Roma As Alien Music and Identity of the Roma in Romania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manelele Ca Underground Pop. O Radiografie a Scenei Bucureștene

Primăria Municipiului București MANELELE CA UNDERGROUND POP. O RADIOGRAFIE A SCENEI BUCUREȘTENE ANAliză de ADRIAN SCHIOP Realizată la comanda ARCUB, în cadrul procesului de elaborare a Strategiei Culturale a Municipiului București (2015) Realizat sub coordonarea MANELELE CA UNDERGROUND POP. O RADIOGRAFIE A SCENEI BUCUREȘTENE În ciuda denigrării constante de care au avut parte în România, manelele au intrat de curând într-o eră a profesionalizării (industria are canale tv, case de producții proprii și localuri specializate) și în sfera cool-ului, fiind valorificate de evenimentele clasei creative bucureștene. Industria se autosusține economic și este racordată la evoluția scenelor europene de etnopop, de la care primește și trimite influențe, iar artiștii români din domeniu colaborează cu alții de pe scene similare din Balcani. Cu toate astea, genul muzical este în continuare ghetoizat și suferă de o percepție negativă din partea publicului și a autorităților, în ciuda avantajelor pe care le promit manelele: savoare locală pentru turiștii occidentali în căutare de exotic, promovarea unor valori comunitare (familie, onoare), capaci- tatea de a reda realități sociale și de a combate rasismul și elitismul societății. Pentru a le scutura de stigmă și a le permite să îndeplinească aceste misiuni, autoritățile publice pot face eforturi de reabilitare a manelelor ca gen muzical, prin care să modifice percepția elitistă cum că ele ar reprezenta muzica proștilor și să sporească self-esteem-ul publicului lor marginal, precum și să înlăture din aspectele negative asociate genului (calitatea uneori slabă a producțiilor, materialismul exacerbat al domeniului, conexiunea artiștilor cu lumea interlopă etc.). DEFINIREA MANELELOR ȘI ÎNCADRAREA LOR CA GEN MUZICAL n primul rând, trebuie spus că manelele, pop/dance, acest lucru se datorează unor factori ca gen muzical, au o structură de ianus sociologici din afară (rasism structural, elitism, bifrons. -

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

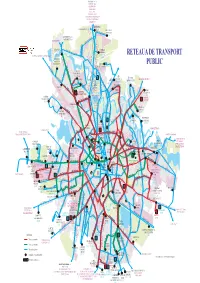

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

2019 Spring Newsletter

May 2019 www.society4romanianstudies.org Vol 41 Spring 2019 No. 1 From the President In this issue... This year’s big news is the launch of the From the President………………………………..1 Journal of Romanian Studies. The first issue is already available and the Member Announcements……………………..2 second has been sent to the Interview with Rodica Milena……………….3 publishers. Members receive an Interview with Adina Mocanu………………5 electronic subscription to the Soundbite from Romania: Economics….7 journal as part of their Soundbite from Romania: Art……………….9 membership, and others can take 2019 Romanian Studies Conference...11 out individual or institutional subscriptions by writing directly SRS-Polirom Book Series……………………12 to the publisher at Featured Books……..……………………………..14 [email protected]. Our new H-Romania……………………………………………15 membership fees reflect the cost of Advice for Young Scholars with providing the journal to our members, but also include a Monica Ciobanu…………………………………...16 discount option for graduate students and scholars from Featured Affiliate Organization…………..19 Eastern Europe. The new journal is a substantial contribution to the field, and we hope that it will stimulate some useful informed SRS Fifth Biennial Book Prize……………..20 and interdisciplinary conversations in the years ahead. SRS 2019 Grad Essay Prize………………..20 SRS Membership………………………………….21 We are also pleased to announce the latest edition to the SRS/Polirom Book Series. Diana Dumitru’s Vecini în vremuri de About SRS…………………………………………….21 restriște. Stat, antisemitism și Holocaust în Basarabia și Transnistria is now available in a translation by Miruna Andriescu (see page 10 of this newsletter for details). Romanian translations of Maria Bucur’s Heroes and Victims (2010) and the collected volume Manele in Romania (2016), edited by Margaret Beissinger, Speranța Rădulescu, and Anca Giurchescu are both under preparation. -

