Voices of Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biografije-Kandidata

Drakulić, Sanja skladateljica, pijanistica (Zagreb, 16. lipnja 1963.) Studij klavira završila 1986. na Muzičkoj akademiji u Zagrebu (prof. P. Gvozdić), a usavršavala se u inozemstvu (J.–M. Darré, S. Popovici, R. Kehrer). Kompoziciju je počela učiti na MA u Zagrebu kod prof. Stanka Horvata, a nastavila u Moskvi. Studij kompozicije s poslijediplomskom specijalizacijom završila je na Moskovskom državnom konzervatoriju P. I. Čajkovski (A. Pirumov, J. Bucko), gdje je studirala i muzikologiju (E. Gordina) i orgulje (O. Jančenko) te bila asistent. Od 1995. radila je kao redovita profesorica na Visokoj školi za glazbenu umjetnost Ino Mirković u Lovranu, a potom je djelovala kao slobodna umjetnica. Od 2000. radi na Umjetničkoj akademiji Sveučilišta J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku. Održava međunarodne tečajeve i seminare iz kompozicije i teorije (Europa, Amerika, Japan). Angažirana je u žirijima međunarodnih natjecanja. Piše za Cantus i druge novine. Bila je voditeljica Međunarodne glazbene tribine u Puli. Djela joj izvode priznati svjetski i hrvatski solisti i sastavi na međunarodnim festivalima suvremene glazbe, u koncertnim dvoranama Hrvatske, Bosne i Hercegovine, Njemačke, Rusije, Ukrajine, Italije, Njemačke, SAD–a i Japana. Kao pijanistica nastupa po Europi i Sjedinjenim Američkim Državama. Članica je Hrvatskog društva skladatelja, Saveza skladatelja Rusije i Britanske akademije skladatelja i pjesnika. Nagrade: Na Sveruskom natjecanju mladih kompozitora u Moskvi (1993.) osvojila je prvu nagradu s kompozicijom Pet intermezza za klavir solo. Dobitnica je Jeljcinove Predsjednikove stipendije za skladatelje i brojnih nagrada za skladbe: nagrade Ministarstva kulture Ruske Federacije, te hrvatske nagrade Ministarstva kulture RH za poticanje glazbenog stvaralaštva, Hrvatskog sabora kulture, festivala Naš kanat je lip, Matetićevi dani, Cro patria i drugih. -

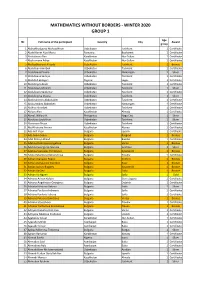

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abboskhodjaeva Mohasalkhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdel Karim Alya Maria Romania Bucharest 1 Certificate 3 Abdraimov Alan Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 4 Abdraimova Adiya Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 5 Abdujabborova Alizoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdullaev Amirbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdullaeva Dinara Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 8 Abdullaeva Samiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdullah Balogun Nigeria Lagos 1 Certificate 10 Abdullayev Azam Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdullayev Mirolim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 12 Abdullayev Saidumar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abdullayeva Diyora Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 14 Abdurahimov Abduhakim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Abduvosidov Abbosbek Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 16 Abidov Islombek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 17 Abiyev Alan Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 18 Abriol, Willary A. Philippines Naga City 1 Silver 19 Abrolova Laylokhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 20 Abrorova Afruza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 21 Abulkhairova Amina Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Certificate 22 Ada Arif Vasvi Bulgaria Isperih 1 Certificate 23 Ada Selim Selim Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Bronze 24 Adel Dzheyn Brand Bulgaria Bansko 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Dobrinova Angelova Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 26 Adelina Georgieva Ivanova Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Silver 27 Adelina Svetoslav Yordanova Bulgaria Kyustendil 1 Bronze 28 Adina Zaharieva -

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk Kunstner Listen

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk kunstner Listen Stacy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stacy-3503566/albums The Idan Raichel Project https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/the-idan-raichel-project-12406906/albums Mig 21 https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mig-21-3062747/albums Donna Weiss https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/donna-weiss-17385849/albums Ben Perowsky https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ben-perowsky-4886285/albums Ainbusk https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ainbusk-4356543/albums Ratata https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ratata-3930459/albums Labvēlīgais Tips https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/labv%C4%93l%C4%ABgais-tips-16360974/albums Deane Waretini https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/deane-waretini-5246719/albums Johnny Ruffo https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/johnny-ruffo-23942/albums Tony Scherr https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tony-scherr-7823360/albums Camille Camille https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/camille-camille-509887/albums Idolerna https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/idolerna-3358323/albums Place on Earth https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/place-on-earth-51568818/albums In-Joy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/in-joy-6008580/albums Gary Chester https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gary-chester-5524837/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums -

