Frequency and Causes of Combined Obstruction and Restriction Identified in Pulmonary Function Tests in Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in COPD (Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema): Morbidity and Mortality

Trends in COPD (Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema): Morbidity and Mortality Please note, this report is designed for double-sided printing American Lung Association Epidemiology and Statistics Unit Research and Health Education Division March 2013 Page intentionally left blank Table of Contents COPD Mortality, 1999-2009 COPD Prevalence, 1999-2011 COPD Hospital Discharges, 1999-2010 Glossary and References List of Tables Table 1: COPD – Number of Deaths by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 1999-2009 Figure 1: COPD – Number of Deaths by Sex, 1999-2009 Figure 2: COPD – Age-Adjusted Death Rates by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 2009 Table 2: COPD – Age-Adjusted Death Rate per 100,000 Population by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 1999- 2009 Figure 3: COPD – Deaths and Age-Adjusted Death Rate by Sex, 2009 Figure 4: COPD – Diagnosed Cases and Evidence of Impaired Lung Function Figure 5: Chronic Bronchitis – Prevalence Rates per 1,000, 2011 Table 3: Chronic Bronchitis – Number of Conditions and Prevalence Rate per 1,000 Population by Ethnic Origin, Sex and Age, 1999-2011 Figure 6: Emphysema – Prevalence Rates per 1,000, 2011 Table 4: Emphysema – Number of Conditions and Prevalence Rate per 1,000 Population by Ethnic Origin, Sex and Age, 1997-2011 Table 5: COPD – Adult Prevalence by Sex and State, 2011 Figure 8: COPD – Age-Adjusted Prevalence in Adults by State, 2011 Table 6: Characteristics Among Those Reporting a Diagnosis of COPD by State (%), 2011 Figure 9: COPD – First-Listed Hospital Discharge Rates per 10,000, 2010 Table 7: COPD – Number of First-Listed Hospital Discharges and Rate per 10,000 Population by Race, Sex and Age, 1999-2010 Figure 9: National Projected Annual Cost of COPD, 2010 Introduction Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a term which refers to a large group of lung diseases characterized by obstruction of air flow that interferes with normal breathing. -

Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease &Bronchiectasis

PLEASE CHECK Editing file BEFORE! Chronic Obstructive lung Disease & Bronchiectasis ★ Objectives: 1. Definition of the two conditions 2. Clinical and radiological diagnosis 3. Differential diagnosis 4. General outline of management 5. Create a link to 341 clinical teaching ★ Resources Used in This lecture: Davidson, Guyton and Becker step 1 lecture notes Done by: Mohammad Alkharraz Contact us at: [email protected] Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD) COPD contains two diseases which are chronic bronchitis and emphysema ■ COPD is classified under obstructive pulmonary diseases along with other (no kidding!) diseases such as asthma and bronchiectasis ■ Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are grouped together under COPD because they are both mainly caused by smoking and they usually present together. ■ Brainless pathology textbooks (Robbins) try to confuse us students with “Pink Puffers” and “Blue Bloaters”. Forget about that as it is not clinically relevant1. Let us quickly point out some points (pathology) that are relevant to each disease (chronic bronchitis and emphysema) and then we will discuss the clinical presentation, management, etc. of COPD Chronic bronchitis It is mainly a clinical diagnosis patients cough up lots of sputum for a long period of time “3 months per year for at least 2 consecutive years2” ● Pathogenesis: Cigarette smoke causes hyperplasia of mucus glands which increase the secretion of mucus → mucus plugs cause obstruction of bronchioles→ COPD Emphysema It is mainly a pathological diagnosis. ● Pathogenesis: 1. Pollutants (smoking)→ increased inflammatory mediators in the lung that destroy the lung parenchyma (trypsin and elastase) 2. We have defense mechanisms to fight these inflammatory mediators (alpha1 antitrypsin) ○ However, the amount of inflammatory mediators exceeds our ability to counteract them 3. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis As a Cause of Bronchial Asthma in Children

