Interstitial Lung Disease—Raising the Index of Suspicion in Primary Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in COPD (Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema): Morbidity and Mortality

Trends in COPD (Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema): Morbidity and Mortality Please note, this report is designed for double-sided printing American Lung Association Epidemiology and Statistics Unit Research and Health Education Division March 2013 Page intentionally left blank Table of Contents COPD Mortality, 1999-2009 COPD Prevalence, 1999-2011 COPD Hospital Discharges, 1999-2010 Glossary and References List of Tables Table 1: COPD – Number of Deaths by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 1999-2009 Figure 1: COPD – Number of Deaths by Sex, 1999-2009 Figure 2: COPD – Age-Adjusted Death Rates by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 2009 Table 2: COPD – Age-Adjusted Death Rate per 100,000 Population by Ethnic Origin and Sex, 1999- 2009 Figure 3: COPD – Deaths and Age-Adjusted Death Rate by Sex, 2009 Figure 4: COPD – Diagnosed Cases and Evidence of Impaired Lung Function Figure 5: Chronic Bronchitis – Prevalence Rates per 1,000, 2011 Table 3: Chronic Bronchitis – Number of Conditions and Prevalence Rate per 1,000 Population by Ethnic Origin, Sex and Age, 1999-2011 Figure 6: Emphysema – Prevalence Rates per 1,000, 2011 Table 4: Emphysema – Number of Conditions and Prevalence Rate per 1,000 Population by Ethnic Origin, Sex and Age, 1997-2011 Table 5: COPD – Adult Prevalence by Sex and State, 2011 Figure 8: COPD – Age-Adjusted Prevalence in Adults by State, 2011 Table 6: Characteristics Among Those Reporting a Diagnosis of COPD by State (%), 2011 Figure 9: COPD – First-Listed Hospital Discharge Rates per 10,000, 2010 Table 7: COPD – Number of First-Listed Hospital Discharges and Rate per 10,000 Population by Race, Sex and Age, 1999-2010 Figure 9: National Projected Annual Cost of COPD, 2010 Introduction Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a term which refers to a large group of lung diseases characterized by obstruction of air flow that interferes with normal breathing. -

Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease &Bronchiectasis

PLEASE CHECK Editing file BEFORE! Chronic Obstructive lung Disease & Bronchiectasis ★ Objectives: 1. Definition of the two conditions 2. Clinical and radiological diagnosis 3. Differential diagnosis 4. General outline of management 5. Create a link to 341 clinical teaching ★ Resources Used in This lecture: Davidson, Guyton and Becker step 1 lecture notes Done by: Mohammad Alkharraz Contact us at: [email protected] Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD) COPD contains two diseases which are chronic bronchitis and emphysema ■ COPD is classified under obstructive pulmonary diseases along with other (no kidding!) diseases such as asthma and bronchiectasis ■ Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are grouped together under COPD because they are both mainly caused by smoking and they usually present together. ■ Brainless pathology textbooks (Robbins) try to confuse us students with “Pink Puffers” and “Blue Bloaters”. Forget about that as it is not clinically relevant1. Let us quickly point out some points (pathology) that are relevant to each disease (chronic bronchitis and emphysema) and then we will discuss the clinical presentation, management, etc. of COPD Chronic bronchitis It is mainly a clinical diagnosis patients cough up lots of sputum for a long period of time “3 months per year for at least 2 consecutive years2” ● Pathogenesis: Cigarette smoke causes hyperplasia of mucus glands which increase the secretion of mucus → mucus plugs cause obstruction of bronchioles→ COPD Emphysema It is mainly a pathological diagnosis. ● Pathogenesis: 1. Pollutants (smoking)→ increased inflammatory mediators in the lung that destroy the lung parenchyma (trypsin and elastase) 2. We have defense mechanisms to fight these inflammatory mediators (alpha1 antitrypsin) ○ However, the amount of inflammatory mediators exceeds our ability to counteract them 3. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis As a Cause of Bronchial Asthma in Children