No Song to Sing

c/ Enrique Granados, 49, SP. 08008 Barcelona T. (+34) 93 451 0064, [email protected] http://www.adngaleria.com No song to sing A project curated by David Armengol and Martí Manen ADN Platform. November 2015 – April 2016 Johanna Billing / Bradien + Eduard Escoffet / Lucía C. Pino / Carles Congost / Laia Estruch / Antoni Hervàs / Pepo Salazar / Tris Vonna-Michell / Richard T. Walker / Franziska Windisch Carles Congost, Mystical Drummer, 2013 The point of departure for No Song to Sing starts with two songs belonging to pop culture: a homonymous theme composed by the English musician Michael Chapman for Rainwater (1969), his first album; and one of Stevie Wonder’s most celebrated hits, I Just Called to Say I Love You (1984). In both cases, the songs opposing relation between absence and presence produces a conceptual ambiguity that relates, in a poetic way, with the sound productions of contemporary art. Initially, a big table equipped with several listening devices makes the audio pieces available to the user. This allows us to recreate and assume some domestic musical consumption habits: a record player, a CD player, a computer and headphones. Then, each of the sound proposals expands into other special and visual productions. In some situations, they are closely related to the pieces on the table; at others, however, all linkage gets severed in order to show new work sensitive to sound and adapted to art exhibition practices. Orfeo y la Montaña Sumergida [Orpheus and the Sunken Mountain] (2014) is a project by Antoni Hervàs (Barcelona, 1981) which is dedicated to one of his fetish subjects: the reenactment of the mermaid myth through performance and the staging power of drawing. -

Higher Education Reform in the Balkans: Using the Bologna Process

23 The AVCC data also include valuable information on mode of delivery. For example, the data show that Higher Education Reform in less than 17 percent of Australian offshore programs in the Balkans: Using the China included a period of study in Australia. Just over 25 percent include at least some study by distance Bologna Process learning, while only 15 percent are offered wholly at a Anthony W. Morgan distance. The AVCC data give no details on enrollments. Anthony Morgan is professor of educational leadership and policy and In the second Observatory report, 20 Sino-foreign special assistant to the president at the University of Utah. Address: education partnerships were selected for analysis, Dept. of Educ. Leaadership, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, covering nine countries and six categories of activity. As USA. Email: [email protected]. would be expected, almost all activity began following the 1995 regulations, and there is evidence over time of ike many other regions in transition, countries in the more ambition and greater commitment on the part of LBalkans are struggling with higher education reform joint ventures—moving from joint centers and programs due at least in part to academic cultural traditions and to branch campuses. Both the University of Nottingham organizational structures. Change comes hard here de- in the United Kingdom and Oklahoma City University spite very difficult financial circumstances that some- from the United States were expressly invited by the times provide opportunities for reform. But national authorities to set up operations in China, governmental and institutional aspirations for change marking the first official push in this direction. -

Roma As Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania

Roma as Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Roderick Charles Lawford DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated, and the thesis has not been edited by a third party beyond what is permitted by Cardiff University’s Policy on the Use of Third Party Editors by Research Degree Students. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… Date ………………………… ii To Sue Lawford and In Memory of Marion Ethel Lawford (1924-1977) and Charles Alfred Lawford (1925-2010) iii Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Plates vii List of Tables ix Conventions x Acknowledgements xii Abstract xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 - Theory and Method -

Trouble Followed Winamp\2 Pac - Trouble Followed.Mp3 #Extinf:241,2Pac/Dr

#extm3u #extinf:207,morandi - beijo (uh-la-la) winamp\18 18 track 18.wma #extinf:153,2 pac - trouble followed winamp\2 pac - trouble followed.mp3 #extinf:241,2pac/dr. dre/roger troutman - california love winamp\2pac & dr dre - california love.mp3 #extinf:302,2pac, nas & obie trice - 3 messages winamp\2pac & nas and obie trice - 3 messages.mp3 #extinf:243,2pac - thugs get lonely too winamp\2pac - thugs get lonely too.mp3 #extinf:113,2pac vs limp bizkit, meth, redman, dmx - all about u (skylar johnson remix) winamp\2pac vs limp bizkit, meth, redman, dmx - all about u (skylar johnson remix).mp3 #extinf:238,2pac - ghetto gospel feat. elton john winamp\2pac-ghetto_gospel_feat._elton_john_(prod_by_eminem)-mob.mp3 #extinf:197,2pac - hennessey feat. e.d.i. of the winamp\2pac-hennessey_feat._e.d.i._of_the_outlawz_and_sleepy_bro.mp3 #extinf:16,50cent eminem cashis and lloyd banks-you dont know winamp\50cent_eminem_cashis_and_lloyd_banks-you_dont_know.mp3 #extinf:230,abba - dancing queen winamp\abba - dancing queen.mp3 #extinf:241,abba - knowing me knowing you winamp\abba - knowing me knowing you.mp3 #extinf:210,abba - mamma mia winamp\abba - mamma mia.mp3 #extinf:185,abba - money, money, money winamp\abba - money, money, money.mp3 #extinf:250,abba - super trouper winamp\abba - super trouper.mp3 #extinf:349,abba - the day before you came winamp\abba - the day before you came.mp3 #extinf:294,abba - the winner takes it all winamp\abba - the winner takes it all.mp3 #extinf:289,abba - gimme gimme gimme winamp\abba_-_gimme_gimme_gimme.mp3 #extinf:220,abba -

