Pulmonary Rehabilitation Improves Survival in Patients with Idiopathic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coding Billing

CodingCoding&Billing FEBRUARY 2020 Quarterly Editor’s Letter Welcome to the February issue of the ATS Coding and Billing Quarterly. There are several important updates about the final Medicare rules for 2020 that will be important for pulmonary, critical care and sleep providers. Additionally, there is discussion of E/M documentation rules that will be coming in 2021 that practices might need some time to prepare for, and as always, we will answer coding, billing and regulatory compliance questions submitted from ATS members. If you are looking for a more interactive way to learn about the 2020 Medicare final rules, there is a webinar on the ATS website that covers key parts of the Medicare final rules. But before we get to all this important information, I have a request for your help. EDITOR ATS Needs Your Help – Recent Invoices for Bronchoscopes and PFT Lab ALAN L. PLUMMER, MD Spirometers ATS RUC Advisor TheA TS is looking for invoices for recently purchased bronchoscopes and ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS: PFT lab spirometer. These invoices will be used by theA TS to present practice KEVIN KOVITZ, MD expense cost equipment to CMS to help establish appropriate reimbursement Chair, ATS Clinical Practice Committee rates for physician services using this equipment. KATINA NICOLACAKIS, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee • Invoices should not include education or service contract as those ATS Alternate RUC Advisorr are overhead and cannot be considered by CMS for this portion of the STEPHEN P. HOFFMANN, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee formula and payment rates. ATS CPT Advisor • Invoices can be up to five years old. -

Interstitial Lung Disease—Raising the Index of Suspicion in Primary Care

www.nature.com/npjpcrm All rights reserved 2055-1010/14 PERSPECTIVE OPEN Interstitial lung disease: raising the index of suspicion in primary care Joseph D Zibrak1 and David Price2 Interstitial lung disease (ILD) describes a group of diseases that cause progressive scarring of the lung tissue through inflammation and fibrosis. The most common form of ILD is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which has a poor prognosis. ILD is rare and mainly a disease of the middle-aged and elderly. The symptoms of ILD—chronic dyspnoea and cough—are easily confused with the symptoms of more common diseases, particularly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. ILD is infrequently seen in primary care and a precise diagnosis of these disorders can be challenging for physicians who rarely encounter them. Confirming a diagnosis of ILD requires specialist expertise and review of a high-resolution computed tomography scan (HRCT). Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a key role in facilitating the diagnosis of ILD by referring patients with concerning symptoms to a pulmonologist and, in some cases, by ordering HRCTs. In our article, we highlight the importance of prompt diagnosis of ILD and describe the circumstances in which a PCP’s suspicion for ILD should be raised in a patient presenting with chronic dyspnoea on exertion, once more common causes of dyspnoea have been investigated and excluded. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2014) 24, 14054; doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.54; published online 11 September 2014 INTRODUCTION emphysema, in which the airways of the lungs become narrowed Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is an umbrella term, synonymous or blocked so the patient cannot exhale completely. -

Submitting Requests for Prior Authorization

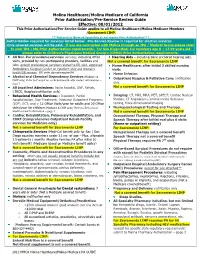

Molina Healthcare/Molina Medicare of California Prior Authorization/Pre-Service Review Guide Effective: 08/01/2012 This Prior Authorization/Pre-Service Guide applies to all Molina Healthcare/Molina Medicare Members /Sacrament LIHP. ***Referrals to Network Specialists do not require Prior Authorization*** Authorization required for services listed below. Pre-Service Review is required for elective services. Only covered services will be paid. If you are contracted with Molina through an IPA / Medical Group please refer to your IPA / MG Prior Authorization requirements. For San Diego Medi-Cal members age 0 – 17.99 years old please refer to Children’s Physicians Medical Group’s (CPMG) Prior Authorization requirements. All Non-Par providers/services: services, including office Hearing Aids – including bone anchored hearing aids. visits, provided by non-participating providers, facilities and Not a covered benefit for Sacramento LIHP labs, except professional services related to ER visit, approved Home Healthcare: after initial 3 skilled nursing Ambulatory Surgical Center or inpatient stay and Women’s visits health/OB services. ER visits do not require PA Home Infusion Alcohol and Chemical Dependency Services (Medicare & Outpatient Hospice & Palliative Care: notification CHIP only) Refer to Comp Care or Behavioral Health contact information – page 3 only. All Inpatient Admissions: Acute hospital, SNF, Rehab, Not a covered benefit for Sacramento LIHP LTACS, Hospice(notification only) Behavioral Health Services: - Inpatient, Partial Imaging: CT, MRI, MRA, PET, SPECT, Cardiac Nuclear hospitalization, Day Treatment, Intensive Outpatient Programs Studies, CT Angiograms, intimal media thickness (IOP), ECT, and > 12 Office Visits/year for adults and 20 Office testing, three dimensional imaging visits/year for children (Medicare & CHIP only) Refer to Behavioral Neuropsychological Testing and Therapy. -

