Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anexe La H.C.G.M.B. Nr. 254 / 2008

NR. FELUL LIMITE DENUMIREA SECTOR CRT. ARTEREI DELA ..... PANA LA ..... 0 1 2 3 4 5 1 Bd. Aerogarii Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti Bd. Ficusului 1 2 Str. Avionului Sos. Pipera Linie CF Constanta 1 3 Bd. Averescu Alex. Maresal Bd. Ion Mihalache Sos. Kiseleff 1 4 Bd. Aviatorilor Pta Victoriei Sos. Nordului 1 5 P-ta Aviatorilor 1 6 Str. Baiculesti Sos. Straulesti Str. Hrisovului 1 7 Bd. Balcescu Nicolae Bd. Regina Elisabeta Str. CA Rosetti 1 8 Str. Baldovin Parcalabul Str. Mircea Vulcanescu Str. Cameliei .(J' 9 Bd. Banu Manta Sos. Nicolae Titulescu Bd. Ion Mihalache /'co 1 ~,..~:~':~~~.~. (;~ 10 Str. Beller Radu It. avo Calea Dorobanti Bd. Mircea Eliade ,i: 1 :"~," ~, ',.." " .., Str. Berzei ,;, 1 t~:~~:;:lf~\~l'~- . ~: 11 Str. Berthelot Henri Mathias, G-ral Calea Victoriei .. ~!- .~:,.-::~ ",", .\ 1.~ 12 P-ta Botescu Haralambie ~ . 13 Str. Berzei Calea Plevnei Calea Grivitei 1 ~; 14 Str. Biharia Bd. Aerogarii Str. Zapada Mieilor 1 15 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti P-ta Presei Libere Str. Elena Vacarescu 1 16 Sos. Bucuresti Targoviste Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos.Odaii 1 17 Bd. Bucurestii Noi Calea Grivitei Sos. Bucurestii Targoviste 1 18 Str. Budisteanu Ion Str. G-ral Berthelot Calea Grivitei 1 19 Str. Buzesti Calea Grivitei P-ta Victoriei 1 20 P-ta Buzesti 1 21 Str. Campineanu Ion Str. Stirbei Voda Bd. Nicolae Balcescu 1 22 Str. Caraiman Calea Grivitei Bd. Ion Mihalache 1 23 Str. Caramfil Nicolae Sos. Nordului Str. Av. AI. Serbanescu 1 24 Bd. Campul Pipera Aleea Privighetorilor 1 25 P-ta Charles de Gaulle -'- 1 26 Sos. Chitilei ,.".ll·!A Bd. Bucurestii Noi Limita administrativa - 1 27 Str. -

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

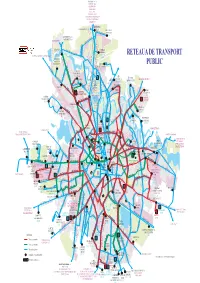

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

Bucharest Booklet

Contact: Website: www.eadsociety.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/EADSociety Twitter (@EADSociety): www.twitter.com/EADSociety Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eadsociety/ Google+: www.google.com/+EADSociety LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/euro-atlantic- diplomacy-society YouTube: www.youtube.com/c/Eadsociety Contents History of Romania ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 What you can visit in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Where to Eat or Drink ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Night life in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Travel in Romania ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....10 Other recommendations …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….11 BUCHAREST, ROMANIA MIDDLE AGES MODERN ERA Unlike plenty other European capitals, Bucharest does not boast of a For several centuries after the reign of Vlad the Impaler, millenniums-long history. The first historical reference to this city under Bucharest, irrespective of its constantly increasing the name of Bucharest dates back to the Middle Ages, in 1459. chiefdom on the political scene of Wallachia, did undergo The story goes, however, that Bucharest was founded several centuries the Ottoman rule (it was a vassal of the Empire), the earlier, by a controversial and rather legendary character named Bucur Russian occupation, as well as short intermittent periods of (from where the name of the city is said to derive). What is certain is the Hapsburg -

LIST of HOSPITALS, CLINICS and PHYSICIANS with PRIVATE PRACTICE in ROMANIA Updated 04/2017