“Perverting the Taste of the People”: Lăutari and the Balkan Question in Romania ______

DOI https://doi.org/10.2298/MUZ2029085L UDC 784.4(=214.58)(498) “Perverting the Taste of the People”: Lăutari and the Balkan Question in Romania ___________________________ Roderick Charles Lawford1 Cardiff University, United Kingdom „Извитоперење укуса људи“: Lăutari и балканско питање у Румунији __________________________ Родерик Чарлс Лофорд Универзитет у Кардифу, Уједињено Краљевство Received: 1 September 2020 Accepted: 9 November 2020 Original scientific article. Abstract “’Perverting the Taste of the People’: Lăutari and the Balkan Question in Ro- mania” considers the term “Balkan” in the context of Romanian Romani mu- sic-making. The expression can be used pejoratively to describe something “bar- baric” or fractured. In the “world music” era, “gypsy-inspired” music from the Balkans has become highly regarded. From this perspective “Balkan” is seen as something desirable. The article uses the case of the Romanian “gypsy” band Taraf de Haïdouks in illustration. Romania’s cultural and physical position with- in Europe can be difficult to locate, a discourse reflected in Romanian society itself, where many reject the description of Romania as a “Balkan” country. This conflict has been contested throughmanele , a Romanian popular musical genre. In contrast, manele is seen by its detractors as too “eastern” in character, an unwel- come reminder of earlier Balkan and Ottoman influences on Romanian culture. Keywords: Balkan(s), Romania, alterity, exotic, oriental, Ottoman, manele, lăutari, “gypsy”, Turkish, Roma, Romani, “world music”, subaltern. 1 [email protected] 86 МУЗИКОЛОГИЈА / MUSICOLOGY 29-2020 Апстракт „’Извитоперење укуса људи’: Lăutari и балканско питање у Румунији“ студија је у којој се разматра појам „Балкан“ у контексту музичке продукције румунских Рома. -

New Folk: the Phenomenon of Chalga in Modern Bulgarian Folk

New Folk: The phenomenon of chalga in modern Bulgarian folk “Edno ferari s zviat cherven, edno za teb, edno za men…” Slavi Trifonov, chalga (One red Ferrari, one for me, one for you) ©2004 Milena Droumeva Milena Droumeva Term Paper, page 1 They were silly, kitsch, synthesized tunes, which started appearing in Bulgarian media, and in the general Bulgarian cultural life in the early 1990s. Now, chalga has successfully found a niche in the Bulgarian music scene with a new image and a new name: pop folk. Initially characterized by simplistic lyrics and ‘oriental’ street sound, chalga tunes have become more popular in a few short years than any other developing music genre in Bulgaria. It is no coincidence that some of the first and most popular chalga singers and musicians were Roma 1 or ethnic Turks. These two minority groups have distinct musical roots, very different from Bulgarian folk, which were suppressed by the state for over 45 years during the communist regime. Today, in a seemingly democratic environment, music styles in Bulgaria are thriving and folk music is reclaiming new ground after years of state control. I have to admit, I, too, was one of the skeptic connoisseurs of classical and Western popular music, who thought chalga was a low-culture Gypsy genre unworthy of attention. Having now been away from Bulgaria for four years and being immersed in Vancouver’s diverse music scene, I have gained a more rounded cosmopolitan perspective on music. I don’t see chalga or even Bulgarian folk as sporadic unrelated music genres anymore , but as interdependent events, richly influenced by each other, as well as by the music of Turkey, Greece and the rest of the Balkans. -