Lista Unităţilor Scolare Din Judeţul Giurgiu Si Circumscriptiile Arondate

LISTA UNIT ĂŢ ILOR SCOLARE DIN JUDE ŢUL GIURGIU SI CIRCUMSCRIPTIILE ARONDATE PENTRU RECENSAMANTUL COPIILOR IN VEDEREA INSCRIERII IN CLASA PREGATITOARE/CLASA I Pentru anul şcolar 2012/2013 Nr. Localitatea Denumire scoala Cicumscriptii recensamant crt. Com./ oras 1. Adunatii Sc.I-VIII Ad.Copaceni* Comuna Aduna ţii Cop ăceni, Sat Mogo şeşti Sat Varlaam Copaceni Sc.I-VIII Darasti Sat D ărăş ti, comuna Aduna ţii Cop ăceni, 2. Baneasa Sc.I-VIII Baneasa* Comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Frasinu Sat Frasinu, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Meletie Sat Meletie, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-VIII Pietrele Sat Pietrele, comuna B ăneasa, Grad.Sf. Gheorghe Sat Sf. Gheorghe, comuna B ăneasa, Sc.I-IV Baneasa Comuna B ăneasa, 3. Bolintin Sc.I-VIII Bolintin Deal* Comuna Bolintin Deal, Deal Sc.I-VIII Mihai Voda Sat Mihai Vod ă, comuna Bolintin Deal, 4. Bolintin Sc.I-VIII Bolintin Vale* Ora ş Bolintin Vale, Vale Sc.I-VIII Malu Spart Sat Malu Spart, Sc.I-IV Suseni Sat Suseni 5. Buturugeni Sc.I-VIII Buturugeni* Comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-VIII Padureni Sat P ădureni, comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-IV Prisiceni Sat Prisiceni, comuna Buturugeni, Sc.I-IV Posta Sat Po şta, comuna Buturugeni, 6. Bucsani Sc.I-VIII Bucsani* Comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-VIII Vadu Lat Sat Vadu Lat, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Uiesti Sat Uie şti, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Podisor Sat Podi şor, comuna Buc şani, Sc.I-IV Goleasca Sat Goleasca, comuna Buc şani, 7. Bulbucata Sc.I-VIII Bulbucata* Comuna Bulbucata, 8. -

Documente Muzicale Tipărite Şi Audiovizuale

BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI BIBLIOGRAFIA NA ŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale Bibliografie elaborată pe baza publicaţiilor din Depozitul Legal Anul XLVII 2014 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României BIBLIOGRAFIA NAŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ SERII ŞI PERIODICITATE Cărţi. Albume. Hărţi: bilunar Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale : anual Articole din publicaţii seriale. Cultură: lunar Publicaţii seriale: anual Românica: anual Teze de doctorat: semestrial © Copyright 2014 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din această lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, prin mijloc mecanic sau electronic sau stocat într-o bază de date, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. Înlocuieşte seria Note muzicale. Discuri. Casete Redactor: Raluca Bucinschi Coperta: Constantin Aurelian Popovici Lista pubLicaţiiLor bibLiotecii NaţioNaLe a româNiei - Bibliografia Naţională Română seria: Cărţi.Albume.Hărţi seria: Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale : anual seria: Articole din publicaţii periodice. Cultură: lunar seria: Publicaţii seriale: anual seria: Românica: anual seria: Teze de doctorat: semestrial - Aniversări culturale, 2/an - Biblioteconomie: sinteze, metodologii, traduceri , 2/an - Abstracte în bibliologie şi ştiinţa informării, 2/an - Bibliografia cărţilor în curs de apariţie (CIP), 12/an - Revista Bibliotecii Naţionale a României, 2/an - Revista română de istorie a cărţii, 1/an - Revista română de conservare și restaurare a cărții, 1/an Abonamentele la publicaţiile Bibliotecii Naţionale a României se pot face prin Biblioteca Naţională a României , biroul Editorial (telefon 021 314.24.34/1095) Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Blv. Unirii, nr.22, sect. 3, Bucureşti, cod 030833 Tel.021 314.24.34; Fax:021 312.33.81 E-mail: [email protected] Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale 3 CUPRINS COMPACT DISCURI - Listă divizionare .......................................................... -

