Pediatric Laryngospasm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laryngospasm Caused by Removal of Nasogastric Tube After Tracheal Extubation: Case Report

Yanaka A, et al. J Anesth Clin Care 2021, 8: 061 DOI: 10.24966/ACC-8879/100061 HSOA Journal of Anesthesia & Clinical Care Case Report pCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide pO : Partial pressure of oxygen Laryngospasm Caused by 2 mmHg: Millimeter of mercury Removal of Nasogastric Tube mg/dl: Milligram per deciliter mmol/L: Millimole per litter after Tracheal Extubation: Case Introduction Report Background Laryngospasm (spasmodic closure of the larynx) is an airway Ayumi Yanaka1 and Takuo Hoshi2* complication that may occur when a patient emerges from general 1Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Ibaraki Prefectur- anesthesia. It is a protective reflex, but may sometimes result in al Central Hospital, Japan pulmonary aspiration, pulmonary edema, arrhythmia and cardiac 2Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Clinical and Edu- arrest [1]. It does not often cause severe hypoxemia in the patient, and cational Training Center, Tsukuba University Hospital, Japan our review of the literature revealed no previous reports of such cases that cause of the laryngospasm was the removal of nasogastric tube. Here, we describe this significant adverse event in a case and suggest Abstract ways to lessen the possibility of its occurrence. We obtained written informed consent for publication of this case report from the patient. Background: We report a case of laryngospasm during nasogastric tube removal. Laryngospasm is a severe airway complication after Case report surgery and there have been no reports associated with the removal of nasogastric tubes. A 54-year-old woman height, 157 cm; weight, 61 kg underwent abdominal surgery (partial hepatectomy with right partial Case Report: After abdominal surgery, the patient was extubated the tracheal tube, and was removed the nasogastric tube. -

Hanging, Strangulation and Other Forms of Asphyxiation

Hanging, Strangulation and Other Forms of Asphyxiation Steven Campman, M.D. Chief Deputy Medical Examiner San Diego County 16 October 2018 Overview • Terms • Other forms of asphyxiation • Neck Compression –Hanging –Strangulation Asphyxia • The physical and chemical state caused by the interference with normal respiration. • A condition that interferes with cells ability to receive or use oxygen. General Effects • Decrease and cessation of breathing • Leads to bradycardia and eventually asystole • Slowing, then flattening of the EEG Many Terms • Gag: to obstruct the mouth • Choke: to compress or otherwise obstruct the airway • Strangle: asphyxia by external compression of the throat •Throttle: same as strangle; especially manual strangulation • Garrote: strangle; especially ligature strangulation •Burking: chest compression and smothering. Many Terms • Suffocate: (broad term) a layperson’s synonym for asphyxiation, sometimes used to mean smother. • Choke –a layperson’s term for strangulation –A medical term for internal blocking of the airway Classification of Asphyxia Neck Airway Mechanical Exclusion Compression Obstruction Asphyxia of Oxygen Airway Obstruction •Smothering •Gagging •Choking (laryngeal blockage, aspiration, food bolus) Suicide Kit Choking Internal obstruction of airway • Mouth: gag • Larynx or trachea: obstruction by foreign body, “café coronary,” anaphylaxis, laryngospasm, epiglottitis • Tracheobronchial tree: aspiration, drowning FOOD BOLUS Anaphylaxis from Wasp Stings Mechanical Asphyxia Ability to breath is compromised -

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management

THIEME Original Research 125 Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management Shibu George1 Sandeep Suresh2 1 Department of ENT, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, India Address for correspondence ShibuGeorge,MS,DNB,Charivukalayil 2 Department of ENT, Little Flower Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India (House), Ettumanoor, Kottayam 686631, Kerala, India (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:125–130. Abstract Introduction Vocal cord dysfunction is characterized by unintentional paradoxical vocal cord movement resulting in abnormal inappropriate adduction, especially during inspiration; this predominantly manifests as unresponsive asthma or unexplained stridor. It is prudent to be well informed about the condition, since the primary presentation may mask other airway disorders. Objective This descriptive study was intended to analyze presentations of vocal cord dysfunction in a tertiary care referral hospital. The current understanding regarding the pathophysiology and management of the condition were also explored. Methods A total of 27 patients diagnosed with vocal cord dysfunction were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, presentations, associations and examination findings. The mechanism of causation, etiological factors implicated, diagnostic considerations and treatment options were evaluated by analysis of the current literature. Results Therewasastrongfemalepredilection noted among the study population (n ¼ 27), which had a mean age of 31. The most common presentations were stridor Keywords (44%) and refractory asthma (41%). Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease was the most ► Vocal Cord common association in the majority (66%) of the patients, with a strong overlay of Dysfunction anxiety, demonstrable in 48% of the patients. ► paradoxical vocal Conclusion Being aware of the condition is key to avoid misdiagnosis in vocal cord cord motion dysfunction. -