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;10(2):95-100. Original article Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis as a cause of bronchial asthma in children Background: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) occurs in Dina Shokry, patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. When aspergillus fumigatus spores Ashgan A. are inhaled they grow in bronchial mucous as hyphae. It occurs in non Alghobashy, immunocompromised patients and belongs to the hypersensitivity disorders Heba H. Gawish*, induced by Aspergillus. Objective: To diagnose cases of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis among asthmatic children and define the Manal M. El-Gerby* association between the clinical and laboratory findings of aspergillus fumigatus (AF) and bronchial asthma. Methods: Eighty asthmatic children were recruited in this study and divided into 50 atopic and 30 non-atopic Departments of children. The following were done: skin prick test for aspergillus fumigatus Pediatrics and and other allergens, measurement of serum total IgE, specific serum Clinical Pathology*, aspergillus fumigatus antibody titer IgG and IgE (AF specific IgG and IgE) Faculty of Medicine, and absolute eosinophilic count. Results: ABPA occurred only in atopic Zagazig University, asthmatics, it was more prevalent with decreased forced expiratory volume Egypt. at the first second (FEV1). Prolonged duration of asthma and steroid dependency were associated with ABPA. AF specific IgE and IgG were higher in the atopic group, they were higher in Aspergillus fumigatus skin Correspondence: prick test positive children than negative ones .Wheal diameter of skin prick Dina Shokry, test had a significant relation to the level of AF IgE titer. Skin prick test Department of positive cases for aspergillus fumigatus was observed in 32% of atopic Pediatrics, Faculty of asthmatic children. -

Coding Billing

CodingCoding&Billing FEBRUARY 2020 Quarterly Editor’s Letter Welcome to the February issue of the ATS Coding and Billing Quarterly. There are several important updates about the final Medicare rules for 2020 that will be important for pulmonary, critical care and sleep providers. Additionally, there is discussion of E/M documentation rules that will be coming in 2021 that practices might need some time to prepare for, and as always, we will answer coding, billing and regulatory compliance questions submitted from ATS members. If you are looking for a more interactive way to learn about the 2020 Medicare final rules, there is a webinar on the ATS website that covers key parts of the Medicare final rules. But before we get to all this important information, I have a request for your help. EDITOR ATS Needs Your Help – Recent Invoices for Bronchoscopes and PFT Lab ALAN L. PLUMMER, MD Spirometers ATS RUC Advisor TheA TS is looking for invoices for recently purchased bronchoscopes and ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS: PFT lab spirometer. These invoices will be used by theA TS to present practice KEVIN KOVITZ, MD expense cost equipment to CMS to help establish appropriate reimbursement Chair, ATS Clinical Practice Committee rates for physician services using this equipment. KATINA NICOLACAKIS, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee • Invoices should not include education or service contract as those ATS Alternate RUC Advisorr are overhead and cannot be considered by CMS for this portion of the STEPHEN P. HOFFMANN, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee formula and payment rates. ATS CPT Advisor • Invoices can be up to five years old. -

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia—Results of Treatment with Clarithromycin Versus Corticosteroids—Observational Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐResults of treatment with clarithromycin versus corticosteroidsÐObservational study Elżbieta Radzikowska1*, Elżbieta Wiatr1☯, Renata Langfort2³, Iwona Bestry3³, Agnieszka Skoczylas4, Ewa Szczepulska-Wo jcik2³, Dariusz Gawryluk1☯, Piotr Rudziński5³, Joanna Chorostowska-Wynimko6³, Kazimierz Roszkowski-Śliż1³ 1 III Department of Lung Disease National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 2 Pathology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 3 Radiology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 4 Geriatrics Department National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 5 Thoracic Surgery Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, a1111111111 Warsaw, Poland, 6 Laboratory of Molecular Diagnostics and Immunology National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland a1111111111 a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Radzikowska E, Wiatr E, Langfort R, Bestry I, Skoczylas A, Szczepulska-WoÂjcik E, et al. (2017) Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐ Background Results of treatment with clarithromycin versus Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a clinicopathological syndrome of unknown ori- corticosteroidsÐObservational study. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184739. -

