or against each proposal by the above-mentioned deadline. -

Avm 40 | 50 Operatingmanual

AVM 40 | 50 OPERATING MANUAL UPDATES: www.anthemAV.com SOFTWARE VERSION 1.3x ™ SAFETY PRECAUTIONS READ THIS SECTION CAREFULLY BEFORE PROCEEDING! WARNING RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK DO NOT OPEN WARNING: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. The lightning flash with arrowpoint within an equilateral triangle warns of the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product’s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle warns users of the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the appliance. WARNING: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FIRE OR ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS PRODUCT TO RAIN OR MOISTURE AND OBJECTS FILLED WITH LIQUIDS, SUCH AS VASES, SHOULD NOT BE PLACED ON THIS PRODUCT. CAUTION: TO PREVENT ELECTRIC SHOCK, MATCH WIDE BLADE OF PLUG TO WIDE SLOT, FULLY INSERT. CAUTION: FOR CONTINUED PROTECTION AGAINST RISK OF FIRE, REPLACE THE FUSE ONLY WITH THE SAME AMPERAGE AND VOLTAGE TYPE. REFER REPLACEMENT TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. WARNING: UNIT MAY BECOME HOT. ALWAYS PROVIDE ADEQUATE VENTILATION TO ALLOW FOR COOLING. DO NOT PLACE NEAR A HEAT SOURCE, OR IN SPACES THAT CAN RESTRICT VENTILATION. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS 1. Read Instructions – All the safety and operating instructions should be read before the product is operated. 2. Retain Instructions – The safety and operating instructions should be retained for future reference. 3. Heed Warnings – All warnings on the product and in the operating instructions should be adhered to. -

To Our Shareholders and Customers Issues We Faceinfiscal2000

To Our Shareholders and Customers — The Dawn of a New Era — Review of Fiscal 1999 For the Japanese financial sector, fiscal 1999 During fiscal 1999, we strengthened our man- marked the start of a totally new era in the his- agement infrastructure and corporate structure tory of finance in Japan. by improving business performance, restructur- In August 1999, The Fuji Bank, Limited, ing operations, strengthening risk management The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited, and The and managing consolidated business activities Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited, reached full under a stronger group strategy. agreement to consolidate their operations into a comprehensive financial services group to be • Improving Business Performance called the Mizuho Financial Group. In the fol- We have identified the domestic corporate and lowing six months after the announcement, retail markets as our priority business areas. several other major Japanese financial institu- Our goals in these markets are to enhance our tions announced mergers and consolidations of products and services to meet the wide-ranging one form or another. needs of our customers, and to improve cus- At the same time, conditions in the financial tomer convenience by using information tech- sector changed dramatically as foreign-owned nology to diversify our service channels. financial institutions began in earnest to With respect to enhancing products and expand their presence in Japan, companies services, we focused on services provided to from other sectors started to move into the members of the Fuji First Club, a membership To Our Shareholders and Customers To financial business, and a number of Internet- reward program that offers special benefits to based strategic alliances were formed across dif- member customers, and on our product lineup ferent sectors and industries. -

39602NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ~, I '~\ \ ,'] lL r'f U !~ .J (f\ 15) ' '.\ \f1 \ \ Ii !I " \ 1\ I 11 fl ),l'l rt \r I' ! ' I \.1._) ~J "i \J ...... - L./ Lffi / t"r ,~ ~ .C;;':' - .oJ.';' C: '" () tl~j fJ'. (,\ pi :1. '," f -I: : ~'J n I'~ 1,,' (' I, i , , , ; " i , , Ii i' ~ I, I . $ ~; ( ~> (.' ;( ,] ;. 8~; q:: ij (}, q~ ~ ~1 " vd; ~S ~~ ~') r.E}rtiH]~~ '- ,. f){ I'· i 0....:1 ••>0 oj ::~] e O!iHl1l ~; , ,HHl f.hs Il(j~ rc~;ebll: ~ hr\:) ld1 ~~a~ ~. [1 ;;itHHl III 1HliH~iG~j 81 ~iln U .:I, Ih,;rlcH~m !)~ hi if"D u.~. DEPARli\1HH Of HjSHC~ U\W HUORCEMHH ASSISIJU~CE JHH~H4IS'Hunm~J NATIONAL CRIMiNAL JUSTiCE R[fH~ENCE SE~VICE WASHlt~GTO~t D.C. 20531 i I m e d "-.~-...,;- .i , j , .1 i", ,'j .1 ;j - '.j I j , . , "'. ANALYSIS OF ELECTRONIC RECORDING - IN THE ~lAGISTR/UES DIVISION - ,. ;.- , ~" ADA COUNTY IDAHO DISTRICT COURT , . " '''F. , ., . I " I . J .~ , ' , - I < .: '"- ~ " j " 'iii ~ - 1 February, 1974 ~ .' ',.. ',1. I ',< I '... j .... i . I Consultant: 'j Ernest H. Short '. NC,JRS MAR 81977 \ \ CRIMINAL COURTS TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT \ 2139 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20007 , .0'<, " (202) 686-3800 '. j 1 I Law Enforcement Assistance Administration Contract Number: J-LEAA-043-72 TABLE OF COrnErlTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION . II. ANALYSIS OF EXISTING SITUATIOil 2 A. THE t·1AGISTRATES DI VISION . 2 This report ,·ms prepared in' conjunction B. RECORDING PROCEEDINGS 4 with the Institute's Criminal Courts Technical Assistance Project) under a III.