LIST OF HOSPITALS, CLINICS AND PHYSICIANS WITH PRIVATE PRACTICE IN ROMANIA Updated 04/2017 DISCLAIMER: The U.S. Embassy Bucharest, Romania assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by the medical professionals, medical facilities or air ambulance services whose names appear on the following lists. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. Professional credentials and areas of expertise are provided directly by the medical professional, medical facility or air ambulance service. When calling from overseas, please dial the country code for Romania before the telephone number (+4). Please note that 112 is the emergency telephone number that can be dialed free of charge from any telephone or any mobile phone in order to reach emergency services (Ambulances, Fire & Rescue Service and the Police) in Romania as well as other countries of the European Union. We urge you to set up an ICE (In Case of Emergency) contact or note on your mobile phone or other portable electronics (such as Ipods), to enable first responders to get in touch with the person(s) you designated as your emergency contact(s). BUCHAREST Ambulance Services: 112 Private Ambulances SANADOR Ambulance: 021-9699 SOS Ambulance: 021-9761 BIOMEDICA Ambulance: 031-9101 State Hospitals: EMERGENCY HOSPITAL "FLOREASCA" (SPITALUL DE URGENTA "FLOREASCA") Calea Floreasca nr. 8, sector 1, Bucharest 014461 Tel: 021-599-2300 or 021-599-2308, Emergency line: 021-962 Fax: 021-599-2257 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.urgentafloreasca.ro Medical Director: Dr. -

Romania Market Overview Real Estate Highlights H1 2018

Romania Market Overview Real Estate Highlights H1 2018 In Romania ROMANIA MARKET OVERVIEW H1 2018 YoY dynamics of the economy “decelerated from 6.7% in 4Q2017 to 4% YoY in 1Q2018, the slowest pace since 3Q2015. Total stock in Bucharest reached 2.6 million sq m at the end of H1 2018 for class “A & B office buildings. 04 06 10 Romanian Economic Office Investment Overview Market Market 12 14 16 Retail Land Industrial Market Market Market By the end of 2018 approx. 170,000 sq m new retail space are “forecast to be delivered. 18 20 21 Residential Project Property Market Management Taxation 22 Legal Aspects The housing prices in Romania increased “in Q1 2018 by 1.4% compared to Q4 2017. In H1 2018, the modern industrial stock “in Bucharest doubled in comparison with 2015. Contents 2 | KNIGHTFRANK.COM.RO KNIGHTFRANK.COM.RO | 3 ROMANIA MARKET OVERVIEW H1 2018 As regards the supply-side there can be noticed the increase of the primary sector by Romanian Economy 6.7% YoY during January−March. The value added in IT&C also climbed by The convergence 5.4% YoY in 1Q2018. At the same time, the domestic industry advanced by 4.4% YoY, an evolution towards potential supported by the exports’ impulse and by the relaunch of the public investments. Dr. Andrei Radulescu The cyclical component trade/auto- Director Analiza moto repair/transport and warehousing/ Macroeconomica HORECA also rose by 3.7% YoY. On the Banca Transilvania other hand, the construction sector adjusted by 2.1% YoY in 1Q2018. According to the flash estimates of the National Institute of Statistics the Romanian This evolution confirms the maturity phase At the same time, the private consumption with the exports during 2018−2020: annual economy slightly accelerated in 2Q2018 of the post-crisis cycle, in a context of (the main component of the GDP) climbed average paces of 8.6% vs. -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Bucharest Meet: Iuliu Maniu and Vasile Milea

#welcome @ CAMPUS 6 swipe page to begin Homepage #theagenda 1.0 Futureproof 2.0 Location & Amenities 3.0 Site Plan 4.0 Placemaking & Social Impact 5.0 Interior & Innovations 6.0 Green Features 7.0 About Us 8.0 Contact 1.0 Futureproof 1 Architecture 2 Placemaking 3 Art We stand by our promise to deliver high-class offices, combining the best design practices, the principles of sustainable development and technological innovation. We offer our customers solutions that support their present and future needs. 1 Products 1 Wellbeing 2 Connected by Skanska 2 Biodiversity 3 BIM 3 Certification 1.0 Futureproof We are constantly looking for new materials and technological solutions so that our buildings are ready for the challenges of the future. INNOVATIONS What does it mean to us? Trends come and go and style evolves. Futureproof is a symbol that defines the focus areas that make Skanska a trustworthy partner. Our investments are determined by functionality, low maintenance costs and minimal impact on the environment. Located in the best spots in the city, they are highly valuable assets on the office buildings market. Sustainable development is in our company’s DNA, therefore we design and construct our buildings aiming to benefit the society and respect the environment. SUSTAINABILITY Based on our Scandinavian roots and cooperation with top-notch architects, we provide timeless and functional design of our buildings. DESIGN 2.0 Location & Amenities #welcome We designed Campus 6 with one goal: to change Campus the way people mix life and work. 6.1 Q3 2018 Campus sqm 6.2 81 000 GLA in 4 phases Q4 2019 1 000 parking places floors of office spaces Campus 10 6.3 Q3 2021 Campus 6.4 Q4 2022 POLITEHNICA UNIVERSITY Campus 6.3 Campus 6.4 Campus 6.2 Campus 6.1 Iuliu Maniu Ave. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat. -