The “Best” Way to Breath

Journal of Lung, Pulmonary & Respiratory Research Case Report Open Access The “Best” way to breath Abstract Volume 2 Issue 2 - 2015 A “best” way to breath is described resulting from discovering a pre-Heimlich method Samuel A Nigro of preventing choking. Because of four episodes in three months of terrifying complete laryngospasm, the physician-patient-writer, consistent with many medical discoveries Retired, Assistant Clinical Professor Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, USA in history, discovered a method of aborting the episodes. Breathing has always been taken for granted as spontaneously and naturally most efficient. To the contrary, Correspondence: Samuel A Nigro, Retired, Assistant Clinical nasal breathing is best with first closing the mouth which enhances oxygenation and Professor Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School trans-laryngeal respiration. Physiologic aspects are reviewed including nasal and oral of Medicine, 2517 Guilford Road, Cleveland Heights, Ohio respiratory distinctions, laryngeal musculature and structures, diaphragm control and 44118, USA, Tel (216) 932-0575, Email [email protected] neuro-functional speculations. Proposed is the SAM: Shut your mouth, Air in nose, and then Mouth cough (or exhale). Benefits include prevention of choking making the Received: January 07, 2015 | Published: January 26, 2015 Heimlich unnecessary; more efficient clearing of the throat and coughs; improving oxygenation at molecular level of likely benefit for pre-cardiac or pre-stroke anoxic crises; improving exertion endurance; and offering a psycho physiologic method for emotional crises as panics, rages, and obsessive-compulsive impulses. This is a simple universal public health technique needing universal promulgation for the integration of care for all work forces and everyone else. -

Dive Medicine Aide-Memoire Lt(N) K Brett Reviewed by Lcol a Grodecki Diving Physics Physics

Dive Medicine Aide-Memoire Lt(N) K Brett Reviewed by LCol A Grodecki Diving Physics Physics • Air ~78% N2, ~21% O2, ~0.03% CO2 Atmospheric pressure Atmospheric Pressure Absolute Pressure Hydrostatic/ gauge Pressure Hydrostatic/ Gauge Pressure Conversions • Hydrostatic/ gauge pressure (P) = • 1 bar = 101 KPa = 0.987 atm = ~1 atm for every 10 msw/33fsw ~14.5 psi • Modification needed if diving at • 10 msw = 1 bar = 0.987 atm altitude • 33.07 fsw = 1 atm = 1.013 bar • Atmospheric P (1 atm at 0msw) • Absolute P (ata)= gauge P +1 atm • Absolute P = gauge P + • °F = (9/5 x °C) +32 atmospheric P • °C= 5/9 (°F – 32) • Water virtually incompressible – density remains ~same regardless • °R (rankine) = °F + 460 **absolute depth/pressure • K (Kelvin) = °C + 273 **absolute • Density salt water 1027 kg/m3 • Density fresh water 1000kg/m3 • Calculate depth from gauge pressure you divide press by 0.1027 (salt water) or 0.10000 (fresh water) Laws & Principles • All calculations require absolute units • Henry’s Law: (K, °R, ATA) • The amount of gas that will dissolve in a liquid is almost directly proportional to • Charles’ Law V1/T1 = V2/T2 the partial press of that gas, & inversely proportional to absolute temp • Guy-Lussac’s Law P1/T1 = P2/T2 • Partial Pressure (pp) – pressure • Boyle’s Law P1V1= P2V2 contributed by a single gas in a mix • General Gas Law (P1V1)/ T1 = (P2V2)/ T2 • To determine the partial pressure of a gas at any depth, we multiply the press (ata) • Archimedes' Principle x %of that gas Henry’s Law • Any object immersed in liquid is buoyed -

Middle Airway Obstructiondit May Be Happening Under Our Noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1

