Epidemiology and Clinical Outcomes of Snakebite in the Elderly: a Toxic Database Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

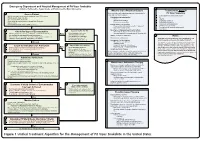

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Approach and Management of Spider Bites for the Primary Care Physician

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 149-153 Approach and management of spider bites for the primary care physician John Ashurst, DO,a Joe Sexton, MD,a Matt Cook, DOb From the Departments of aEmergency Medicine and bToxicology, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA. KEYWORDS: Summary The class Arachnida of the phylum Arthropoda comprises an estimated 100,000 species Spider bite; worldwide. However, only a handful of these species can cause clinical effects in humans because many Black widow; are unable to penetrate the skin, whereas others only inject prey-specific venom. The bite from a widow Brown recluse spider will produce local symptoms that include muscle spasm and systemic symptoms that resemble acute abdomen. The bite from a brown recluse locally will resemble a target lesion but will develop into an ulcerative, necrotic lesion over time. Spider bites can be prevented by several simple measures including home cleanliness and wearing the proper attire while working outdoors. Although most spider bites cause only local tissue swelling, early species identification coupled with species-specific man- agement may decrease the rate of morbidity associated with bites. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. More than 100,000 species of spiders are found world- homes and yards in the southwestern United States, and wide. Persons seeking medical attention as a result of spider related species occur in the temperate climate zones across bites is estimated at 50,000 patients per year.1,2 Although the globe.2,5 The second, Lactrodectus, or the common almost all species of spiders possess some level of venom, widow spider, are found in both temperate and tropical 2 the majority are considered harmless to humans. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous. -

Snakebite: the World's Biggest Hidden Health Crisis

Snakebite: The world's biggest hidden health crisis Snakebite is a potentially life-threatening neglected tropical disease (NTD) that is responsible for immense suffering among some 5.8 billion people who are at risk of encountering a venomous snake. The human cost of snakebite Snakebite Treatment Timeline Each year, approximately 5.4 million people are bitten by a snake, of whom 2.7 million are injected with venom. The first snake antivenom This leads to 400,000 people being permanently dis- produced, against the Indian Cobra. abled and between 83,000-138,000 deaths annually, Immunotherapy with animal- mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. 1895 derived antivenom has continued to be the main treatment for snakebite evenoming for 120 years Snakebite: both a consequence and a cause of tropical poverty The Fav-Afrique antivenom, 2014 produced by Sanofi Pasteur (France) Survivors of untreated envenoming may be left with permanently discontinued amputation, blindness, mental health issues, and other forms of disability that severely affect their productivity. World Health Organization Most victims are agricultural workers and children in 2018 (WHO) lists snakebite envenoming the poorest parts of Africa and Asia. The economic as a neglected tropical disease cost of treating snakebite envenoming is unimaginable in most communities and puts families and communi- ties at risk of economic peril just to pay for treatment. WHO launches a strategy to prevent and control snakebite envenoming, including a program targeting affected communities and their health systems Global antivenom crisis 2019 The world produces less than half of the antivenom it The Scientific Research Partnership needs, and this only covers 57% of the world’s species for Neglected Tropical Snakbites of venomous snake. -

Bitis Arietans) Venom, and Their Neutralization by Antivenom

Toxins 2014, 6, 1586-1597; doi:10.3390/toxins6051586 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article In Vitro Toxic Effects of Puff Adder (Bitis arietans) Venom, and Their Neutralization by Antivenom Steven Fernandez 1, Wayne Hodgson 1, Janeyuth Chaisakul 2, Rachelle Kornhauser 1, Nicki Konstantakopoulos 1, Alexander Ian Smith 3 and Sanjaya Kuruppu 3,* 1 Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Building 13E, Wellington Road, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (R.K.); [email protected] (N.K.) 2 Department of Pharmacology, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Monash University, Building 77, Wellington Road, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +61-3-9902-9372; Fax: + 61-3-9902-9500. Received: 24 November 2013; in revised form: 6 April 2014 / Accepted: 4 May 2014 / Published: 19 May 2014 Abstract: This study investigated the in vitro toxic effects of Bitis arietans venom and the ability of antivenom produced by the South African Institute of Medical Research (SAIMR) to neutralize these effects. The venom (50 µg/mL) reduced nerve-mediated twitches of the chick biventer muscle to 19% ± 2% of initial magnitude (n = 4) within 2 h. This inhibitory effect of the venom was significantly attenuated by prior incubation of tissues with SAIMR antivenom (0.864 µg/µL; 67% ± 4%; P < 0.05; n = 3–5, unpaired t-test). -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