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (Copd) in the Americas

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) IN THE AMERICAS KEY STATISTICS FOR THE AMERICAS An estimated 13.2 million people live with COPD (1). COPD caused over 235,000 deaths in 2010, ranking as the sixth leading cause of death (2). 7 in 10 COPD deaths are attributable to tobacco (3). In 2012, COPD was responsible for the loss of 8.3 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (3). KEY MESSAGES CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) IS A LEADING CAUSE OF MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY IN THE 1 AMERICAS, REPRESENTING AN IMPORTANT PUBLIC HEALTH CHALLENGE THAT IS BOTH PREVENTABLE AND TREATABLE. COPD is an incurable disease, characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases in the airways and the lungs. Common symptoms include breathlessness, abnormal sputum and a chronic cough. Exacerbations and comorbidities – such as cardiovascular diseases, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, depression and lung cancer – contribute to the overall severity of individual patients (4,5). In 2010, COPD accounted for over 235,000 deaths in the Americas, ranking as the sixth leading cause of mortality regionally. About 23% of these deaths occurred prematurely, in people aged 30-69 years (2). An estimated 13.2 million people live with COPD in the region (1). Many people suffer from this disease for years, experiencing disa- bility and major adverse effects on their quality of life (5,6). In 2012, COPD was responsible for the loss of 8.3 million DALYs, representing the seventh leading cause of disability-adjusted life years lost (DALYs) in the Americas, with one DALY representing the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health (3,6). -

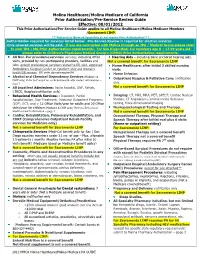

Submitting Requests for Prior Authorization

Molina Healthcare/Molina Medicare of California Prior Authorization/Pre-Service Review Guide Effective: 08/01/2012 This Prior Authorization/Pre-Service Guide applies to all Molina Healthcare/Molina Medicare Members /Sacrament LIHP. ***Referrals to Network Specialists do not require Prior Authorization*** Authorization required for services listed below. Pre-Service Review is required for elective services. Only covered services will be paid. If you are contracted with Molina through an IPA / Medical Group please refer to your IPA / MG Prior Authorization requirements. For San Diego Medi-Cal members age 0 – 17.99 years old please refer to Children’s Physicians Medical Group’s (CPMG) Prior Authorization requirements. All Non-Par providers/services: services, including office Hearing Aids – including bone anchored hearing aids. visits, provided by non-participating providers, facilities and Not a covered benefit for Sacramento LIHP labs, except professional services related to ER visit, approved Home Healthcare: after initial 3 skilled nursing Ambulatory Surgical Center or inpatient stay and Women’s visits health/OB services. ER visits do not require PA Home Infusion Alcohol and Chemical Dependency Services (Medicare & Outpatient Hospice & Palliative Care: notification CHIP only) Refer to Comp Care or Behavioral Health contact information – page 3 only. All Inpatient Admissions: Acute hospital, SNF, Rehab, Not a covered benefit for Sacramento LIHP LTACS, Hospice(notification only) Behavioral Health Services: - Inpatient, Partial Imaging: CT, MRI, MRA, PET, SPECT, Cardiac Nuclear hospitalization, Day Treatment, Intensive Outpatient Programs Studies, CT Angiograms, intimal media thickness (IOP), ECT, and > 12 Office Visits/year for adults and 20 Office testing, three dimensional imaging visits/year for children (Medicare & CHIP only) Refer to Behavioral Neuropsychological Testing and Therapy. -

Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders

88 XAOIOOIOO Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders Yong Whee Bahk, M.D. and Soo Kyo Chung, M.D. Introduction As a coordinated research project of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a multicentre joint study on radioaerosol lung scan using the BARC nebulizer [1] has prospectively been carried out during 1988-1992 with the participation of 10 member countries in Asia [Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand]. The study was designed so that it would primarily cover chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the other related and common pulmonary diseases. The study also included normal controls and asymptomatic smokers. The purposes of this presentation are three fold: firstly, to document the useful- ness of the nebulizer and the validity of user's protocol in imaging COPD and other lung diseases; secondly, to discuss scan features of the individual COPD and other disorders studied and thirdly, to correlate scan alterations with radiographie find- ings. Before proceeding with a systematic analysis of aerosol scan patterns in the disease groups, we documented normal pattern. The next step was the assessment of scan features in those who had been smoking for more than several years but had no symptoms or signs referable to airways. The lung diseases we analyzed included COPD [emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma and bronchiectasis], bron- chial obstruction, compensatory overinflation and other common lung diseases such as lobar pneumonia, tuberculosis, interstitial fibrosis, diffuse panbronchiolitis, lung edema and primary and metastatic lung cancers. Lung embolism, inhalation burns and glue-sniffer's lung are seperately discussed by Dr. -

Weaning from Tracheostomy in Subjects Undergoing Pulmonary

Pasqua et al. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine (2015) 10:35 DOI 10.1186/s40248-015-0032-1 ORIGINALRESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Weaning from tracheostomy in subjects undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation Franco Pasqua1,2*, Ilaria Nardi1, Alessia Provenzano1, Alessia Mari1 on behalf of the Lazio Regional Section, Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists (AIPO) Abstract Background: Weaning from tracheostomy has implications in management, quality of life, and costs of ventilated patients. Furthermore, endotracheal cannula removing needs further studies. Aim of this study was the validation of a protocol for weaning from tracheostomy and evaluation of predictor factors of decannulation. Methods: Medical records of 48 patients were retrospectively evaluated. Patients were decannulated in agreement with a decannulation protocol based on the evaluation of clinical stability, expiratory muscle strength, presence of tracheal stenosis/granulomas, deglutition function, partial pressure of CO2, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio. These variables, together with underlying disease, blood gas analysis parameters, time elapsed with cannula, comordibity, Barthel index, and the condition of ventilation, were evaluated in a logistic model as predictors of decannulation. Results: 63 % of patients were successfully decannulated in agreement with our protocol and no one needed to be re-cannulated. Three variables were significantly associated with the decannulation: no pulmonary underlying diseases (OR = 7.12; 95 % CI 1.2–42.2), no mechanical ventilation (OR = 9.55; 95 % CI 2.1–44.2) and period of tracheostomy ≤10 weeks (OR = 6.5; 95 % CI 1.6–27.5). Conclusions: The positive course of decannulated patients supports the suitability of the weaning protocol we propose here. The strong predictive role of three clinical variables gives premise for new studies testing simpler decannulation protocols. -

Pulmonary Rehabilitation Improves Survival in Patients with Idiopathic

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Pulmonary rehabilitation improves survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis undergoing lung Received: 24 October 2018 Accepted: 21 May 2019 transplantation Published: xx xx xxxx Juliessa Florian1,2,3, Guilherme Watte2,3, Paulo José Zimermann Teixeira3,4, Stephan Altmayer5, Sadi Marcelo Schio2, Letícia Beatriz Sanchez2, Douglas Zaione Nascimento2, Spencer Marcantonio Camargo2, Fabiola Adélia Perin2, José de Jesus Camargo2, José Carlos Felicetti2 & José da Silva Moreira1 This study was conducted to evaluate whether a pulmonary rehabilitation program (PRP) is independently associated with survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis (IPF) undergoing lung transplant (LTx). This quasi-experimental study included 89 patients who underwent LTx due to IPF. Thirty-two completed all 36 sessions in a PRP while on the waiting list for LTx (PRP group), and 53 completed fewer than 36 sessions (controls). Survival after LTx was the main outcome; invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), length of stay (LOS) in intensive care unit (ICU) and in hospital were secondary outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression models were used in survival analyses. Cox regression models showed that the PRP group had a reduced 54.0% (hazard ratio = 0.464, 95% confdence interval 0.222–0.970, p = 0.041) risk of death. A lower number of patients in the PRP group required IMV for more than 24 hours after LTx (9.0% vs. 41.6% p = 0.001). This group also spent a mean of 5 days less in the ICU (p = 0.004) and 5 days less in hospital (p = 0.046). In conclusion, PRP PRP completion halved the risk of cumulative mortality in patients with IPF undergoing unilateral LTx Idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis (IPF) is a non-reversible fbrotic lung disease characterized by a progressive decline of lung function, with a largely unpredictable clinical course and a median survival time of 2–3 years from diag- nosis1,2. -

