Snakebite: the World's Biggest Hidden Health Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

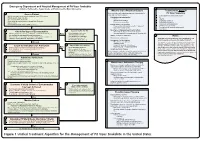

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

![Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0546/bites-and-stings-poisonous-animals-and-plants-720546.webp)

Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]

Poisonous animals and plants Dr Tim Healing Dip.Clin.Micro, DMCC, CBIOL, FZS, FRSB Course Director, Course in Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London Faculty of Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Animal and plant toxins • In most instances the numbers of people affected will be small • There are a few instances where larger numbers may be involved – mainly due to food-borne toxins Poisonous species (N.B. Venomous species use poisons for attack, poisonous animals and plants for passive defence) Venomous and poisonous animals – Reptiles (snakes) – Amphibians (dart frogs) – Arthropods (scorpions, spiders, wasps, bees, centipedes) – Aquatic animals (fish, jellyfish, octopi) Poisonous plants – Contact stinging (nettles, poison ivy, algae) – Poisonous by ingestion (fungi, berries of some plants) – Some algae Snakes Venomous Snakes • About 600 species of snake are venomous (ca. 25% of all snake species). Four main groups: – Elapidae (elapids). Mambas, Cobras, King cobras, Kraits, Taipans, Sea snakes, Brown snakes, Coral snakes. – Viperidae (viperids). True vipers and pit vipers (including Rattlesnakes, Copperheads and Cottonmouths) – Colubridae (colubrids). Mostly harmless, but includes the Boomslang – Atractaspididae (atractaspidids). Burrowing asps, Mole vipers, Stiletto snakes. Geographical distribution • Elapidae: – On land, worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, except in Europe. – Sea snakes occur in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific • Viperidae: – The Americas, Africa and Eurasia. • Boomslangs -

Venom Week 2012 4Th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous

17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins & Venom Week 2012 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012 1 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction 01 Scientific Organizing Committee 02 Local Organizing Committee / Sponsors / Co-Chairs 02 Welcome Messages 04 Governor’s Proclamation 08 Meeting Program 10 Sunday 13 Monday 15 Tuesday 20 Wednesday 26 Thursday 30 Friday 36 Poster Session I 41 Poster Session II 47 Supplemental program material 54 Additional Abstracts (#298 – #344) 61 International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis 99 2 Introduction Welcome to the 17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology (IST), held jointly with Venom Week 2012, 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous, in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012. This is a supplement to the special issue of Toxicon. It contains the abstracts that were submitted too late for inclusion there, as well as a complete program agenda of the meeting, as well as other materials. At the time of this printing, we had 344 scientific abstracts scheduled for presentation and over 300 attendees from all over the planet. The World Congress of IST is held every three years, most recently in Recife, Brazil in March 2009. The IST World Congress is the primary international meeting bringing together scientists and physicians from around the world to discuss the most recent advances in the structure and function of natural toxins occurring in venomous animals, plants, or microorganisms, in medical, public health, and policy approaches to prevent or treat envenomations, and in the development of new toxin-derived drugs. -

Myths Surrounding Snakes

MYTHS SURROUNDING SNAKES MYTH 1: Bites from baby venomous snakes are more dangerous than those from adults because they always deliver a full dose of venom. The legend goes that young snakes have not yet learned how to control the amount of venom they inject. They are therefore more dangerous than adult snakes, which will restrict the amount of venom they use in a bite or “dry bite”. This is simply untrue and all the evidence points towards bites from adults being more severe. Tests have shown that juvenile snakes can control their venom just as much as adults. Furthermore lets consider the following factors: adults have significantly larger fangs to deliver their venom and considerably more venom available than a juvenile. Therefore if a juvenile has venom glands only big enough to hold a 2ml of venom compared to an adult that can hold 30ml or more, then the bite from an adult will always have the potential to be more severe. I presume the reason this myth came into existence was to dissuade people from having a carefree attitude towards the potential dangers of a juvenile snake. The moral of the story is to treat every snake as a potentially dangerous and never expose your self to a situation where a snake of any size can bite you. MYTH 2: If you see a snake they’ll always be more Although it is possible to see more than one snake, for the most part this statement is untrue. Snakes are solitary animals for most of their lives so generally you will only ever encounter individuals. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “Pit Vipers” Whose Fangs Fold up Against the Roof of Their Mouth, Such As Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, and Cottonmouths