Pipera Neighborhood

www.ssoar.info Pipera Neighborhood - Voluntari City (Romania): problems regarding inconsistency between the residential dynamic and the street network evolution between 2002 and 2011 COSTACHE Romulus; TUDOSE Ionuț Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: COSTACHE Romulus, & TUDOSE Ionuț (2012). Pipera Neighborhood - Voluntari City (Romania): problems regarding inconsistency between the residential dynamic and the street network evolution between 2002 and 2011. Cinq Continents, 2(6), 201-215. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-325228 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Volume 2 / Numéro 6 Hivér 2012 ISSN: 2247 - 2290 p. 201-215 PIPERA NEIGHBOURHOOD - VOLUNTARI CITY. PROBLEMS REGARDING INCONSISTENCY BETWEEN THE RESIDENTIAL DYNAMIC AND THE STREET NETWORK EVOLUTION BETWEEN 2002 AND 2011 Romulus COSTACHE Ionuț TUDOSE Master Std. Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest [email protected] Contents: 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Suzuki ,Kia,Multimarca

Reprezentanta pentru LOCALITATE JUDET ADRESA Denumire unitate service marca BUCURESTI B sos Alexandriei nr 138 sect 5 A&M SERVICES 2010 MULTIBRAND BUCURESTI B bd Timisoara nr 161 sector 6 AEF AUTOMOBILE MULTIBRAND Bdul Theodor Pallady nr 287 BUCURESTI B sector 3 BUCURESTI ANDRE S FAST SERVICE MULTIBRAND STR INTRAREA CARAVANEI NR 9 BUCURESTI B SECTOR 6 AUTO COM S.T MULTIBRAND Str Fabrica de Chibrituri nr 24-26 s BUCURESTI B 4 AUTO CONSULTING C&G MULTIBRAND bd Energeticienilor nr 13-15 sector BUCURESTI B 3 BUCURESTI AUTO FIRST CLASS PROFESSIONAL MULTIBRAND SOS GARII CATELU NR 180 190 BUCURESTI B SECTOR 3 AUTO LEADER EXPIM MULTIBRAND Str C-tin Dobrogeanu Gherea nr BUCURESTI B 109 sector 1 AUTO LUCK COM MULTIBRAND SOS PANTELIMON NR 450 BUCURESTI B SECTOR 2 AUTO MARCU S GRUP DACIA ,RENAULT SPLAIUL UNIRII NR 311 SECTOR DACIA , RENAULT, BUCURESTI B 3 AUTOCOBALCESCU NISSAN ,BMW SOS COLENTINA NR 459 B- FIAT , ALFA ROMEO , BUCURESTI B DUL IULIU MANIU 187 AUTOITALIA JEEP , LANCIA BUCURESTI B SPLAIUL UNIRII NR 166 A SECT 4 AUTOKLASS CENTER SUD Mercedes-Benz , HONDA SOS BUCURESTI PLOIESTI NR 53 BMW , LAND ROVER , BUCURESTI B A SECTOR1013685 AUTOMOBILE BAVARIA MINI SOS BUCURESTI PLOIESTI NR 42- BUCURESTI B 44 SECTOR 1 AUTOMOTIVE TRADING SERVICE FORD Str VALEA LUNGA NR 30 SECTOR BUCURESTI B 6 AUTOMOTIVE UNIK SOLUTIONS MULTIBRAND CALEA GIULESTI NR 126 SECTOR SUZUKI BUCURESTI B 6 060262 AUTONET SRL ,KIA,MULTIMARCA str Drumul Jilavei nr 12 sector 4 BUCURESTI B BUCURESTI AUTOTEHNIC SERVICE MULTIBRAND BUCURESTI B str Reconstructiei nr 2 sector 3 AUTOWAB MULTIBRAND BUCURESTI B Bd PRECIZIEI nr 13G SECTOR 6 BAMAV AUTOSERVICE MULTIBRAND SOS VIRTUTII NR 55-57 SECTOR BUCURESTI B 5 BDT FORD , MAZDA BUCURESTI B INTR BINELUI nr 1 A sector 4 BEST M&R PRO CARS MULTIBRAND B- DUL IULIU MANIU NR 291 SKODA , SEAT , VW , BUCURESTI B SECTOR 6 BRADY TRADE AUDI BUCURESTI B str HALMEU nr 2 SECTOR 2 CARMADA AUTO MULTIBRAND CALEA GRIVITEI NR 143 SECTOR BUCURESTI B 1 CARPATI MOTOR HONDA BUCURESTI B SOS OLTENITEI NR 229 SECT 4 CARS INV.