Voices of Children

VOICES OF CHILDREN SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA, 2017 SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA 01 2017 This report was prepared as per UNICEF Bulgaria assignment. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF. This report should be quoted in any reprint, in whole or in part. VOICES OF CHILDREN Survey of the Opinion of Children and Young People in Bulgaria, 2017 © 2018 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Permission is required to reproduce the text of this publication. Please contact the Communication section of UNICEF in Bulgaria, tel.: +359 2/ 9696 208. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Blvd Dondukov 87, fl oor 2 Sofia 1054, Bulgaria For further information, please visit the UNICEF Bulgaria website at www.unicef.org/bulgaria SURVEY OF THE OPINION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BULGARIA 02 2017 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................2 2. Methodological Note .....................................................................................................................5 3. How happy are Bulgarian children? ............................................................................................10 3.1. Self-Assessment .................................................................................................................12 3.2. Moments when children feel -

Dancing Through the City and Beyond: Lives, Movements and Performances in a Romanian Urban Folk Ensemble

Dancing through the city and beyond: Lives, movements and performances in a Romanian urban folk ensemble Submitted to University College London (UCL) School of Slavonic and East European Studies In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) By Elizabeth Sara Mellish 2013 1 I, Elizabeth Sara Mellish, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the lives, movements and performances of dancers in a Romanian urban folk ensemble from an anthropological perspective. Drawing on an extended period of fieldwork in the Romanian city of Timi şoara, it gives an inside view of participation in organised cultural performances involving a local way of moving, in an area with an on-going interest in local and regional identity. It proposes that twenty- first century regional identities in southeastern Europe and beyond, can be manifested through participation in performances of local dance, music and song and by doing so, it reveals that the experiences of dancers has the potential to uncover deeper understandings of contemporary socio-political changes. This micro-study of collective behaviour, dance knowledge acquisition and performance training of ensemble dancers in Timi şoara enhances the understanding of the culture of dance and dancers within similar ensembles and dance groups in other locations. Through an investigation of the micro aspects of dancers’ lives, both on stage in the front region, and off stage in the back region, it explores connections between local dance performances, their participants, and locality and the city. -

Romania - Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review Th 15 Session of the UPR - Human Rights Council

Romania - Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review th 15 session of the UPR - Human Rights Council Contributed by: El Tera Association Roma Center for Social Intervention and Studies- Romani CRISS Sanse Egale Association Sange Egale pentru Copii si Femei 1 INTRODUCTION Under the universal periodic review, the submitting organizations have used primarily information collected by Romani CRISS, during 2008 until present, since Romania was most recently evaluated under the UPR. Romani CRISS, as well as human rights local monitors’ organizations, are documenting cases in the field cases of violation of human rights of the Roma communities’ members. The current submission will focus on the following areas: right to human dignity; right to life; right not to be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, right not to be discriminated against; freedom of movement and right to leave any country; right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being – with a particular focus on housing and medical care; right to education. The submission will also look at developments since the previous review, particularly normative and institutional framework, for the promotion and protection of human rights. 1. DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE MAY 2008 SESSION Content of recommendation no 6 To continue to respect and promote the human rights of vulnerable groups, including the Roma communities and to continue to take further action to ensure equal enjoyment of human rights by Roma people, as well as to take further appropriate and effective measures to eliminate discrimination against Roma and ensures in particular their access to education, housing, healthcare and employment without discrimination, and gives a follow up to the recommendations of the United Nations human rights bodies in this regard. -

ENGLISH Original: GERMAN R

PC.SHDM.NGO/40/16 26 April 2016 Translation ENGLISH Original: GERMAN R. Possekel Berlin, April 2016 OSCE 14-15 April 2016 Policies and Strategies to Promote Tolerance and Non-Discrimination 1. Will we ever be able to get rid of all prejudices and stereotypes? Certainly not. What can we therefore actually achieve with education, for example? We talk about anti-Semitism, racism, Islamophobia, homophobia and transphobia, gender-based discrimination, antiziganism, intolerance against Christians and Muslims, etc. This necessary separation into specific issues and the communication that it gives rise to creates – without us being able to prevent this – the impression that this is not so much an interconnected problem, but is rather about the problems of individual affected groups: black people, Jews, Sinti and Roma, the LGBT community, Muslims, etc. In spite of this, how can the topic be addressed as a problem that can affect any citizen directly? How can efforts to counter anti-Semitism, for example, help to tackle antiziganism or homophobia? How can efforts to counter Islamophobia, for example, help to tackle anti-Semitism? We need an explicitly “more political” concept of prejudices and/or stereotypes for this. Irrespective of the specific people who suffer such discrimination, the pattern, the fundamental problem, is always the same, namely the fact that individual people are denied their fundamental rights by being assigned to a group whose purported inferiority is established and considered to be legitimate. This is the degrading process, which variously affects Jews, Roma or Muslims, that discounts individuals with their beliefs and actions and reduces them to their membership of a group over which they have no influence. -

