Venomous Snakebites in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What You Should Know About Rattlesnakes

Rattlesnakes in The Rattlesnakes of Snake Bite: First Aid WHAT San Diego County Parks San Diego County The primary purpose of the rattlesnake’s venomous bite is to assist the reptile in securing The Rattlesnake is an important natural • Colorado Desert Sidewinder its prey. After using its specialized senses to find YOU SHOULD element in the population control of small (Crotalus cerastes laterorepens) its next meal, the rattlesnake injects its victim mammals. Nearly all of its diet consists of Found only in the desert, the sidewinder prefers with a fatal dose of venom. animals such as mice and rats. Because they are sandy flats and washes. Its colors are those of KNOW ABOUT so beneficial, rattlesnakes are fully protected the desert; a cream or light brown ground color, To prevent being bitten, the best advice is to leave within county parks. with a row of brown blotches down the middle snakes alone. RATTLESNAKES If you encounter a rattlesnake while hiking, of the back. A hornlike projection over each eye Most bites occur when consider yourself lucky to have seen one of separates this rattlesnake from the others in our area. Length: 7 inches to 2.5 feet. someone is nature’s most interesting animals. If you see a trying to pick rattlesnake at a campsite or picnic area, please up a snake, inform the park rangers. They will do their best • Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake (Crotalus mitchelli pyrrhus) tease it, or kill to relocate the snake. it. If snakes are Most often found in rocky foothill areas along the provided an coast or in the desert. -

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’S Uncanny Mountain Denizen

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’s Uncanny Mountain Denizen photo-Steve Shaffer by Christopher A. Urban breath, “the only good snake is a dead snake.” Others are Chief, Natural Diversity Section fascinated or drawn to the critter for its perceived danger- ous appeal or unusual size compared to other Pennsylva- Who would think that in one of the most populated nia snakes. If left unprovoked, the timber rattlesnake is states in the eastern U.S., you could find a rattlesnake in actually one of Pennsylvania’s more timid and docile the mountains of Penn’s Woods? As it turns out, most snake species, striking only when cornered or threatened. timber rattlesnakes in Pennsylvania are found on public Needless to say, the Pennsylvania timber rattlesnake is an land above 1,800 feet elevation. Of the three venomous intriguing critter of Pennsylvania’s wilderness. snakes that occur in Pennsylvania, most people have heard about this one. It strikes fear in the hearts of some Description and elicits fascination in others. When the word “rattler” The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) is a large comes up, you may hear some folks grumble under their (up to 74 inches), heavy-bodied snake of the pit viper www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater, January-February 2004 17 family (Viperidae). This snake has transverse “V”-shaped or chevronlike dark bands on a gray, yellow, black or brown body color. The tail is completely black with a rattle. The head is large, flat and triangular, with two thermal-sensitive pits between the eyes and the nostrils. The timber rattlesnake’s head color has two distinct color phases. -

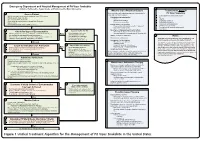

Snake Bite Protocol

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020 Timber rattlesnakes live in the blufflands of southeastern Minnesota. They are not found anywhere else in the state. They can be distinguished from nonvenomous snakes by a pronounced off white rattle at the end of a black tail; by their head, which is solid brown/tan, triangular shaped, and noticeably larger than their slender neck; and by the dark, black bands or chevrons running across their body. The bands often resemble the black stripe on the cartoon character Charlie Brown’s shirt. The question that often arises when the word rattlesnake comes up is, “What if one bites me?” The likelihood of being bitten by a rattlesnake is quite small. Timber rattlesnakes are generally very docile snakes and typically bite as a last resort. Instead, its instincts are to avoid danger by retreating to cover or by hiding using its camouflage coloration to blend into its surroundings. If cornered and provoked, a timber rattlesnake may respond aggressively. It will usually rattle its tail to let you know it is getting agitated. The snake may even puff itself up to appear bigger. Upon further provocation, the snake may bluff strike, where it lunges out, but doesn’t open its mouth or it may strike with an open mouth. Because venom is costly for a rattlesnake to produce, and you are not considered food, a snake often will not actively inject venom when it bites. In fact, nearly half of all timber rattlesnake bites to humans contain little to no venom, commonly referred to as dry or medically insignificant bites. -

Species Assessment for the Midget Faded Rattlesnake (Crotalus Viridis Concolor)

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR THE MIDGET FADED RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS CONCOLOR ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 AMBER TRAVSKY AND DR. GARY P. BEAUVAIS 1 Real West Natural Resource Consulting, 1116 Albin Street, Laramie, WY 82072; (307) 742-3506 2 Director, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Dept. 3381, 1000 E. University Ave., Laramie, WY 82071; (307) 766-3023 prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming October 2004 Travsky and Beauvais – Crotalus viridus concolor October 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 2 Morphological Description........................................................................................................... 3 Taxonomy and Distribution ......................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Requirements ................................................................................................................. 6 General ............................................................................................................................................6 Area Requirements..........................................................................................................................7 -

![Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0546/bites-and-stings-poisonous-animals-and-plants-720546.webp)

Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]