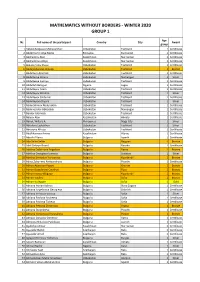

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abboskhodjaeva Mohasalkhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdel Karim Alya Maria Romania Bucharest 1 Certificate 3 Abdraimov Alan Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 4 Abdraimova Adiya Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 1 Certificate 5 Abduhamidov Zhasur Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 6 Abdujabborova Alizoda Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 7 Abdullaev Amirbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 8 Abdullaeva Dinara Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 9 Abdullaeva Samiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 10 Abdullah Balogun Nigeria Lagos 1 Certificate 11 Abdullayev Azam Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 12 Abdullayev Mirolim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 13 Abdullayev Saidumar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 14 Abdullayeva Diyora Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 15 Abdurahimov Abduhakim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 16 Abduvosidov Abbosbek Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 17 Abidov Islombek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 18 Abiyev Alan Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 19 Abriol, Willary A. Philippines Naga City 1 Silver 20 Abrolova Laylokhon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 21 Abrorova Afruza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 22 Abulkhairova Amina Kazakhstan Atyrau 1 Certificate 23 Ada Arif Vasvi Bulgaria Isperih 1 Certificate 24 Ada Selim Selim Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Bronze 25 Adel Dzheyn Brand Bulgaria Bansko 1 Certificate 26 Adelina Dobrinova Angelova Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 27 Adelina Georgieva Ivanova Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Silver 28 Adelina Svetoslav -

Ottoman Intimacies, Balkan Musical Realities. Edited by Risto Pekka

198 MUSICultures 41/2 Ottoman Intimacies, Balkan Musical way; indeed, the discourse here, and in Realities. Edited by Risto Pekka some later chapters, seems almost as lab- Pennanen, Panagiotis C. Poulos and yrinthine and contradictory as the topics Aspasia Theodosiou. 2013. Helsinki: themselves. Nevertheless, there is never Foundation of the Finnish Institute at any lack of information to process and Athens. xxx+173 pp. ideas to consider. The chapters are grouped into JUDITH COHEN three sections: “Imperial Musical Worlds York University and their Peripheries,” “Ottoman Pasts, Representations and the Performing Arts” The musical world of the former and “Ottoman Echoes and the Current Ottoman Empire and the Balkans is a Mediaspace.” One might quibble about complex one, inextricably linked to such whether “performing arts” and “medias- different phenomena as the intricacies of pace” should be in different sections, but, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian history, then again, one can always argue for re- and the current appropriation of “Gypsy arranging sections and chapters—or for music.” The essays in this volume, which not having any sections at all. originated in a conference held in Athens Cem Behar opens the first section in 2010, explore aspects of the edgy re- with a discussion of how orality and lit- lationships among Ottoman and Balkan eracy are interwoven in sometimes unex- musical worlds, and the “intimacies” of pected contexts, reflecting on the absence the authors with their topics often offer of “original” or “global” versions. Perhaps valuable insights into these and many Maureen Jackson’s fine volume (Jackson other issues. 2013) on Jewish paraliturgical singing Walter Zev Feldman opens the in Turkey had not yet appeared when he volume with a brief, thoughtful fore- wrote his chapter; several issues that he word, drawing on his expertise in discusses also appear there, though in dif- Ottoman and Balkan musical traditions, ferent contexts, and one can imagine a as well as political, historical and social fruitful dialogue. -

Ally Hand Weapons Designed for Use Against Armor

University of Massachusetts Boston The University Mace Symbols of authority and power, maces were originally hand weapons designed for use against armor. Topped by the flame of knowledge, the University mace has the University seal as a focal point and unifying element. Tassels of maroon and white hang from the shaft of fourteen rods of black walnut, symbolizing the fourteen counties of the Commonwealth. The head of the mace is gold plate over highly polished brass. Complex curves radiating from the hub in which the seal is centered reflect light in constantly changing patterns, symbolic of the many-faceted environment of the university life. Academic Costume and Regalia The academic regalia worn by faculty and students at this ceremony repre sent traditions which come down from the Middle Ages, when European universities were institutions of the church. At that time, robes were a common form of dress, particularly for officials of church and state. The cut of the robe, its adornment, and the colors used comprised a specialized heraldry that conveyed the rank and station of the wearer. At the universities, both faculty and students were considered to be part of the church hierarchy and were expected to wear the prescribed gowns. As society moved toward more modern forms of dress, only royalty, clergy, judges, and academics retained the traditional regalia, reserving it only for ceremonial use. Modern academic regalia retain some of the symbols of the earlier forms of ceremonial dress. The gown tends to be fullest, longest, and heaviest for the doctoral degree. The sleeves for the bachelor's and master's gowns are typi cally open at the wrist.