Rattlesnake Envenomation

Rattlesnake Bite Reviewers: Shawn M. Varney, Authors: Laura Morrison, MD / Ryan Chuang, MD MD Target Audience: Emergency Medicine Residents (junior and senior level postgraduate learners), Medical Students Primary Learning Objectives: 1. Recognize signs and symptoms of a venomous snakebite. 2. Recognize the indications for antivenom administration. 3. Recognize potentially dangerous complications of a snakebite and antivenom administration. Secondary Learning Objectives: detailed technical/behavioral goals, didactic points 1. Obtain medication history and evaluate for use of anticoagulant medications 2. Discuss importance of reevaluation of local effects 3. Describe the importance of removing tourniquets that may have been placed prior to arrival in ED 4. Describe the types of toxicity that can result from rattlesnake envenomation Critical actions checklist: 1. Obtain peripheral IV access (in contralateral arm) 2. Order coagulation studies (CBC, platelets, INR, fibrinogen) 3. Administer antivenom 4. Stop antivenom infusion when anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction to antivenom develops 5. Provide volume resuscitation for anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction 6. Administer medications for anaphylaxis 7. Consult Poison Center/Toxicologist 8. Admit to the MICU Environment: Emergency Department treatment area 1. Room Set Up – ED critical care area a. Manikin Set Up – Mid or high fidelity simulator b. Props – Standard ED equipment 2. Distractors – ED noise, alarming monitor For Examiner Only CASE SUMMARY SYNOPSIS OF HISTORY/ Scenario Background This is a case of a 32-year-old man who is brought to the emergency department reporting a snakebite by a prairie rattlesnake while working in the local zoo that afternoon. He reports severe pain at the site and progressive swelling up his arm since the bite 2-3 hours ago. -

EMS DIVISION 24.1 Rev. 05/14/2021 PROTOCOL 24 ENVENOMATION, BITES, and STINGS

PROTOCOL 24 ENVENOMATION, BITES, AND STINGS A. North American Pit Vipers B. Coral Snake Bites C. Exotic Snakes D. Brown Recluse Spider Bites E. Black Widow F. Scorpion Stings G. Marine Animal Envenomation H. Marine Animal Stings General Care EMR/BLS 1. Initial Assessment/Care Protocol 1. 2. Attempt to identify the insect, reptile, or animal that caused the injury if it is safe to do so. If unknown or it is a known venomous reptile bite or spider bite, have the FAO contact the Anti-Venom unit. 3. Be alert for the development of any anaphylactic reaction and treat according to the Systemic Reaction Protocol 17. 4. Immobilize the affected area. Keep the patient calm. 5. Remove and secure in a safe location any rings, bracelets, jewelry, etc. that may be in the injured area before swelling becomes too great. 6. Do not apply tourniquets, cold packs, make incisions around the area, or attempt to suction. 7. If unable to contact an Anti-Venom unit, contact the Poison Control Center, 1-800-222-1222 for assistance in managing specific envenomation. Top EMS DIVISION 24.1 Rev. 05/14/2021 PROTOCOL 24 ENVENOMATION, BITES, AND STINGS A. North American Pit Vipers Includes rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths. EMR/BLS 1. For any known or suspected bite, refer to Antivenin Bank Procedure 33. Evaluate for specific signs/symptoms: a) Distinct "fang marks" or puncture wounds. b) Swelling and pain at the site. c) Weakness, nausea, and vomiting. d) Paresthesia, fasciculations. e) Numbness and tingling around the face and head. f) Metallic taste, change in taste sensation. -

Medicines/Pharmaceuticals of Animal Origin V3.0 November 2020

Medicines/pharmaceuticals of animal origin V3.0 November 2020 Medicines/pharmaceuticals of animal origin - This guideline provides information for all clinical staff within Hospital and Health Services (HHS) on best practice for avoidance of issues related to animal products. Medicines/pharmaceuticals of animal origin - V3.0 November 2020 Published by the State of Queensland (Queensland Health), November 2020 This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2020 You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the State of Queensland (Queensland Health). For more information contact: Medication Services Queensland, Queensland Health, GPO Box 48, Brisbane QLD 4001, email [email protected] An electronic version of this document is available at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/147507/qh-gdl-954.pdf Disclaimer: The content presented in this publication is distributed by the Queensland Government as an information source only. The State of Queensland makes no statements, representations or warranties about the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any information contained in this publication. The State of Queensland disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation for liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs you might incur as a result of the information being inaccurate -

Snake Venom Detection Kit (SVDK)

SVDK Template In non-urgent situations, serum or plasma may also be used. Other samples such as lymphatic fluid, tissue fluid or extracts may 8. Reading Colour Reactions be used. • Place the test strip on the template provided over page and observe each well continuously over the next 10 minutes whilst the colour develops. Any test sample used in the SVDK must be mixed with Yellow Sample Diluent (YSD-yellow lid), prior to introduction into the The first well to show visible colour, not including the positive control well, is assay. Samples mixed with YSD should be clearly labelled with the patient’s identity and the type of sample used. The volume of diagnostic of the snake’s venom immunotype – see interpretation below. YSD in each sample vial is sufficient to allow retesting of the sample or referral to a reference laboratory for further investigation. Well 1 Tiger Snake Immunotype Snake Venom Detection Kit (SVDK) Note: Strict adherence to the 10 minute observation period after addition of Tiger Snake Antivenom Indicated Detection and Identification of Snake Venom SAMPLE PREPARATION the Chromogen and Peroxide Solutions is essential. Slow development of 1. Prepare the Test Sample. colour in one or more wells after 10 minutes should not be interpreted ENZYME IMMUNOASSAY METHOD • Any test sample used in the SVDK must be mixed with Yellow Sample Diluent (YSD-yellow lid), prior to introduction as positive detection of snake venom. Well 2 Brown Snake Immunotype into the assay. INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS Brown Snake Antivenom Indicated Note: There is enough YSD in one vial to perform two snake venom detection tests. -

First Reported Case of Thrombocytopenia from a Heterodon Nasicus Envenomation T

Toxicon 157 (2019) 12–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Case report First reported case of thrombocytopenia from a Heterodon nasicus envenomation T ∗ Nicklaus Brandehoffa,c, , Cara F. Smithb, Jennie A. Buchanana, Stephen P. Mackessyb, Caitlin F. Bonneya a Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center – Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, CO, USA b School of Biological Sciences, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO, USA c University of California, San Francisco-Fresno, Fresno, CA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Context: The vast majority of the 2.5 million annual worldwide venomous snakebites are attributed to Viperidae Envenomation or Elapidae envenomations. Of the nearly 2000 Colubridae species described, only a handful are known to cause Colubridae medically significant envenomations. Considered medically insignificant, Heterodon nasicus (Western Hognose Heterodon nasicus Snake) is a North American rear-fanged colubrid common in the legal pet trading industry. Previously reported cases of envenomations describe local pain, swelling, edema, and blistering. However, there are no reported cases of systemic or hematologic toxicity. Case details: A 20-year-old female sustained a bite while feeding a captive H. nasicus causing local symptoms and thrombocytopenia. On day three after envenomation, the patient was seen in the emergency department for persistent pain, swelling, and blistering. At that time, she was found to have a platelet count of 90 × 109/L. Previous routine platelet counts ranged from 315 to 373 × 109/L during the prior two years. Local symptoms peaked on day seven post envenomation. Her local symptoms and thrombocytopenia improved on evaluation four months after envenomation.