An Essay in Universal History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9781501756030 Revised Cover 3.30.21.Pdf

, , Edited by Christine D. Worobec For a list of books in the series, visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. From Victory to Peace Russian Diplomacy aer Napoleon • Elise Kimerling Wirtschaer Copyright © by Cornell University e text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives . International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/./. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, East State Street, Ithaca, New York . Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Wirtschaer, Elise Kimerling, author. Title: From victory to peace: Russian diplomacy aer Napoleon / by Elise Kimerling Wirtschaer. Description: Ithaca [New York]: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, . | Series: NIU series in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian studies | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN (paperback) | ISBN (pdf) | ISBN (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Russia—Foreign relations—–. | Russia—History— Alexander I, –. | Europe—Foreign relations—–. | Russia—Foreign relations—Europe. | Europe—Foreign relations—Russia. Classication: LCC DK.W (print) | LCC DK (ebook) | DDC ./—dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Cover image adapted by Valerie Wirtschaer. is book is published as part of the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. With the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Pilot uses cutting-edge publishing technology to produce open access digital editions of high-quality, peer-reviewed monographs from leading university presses. -

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia Through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises Through Art

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography by Ihar Maslenikau B.A., Minsk, 1991 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Ihar Maslenikau 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Ihar Maslenikau Degree: Master of Arts Title: Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding of Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography Examining Committee: Chair: Gary McCarron Associate Professor, Dept. of Communication Graduate Chair, Graduate Liberal Studies Program Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor Professor Emeritus Humanities and English Heesoon Bai Supervisor Professor Faculty of Education Paul Crowe External Examiner Associate Professor Humanities and Asia-Canada Program Date Defended/Approved: November 25, 2015 ii Abstract The first essay is a sustained reflection on and response to the question of why the notion of collectivism and collective coexistence has been so deeply entrenched in the Russian society and in the Russian psyche and is still pervasive in today's Russia, a quarter of a century after the fall of communism. It examines the development of ideas of collectivism and individualism in Russian society, focusing on the cultural aspects based on the examples of selected works from Russian literature. It also searches for the answers in the philosophical works of Vladimir Solovyov, Nicolas Berdyaev and Vladimir Lossky. -

Biografije-Kandidata

Drakulić, Sanja skladateljica, pijanistica (Zagreb, 16. lipnja 1963.) Studij klavira završila 1986. na Muzičkoj akademiji u Zagrebu (prof. P. Gvozdić), a usavršavala se u inozemstvu (J.–M. Darré, S. Popovici, R. Kehrer). Kompoziciju je počela učiti na MA u Zagrebu kod prof. Stanka Horvata, a nastavila u Moskvi. Studij kompozicije s poslijediplomskom specijalizacijom završila je na Moskovskom državnom konzervatoriju P. I. Čajkovski (A. Pirumov, J. Bucko), gdje je studirala i muzikologiju (E. Gordina) i orgulje (O. Jančenko) te bila asistent. Od 1995. radila je kao redovita profesorica na Visokoj školi za glazbenu umjetnost Ino Mirković u Lovranu, a potom je djelovala kao slobodna umjetnica. Od 2000. radi na Umjetničkoj akademiji Sveučilišta J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku. Održava međunarodne tečajeve i seminare iz kompozicije i teorije (Europa, Amerika, Japan). Angažirana je u žirijima međunarodnih natjecanja. Piše za Cantus i druge novine. Bila je voditeljica Međunarodne glazbene tribine u Puli. Djela joj izvode priznati svjetski i hrvatski solisti i sastavi na međunarodnim festivalima suvremene glazbe, u koncertnim dvoranama Hrvatske, Bosne i Hercegovine, Njemačke, Rusije, Ukrajine, Italije, Njemačke, SAD–a i Japana. Kao pijanistica nastupa po Europi i Sjedinjenim Američkim Državama. Članica je Hrvatskog društva skladatelja, Saveza skladatelja Rusije i Britanske akademije skladatelja i pjesnika. Nagrade: Na Sveruskom natjecanju mladih kompozitora u Moskvi (1993.) osvojila je prvu nagradu s kompozicijom Pet intermezza za klavir solo. Dobitnica je Jeljcinove Predsjednikove stipendije za skladatelje i brojnih nagrada za skladbe: nagrade Ministarstva kulture Ruske Federacije, te hrvatske nagrade Ministarstva kulture RH za poticanje glazbenog stvaralaštva, Hrvatskog sabora kulture, festivala Naš kanat je lip, Matetićevi dani, Cro patria i drugih. -