Weaning from Tracheostomy in Subjects Undergoing Pulmonary

Pasqua et al. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine (2015) 10:35 DOI 10.1186/s40248-015-0032-1 ORIGINALRESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Weaning from tracheostomy in subjects undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation Franco Pasqua1,2*, Ilaria Nardi1, Alessia Provenzano1, Alessia Mari1 on behalf of the Lazio Regional Section, Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists (AIPO) Abstract Background: Weaning from tracheostomy has implications in management, quality of life, and costs of ventilated patients. Furthermore, endotracheal cannula removing needs further studies. Aim of this study was the validation of a protocol for weaning from tracheostomy and evaluation of predictor factors of decannulation. Methods: Medical records of 48 patients were retrospectively evaluated. Patients were decannulated in agreement with a decannulation protocol based on the evaluation of clinical stability, expiratory muscle strength, presence of tracheal stenosis/granulomas, deglutition function, partial pressure of CO2, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio. These variables, together with underlying disease, blood gas analysis parameters, time elapsed with cannula, comordibity, Barthel index, and the condition of ventilation, were evaluated in a logistic model as predictors of decannulation. Results: 63 % of patients were successfully decannulated in agreement with our protocol and no one needed to be re-cannulated. Three variables were significantly associated with the decannulation: no pulmonary underlying diseases (OR = 7.12; 95 % CI 1.2–42.2), no mechanical ventilation (OR = 9.55; 95 % CI 2.1–44.2) and period of tracheostomy ≤10 weeks (OR = 6.5; 95 % CI 1.6–27.5). Conclusions: The positive course of decannulated patients supports the suitability of the weaning protocol we propose here. The strong predictive role of three clinical variables gives premise for new studies testing simpler decannulation protocols. -

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Clinical Guideline Diagnosis and Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Timothy J. Wilt, MD, MPH; Steven E. Weinberger, MD; Nicola A. Hanania, MD, MS; Gerard Criner, MD; Thys van der Molen, PhD; Darcy D. Marciniuk, MD; Tom Denberg, MD, PhD; Holger Schu¨ nemann, MD, PhD, MSc; Wisia Wedzicha, PhD; Roderick MacDonald, MS; and Paul Shekelle, MD, PhD, for the American College of Physicians, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society* Description: This guideline is an official statement of the American mend treatment with inhaled bronchodilators (Grade: strong recom- College of Physicians (ACP), American College of Chest Physicians mendation, moderate-quality evidence). (ACCP), American Thoracic Society (ATS), and European Respiratory Society (ERS). It represents an update of the 2007 ACP clinical practice Recommendation 4: ACP, ACCP, ATS, and ERS recommend that guideline on diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive clinicians prescribe monotherapy using either long-acting inhaled anti-  pulmonary disease (COPD) and is intended for clinicians who manage cholinergics or long-acting inhaled -agonists for symptomatic patients Ͻ patients with COPD. This guideline addresses the value of history and with COPD and FEV1 60% predicted. (Grade: strong recommenda- physical examination for predicting airflow obstruction; the value of tion, moderate-quality evidence). Clinicians should base the choice of spirometry for screening or diagnosis of COPD; and COPD manage- specific monotherapy on patient preference, cost, and adverse effect ment strategies, specifically evaluation of various inhaled therapies (an- profile. -

Rehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Lung Transplantation (Ltx) Review

pulmonary Research and respiratory medicinE ISSN 2377-1658 http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/PRRMOJ-SE-2-109 Open Journal Special Edition “Recent Advances in Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Patients Undergoing Lung Rehabilitation” Transplantation (LTx) Review Yosuke Izoe, MD*; Taku Harada, MD, PhD; Masahiro Kohzuki, MD, PhD *Corresponding author Yosuke Izoe, MD Professor Department of Internal Medicine and Rehabilitation Science, Tohoku University Graduate Department of Internal Medicine and School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Rehabilitation Science Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Tel. 81-22-717-7353 ABSTRACT Fax: 81-22-717-7355 [email protected] E-mail: Lung transplantation (LTx) has become an established therapeutic option for treating patients with end-stage pulmonary disease. Before and after LTx, physical ability might be restricted Special Edition 2 due to certain effects on respiration, circulation, and skeletal muscles. Severe and chronic lung Article Ref. #: 1000PRRMOJSE2109 disease is associated with physiological changes. Limb muscle dysfunction, inactivity decon- ditioning and nutritional depletion can affect exercise capacity and physical functioning in can- Article History didates for LTx. At present, evidence-based guidelines for exercise training completed in the Received: June 29th, 2017 before and after LTx phases have not been described. However, the use of exercise training for Accepted: July 12th, 2017 chronic respiratory failure conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Published: July 14th, 2017 interstitial lung disease, and cystic fibrosis has been well-documented. This knowledge could be applied to exercise training problems before and after LTx. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has been proven to be effective for the overall improvement of quality of life (QOL) of patients Citation following LTx. -