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;10(2):95-100. Original article Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis as a cause of bronchial asthma in children Background: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) occurs in Dina Shokry, patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. When aspergillus fumigatus spores Ashgan A. are inhaled they grow in bronchial mucous as hyphae. It occurs in non Alghobashy, immunocompromised patients and belongs to the hypersensitivity disorders Heba H. Gawish*, induced by Aspergillus. Objective: To diagnose cases of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis among asthmatic children and define the Manal M. El-Gerby* association between the clinical and laboratory findings of aspergillus fumigatus (AF) and bronchial asthma. Methods: Eighty asthmatic children were recruited in this study and divided into 50 atopic and 30 non-atopic Departments of children. The following were done: skin prick test for aspergillus fumigatus Pediatrics and and other allergens, measurement of serum total IgE, specific serum Clinical Pathology*, aspergillus fumigatus antibody titer IgG and IgE (AF specific IgG and IgE) Faculty of Medicine, and absolute eosinophilic count. Results: ABPA occurred only in atopic Zagazig University, asthmatics, it was more prevalent with decreased forced expiratory volume Egypt. at the first second (FEV1). Prolonged duration of asthma and steroid dependency were associated with ABPA. AF specific IgE and IgG were higher in the atopic group, they were higher in Aspergillus fumigatus skin Correspondence: prick test positive children than negative ones .Wheal diameter of skin prick Dina Shokry, test had a significant relation to the level of AF IgE titer. Skin prick test Department of positive cases for aspergillus fumigatus was observed in 32% of atopic Pediatrics, Faculty of asthmatic children. -

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia—Results of Treatment with Clarithromycin Versus Corticosteroids—Observational Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐResults of treatment with clarithromycin versus corticosteroidsÐObservational study Elżbieta Radzikowska1*, Elżbieta Wiatr1☯, Renata Langfort2³, Iwona Bestry3³, Agnieszka Skoczylas4, Ewa Szczepulska-Wo jcik2³, Dariusz Gawryluk1☯, Piotr Rudziński5³, Joanna Chorostowska-Wynimko6³, Kazimierz Roszkowski-Śliż1³ 1 III Department of Lung Disease National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 2 Pathology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 3 Radiology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 4 Geriatrics Department National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 5 Thoracic Surgery Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, a1111111111 Warsaw, Poland, 6 Laboratory of Molecular Diagnostics and Immunology National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland a1111111111 a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Radzikowska E, Wiatr E, Langfort R, Bestry I, Skoczylas A, Szczepulska-WoÂjcik E, et al. (2017) Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐ Background Results of treatment with clarithromycin versus Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a clinicopathological syndrome of unknown ori- corticosteroidsÐObservational study. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184739. -

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (Copd) in the Americas

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) IN THE AMERICAS KEY STATISTICS FOR THE AMERICAS An estimated 13.2 million people live with COPD (1). COPD caused over 235,000 deaths in 2010, ranking as the sixth leading cause of death (2). 7 in 10 COPD deaths are attributable to tobacco (3). In 2012, COPD was responsible for the loss of 8.3 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (3). KEY MESSAGES CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) IS A LEADING CAUSE OF MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY IN THE 1 AMERICAS, REPRESENTING AN IMPORTANT PUBLIC HEALTH CHALLENGE THAT IS BOTH PREVENTABLE AND TREATABLE. COPD is an incurable disease, characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases in the airways and the lungs. Common symptoms include breathlessness, abnormal sputum and a chronic cough. Exacerbations and comorbidities – such as cardiovascular diseases, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, depression and lung cancer – contribute to the overall severity of individual patients (4,5). In 2010, COPD accounted for over 235,000 deaths in the Americas, ranking as the sixth leading cause of mortality regionally. About 23% of these deaths occurred prematurely, in people aged 30-69 years (2). An estimated 13.2 million people live with COPD in the region (1). Many people suffer from this disease for years, experiencing disa- bility and major adverse effects on their quality of life (5,6). In 2012, COPD was responsible for the loss of 8.3 million DALYs, representing the seventh leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost (DALYs) in the Americas, with one DALY representing the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health (3,6). -