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “pit vipers” whose fangs fold up against the roof of their mouth, such as rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths COPPERHEAD—Agkistrodon contortrix Uncommon to common. Copperheads are found in wet wooded areas, high areas in swamps, and mountainous habitats, although they may be encountered occasionally in most terrestrial habitats. Adults usually are 2 to 3 ft. long. Their general appearance is light brown or pinkish with darker, saddle-shaped crossbands. The head is solid brown. Their leaf-pattern camouflage permits copperheads to be sit- Juvenile copper- heads and-wait predators, concealed not only from their prey but also from their enemies. Copperheads feed on mice, small birds, lizards, snakes, amphibians, and insects, especially cicadas. Like young cottonmouths, baby copperheads have a bright yellow tail that is used to lure small prey animals. 0123ft. Heat-sensing “pit” characteristic of pit vipers CANEBRAKE OR TIMBER RATTLESNAKE—Crotalus horridus Mountain form Common. This species occupies a wide diversity of terrestrial habitats, but is found most frequently in deciduous forests and high ground in swamps. Heavy-bodied adults are usually 3 to 4, and occasionally 5, ft. long. Their basic color is gray with black crossbands that usually are chevron-shaped. Timber rattlesnakes feed on various rodents, rabbits, and occasionally birds. These rattlesnakes are generally passive if not disturbed or pestered in some way. When a rattlesnake is Coastal plain form encountered, the safest reaction is to back away--it will not try to attack you if you leave it alone. 012345 ft. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE— Crotalus adamanteus Rare. This rattlesnake is found in both wet and dry terrestrial habitats including palmetto stands, pine woods, and swamp margins. -

Clinical Effects and Antivenom Use for Snake Bite Victims Treated at Three US Hospitals in Afghanistan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Army Research U.S. Department of Defense 2013 Clinical Effects and Antivenom Use for Snake Bite Victims Treated at Three US Hospitals in Afghanistan Jason D. Heiner University of Washington - Seattle Campus, [email protected] Vikhyat S. Bebarta San Antonio Military Medical Center Shawn M. Varney San Antonio Military Medical Center Jason D. Bothwell Madigan Army Medical Center Aaron J. Cronin Womack Army Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch Heiner, Jason D.; Bebarta, Vikhyat S.; Varney, Shawn M.; Bothwell, Jason D.; and Cronin, Aaron J., "Clinical Effects and Antivenom Use for Snake Bite Victims Treated at Three US Hospitals in Afghanistan" (2013). US Army Research. 198. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch/198 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Army Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WILDERNESS & ENVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE, ], ]]]–]]] (2013) BRIEF REPORT Clinical Effects and Antivenom Use for Snake Bite Victims Treated at Three US Hospitals in Afghanistan Jason D. Heiner, MD; Vikhyat S. Bebarta, MD; Shawn M. Varney, MD; Jason D. Bothwell, MD; Aaron J. Cronin, PA-C From the University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Dr Heiner); the San Antonio Military Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, TX (Drs Heiner, Bebarta, and Varney); the Madigan Army Medical Center, Joint Base Lewis-McCord, WA (Dr Bothwell); and the Womack Army Medical Center, Fort Bragg, NC (Mr Cronin). -

Bitis Arietans) Venom, and Their Neutralization by Antivenom

Toxins 2014, 6, 1586-1597; doi:10.3390/toxins6051586 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article In Vitro Toxic Effects of Puff Adder (Bitis arietans) Venom, and Their Neutralization by Antivenom Steven Fernandez 1, Wayne Hodgson 1, Janeyuth Chaisakul 2, Rachelle Kornhauser 1, Nicki Konstantakopoulos 1, Alexander Ian Smith 3 and Sanjaya Kuruppu 3,* 1 Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Building 13E, Wellington Road, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (R.K.); [email protected] (N.K.) 2 Department of Pharmacology, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Monash University, Building 77, Wellington Road, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +61-3-9902-9372; Fax: + 61-3-9902-9500. Received: 24 November 2013; in revised form: 6 April 2014 / Accepted: 4 May 2014 / Published: 19 May 2014 Abstract: This study investigated the in vitro toxic effects of Bitis arietans venom and the ability of antivenom produced by the South African Institute of Medical Research (SAIMR) to neutralize these effects. The venom (50 µg/mL) reduced nerve-mediated twitches of the chick biventer muscle to 19% ± 2% of initial magnitude (n = 4) within 2 h. This inhibitory effect of the venom was significantly attenuated by prior incubation of tissues with SAIMR antivenom (0.864 µg/µL; 67% ± 4%; P < 0.05; n = 3–5, unpaired t-test). -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation.