Risk Factors for Diagnostic Delay in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Nils Hoyer1* , Thomas Skovhus Prior2, Elisabeth Bendstrup2, Torgny Wilcke1 and Saher Burhan Shaker1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management

THIEME Original Research 125 Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management Shibu George1 Sandeep Suresh2 1 Department of ENT, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, India Address for correspondence ShibuGeorge,MS,DNB,Charivukalayil 2 Department of ENT, Little Flower Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India (House), Ettumanoor, Kottayam 686631, Kerala, India (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:125–130. Abstract Introduction Vocal cord dysfunction is characterized by unintentional paradoxical vocal cord movement resulting in abnormal inappropriate adduction, especially during inspiration; this predominantly manifests as unresponsive asthma or unexplained stridor. It is prudent to be well informed about the condition, since the primary presentation may mask other airway disorders. Objective This descriptive study was intended to analyze presentations of vocal cord dysfunction in a tertiary care referral hospital. The current understanding regarding the pathophysiology and management of the condition were also explored. Methods A total of 27 patients diagnosed with vocal cord dysfunction were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, presentations, associations and examination findings. The mechanism of causation, etiological factors implicated, diagnostic considerations and treatment options were evaluated by analysis of the current literature. Results Therewasastrongfemalepredilection noted among the study population (n ¼ 27), which had a mean age of 31. The most common presentations were stridor Keywords (44%) and refractory asthma (41%). Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease was the most ► Vocal Cord common association in the majority (66%) of the patients, with a strong overlay of Dysfunction anxiety, demonstrable in 48% of the patients. ► paradoxical vocal Conclusion Being aware of the condition is key to avoid misdiagnosis in vocal cord cord motion dysfunction. -

Diagnostic Delay and Associated Factors Among Patients With

Said et al. Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2017) 6:64 DOI 10.1186/s40249-017-0276-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Diagnostic delay and associated factors among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Khadija Said1,2,3*, Jerry Hella1,2,3, Grace Mhalu1,2,3, Mary Chiryankubi4, Edward Masika4, Thomas Maroa1, Francis Mhimbira1,2,3, Neema Kapalata4 and Lukas Fenner1,2,3,5* Abstract Background: Tanzania is among the 30 countries with the highest tuberculosis (TB) burdens. Because TB has a long infectious period, early diagnosis is not only important for reducing transmission, but also for improving treatment outcomes. We assessed diagnostic delay and associated factors among infectious TB patients. Methods: We interviewed new smear-positive adult pulmonary TB patients enrolled in an ongoing TB cohort study in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, between November 2013 and June 2015. TB patients were interviewed to collect information on socio-demographics, socio-economic status, health-seeking behaviour, and residential geocodes. We categorized diagnostic delay into ≤ 3 or > 3 weeks. We used logistic regression models to identify risk factors for diagnostic delay, presented as crude (OR) and adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR). We also assessed association between geographical distance (incremental increase of 500 meters between household and the nearest pharmacy) with binary outcomes. Results: We analysed 513 patients with a median age of 34 years (interquartile range 27–41); 353 (69%) were men. Overall, 444 (87%) reported seeking care from health care providers prior to TB diagnosis, of whom 211 (48%) sought care > 2 times. Only six (1%) visited traditional healers before TB diagnosis. -

Patient and Health System Delay Among TB Patients in Ethiopia: Nationwide Mixed Method Cross-Sectional Study Daniel G

Datiko et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:1126 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08967-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Patient and health system delay among TB patients in Ethiopia: Nationwide mixed method cross-sectional study Daniel G. Datiko1* , Degu Jerene1 and Pedro Suarez2 Abstract Background: Effective tuberculosis (TB) control is the end result of improved health seeking by the community and timely provision of quality TB services by the health system. Rapid expansion of health services to the peripheries has improved access to the community. However, high cost of seeking care, stigma related TB, low index of suspicion by health care workers and lack of patient centered care in health facilities contribute to delays in access to timely care that result in delay in seeking care and hence increase TB transmission, morbidity and mortality. We aimed to measure patient and health system delay among TB patients in Ethiopia. Methods: This is mixed method cross-sectional study conducted in seven regions and two city administrations. We used multistage cluster sampling to randomly select 40 health centers and interviewed 21 TB patients per health center. We also conducted qualitative interviews to understand the reasons for delay. Results: Of the total 844 TB patients enrolled, 57.8% were men. The mean (SD) age was 34 (SD + 13.8) years. 46.9% of the TB patients were the heads of household, 51.4% were married, 24.1% were farmers and 34.7% were illiterate. The median (IQR) patient, diagnostic and treatment initiation delays were 21 (10–45), 4 (2–10) and 2 (1–3) days respectively. -

Middle Airway Obstructiondit May Be Happening Under Our Noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1

Thorax Online First, published on July 19, 2012 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 Chest clinic OPINION Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 on 19 July 2012. Downloaded from Middle airway obstructiondit may be happening under our noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1 < Additional materials are ABSTRACT for this conceptual error to be refuted.2 The virus is published online only. To view Background Lower airway obstruction has evolved to now understood to spread from nose to lung, and these files please visit the denote pathologies associated with diseases of the lung, appropriate recognition of the close association journal online (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/ whereas, conditions proximal to the lung embody upper between upper and lower airway pathologies has thoraxjnl-2012-202221/content/ airway obstruction. This approach has disconnected had positive outcomes. An example is novel strat- early/recent). diseases of the larynx and trachea from the lung, and egies that may not be able to prevent colds, but 1Lung and Sleep Medicine, removed the ‘middle airway’ from the interest and that could ameliorate virus asthma exacerbations Monash University and Hospital involvement of respiratory physicians and scientists. through the use of inhaled interferon.3 and Monash Institute of Medical However, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction Accumulating evidence suggests that the middle Research (MIMR), Melbourne, of this anatomical region may be a key component of Australia airway plays a key role in airway obstruction either 2Respiratory Medicine, Imperial overall airway obstruction, either independently or in independently or with coexisting lung disease. -

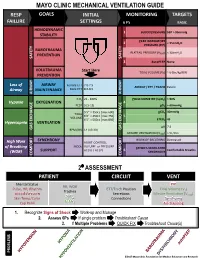

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Exercise-induced Laryngeal Obstruction Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is a breathing problem that affects people during exercise. EILO is defined by inappropriate narrowing of the upper airway at the level of the vocal cords (glottis) and/or supraglottis (above the vocal cords). This can make it hard to get air into your lungs during exercise and cause a noisy breathing that can be frightening. EILO has also been called vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) or paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM). Most people with EILO only have symptoms when they Common signs and symptoms of EILO exercise, those some people may have the problem at During (or immediately after) high-intensity exercise, other times as well. (See ATS Patient Information Series with EILO you may experience: fact sheet ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction/Vocal Cord ■■ Profound shortness of breath or breathlessness Dysfunction’) ■■ Noisy breathing, particularly when breathing in Where are the vocal cords and what do they do? (stridor, gasping, raspy sounds, or “wheezing”) Your vocal cords are located in your upper airway or ■■ A feeling of choking or suffocation that can be scary larynx. Your supraglottic structures (including your ■■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Feeling like there is a lump in the throat arytenoid cartilages and epiglottis) are located above the ■■ Throat or chest tightness vocal cords and are part of your larynx. The larynx is often called the voice box and is deep in your throat. When These symptoms often come on suddenly during you speak, the vocal cords vibrate as you breathe out, exercise, and are typically quite noticeable or concerning to people around you as well. -

Diagnostic Delay of Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 30 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.637375 Diagnostic Delay of Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients Federica Melazzini 1*, Margherita Reduzzi 1, Silvana Quaglini 2, Federica Fumoso 1, Marco Vincenzo Lenti 1 and Antonio Di Sabatino 1* 1 Department of Internal Medicine, San Matteo Hospital Foundation, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, 2 Department of Electrical, Computer, and Biomedical Engineering, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a frequent, life-threatening COVID-19 complication, whose diagnosis can be challenging because of its non-specific symptoms. There are no studies assessing the impact of diagnostic delay on COVID-19 related PE. The aim of our exploratory study was to assess the diagnostic delay of PE in COVID-19 patients, and to identify potential associations between patient- or physician-related variables and the delay. This is a single-center observational retrospective study that included 29 consecutive COVID-19 patients admitted to the San Matteo Hospital Foundation between February and May 2020, with a diagnosis of PE, and a control population of Edited by: Zisis Kozlakidis, 23 non-COVID-19 patients admitted at our hospital during the same time lapse in 2019. International Agency for Research on We calculated the patient-related delay (i.e., the time between the onset of the symptoms Cancer (IARC), France and the first medical examination), and the physician-related delay (i.e., the time between Reviewed by: the first medical examination and the diagnosis of PE). The overall diagnostic delay Pedro Xavier-Elsas, Federal University of Rio de significantly correlated with the physician-related delay (p < 0.0001), with the tendency Janeiro, Brazil to a worse outcome in long physician-related diagnostic delay (p = 0.04). -

Obliterative Bronchiolitis with Atypical Features: CT Scan and Necropsy Findings

Copyright @ERS Journals Ud 1993 Eur Aespir J, 1993, 6, 1221-1225 European Respiratory Journal Printed In UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 CASE REPORT Obliterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: CT scan and necropsy findings M.I.M. Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsfield, I. Gordon, R. Heaton, W.A. Seed, A. Guz Ob/iterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: er scan and necropsy findings. M.l.M. Academic Unit of Cardiovascular Medi Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsjield, l. Gordon, R. Hearon, WA. Seed, A. Guz. ©ERS Journals cine and Depts of Medicine and Pathol l.Jd 1993. ogy, Charing Cross and Westminster ABSTRACT: We describe the natural history of cryptogenic bronchiolitis obliter Medical School. London, and the King ans in a patient foUowed for 24 yrs with serial pulmonary function tests and radi Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst, W . ology. Sussex, UK. Severe, progressive airway obstruction developed, with overinOation but preser Correspondence: M.I.M. Noble, Academic vation of Kco. There was progressive hypoxaemia, which worseroed on exertion; Unit of Cardiovascular Medicine, West hypercapnoca was modest until late in the illness. Neither bronchodilators nor ster minster Hospital, 369 Fulharn Rd, London oids were effective. The chest radiograph remained normal; CT showed irregular SWIO 9NH, UK. areas of low altentuation peripheroUy throughout the lungs, with Bounsfield nu m Keywords: Airway obstruction, bronchi bers typical of emphysema, but no bullae. Postmortem studies included histology olitis obliterans, lung diseases, obstructive and quantitative studies of a corrosion cast of one lung. They showed marked air respiratory insufficiency, pulmonary diffus way narrowing at all levels, with pruning of peripheral branches, mucus plugging, ing capacity. -

Diagnostic Test Interpretation and Referral Delay in Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Diagnostic test interpretation and referral delay in patients with interstitial lung disease. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/282365v7 Journal Respiratory research, 20(1) ISSN 1465-9921 Authors Pritchard, David Adegunsoye, Ayodeji Lafond, Elyse et al. Publication Date 2019-11-12 DOI 10.1186/s12931-019-1228-2 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Pritchard et al. Respiratory Research (2019) 20:253 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1228-2 RESEARCH Open Access Diagnostic test interpretation and referral delay in patients with interstitial lung disease David Pritchard1, Ayodeji Adegunsoye2, Elyse Lafond3, Janelle Vu Pugashetti4, Ryan DiGeronimo5, Noelle Boctor1, Nandini Sarma1, Isabella Pan2, Mary Strek2, Michael Kadoch5, Jonathan H. Chung6 and Justin M. Oldham4,7* Abstract Background: Diagnostic delays are common in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD). A substantial percentage of patients experience a diagnostic delay in the primary care setting, but the factors underpinning this observation remain unclear. In this multi-center investigation, we assessed ILD reporting on diagnostic test interpretation and its association with subsequent pulmonology referral by a primary care physician (PCP). Methods: A retrospective cohort analysis of patients referred to the ILD programs at UC-Davis and University of Chicago by a PCP within each institution was performed. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen and pulmonary function test (PFT) were reviewed to identify the date ILD features were first present and determine the time from diagnostic test to pulmonology referral. The association between ILD reporting on diagnostic test interpretation and pulmonology referral was assessed, as was the association between years of diagnostic delay and changes in fibrotic features on longitudinal chest CT. -

Delayed Diagnosis of Acute Ischemic Stroke in Children - a Registry-Based Study in Switzerland

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2011 Delayed diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in children - a registry-based study in Switzerland Martin, C ; von Elm, E ; El-Koussy, M ; Boltshauser, E ; Steinlin, M Abstract: QUESTIONS UNDER STUDY/PRINCIPLES: After arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) an early diagnosis helps preserve treatment options that are no longer available later. Paediatric AIS is difficult to diagnose and often the time to diagnosis exceeds the time window of 6 hours defined for thrombolysis in adults. We investigated the delay from the onset of symptoms to AIS diagnosis in children and potential contributing factors. METHODS: We included children with AIS below 16 years from the population- based Swiss Neuropaediatric Stroke Registry (2000-2006). We evaluated the time between initial medical evaluation for stroke signs/symptoms and diagnosis, risk factors, co-morbidities and imaging findings. RESULTS: A total of 91 children (61 boys), with a median age of 5.3 years (range: 0.2-16.2), were included. The time to diagnosis (by neuro-imaging) was <6 hours in 32 (35%), 6-12 hours in 23 (25%), 12-24 hours in 15 (16%) and >24 hours in 21 (23%) children. Of 74 children not hospitalised when the stroke occurred, 42% had adequate outpatient management. Delays in diagnosis were attributed to: parents/caregivers (n = 20), physicians of first referral (n = 5) and tertiary care hospitals (n= 8). A co-morbidity hindered timely diagnosis in eight children. No other factors were associated with delay to diagnosis. -

Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Workers Exposed to Food Flavorings

HEALTH ALERT Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Workers Exposed to Food Flavorings Recently, several investigations have identified clusters of workers diagnosed with bronchiolitis obliterans (commonly referred to as “popcorn workers’ lung” and “flavorings-related lung disease”), a form of fixed, irreversible airway obstruction, after exposure to mixtures of butter flavoring chemicals. Evaluations of these workers revealed high rates of both severe respiratory symptoms and significantly compromised lung function.1 These investigations concluded that there is a risk for occupational lung disease in workers with inhalation exposure to butter flavoring chemicals.2 Other investigations have also shown that workers that use or manufacture certain food flavoring additives have developed similar health problems. Diacetyl and Other Food Flavorings Used in Food and Flavoring Manufacturing Food flavorings can be either natural or manmade. Some are comprised of only one ingredient, but others are complex mixtures of several substances. Diacetyl is a chemical used in the manufacture of butter flavoring and other food flavorings and is the suspected cause of several cases of bronchiolitis obliterans in workers. During the manufacturing process, workers may be exposed to food flavorings in the form of vapors, dusts, or sprays. There are many different types of food flavorings and most have not been tested for respiratory toxicity. However, recent animal studies of diacetyl exposure conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) have shown an association between diacetyl and fixed obstructive pulmonary disease. What are the health effects associated with flavorings-related lung disease? Exposure to certain airborne food flavorings is associated with higher rates of respiratory symptoms such as coughing, shortness of breath, fatigue, and difficulty breathing with exertion or exercise. -

Focus on Bronchiectasis/COPD Overlap: an Under-Recognized but Critically Important Condition

Focus on Bronchiectasis/COPD Overlap: An Under-Recognized But Critically Important Condition Gary Hansen, PhD Former “Orphan Disease” Grows in Recognition Recognizing • Chronic productive cough Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB)1 is an important Bronchiectasis2 disease that remains largely unknown. Once thought to be a rare • Chronic mucus hypersecretion “orphan” condition—merely the aftermath of infectious diseases • Chronic antibiotic use that are now readily treated—emerging evidence now shows that NCFB is far more common than originally believed and is closely • Frequent hospitalizations associated with another better known major respiratory health • Reduced quality of life threat—COPD.3 Defined as the thickening and enlargement of the airways resulting from chronic inflammation, bronchiectasis damages normal airway clearance mechanisms and results in the The process is irreversible and there is no known cure— accumulation of excess secretions. As a result, patients face fortunately, appropriate care can substantially improve the chronic cough, excess sputum production, and a recurring cycle lives of affected patients. of hospitalizations.2 Appropriate diagnosis and treatment are key to improving quality of life and reducing the need for expensive While bronchiectasis may be found at any age, it is most often medical care. Specifically, airway clearance therapy directly a disease of middle-age and older. The profile of a patient with addresses the problem of purulent sputum retained in the bronchiectasis is in many ways similar to that of chronic airways and by “emptying the Petri dish” can help to reduce the bronchitis.8 Affected patients often have a chronic productive risk of future exacerbations without risking exposure to the cough for more than three months of the year along with negative effects of long-term orWhile rotating bronchiectasis antibiotics.