Obliterative Bronchiolitis with Atypical Features: CT Scan and Necropsy Findings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management

THIEME Original Research 125 Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management Shibu George1 Sandeep Suresh2 1 Department of ENT, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, India Address for correspondence ShibuGeorge,MS,DNB,Charivukalayil 2 Department of ENT, Little Flower Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India (House), Ettumanoor, Kottayam 686631, Kerala, India (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:125–130. Abstract Introduction Vocal cord dysfunction is characterized by unintentional paradoxical vocal cord movement resulting in abnormal inappropriate adduction, especially during inspiration; this predominantly manifests as unresponsive asthma or unexplained stridor. It is prudent to be well informed about the condition, since the primary presentation may mask other airway disorders. Objective This descriptive study was intended to analyze presentations of vocal cord dysfunction in a tertiary care referral hospital. The current understanding regarding the pathophysiology and management of the condition were also explored. Methods A total of 27 patients diagnosed with vocal cord dysfunction were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, presentations, associations and examination findings. The mechanism of causation, etiological factors implicated, diagnostic considerations and treatment options were evaluated by analysis of the current literature. Results Therewasastrongfemalepredilection noted among the study population (n ¼ 27), which had a mean age of 31. The most common presentations were stridor Keywords (44%) and refractory asthma (41%). Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease was the most ► Vocal Cord common association in the majority (66%) of the patients, with a strong overlay of Dysfunction anxiety, demonstrable in 48% of the patients. ► paradoxical vocal Conclusion Being aware of the condition is key to avoid misdiagnosis in vocal cord cord motion dysfunction. -

Middle Airway Obstructiondit May Be Happening Under Our Noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1

Thorax Online First, published on July 19, 2012 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 Chest clinic OPINION Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 on 19 July 2012. Downloaded from Middle airway obstructiondit may be happening under our noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1 < Additional materials are ABSTRACT for this conceptual error to be refuted.2 The virus is published online only. To view Background Lower airway obstruction has evolved to now understood to spread from nose to lung, and these files please visit the denote pathologies associated with diseases of the lung, appropriate recognition of the close association journal online (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/ whereas, conditions proximal to the lung embody upper between upper and lower airway pathologies has thoraxjnl-2012-202221/content/ airway obstruction. This approach has disconnected had positive outcomes. An example is novel strat- early/recent). diseases of the larynx and trachea from the lung, and egies that may not be able to prevent colds, but 1Lung and Sleep Medicine, removed the ‘middle airway’ from the interest and that could ameliorate virus asthma exacerbations Monash University and Hospital involvement of respiratory physicians and scientists. through the use of inhaled interferon.3 and Monash Institute of Medical However, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction Accumulating evidence suggests that the middle Research (MIMR), Melbourne, of this anatomical region may be a key component of Australia airway plays a key role in airway obstruction either 2Respiratory Medicine, Imperial overall airway obstruction, either independently or in independently or with coexisting lung disease. -

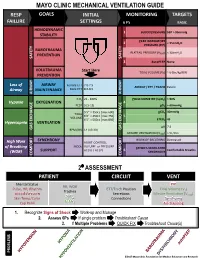

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Exercise-induced Laryngeal Obstruction Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is a breathing problem that affects people during exercise. EILO is defined by inappropriate narrowing of the upper airway at the level of the vocal cords (glottis) and/or supraglottis (above the vocal cords). This can make it hard to get air into your lungs during exercise and cause a noisy breathing that can be frightening. EILO has also been called vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) or paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM). Most people with EILO only have symptoms when they Common signs and symptoms of EILO exercise, those some people may have the problem at During (or immediately after) high-intensity exercise, other times as well. (See ATS Patient Information Series with EILO you may experience: fact sheet ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction/Vocal Cord ■■ Profound shortness of breath or breathlessness Dysfunction’) ■■ Noisy breathing, particularly when breathing in Where are the vocal cords and what do they do? (stridor, gasping, raspy sounds, or “wheezing”) Your vocal cords are located in your upper airway or ■■ A feeling of choking or suffocation that can be scary larynx. Your supraglottic structures (including your ■■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Feeling like there is a lump in the throat arytenoid cartilages and epiglottis) are located above the ■■ Throat or chest tightness vocal cords and are part of your larynx. The larynx is often called the voice box and is deep in your throat. When These symptoms often come on suddenly during you speak, the vocal cords vibrate as you breathe out, exercise, and are typically quite noticeable or concerning to people around you as well. -

Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Workers Exposed to Food Flavorings

HEALTH ALERT Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Workers Exposed to Food Flavorings Recently, several investigations have identified clusters of workers diagnosed with bronchiolitis obliterans (commonly referred to as “popcorn workers’ lung” and “flavorings-related lung disease”), a form of fixed, irreversible airway obstruction, after exposure to mixtures of butter flavoring chemicals. Evaluations of these workers revealed high rates of both severe respiratory symptoms and significantly compromised lung function.1 These investigations concluded that there is a risk for occupational lung disease in workers with inhalation exposure to butter flavoring chemicals.2 Other investigations have also shown that workers that use or manufacture certain food flavoring additives have developed similar health problems. Diacetyl and Other Food Flavorings Used in Food and Flavoring Manufacturing Food flavorings can be either natural or manmade. Some are comprised of only one ingredient, but others are complex mixtures of several substances. Diacetyl is a chemical used in the manufacture of butter flavoring and other food flavorings and is the suspected cause of several cases of bronchiolitis obliterans in workers. During the manufacturing process, workers may be exposed to food flavorings in the form of vapors, dusts, or sprays. There are many different types of food flavorings and most have not been tested for respiratory toxicity. However, recent animal studies of diacetyl exposure conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) have shown an association between diacetyl and fixed obstructive pulmonary disease. What are the health effects associated with flavorings-related lung disease? Exposure to certain airborne food flavorings is associated with higher rates of respiratory symptoms such as coughing, shortness of breath, fatigue, and difficulty breathing with exertion or exercise. -

Focus on Bronchiectasis/COPD Overlap: an Under-Recognized but Critically Important Condition

Focus on Bronchiectasis/COPD Overlap: An Under-Recognized But Critically Important Condition Gary Hansen, PhD Former “Orphan Disease” Grows in Recognition Recognizing • Chronic productive cough Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB)1 is an important Bronchiectasis2 disease that remains largely unknown. Once thought to be a rare • Chronic mucus hypersecretion “orphan” condition—merely the aftermath of infectious diseases • Chronic antibiotic use that are now readily treated—emerging evidence now shows that NCFB is far more common than originally believed and is closely • Frequent hospitalizations associated with another better known major respiratory health • Reduced quality of life threat—COPD.3 Defined as the thickening and enlargement of the airways resulting from chronic inflammation, bronchiectasis damages normal airway clearance mechanisms and results in the The process is irreversible and there is no known cure— accumulation of excess secretions. As a result, patients face fortunately, appropriate care can substantially improve the chronic cough, excess sputum production, and a recurring cycle lives of affected patients. of hospitalizations.2 Appropriate diagnosis and treatment are key to improving quality of life and reducing the need for expensive While bronchiectasis may be found at any age, it is most often medical care. Specifically, airway clearance therapy directly a disease of middle-age and older. The profile of a patient with addresses the problem of purulent sputum retained in the bronchiectasis is in many ways similar to that of chronic airways and by “emptying the Petri dish” can help to reduce the bronchitis.8 Affected patients often have a chronic productive risk of future exacerbations without risking exposure to the cough for more than three months of the year along with negative effects of long-term orWhile rotating bronchiectasis antibiotics. -

Respiratory Distress

Respiratory Distress National Pediatric Nighttime Curriculum Written by Liane Campbell, MD Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford University Learning Objectives Review the initial assessment of patient in respiratory distress Review management of specific causes of respiratory distress Upper airway obstruction Lower airway obstruction Lung tissue disease Disordered control of breathing During a busy night, you get the following page: FYI: Sally, a 2 year old with PNA had a desat to 88% while on 4L NC. What do you do next? What initial management steps would you take? How do you initially assess a patient in respiratory distress? Initial Assesment Rapid assessment Quickly determine severity of respiratory condition and stabilize child Respiratory distress can quickly lead to cardiac compromise Airway Support or open airway with jaw thrust Suction and position patient Breathing Provide high concentration oxygen Bag mask ventilation Prepare for intubation Administer medication ie albuterol, epinephrine Circulation Establish vascular access: IV/IO History and Physical Exam History Physical Exam Trauma Mental status Change in voice Position of comfort Onset of symptoms Nasal flaring Associated symptoms Accessory muscle use Exposures Respiratory rate and Underlying medical pattern conditions Auscultation for abnormal breath sounds What initial studies would you get for a patient in respiratory distress? Initial studies Pulse oximetry May be difficult in agitated patient May be falsely decreased in very anemic -