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management

THIEME Original Research 125 Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management Shibu George1 Sandeep Suresh2 1 Department of ENT, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, India Address for correspondence ShibuGeorge,MS,DNB,Charivukalayil 2 Department of ENT, Little Flower Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India (House), Ettumanoor, Kottayam 686631, Kerala, India (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:125–130. Abstract Introduction Vocal cord dysfunction is characterized by unintentional paradoxical vocal cord movement resulting in abnormal inappropriate adduction, especially during inspiration; this predominantly manifests as unresponsive asthma or unexplained stridor. It is prudent to be well informed about the condition, since the primary presentation may mask other airway disorders. Objective This descriptive study was intended to analyze presentations of vocal cord dysfunction in a tertiary care referral hospital. The current understanding regarding the pathophysiology and management of the condition were also explored. Methods A total of 27 patients diagnosed with vocal cord dysfunction were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, presentations, associations and examination findings. The mechanism of causation, etiological factors implicated, diagnostic considerations and treatment options were evaluated by analysis of the current literature. Results Therewasastrongfemalepredilection noted among the study population (n ¼ 27), which had a mean age of 31. The most common presentations were stridor Keywords (44%) and refractory asthma (41%). Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease was the most ► Vocal Cord common association in the majority (66%) of the patients, with a strong overlay of Dysfunction anxiety, demonstrable in 48% of the patients. ► paradoxical vocal Conclusion Being aware of the condition is key to avoid misdiagnosis in vocal cord cord motion dysfunction. -

Interstitial Lung Disease—Raising the Index of Suspicion in Primary Care

www.nature.com/npjpcrm All rights reserved 2055-1010/14 PERSPECTIVE OPEN Interstitial lung disease: raising the index of suspicion in primary care Joseph D Zibrak1 and David Price2 Interstitial lung disease (ILD) describes a group of diseases that cause progressive scarring of the lung tissue through inflammation and fibrosis. The most common form of ILD is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which has a poor prognosis. ILD is rare and mainly a disease of the middle-aged and elderly. The symptoms of ILD—chronic dyspnoea and cough—are easily confused with the symptoms of more common diseases, particularly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. ILD is infrequently seen in primary care and a precise diagnosis of these disorders can be challenging for physicians who rarely encounter them. Confirming a diagnosis of ILD requires specialist expertise and review of a high-resolution computed tomography scan (HRCT). Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a key role in facilitating the diagnosis of ILD by referring patients with concerning symptoms to a pulmonologist and, in some cases, by ordering HRCTs. In our article, we highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis of ILD and describe the circumstances in which a PCP’s suspicion for ILD should be raised in a patient presenting with chronic dyspnoea on exertion, once more common causes of dyspnoea have been investigated and excluded. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2014) 24, 14054; doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.54; published online 11 September 2014 INTRODUCTION emphysema, in which the airways of the lungs become narrowed Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is an umbrella term, synonymous or blocked so the patient cannot exhale completely. -

Middle Airway Obstructiondit May Be Happening Under Our Noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1

Thorax Online First, published on July 19, 2012 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 Chest clinic OPINION Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 on 19 July 2012. Downloaded from Middle airway obstructiondit may be happening under our noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1 < Additional materials are ABSTRACT for this conceptual error to be refuted.2 The virus is published online only. To view Background Lower airway obstruction has evolved to now understood to spread from nose to lung, and these files please visit the denote pathologies associated with diseases of the lung, appropriate recognition of the close association journal online (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/ whereas, conditions proximal to the lung embody upper between upper and lower airway pathologies has thoraxjnl-2012-202221/content/ airway obstruction. This approach has disconnected had positive outcomes. An example is novel strat- early/recent). diseases of the larynx and trachea from the lung, and egies that may not be able to prevent colds, but 1Lung and Sleep Medicine, removed the ‘middle airway’ from the interest and that could ameliorate virus asthma exacerbations Monash University and Hospital involvement of respiratory physicians and scientists. through the use of inhaled interferon.3 and Monash Institute of Medical However, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction Accumulating evidence suggests that the middle Research (MIMR), Melbourne, of this anatomical region may be a key component of Australia airway plays a key role in airway obstruction either 2Respiratory Medicine, Imperial overall airway obstruction, either independently or in independently or with coexisting lung disease. -