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark

1848 Revolutions Special Subject I READING LIST Professor Chris Clark The Course consists of 8 lectures, 16 presentation-led seminars and 4 gobbets classes GENERAL READING Jonathan Sperber, The European Revolutions, 1848-1851 (Cambridge, 1994) Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Oxford, 2001) Priscilla Smith Robertson, The Revolutions of 1848, a social history (Princeton, 1952) Michael Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (London, 2009) SOCIAL CONFLICT BEFORE 1848 (i) The ‘Galician Slaughter’ of 1846 Hans Henning Hahn, ‘The Polish Nation in the Revolution of 1846-49’, in Dieter Dowe et al., eds., Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform, pp. 170-185 Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford, 2010), esp. chapters 3 & 4 Thomas W. Simons Jr., ‘The Peasant Revolt of 1846 in Galicia: Recent Polish Historiography’, Slavic Review, 30 (December 1971) pp. 795–815 (ii) Weavers in Revolt Robert J. Bezucha, The Lyon Uprising of 1834: Social and Political Conflict in the Early July Monarchy (Cambridge Mass., 1974) Christina von Hodenberg, Aufstand der Weber. Die Revolte von 1844 und ihr Aufstieg zum Mythos (Bonn, 1997) *Lutz Kroneberg and Rolf Schloesser (eds.), Weber-Revolte 1844 : der schlesische Weberaufstand im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Publizistik und Literatur (Cologne, 1979) Parallels: David Montgomery, ‘The Shuttle and the Cross: Weavers and Artisans in the Kensington Riots of 1844’ Journal of Social History, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Summer, 1972), pp. 411-446 (iii) Food riots Manfred Gailus, ‘Food Riots in Germany in the Late 1840s’, Past & Present, No. 145 (Nov., 1994), pp. 157-193 Raj Patel and Philip McMichael, ‘A Political Economy of the Food Riot’ Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 32/1 (2009), pp. -

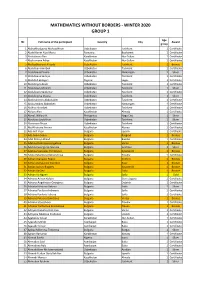

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abboskhodjaeva Mohasalkhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdel Karim Alya Maria Romania Bucharest 1 Certificate 3 Abdraimov Alan Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 4 Abdraimova Adiya Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 5 Abdujabborova Alizoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdullaev Amirbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdullaeva Dinara Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 8 Abdullaeva Samiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdullah Balogun Nigeria Lagos 1 Certificate 10 Abdullayev Azam Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdullayev Mirolim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 12 Abdullayev Saidumar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abdullayeva Diyora Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 14 Abdurahimov Abduhakim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Abduvosidov Abbosbek Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 16 Abidov Islombek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 17 Abiyev Alan Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 18 Abriol, Willary A. Philippines Naga City 1 Silver 19 Abrolova Laylokhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 20 Abrorova Afruza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 21 Abulkhairova Amina Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Certificate 22 Ada Arif Vasvi Bulgaria Isperih 1 Certificate 23 Ada Selim Selim Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Bronze 24 Adel Dzheyn Brand Bulgaria Bansko 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Dobrinova Angelova Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 26 Adelina Georgieva Ivanova Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Silver 27 Adelina Svetoslav Yordanova Bulgaria Kyustendil 1 Bronze 28 Adina Zaharieva -

Voices of Children

VOICES OF CHILDREN SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA, 2017 SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA 01 2017 This report was prepared as per UNICEF Bulgaria assignment. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF. This report should be quoted in any reprint, in whole or in part. VOICES OF CHILDREN Survey of the Opinion of Children and Young People in Bulgaria, 2017 © 2018 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Permission is required to reproduce the text of this publication. Please contact the Communication section of UNICEF in Bulgaria, tel.: +359 2/ 9696 208. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Blvd Dondukov 87, fl oor 2 Sofia 1054, Bulgaria For further information, please visit the UNICEF Bulgaria website at www.unicef.org/bulgaria SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA 02 2017 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................2 2. Methodological Note .....................................................................................................................5 3. How happy are Bulgarian children? ............................................................................................10 3.1. Self-Assessment .................................................................................................................12 3.2. Moments when children feel -

Russia and Asia: the Emerging Security Agenda

Russia and Asia The Emerging Security Agenda Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent international institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of arms control and disarmament. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden’s 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed mainly by the Swedish Parliament. The staff and the Governing Board are international. The Institute also has an Advisory Committee as an international consultative body. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Professor Daniel Tarschys, Chairman (Sweden) Dr Oscar Arias Sánchez (Costa Rica) Dr Willem F. van Eekelen (Netherlands) Sir Marrack Goulding (United Kingdom) Dr Catherine Kelleher (United States) Dr Lothar Rühl (Germany) Professor Ronald G. Sutherland (Canada) Dr Abdullah Toukan (Jordan) The Director Director Dr Adam Daniel Rotfeld (Poland) Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Signalistg. 9, S-1769 70 Solna, Sweden Cable: SIPRI Telephone: 46 8/655 97 00 Telefax: 46 8/655 97 33 E-mail: [email protected] Internet URL: http://www.sipri.se Russia and Asia The Emerging Security Agenda Edited by Gennady Chufrin OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1999 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens -

No Song to Sing

c/ Enrique Granados, 49, SP. 08008 Barcelona T. (+34) 93 451 0064, [email protected] http://www.adngaleria.com No song to sing A project curated by David Armengol and Martí Manen ADN Platform. November 2015 – April 2016 Johanna Billing / Bradien + Eduard Escoffet / Lucía C. Pino / Carles Congost / Laia Estruch / Antoni Hervàs / Pepo Salazar / Tris Vonna-Michell / Richard T. Walker / Franziska Windisch Carles Congost, Mystical Drummer, 2013 The point of departure for No Song to Sing starts with two songs belonging to pop culture: a homonymous theme composed by the English musician Michael Chapman for Rainwater (1969), his first album; and one of Stevie Wonder’s most celebrated hits, I Just Called to Say I Love You (1984). In both cases, the songs opposing relation between absence and presence produces a conceptual ambiguity that relates, in a poetic way, with the sound productions of contemporary art. Initially, a big table equipped with several listening devices makes the audio pieces available to the user. This allows us to recreate and assume some domestic musical consumption habits: a record player, a CD player, a computer and headphones. Then, each of the sound proposals expands into other special and visual productions. In some situations, they are closely related to the pieces on the table; at others, however, all linkage gets severed in order to show new work sensitive to sound and adapted to art exhibition practices. Orfeo y la Montaña Sumergida [Orpheus and the Sunken Mountain] (2014) is a project by Antoni Hervàs (Barcelona, 1981) which is dedicated to one of his fetish subjects: the reenactment of the mermaid myth through performance and the staging power of drawing. -

251 Chapter IX Revolution And

251 Chapter IX Revolution and Law (1789 – 1856) The Collapse of the European States System The French Revolution of 1789 did not initialise the process leading to the collapse of the European states system but accelerated it. In the course of the revolution, demands became articulate that the ruled were not to be classed as subjects to rulers but ought to be recognised as citizens of states and members of nations and that, more fundamentally, the continuity of states was not a value in its own right but ought to be measured in terms of their usefulness for the making and the welfare of nations. The transformations of groups of subjects into nations of citizens took off in the political theory of the 1760s. Whereas Justus Lipsius and Thomas Hobbes1 had described the “state of nature” as a condition of human existence that might occur close to or even within their present time, during the later eighteenth century, theorists of politics and international relations started to position that condition further back in the past, thereby assuming that a long period of time had elapsed between the end of the “state of nature” and the making of states and societies, at least in some parts of the world. Moreover, these theorists regularly fused the theory of the hypothetical contract for the establishment of government, which had been assumed since the fourteenth century, with the theory of the social contract, which had only rarely been postulated before.2 In the view of later eighteenth-century theorists, the combination of both types of contract was to establish the nation as a society of citizens.3 Supporters of this novel theory of the combined government and social contract not merely considered human beings as capable of moving out from the “state of nature” into states, but also gave to humans the discretional mandate to first form their own nations as what came to be termed “civil societies”, before states could come into existence.4 Within states perceived in accordance with these theoretical suppositions, nationals remained bearers of sovereignty. -

Higher Education Reform in the Balkans: Using the Bologna Process

23 The AVCC data also include valuable information on mode of delivery. For example, the data show that Higher Education Reform in less than 17 percent of Australian offshore programs in the Balkans: Using the China included a period of study in Australia. Just over 25 percent include at least some study by distance Bologna Process learning, while only 15 percent are offered wholly at a Anthony W. Morgan distance. The AVCC data give no details on enrollments. Anthony Morgan is professor of educational leadership and policy and In the second Observatory report, 20 Sino-foreign special assistant to the president at the University of Utah. Address: education partnerships were selected for analysis, Dept. of Educ. Leaadership, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, covering nine countries and six categories of activity. As USA. Email: [email protected]. would be expected, almost all activity began following the 1995 regulations, and there is evidence over time of ike many other regions in transition, countries in the more ambition and greater commitment on the part of LBalkans are struggling with higher education reform joint ventures—moving from joint centers and programs due at least in part to academic cultural traditions and to branch campuses. Both the University of Nottingham organizational structures. Change comes hard here de- in the United Kingdom and Oklahoma City University spite very difficult financial circumstances that some- from the United States were expressly invited by the times provide opportunities for reform. But national authorities to set up operations in China, governmental and institutional aspirations for change marking the first official push in this direction. -

Roma As Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania

Roma as Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Roderick Charles Lawford DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated, and the thesis has not been edited by a third party beyond what is permitted by Cardiff University’s Policy on the Use of Third Party Editors by Research Degree Students. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… ii To Sue Lawford and In Memory of Marion Ethel Lawford (1924-1977) and Charles Alfred Lawford (1925-2010) iii Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Plates vii List of Tables ix Conventions x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - Theory and Method -

History of International Relations

3 neler öğrendik? bölüm özeti History of International Relations Editors Dr. Volkan ŞEYŞANE Evan P. PHEIFFER Authors Asst.Prof. Dr. Murat DEMİREL Dr. Umut YUKARUÇ CHAPTER 1 Prof.Dr. Burak Samih GÜLBOY Caner KUR CHAPTER 2, 3 Asst.Prof.Dr. Seçkin Barış GÜLMEZ CHAPTER 4 Assoc.Prof.Dr. Pınar ŞENIŞIK ÖZDABAK CHAPTER 5 Asst.Prof.Dr. İlhan SAĞSEN Res.Asst. Ali BERKUL Evan P. PHEIFFER CHAPTER 6 Dr. Çağla MAVRUK CAVLAK CHAPTER 7 Prof. Dr. Lerna K. YANIK Dr. Volkan ŞEYŞANE CHAPTER 8 T.C. ANADOLU UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION NO: 3920 OPEN EDUCATION FACULTY PUBLICATION NO: 2715 Copyright © 2019 by Anadolu University All rights reserved. This publication is designed and produced based on “Distance Teaching” techniques. No part of this book may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means of mechanical, electronic, photocopy, magnetic tape, or otherwise, without the written permission of Anadolu University. Instructional Designer Lecturer Orkun Şen Graphic and Cover Design Prof.Dr. Halit Turgay Ünalan Proof Reading Lecturer Gökhan Öztürk Assessment Editor Lecturer Sıdıka Şen Gürbüz Graphic Designers Gülşah Karabulut Typesetting and Composition Halil Kaya Dilek Özbek Gül Kaya Murat Tambova Beyhan Demircioğlu Handan Atman Kader Abpak Arul HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS E-ISBN 978-975-06-3603-5 All rights reserved to Anadolu University. Eskişehir, Republic of Turkey, October 2019 3328-0-0-0-1909-V01 Contents The Emergence The International of the Modern System During CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 th International the Long 19 System Century Introduction ................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................. 29 History of the State System: From The Revolutions and the International System .