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary Rehabilitation Date of Origin: 06/2005 Last Review Date: 10/28/2020 Effective Date: 11/02/2020 Dates Reviewed: 05/2006, 05/2007, 05/2008, 11/2009, 02/2011, 01/2012, 08/2013, 07/2014, 09/2015, 11/2016, 10/2017, 10/2018, 10/2019, 10/2020 Developed By: Medical Necessity Criteria Committee I. Description Pulmonary rehabilitation is a restorative and preventative process for patients who are diagnosed with a chronic pulmonary disease. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs utilize a multidisciplinary approach in the areas of exercise training, psychosocial support, education, and follow-up. The purpose of the program is to help individuals improve their quality of life and restore them to their highest possible functional capacity. II. Criteria: CWQI HCS-0057 A. Medically supervised outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation will be covered to plan limitations for 1 or more of the following conditions a. The patient has a diagnosis of chronic pulmonary disease and ALL of the following: i. The patient is referred by a board-certified pulmonologist or primary care physician who is actively involved in the patient‘s care. ii. The patient has been diagnosed with 1 or more of the following: 1. Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency 2. Asbestosis 3. Asthma 4. Chronic airflow obstruction 5. Chronic bronchitis 6. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 7. Cystic fibrosis 8. Fibrosing alveolitis 9. Pneumoconiosis 10. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis 11. Pulmonary fibrosis 12. Pulmonary hemosiderosis 13. Radiation pneumonitis 14. Other documented chronic lung disease or conditions that affect pulmonary function, such as (not all-inclusive): a. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) b. Ankylosing spondylitis c. -

A PATIENT GUIDE to Valve Therapy for Treatment of Severe Emphysema

A PATIENT GUIDE To Valve Therapy for Treatment of Severe Emphysema Caution: Federal (USA) Law restricts this device to sale by or on the order of a physician TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE COPD and Emphysema . 3 Treatment Choices . 5 Device Description . .6 Intended Use . .8 Potential Risks and Benefits . .9 The Procedure . .12 Patient Information Card . .16 My Care Regimen . 17 Valve Removal . 18 Frequently Asked Questions . .19 Glossary . 21 My Lungs . .24 My Notes . .25 My Procedure . .26 2 CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) AND EMPHYSEMA If you are reading this booklet then it’s most likely that you or a loved one has been diagnosed with COPD . COPD is an umbrella term used to describe progressive lung diseases including emphysema, chronic bronchitis, refractory (non-reversible) asthma, and some forms of bronchiectasis . Every affected person’s experience is different . The characteristic symptoms of COPD include frequent coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, feeling tired — especially when doing daily activities and exercise — a tight feeling in the chest, and increased mucus in the lungs . As the chronic disease progresses, your symptoms will tend to get worse as more damage occurs in the lungs . bronchi air sacs Figure 1. 3 Emphysema A consequence of chronic inflammation of lung tissue is pulmonary emphysema . Emphysema is one of the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases . With every breath, lungs deliver oxygen to the rest of the body to perform essential life functions . Lungs are made up of tiny air sacs which absorb the oxygen in the air you breathe (Figure 2) called alveoli . In patients with emphysema, these air sacs are gradually destroyed and lose their elastic strength, which makes it difficult for air to exit the air sacs . -

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Pulmonary Rehabilitation If you have shortness of breath because of lung problems, you may have asked yourself: • Can I exercise? • How can I get in better shape? • What medications should I be taking? • Can I do anything to improve my overall well-being? Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) can help answer these How will I know if Pulmonary Rehabilitation is and other questions. Participating in a PR program will right for me? help decrease your shortness of breath and increase your Your healthcare provider will determine if you qualify for ability to exercise. You may have heard that pulmonary pulmonary rehabilitation by: rehabilitation is only for people with COPD (chronic ■■ Evaluating your current state of health and lung obstructive pulmonary disease). We now know that people with other lung conditions such as pulmonary function test results hypertension, interstitial lung disease, pre/post transplant, ■■ Discussing your current activity level and your ability to and cystic fibrosis can benefit as well. do the things you want to do ■■ Determining your willingness and ability to attend. What is Pulmonary Rehabilitation? Pulmonary rehabilitation programs are limited in the Pulmonary rehabilitation is a program of education and number of people who can attend so that you get close exercise that helps you manage your breathing problem, supervision. You will be evaluated before you begin the CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP increase your stamina (energy) and decrease your program to make sure you do not have health issues that breathlessness. The education part of the program teaches you to be “in charge” of your breathing instead of your would limit your ability to join. -