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Clinical Guideline Diagnosis and Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Timothy J. Wilt, MD, MPH; Steven E. Weinberger, MD; Nicola A. Hanania, MD, MS; Gerard Criner, MD; Thys van der Molen, PhD; Darcy D. Marciniuk, MD; Tom Denberg, MD, PhD; Holger Schu¨ nemann, MD, PhD, MSc; Wisia Wedzicha, PhD; Roderick MacDonald, MS; and Paul Shekelle, MD, PhD, for the American College of Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society* Description: This guideline is an official statement of the American mend treatment with inhaled bronchodilators (Grade: strong recom- College of Physicians (ACP), American College of Chest Physicians mendation, moderate-quality evidence). (ACCP), American Thoracic Society (ATS), and European Respiratory Society (ERS). It represents an update of the 2007 ACP clinical practice Recommendation 4: ACP, ACCP, ATS, and ERS recommend that guideline on diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive clinicians prescribe monotherapy using either long-acting inhaled anti-  pulmonary disease (COPD) and is intended for clinicians who manage cholinergics or long-acting inhaled -agonists for symptomatic patients Ͻ patients with COPD. This guideline addresses the value of history and with COPD and FEV1 60% predicted. (Grade: strong recommenda- physical examination for predicting airflow obstruction; the value of tion, moderate-quality evidence). Clinicians should base the choice of spirometry for screening or diagnosis of COPD; and COPD manage- specific monotherapy on patient preference, cost, and adverse effect ment strategies, specifically evaluation of various inhaled therapies (an- profile. -

Rehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Lung Transplantation (Ltx) Review

pulmonary Research and respiratory medicinE ISSN 2377-1658 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/PRRMOJ-SE-2-109 Open Journal Special Edition “Recent Advances in Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Lung Rehabilitation” Transplantation (LTx) Review Yosuke Izoe, MD*; Taku Harada, MD, PhD; Masahiro Kohzuki, MD, PhD *Corresponding author Yosuke Izoe, MD Professor Department of Internal Medicine and Rehabilitation Science, Tohoku University Graduate Department of Internal Medicine and School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Rehabilitation Science Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Tel. 81-22-717-7353 ABSTRACT Fax: 81-22-717-7355 [email protected] E-mail: Lung transplantation (LTx) has become an established therapeutic option for treating patients with end-stage pulmonary disease. Before and after LTx, physical ability might be restricted Special Edition 2 due to certain effects on respiration, circulation, and skeletal muscles. Severe and chronic lung Article Ref. #: 1000PRRMOJSE2109 disease is associated with physiological changes. Limb muscle dysfunction, inactivity decon- ditioning and nutritional depletion can affect exercise capacity and physical functioning in can- Article History didates for LTx. At present, evidence-based guidelines for exercise training completed in the Received: June 29th, 2017 before and after LTx phases have not been described. However, the use of exercise training for Accepted: July 12th, 2017 chronic respiratory failure conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Published: July 14th, 2017 interstitial lung disease, and cystic fibrosis has been well-documented. This knowledge could be applied to exercise training problems before and after LTx. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has been proven to be effective for the overall improvement of quality of life (QOL) of patients Citation following LTx.