Thorax Online First, published on July 19, 2012 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 Chest clinic OPINION Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 on 19 July 2012. Downloaded from Middle airway obstructiondit may be happening under our noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1 < Additional materials are ABSTRACT for this conceptual error to be refuted.2 The virus is published online only. To view Background Lower airway obstruction has evolved to now understood to spread from nose to lung, and these files please visit the denote pathologies associated with diseases of the lung, appropriate recognition of the close association journal online (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/ whereas, conditions proximal to the lung embody upper between upper and lower airway pathologies has thoraxjnl-2012-202221/content/ airway obstruction. This approach has disconnected had positive outcomes. An example is novel strat- early/recent). diseases of the larynx and trachea from the lung, and egies that may not be able to prevent colds, but 1Lung and Sleep Medicine, removed the ‘middle airway’ from the interest and that could ameliorate virus asthma exacerbations Monash University and Hospital involvement of respiratory physicians and scientists. through the use of inhaled interferon.3 and Monash Institute of Medical However, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction Accumulating evidence suggests that the middle Research (MIMR), Melbourne, of this anatomical region may be a key component of Australia airway plays a key role in airway obstruction either 2Respiratory Medicine, Imperial overall airway obstruction, either independently or in independently or with coexisting lung disease. -

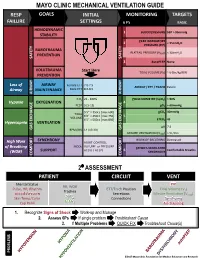

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Near Drowning

Near Drowning McHenry Western Lake County EMS Definition • Near drowning means the person almost died from not being able to breathe under water. Near Drownings • Defined as: Survival of Victim for more than 24* following submission in a fluid medium. • Leading cause of death in children 1-4 years of age. • Second leading cause of death in children 1-14 years of age. • 85 % are caused from falls into pools or natural bodies of water. • Male/Female ratio is 4-1 Near Drowning • Submersion injury occurs when a person is submerged in water, attempts to breathe, and either aspirates water (wet) or has laryngospasm (dry). Response • If a person has been rescued from a near drowning situation, quick first aid and medical attention are extremely important. Statistics • 6,000 to 8,000 people drown each year. Most of them are within a short distance of shore. • A person who is drowning can not shout for help. • Watch for uneven swimming motions that indicate swimmer is getting tired Statistics • Children can drown in only a few inches of water. • Suspect an accident if you see someone fully clothed • If the person is a cold water drowning, you may be able to revive them. Near Drowning Risk Factor by Age 600 500 400 300 Male Female 200 100 0 0-4 yr 5-9 yr 10-14 yr 15-19 Ref: Paul A. Checchia, MD - Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital Near Drowning • “Tragically 90% of all fatal submersion incidents occur within ten yards of safety.” Robinson, Ped Emer Care; 1987 Causes • Leaving small children unattended around bath tubs and pools • Drinking -

Cough and Laryngospasm Prevention During Orotracheal Extubation In

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 71 (2021) 90---95 LETTER TO THE EDITOR −1 −1 0.25 mg.kg and ketamine 0.25 mg.kg also have showed Cough and laryngospasm 4 being effective for such purpose. prevention during orotracheal The timing of extubation according to the child’s breath- extubation in children with ing cycle is another point of interest. The author of an SARS-CoV-2 infection educational review about extubation in children mentions that he extubates the child at the end of spontaneous inspi- Dear Editor, ration without suction or positive pressure, arguing that at this point the child’s lungs are full of O2-enriched air and that Little is mentioned about the importance of avoiding cough the first trans laryngeal movement of air that follows directs and laryngospasm during extubation in the Operating Room all secretions away from the laryngeal structures decreasing 5 (OR) in pediatric patients with suspected or confirmed SARS- the risk of laryngospasm. CoV-2 infection. Coughing is an important source of viral According to the former, from the perspective of respira- contagion among humans and must be considered a high-risk tory complications associated with extubation, it is safer for complication for the health workers. Laryngospasm, more the health personnel to perform the extubation to a deep frequent in children than in adults, compels to intervene anesthetized patient, during spontaneous ventilation at the with positive pressure on the patient’s airway increasing the end of inspiration and in lateral decubitus. Special attention described risk. Different from intubation in the OR, where must be given to the use of the medications described for the anesthesiologist has certain control on the procedure, coughing and laryngospasm prevention after the withdrawal extubation and emergence from anesthesia have a greater of the orotracheal tube. -

Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Exercise-induced Laryngeal Obstruction Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is a breathing problem that affects people during exercise. EILO is defined by inappropriate narrowing of the upper airway at the level of the vocal cords (glottis) and/or supraglottis (above the vocal cords). This can make it hard to get air into your lungs during exercise and cause a noisy breathing that can be frightening. EILO has also been called vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) or paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM). Most people with EILO only have symptoms when they Common signs and symptoms of EILO exercise, those some people may have the problem at During (or immediately after) high-intensity exercise, other times as well. (See ATS Patient Information Series with EILO you may experience: fact sheet ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction/Vocal Cord ■■ Profound shortness of breath or breathlessness Dysfunction’) ■■ Noisy breathing, particularly when breathing in Where are the vocal cords and what do they do? (stridor, gasping, raspy sounds, or “wheezing”) Your vocal cords are located in your upper airway or ■■ A feeling of choking or suffocation that can be scary larynx. Your supraglottic structures (including your ■■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Feeling like there is a lump in the throat arytenoid cartilages and epiglottis) are located above the ■■ Throat or chest tightness vocal cords and are part of your larynx. The larynx is often called the voice box and is deep in your throat. When These symptoms often come on suddenly during you speak, the vocal cords vibrate as you breathe out, exercise, and are typically quite noticeable or concerning to people around you as well. -

Obliterative Bronchiolitis with Atypical Features: CT Scan and Necropsy Findings

Copyright @ERS Journals Ud 1993 Eur Aespir J, 1993, 6, 1221-1225 European Respiratory Journal Printed In UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 CASE REPORT Obliterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: CT scan and necropsy findings M.I.M. Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsfield, I. Gordon, R. Heaton, W.A. Seed, A. Guz Ob/iterative bronchiolitis with atypical features: er scan and necropsy findings. M.l.M. Academic Unit of Cardiovascular Medi Noble, B. Fox, K. Horsjield, l. Gordon, R. Hearon, WA. Seed, A. Guz. ©ERS Journals cine and Depts of Medicine and Pathol l.Jd 1993. ogy, Charing Cross and Westminster ABSTRACT: We describe the natural history of cryptogenic bronchiolitis obliter Medical School. London, and the King ans in a patient foUowed for 24 yrs with serial pulmonary function tests and radi Edward VII Hospital, Midhurst, W . ology. Sussex, UK. Severe, progressive airway obstruction developed, with overinOation but preser Correspondence: M.I.M. Noble, Academic vation of Kco. There was progressive hypoxaemia, which worseroed on exertion; Unit of Cardiovascular Medicine, West hypercapnoca was modest until late in the illness. Neither bronchodilators nor ster minster Hospital, 369 Fulharn Rd, London oids were effective. The chest radiograph remained normal; CT showed irregular SWIO 9NH, UK. areas of low altentuation peripheroUy throughout the lungs, with Bounsfield nu m Keywords: Airway obstruction, bronchi bers typical of emphysema, but no bullae. Postmortem studies included histology olitis obliterans, lung diseases, obstructive and quantitative studies of a corrosion cast of one lung. They showed marked air respiratory insufficiency, pulmonary diffus way narrowing at all levels, with pruning of peripheral branches, mucus plugging, ing capacity. -

Acute Laryngeal Dystonia

Collins N, Sager J. J Neurol Neuromedicine (2018) 3(1): 4-7 Neuromedicine www.jneurology.com www.jneurology.com Journal of Neurology & Neuromedicine Mini Review Open Access Acute laryngeal dystonia: drug-induced respiratory failure related to antipsychotic medications Nathan Collins*, Jeffrey Sager Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital Department of Internal Medicine Santa Barbara, CA, USA Article Info ABSTRACT Article Notes Acute laryngeal dystonia (ALD) is a drug-induced dystonic reaction that can Received: December 10, 2017 lead to acute respiratory failure and is potentially life-threatening if unrecognized. Accepted: January 16, 2018 It was first reported in 1978 when two individuals were noticed to develop *Correspondence: difficulty breathing after administration of haloperidol. Multiple cases have since Dr. Nathan Collins MD been reported with the use of first generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and more Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital recently second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Acute dystonic reactions (ADRs) Department of Internal Medicine, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, have an occurrence rate of 3%-10%, but may occur more frequently with high Email: [email protected] potency antipsychotics. Younger age and male sex appear to be the most common risk factors, although a variety of metabolic abnormalities and illnesses have also © 2018 Collins N. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License been associated with ALD as well. The diagnosis of ALD can go unrecognized as other causes of acute respiratory failure are often explored prior to ALD. The exact mechanism for ALD remains unclear, yet evidence has shown a strong correlation with extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and dopamine receptor blockade.