Exercise Training for Lung Transplant Candidates and Recipients: a Systematic Review

REVIEW EXERCISE TRAINING Exercise training for lung transplant candidates and recipients: a systematic review Emily Hume1, Lesley Ward1, Mick Wilkinson1, James Manifield 1, Stephen Clark1,2 and Ioannis Vogiatzis1 Affiliations: 1Dept of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Life Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK. 2Cardiothoracic Centre, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Correspondence: Ioannis Vogiatzis, Dept of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Northumbria University, Northumberland Building, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8ST, UK. E-mail: [email protected] @ERSpublications Both inpatient and outpatient exercise training appears beneficial for improving exercise capacity and quality of life in lung transplant candidates and recipients. Further research investigating the effect on post-surgery clinical outcomes is required. https://bit.ly/2XD6J6S Cite this article as: Hume E, Ward L, Wilkinson M, et al. Exercise training for lung transplant candidates and recipients: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev 2020; 29: 200053 [https://doi.org/10.1183/ 16000617.0053-2020]. ABSTRACT Exercise intolerance and impaired quality of life (QoL) are characteristic of lung transplant candidates and recipients. This review investigated the effects of exercise training on exercise capacity, QoL and clinical outcomes in pre- and post-operative lung transplant patients. A systematic literature search of PubMed, Nursing and Allied Health, Cochrane (CENTRAL), Scopus and CINAHL databases was conducted from inception until February, 2020. The inclusion criteria were assessment of the impact of exercise training before or after lung transplantation on exercise capacity, QoL or clinical outcomes. 21 studies met the inclusion criteria, comprising 1488 lung transplant candidates and 1108 recipients. -

Respiratory Therapy, Pulmonary Rehabilitation and Pulmonary Services – Medicare Advantage Coverage Summary

UnitedHealthcare® Medicare Advantage Coverage Summary Respiratory Therapy, Pulmonary Rehabilitation and Pulmonary Services Policy Number: MCS081.03 Approval Date: August 17, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Related Policies Coverage Guidelines ..................................................................... 1 None Pulmonary Rehabilitation ........................................................... 1 Postural Drainage and Pulmonary Exercises ............................ 2 High Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation (HFCWO) Devices ...... 2 Nebulized Beta Adrenergic Agonist Therapy ........................... 2 Heat Treatment, Including the Use of Diathermy and Ultrasound for Pulmonary Conditions ....................................... 2 Bronchial Thermoplasty ............................................................. 3 Lung Volume Reduction Surgery (LVRS) .................................. 3 Definitions ...................................................................................... 3 Policy History/Revision Information ............................................. 3 Instructions for Use ....................................................................... 3 Coverage Guidelines Pulmonary rehabilitation services are covered when Medicare coverage criteria are met. DME Face to Face Requirement: Effective July 1, 2013, Section 6407 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established a face-to- face encounter requirement for certain items of DME (including stationary compressed gas oxygen system; cough stimulating device; -

Bronchoscopic Lung Volume Reduction Operation and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

https://www.scientificarchives.com/journal/journal-of-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Review Article Bronchoscopic Lung Volume Reduction Operation and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Esra Pehlivan* University of Health Sciences Turkey, Faculty of Hamidiye Health Sciences, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, İstanbul, Turkey *Correspondence should be addressed to Esra Pehlivan; [email protected] Received date: February 03, 2021, Accepted date: June 16, 2021 Copyright: © 2021 Pehlivan E. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Dyspnea and reduced exercise capacity negatively affect the quality of life in many Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients with emphysema phenotype. Surgical procedures may be preferred in cases where improvement in respiratory functions cannot be achieved despite pharmacological treatments. These surgical operations are bullectomy, lung transplantation, lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) or bronchoscopic lung volume reduction (BLVR). Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a well-established and widely accepted standard therapy in order to alleviate symptoms and optimize pulmonary functions. It is stated in the guidelines and reports that receiving of PR before the bronchoscopic interventions is a necessity. Moreover, there are very few studies on this subject. In this review, PR will be discussed in relation to BLVR. Keywords: Coil, Dyspnea, Exercise, Physiotherapy, Valve Emphysema and Hyperinflation trapping, or dynamic hyperinflation, which becomes much more exaggerated with exercise. The lungs, which become The main symptom in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary excessively swollen with dynamic hyperinflation, cannot Disease (COPD) is shortness of breath.