PEDIATRIC VIRAL BRONCHIOLITIS ALGORITHM: Emergency Department Bronchiolitis Management

CLINICAL PATHWAY PEDIATRIC VIRAL BRONCHIOLITIS ALGORITHM: Emergency Department Bronchiolitis Management Triage/Bedside RN: Vital signs, pulse oximetry, blood pressure, weight. Suction as needed beginning with bulb or nasal aspirator, advancing to deep/mechanical suction as needed for persistent respiratory distress. Provider: History and physical exam, evaluate for red flags and comorbidities Inclusion criteria: • Age 1 mo to < 2 yrs Previously healthy patient age 1-23 months • Principle diagnosis: presenting to ED/UC with viral bronchiolitis uncomplicated bronchiolitis Exclusion criteria: • Patients requiring PICU admission Assess patient and assign severity • Patients with underlying (Table 1) respiratory illnesses • Recurrent wheezing • Immunodeficiency Mild Moderate Severe • Assess WOB and O2 requirement Noninvasive • Treat ABCs suctioning (bulb/nasal • Deep Suction aspirator) PRN; • Consider alternative advance to deep diagnosis • Mildly increased WOB • Mildly increased WOB suctioning for respiratory • O2 req. </= 0.5L • O2 req. > 0.5L distress unrelieved by • No tachypnea for age • Symptoms • Symptoms not noninvasive • Pulse ox >/= 90% RA • manageable with bulb manageable with bulb O2 PRN if SpO2 <88% Reassess • Feeding well • Antipyretics PRN suction only (or nose suction only (or nose • Consider PO Trial (Table 1) frida if available) frida if available) Bulb suction or Reassess Assess qualification for Severe NoseFrida teaching Yes (Table 1) Home O2 Anticipatory guidance (see protocol) DC home Moderate • Adjust O2 flow PRN for -

Risk Factors for Diagnostic Delay in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Nils Hoyer1* , Thomas Skovhus Prior2, Elisabeth Bendstrup2, Torgny Wilcke1 and Saher Burhan Shaker1

Hoyer et al. Respiratory Research (2019) 20:103 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1076-0 RESEARCH Open Access Risk factors for diagnostic delay in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Nils Hoyer1* , Thomas Skovhus Prior2, Elisabeth Bendstrup2, Torgny Wilcke1 and Saher Burhan Shaker1 Abstract Background: Surveys and retrospective studies of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) have shown a significant diagnostic delay. However, the causes and risk factors for this delay are not known. Methods: Dates at six time points before the IPF diagnosis (onset of symptoms, first contact to a general practitioner, first hospital contact, referral to an interstitial lung disease (ILD) centre, first visit at an ILD centre, and final diagnosis) were recorded in a multicentre cohort of 204 incident IPF patients. Based on these dates, the delay was divided into specific patient-related and healthcare-related delays. Demographic and clinical data were used to determine risk factors for a prolonged delay, using multivariate negative binomial regression analysis. Results: The median diagnostic delay was 2.1 years (IQR: 0.9–5.0), mainly attributable to the patients, general practitioners and community hospitals. Male sex was a risk factor for patient delay (IRR: 3.84, 95% CI: 1.17–11.36, p = 0.006) and old age was a risk factor for healthcare delay (IRR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06, p = 0.004). The total delay was prolonged in previous users of inhalation therapy (IRR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.40–2.88, p < 0.0001) but not in patients with airway obstruction. Misdiagnosis of respiratory symptoms was reported by 41% of all patients. -