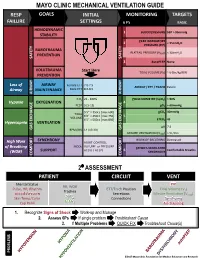

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders

88 XAOIOOIOO Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders Yong Whee Bahk, M.D. and Soo Kyo Chung, M.D. Introduction As a coordinated research project of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a multicentre joint study on radioaerosol lung scan using the BARC nebulizer [1] has prospectively been carried out during 1988-1992 with the participation of 10 member countries in Asia [Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand]. The study was designed so that it would primarily cover chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the other related and common pulmonary diseases. The study also included normal controls and asymptomatic smokers. The purposes of this presentation are three fold: firstly, to document the useful- ness of the nebulizer and the validity of user's protocol in imaging COPD and other lung diseases; secondly, to discuss scan features of the individual COPD and other disorders studied and thirdly, to correlate scan alterations with radiographie find- ings. Before proceeding with a systematic analysis of aerosol scan patterns in the disease groups, we documented normal pattern. The next step was the assessment of scan features in those who had been smoking for more than several years but had no symptoms or signs referable to airways. The lung diseases we analyzed included COPD [emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma and bronchiectasis], bron- chial obstruction, compensatory overinflation and other common lung diseases such as lobar pneumonia, tuberculosis, interstitial fibrosis, diffuse panbronchiolitis, lung edema and primary and metastatic lung cancers. Lung embolism, inhalation burns and glue-sniffer's lung are seperately discussed by Dr. -

Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Exercise-induced Laryngeal Obstruction Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is a breathing problem that affects people during exercise. EILO is defined by inappropriate narrowing of the upper airway at the level of the vocal cords (glottis) and/or supraglottis (above the vocal cords). This can make it hard to get air into your lungs during exercise and cause a noisy breathing that can be frightening. EILO has also been called vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) or paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM). Most people with EILO only have symptoms when they Common signs and symptoms of EILO exercise, those some people may have the problem at During (or immediately after) high-intensity exercise, other times as well. (See ATS Patient Information Series with EILO you may experience: fact sheet ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction/Vocal Cord ■■ Profound shortness of breath or breathlessness Dysfunction’) ■■ Noisy breathing, particularly when breathing in Where are the vocal cords and what do they do? (stridor, gasping, raspy sounds, or “wheezing”) Your vocal cords are located in your upper airway or ■■ A feeling of choking or suffocation that can be scary larynx. Your supraglottic structures (including your ■■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Feeling like there is a lump in the throat arytenoid cartilages and epiglottis) are located above the ■■ Throat or chest tightness vocal cords and are part of your larynx. The larynx is often called the voice box and is deep in your throat. When These symptoms often come on suddenly during you speak, the vocal cords vibrate as you breathe out, exercise, and are typically quite noticeable or concerning to people around you as well. -

Obliterative Bronchiolitis with Atypical Features: CT Scan and Necropsy Findings

Copyright @ERS Journals Ud 1993 Eur Aespir J, 1993, 6, 1221-1225 European Respiratory Journal Printed In UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 CASE REPORT Obliterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: CT scan and necropsy findings M.I.M. Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsfield, I. Gordon, R. Heaton, W.A. Seed, A. Guz Ob/iterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: er scan and necropsy findings. M.l.M. Academic Unit of Cardiovascular Medi Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsjield, l. Gordon, R. Hearon, WA. Seed, A. Guz. ©ERS Journals cine and Depts of Medicine and Pathol l.Jd 1993. ogy, Charing Cross and Westminster ABSTRACT: We describe the natural history of cryptogenic bronchiolitis obliter Medical School. London, and the King ans in a patient foUowed for 24 yrs with serial pulmonary function tests and radi Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst, W . ology. Sussex, UK. Severe, progressive airway obstruction developed, with overinOation but preser Correspondence: M.I.M. Noble, Academic vation of Kco. There was progressive hypoxaemia, which worseroed on exertion; Unit of Cardiovascular Medicine, West hypercapnoca was modest until late in the illness. Neither bronchodilators nor ster minster Hospital, 369 Fulharn Rd, London oids were effective. The chest radiograph remained normal; CT showed irregular SWIO 9NH, UK. areas of low altentuation peripheroUy throughout the lungs, with Bounsfield nu m Keywords: Airway obstruction, bronchi bers typical of emphysema, but no bullae. Postmortem studies included histology olitis obliterans, lung diseases, obstructive and quantitative studies of a corrosion cast of one lung. They showed marked air respiratory insufficiency, pulmonary diffus way narrowing at all levels, with pruning of peripheral branches, mucus plugging, ing capacity.