Traditional Hungarian Romani/Gypsy Dance and Romanian Electronic Pop-Folk Music in Transylvania

Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, 60 (1), pp. 43–51 (2015) DOI: 10.1556/022.2015.60.1.5 TRADITIONAL HUNGARIAN ROMANI/GYPSY DANCE AND ROMANIAN ELECTRONIC POP-FOLK MUSIC IN TRANSYLVANIA Tamás KORZENSZKY Choreomundus Master Programme – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice and Heritage Veres Pálné u. 21, H-1053 Budapest, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This fi eldwork-based ethnochoreological study focuses on traditional dances of Hungar- ian Romani/Gypsy communities in Transylvania (Romania) practiced to electronic pop-folk music. This kind of musical accompaniment is applied not only to the fashionable Romanian manele, but also to their traditional dances (named csingerálás1, cigányos). Thus Romanian electronic pop-folk music including Romani/Gypsy elements provides the possibility for the survival of Transylvanian Hungarian Romani/ Gypsy dance tradition both at community events and public discoes. The continuity in dance idiom is maintained through changes in musical idiom – a remarkable phenomenon, worthy of further discussion from the point of view of the continuity of cultural tradition. Keywords: csingerálás, pop-folk, Romani/Gypsy, tradition, Transylvania INTRODUCTION This fi eldwork-based ethnochoreological study focuses on traditional dances of a Hungarian Romani/Gypsy2 community at Transylvanian villages (Romania) practiced for Romanian electronic pop-folk music. Besides mahala, manele-style dancing prevailing in Romania in Transylvanian villages, also the traditional Hungarian Romani/Gypsy dance dialect – csingerálás – is practiced (‘fi tted’) for mainstream Romanian pop music, the 1 See ORTUTAY 1977. 2 In this paper, I follow Anca Giurchescu (GIURCHESCU 2011: 1) in using ‘Rom’ as a singular noun, ‘Roms’ as a plural noun, and ‘Romani’ as an adjective. -

20131008170625 20131008 Cliche Panel All Proposals

ANTIZIGANISM CONFERENCE Main seminar: Third session 9:00 -11:00 am Session “Squaring the Circle of protection and empowerment” – 3 papers Chairs & Discussants: Matthew Kott & Timofey Agarin (we will do both together!) On the Transcendence of National Citizenship in the Light of the Case of Roma, an Allegedly Non-territorial Nation” Márton Rövid Central European University The Roma are increasingly seen as a group that challenges the principle of territorial democracy and the Westphalian international order. While diverse in customs, languages, church affiliations, and citizenship, the Roma can also be seen as members of a non-territorial nation. One international non-governmental organization, the International Romani Union, advanced claims for the recognition of the non-territorial Romani nation and advocated a general vision in which people are no longer represented on the basis of state. The manifesto “Declaration of Nation” claims that the Roma have survived for several centuries as distinct individuals and groups with a strong identity without creating a nation-state, so therefore, their example could help humanity find an alternative way to satisfy the need for identity without having to lock it to territorial boundaries. The paper studies theories of post-national citizenship in the light of the case of Roma. What are the empirical preconditions of the transcendence of liberal nationhood? Under what circumstances can claims of post-national citizenship be justified? To what extent do transnational social, religious, and ethnic movements challenge the foundations of the so-called Westphalian international order, in particular the trinity of state-nation-territory? What forms of political participation do they claim? Do transnational nations pose a different challenge to normative political theory than other transnational communities? By studying the case of Roma, the paper relates the literature on diasporas and global civil society to cosmopolitan theories thus offering a new typology of boundary problems.