Poisonous animals and plants Dr Tim Healing Dip.Clin.Micro, DMCC, CBIOL, FZS, FRSB Course Director, Course in Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London Faculty of Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Animal and plant toxins • In most instances the numbers of people affected will be small • There are a few instances where larger numbers may be involved – mainly due to food-borne toxins Poisonous species (N.B. Venomous species use poisons for attack, poisonous animals and plants for passive defence) Venomous and poisonous animals – Reptiles (snakes) – Amphibians (dart frogs) – Arthropods (scorpions, spiders, wasps, bees, centipedes) – Aquatic animals (fish, jellyfish, octopi) Poisonous plants – Contact stinging (nettles, poison ivy, algae) – Poisonous by ingestion (fungi, berries of some plants) – Some algae Snakes Venomous Snakes • About 600 species of snake are venomous (ca. 25% of all snake species). Four main groups: – Elapidae (elapids). Mambas, Cobras, King cobras, Kraits, Taipans, Sea snakes, Brown snakes, Coral snakes. – Viperidae (viperids). True vipers and pit vipers (including Rattlesnakes, Copperheads and Cottonmouths) – Colubridae (colubrids). Mostly harmless, but includes the Boomslang – Atractaspididae (atractaspidids). Burrowing asps, Mole vipers, Stiletto snakes. Geographical distribution • Elapidae: – On land, worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, except in Europe. – Sea snakes occur in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific • Viperidae: – The Americas, Africa and Eurasia. • Boomslangs -

Venom Week 2012 4Th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous

17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins & Venom Week 2012 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012 1 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction 01 Scientific Organizing Committee 02 Local Organizing Committee / Sponsors / Co-Chairs 02 Welcome Messages 04 Governor’s Proclamation 08 Meeting Program 10 Sunday 13 Monday 15 Tuesday 20 Wednesday 26 Thursday 30 Friday 36 Poster Session I 41 Poster Session II 47 Supplemental program material 54 Additional Abstracts (#298 – #344) 61 International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis 99 2 Introduction Welcome to the 17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology (IST), held jointly with Venom Week 2012, 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous, in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012. This is a supplement to the special issue of Toxicon. It contains the abstracts that were submitted too late for inclusion there, as well as a complete program agenda of the meeting, as well as other materials. At the time of this printing, we had 344 scientific abstracts scheduled for presentation and over 300 attendees from all over the planet. The World Congress of IST is held every three years, most recently in Recife, Brazil in March 2009. The IST World Congress is the primary international meeting bringing together scientists and physicians from around the world to discuss the most recent advances in the structure and function of natural toxins occurring in venomous animals, plants, or microorganisms, in medical, public health, and policy approaches to prevent or treat envenomations, and in the development of new toxin-derived drugs. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Snakebite and Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2013

Guideline Ministry of Health, NSW 73 Miller Street North Sydney NSW 2060 Locked Mail Bag 961 North Sydney NSW 2059 Telephone (02) 9391 9000 Fax (02) 9391 9101 http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/ space space Snakebite and Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2013 - Third Edition space Document Number GL2014_005 Publication date 17-Mar-2014 Functional Sub group Clinical/ Patient Services - Critical care Clinical/ Patient Services - Medical Treatment Summary Revised clinical resource document which provides information and advise on the management of patients with actual or suspected snakebite or spiderbite, and the appropriate levels, type and location of stored antivenom in NSW health facilities. These are clinical guidelines for best clinical practice which are not mandatory but do provide essential clinical support. Replaces Doc. No. Snakebite & Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2007 - NSW [GL2007_006] Author Branch Agency for Clinical Innovation Branch contact Agency for Clinical Innovation 9464 4674 Applies to Local Health Districts, Board Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Chief Executive Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Specialty Network Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Affiliated Health Organisations, Community Health Centres, Government Medical Officers, NSW Ambulance Service, Ministry of Health, Private Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, Public Health Units, Public Hospitals Audience Clinicial Nursing, Medical, Allied Health Staff, Administration, ED, Intensive Care Units Distributed to Public Health System, Divisions of General Practice, Government Medical Officers, Ministry of Health, Private Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, Tertiary Education Institutes Review date 17-Mar-2019 Policy Manual Patient Matters File No. 12/4133 Status Active Director-General FIVE Spiderbite Guidelines for Assessment and Management Introduction Red-back spider envenoming or latrodectism is Specific features of funnel-web and red back bite are characterised by severe local or regional pain associated discussed below. -

Canebrake (A.K.A. Timber) Rattlesnake

Canebrake (a.k.a. Timber) Rattlesnake Crotalus horridus Upland Snake Species Profile Venomous Range and Appearance: This species ranges from New England through North Florida, and westward to central Texas and southern Minnesota. In the northern portion of their range, they are referred to as timber rattlesnakes and in the southern portion of the range they are often called canebrake rattlesnakes. Both names refer to the same species, although there are color differences that vary latitudinally. With the exception of nearly jet-black animals which occur in the Northeast, this species has a series of brown chevrons that extend the length of the body. They have keeled scales and the base color can be brown, greenish- Name Game gray, or creamy-yellow. Individuals in the southeast The genus, Crotalus, roughly translates to “rattle”. may have a pink hue. Canebrakes often have a The species epithet, horridus, means “frightful”. brown stripe that runs down the middle of their back, a characteristic not present in northern populations. Neonates (newborn snakes) have Natural History: Canebrake rattlesnakes are pit- similar color patterns as adults. Exceptionally large vipers that belong to the family Viperidae. They are canebrakes can measure over 8 feet, but most ambush predators and may spend several weeks in adult animals range between 4 to 6 feet in length. the same location waiting to strike at a potential meal. Adults typically feed on rodents, such as chipmunks, rats, mice, voles, and squirrels. In Rattlesnake Myth addition to sight and smell, rattlesnakes have a Rattlesnakes grow a new rattle segment loreal pit that allows them to detect infrared during each shed cycle.