Surgical Pathology of Non-Neoplastic Lung Disease Thomas V

SHORT COURSE Surgical Pathology of Non-Neoplastic Lung Disease Thomas V. Colby, M.D. Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic Scottsdale, Scottsdale, Arizona At inception, this course included some neoplastic Case 1: Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic lesions, but each year, the case mix was changed in Pulmonary Fibrosis response to the comments (and criticism) of the A 51-year-old man had experienced 3 to 4 years attendees. As cases were added and deleted, in the of progressive dyspnea and interstitial infiltrates as end only examples of non-neoplastic lung disease observed on chest radiographs. One week before were discussed. Of the 19 cases used during the death, there was acute worsening of his dyspnea, course of 5 years, the following 8 were selected for with some associated chills and a sore throat. At this presentation. admission, he was hypoxemic, tachypneic, and afe- brile. The clinical impression was an acute (possibly CASES 1, 2, AND 3: IDIOPATHIC INTERSTITIAL infectious) process superimposed on idiopathic PNEUMONIAS AND RELATED LESIONS pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). An open-lung biopsy was performed. The patient died 1 week later. Cultures To the clinician, there are well over 100 causes of and special stains were negative. interstitial pneumonia, but among these, there is a select subgroup that has been called the idiopathic Histologic findings interstitial pneumonias. This group has evolved The open biopsy shows subpleural scarring and from Liebow and Carrington’s (1) classic classifica- microscopic honeycombing, with associated tion of chronic interstitial pneumonias: smooth muscle metaplasia and fibroblastic foci Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (Figs. 1 and 2). -

Physiology of the Lung in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

REVIEW IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS Physiology of the lung in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Laurent Plantier1,2,3, Aurélie Cazes4,5,6, Anh-Tuan Dinh-Xuan7,8, Catherine Bancal9, Sylvain Marchand-Adam1,2,3 and Bruno Crestani5,6,10 Affiliations: 1Service de Pneumologie et Explorations Fonctionnelles Respiratoires, Hôpital Bretonneau, Tours, France. 2Université François Rabelais, Tours, France. 3CEPR/INSERM UMR1100, LabexMabImprove, Tours, France. 4AP-HP, Hôpital Bichat, Service d’Anatomie Pathologique, Paris, France. 5Université Paris Diderot, PRES Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France. 6INSERM UMR1152, LabexInflamex, Paris, France. 7AP-HP, Hôpital Cochin, Service de Physiologie-Explorations Fonctionnelles, Paris, France. 8Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France. 9AP-HP, Hôpital Bichat, Service de Physiologie-Explorations Fonctionnelles, Paris, France. 10AP-HP, Hôpital Bichat, Service de Pneumologie A, DHU FIRE, Paris, France. Correspondence: Bruno Crestani, Hôpital Bichat, Service de Pneumologie A, 45 rue Henri Huchard, 75018 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] @ERSpublications Physiological impairment in IPF is complex and involves all compartments of the respiratory system http://ow.ly/gyao30hdHUb Cite this article as: Plantier L, Cazes A, Dinh-Xuan A-T, et al. Physiology of the lung in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2018; 27: 170062 [https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0062-2017]. ABSTRACT The clinical expression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is directly related to multiple alterations in lung function. These alterations derive from a complex disease process affecting all compartments of the lower respiratory system, from the conducting airways to the lung vasculature. In this article we review the profound alterations in lung mechanics (reduced lung compliance and lung volumes), pulmonary gas exchange (reduced diffusing capacity, increased dead space ventilation, chronic arterial hypoxaemia) and airway physiology (increased cough reflex and increased airway volume), as well as pulmonary haemodynamics related to IPF. -

Managing Airway Obstruction

Managing airway obstruction Introduction commonly be related to the cause or dynamic situations that may rapidly Recognizingairwaycompromiseisafun- pathogenesisofdiseaseprocess. progressfromoneofstabilitytooneofa damental skill for junior doctors as they There are a large number of causes of threatened and compromised airway. As will frequently be first managing these airway obstruction (Table 1), and it is such early intubation is undertaken in patients.Byappreciatingthecausesofan importanttolookoutforat-riskgroupsin theseat-riskgroups. obstructedairway,treatmentwithoxygen whom airway compromise is more com- Externalcompressionfromanadjacent andanumberofsimplemanoeuvrescan mon. Patients with a reduced conscious pathology, e.g. goitre, lymphadenopathy, bedeliveredswiftly,preservingairwaypat- level are unable to clear their own secre- tumour and haematoma (e.g. post-thy- ency and passage of oxygen to the lungs tionsandcannotprotecttheirownairway. roidectomy),maybeinsidiousorrapidin forventilation.Ventilationisthemechani- AGlasgowComaScaleof8/15orbelowis onset.Inpatientswithunderlyingmalig- cal movement of air into and out of the often considered the threshold at which nancy,itisimportantforclinicianstobe respiratory system, resulting in the intubation is necessary. Patients with vigilant in identifying features suggestive exchangeofcarbondioxide. reducedconsciouslevelareatriskofaspi- ofairwaycompromise. Airwayobstructionresultsinhypoventi- ration and alveolar hypoventilation, with Airway obstruction may occur at any lation, increased work